The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 30 (2024) No. 1

Organ Music per l’elevatione and the Council of Trent in Seventeenth-Century Italy: Contexts, Style, and Performance Practices as a Musical Representation of the Nature of the Mass

Federico Terzi*

Abstract

Seventeenth-century Italian organ music for the Elevation in the Catholic Mass may be interpreted as an indirect musical consequence of the decree concerning the nature of the Mass issued at the twenty-second session of the Council of Trent (17 September 1562). The Council decreed the sacrificial nature of the Mass to be fully manifested at Elevation. Using slow tempo and an emphasis on chromaticism, dissonance, and suspensions, among other traits, organ pieces for Elevation create a sonic atmosphere that supports the central mystery of the Mass. This study takes into account the context of the conciliar statements; it considers liturgical books and theoretical and pedagogical treatises; it identifies organ pieces for Elevation found in manuscript and printed collections; and it analyzes genres (such as the “toccata per l’elevatione”), styles, musical models, and performance practices to demonstrate a clear connection between this music and the reenactment of Christ’s sacrifice.

2. The Tridentine Statements about the Catholic Mass: Sacrificial Nature and Devotion to the Mystery

4. Organ Music for the Elevation: Forms, Style, and Models

5. Performance Practices: Prescriptions in Treatises and Annotations in the Scores

1. Introduction

1.1 In the traditional Latin Mass, organ music for the Elevation was performed at the moments of consecration and elevation of the Host and the Chalice. The following article, focusing on seventeenth-century Italy, interprets this type of organ piece in relation to the chapters about “the sacrifice of the Mass” issued at the twenty-second session of the Council of Trent (1545–63). It is a central aim of this essay to demonstrate how the musical tropes of Elevation organ music and the prescriptions for the genre made by theorists and composers in that period are meant to express the sacrificial and mysterious nature of the Holy Eucharist asserted by the Council.

1.2 The study is divided into five sections as follows: the conciliar statements about the Mass; the liturgical context in which Elevation organ pieces were performed; the musical forms, style, and models characterizing this music; prescriptions and annotations in Italian sources; and conclusions.[1]

2. The Tridentine Statements about the Catholic Mass: Sacrificial Nature and Devotion to the Mystery

2.1 After a series of attempts, the Council of Trent finally opened on 13 December 1545, the Gaudete Sunday of that year.[2] The council fathers began to deal with the importance of the Mass almost immediately, as early as the first months of 1547, although the decrees were not finalized until the twenty-second session (17 September 1562). At this session, the Council drew on elements from both Scripture and Catholic tradition and reaffirmed earlier Church teaching that the Mass is a re-presentation of Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross. At Mass, the same Christ who has already been immolated is made present under the species of bread and wine and is immolated another time in a bloodless manner. This “true and proper” sacrifice is not additional to the sacrifice at Calvary but consists of one and the same oblation offered to God. Mass is, therefore, Christ’s self-offering established by him with the Last Supper to prolong the graces received from the sacrifice on the Cross.[3]

2.2 In this regard, a couple of interlinked factors are relevant: the mediation of the priest, at whose hands Christ’s sacrifice is made present on the altar, and the real presence of Christ ensured by means of the transubstantiation of the Host and the Chalice at the moment of consecration.

2.3 The former aspect was discussed at the twenty-second session (and issued in chapter one): during the Last Supper, Christ instituted the Mass and appointed the apostles as his successors as priests of the New Covenant.[4] In effect, the Council restated the “singular status of the priest,” connecting priests to Christ through the apostles and the apostolic succession, identifying the priesthood as a distinct order in the Church. In the conciliar perspective, the figure of the priest as a mediator is therefore an essential one and a prerequisite for the validity and efficacy of the Mass.[5]

2.4 As regards the transubstantiation of the Host and the Chalice, it had already been discussed at the thirteenth session (11 October 1551), which made the point about Christ’s presence in the Eucharistic Sacrament as well.[6] The decree on the Eucharist issued on that occasion is based on the teachings of the Fourth Lateran Council,[7] and consists of eight chapters and eleven canons. In particular, the fourth chapter deals with the transubstantiation and real presence. It states that, by means of the consecration prayers formulated by the priest before the Elevation, both bread and wine turn into the body and blood of Christ.[8] As a result of these two factors, Christ is sacramentally present during Mass, providing the celebration with the same “saving power” of his sacrifice on the Cross for the living and the dead. Notably, as has been remarked,[9] the relation between the immolation on the Cross and the Mass is an essential one and develops precisely when bread and wine are consecrated before the Elevation.

2.5 As early as the beginning of the thirteenth century, the Elevation was perceived as the most important moment of the Eucharistic celebration, the only one considered compulsory to attend.[10] As recalled by the introduction to the “Decree concerning the things to be observed and avoided in the celebration of the Mass” (twenty-second session), the Elevation incorporates the holiest and the most divine action a faithful can accomplish, the “tremendous mystery” (tremendum mysterium) by which the life-giving Host is immolated as a sacrifice to God for the salvation of all.[11] Other connected mysteries are included in this: in addition to the transubstantiation and the real presence just mentioned, the seventh chapter of the “Doctrine and canons of the Holiest sacrifice of the Mass,” for example, refers to the mystery of water and wine mixed in the Chalice and symbolizing the union between the Church and Christ himself.[12] For these reasons, the Council stresses the attitudes of worship, contemplation, and devotion with which the Eucharistic celebration must be approached: in the second, in the fourth, and in the fifth chapter of the same “Doctrine and canons of the Holiest sacrifice of the Mass,” references are made to “awe and reverence” (metu et reverentia), to “holiness and devotion” (sanctitatem ac pietatem), and to the signs of “religious sentiment and devotion” (religionis ac pietatis signa).[13] Of course, as the Elevation is the climax of the Mass from the perspective of the faithful, it follows that these expressions of devotion must be manifested in particular at this point of the celebration.

2.6 Given this framework, the Council outlined the nature of the Mass as sacrificial and mysterious. It consists, in fact, in the reenactment of Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross to which the faithful must show the greatest devotion, awe, and worship. Both these facets are displayed at the Elevation when, thanks to the real presence of Christ granted by the transubstantiation and enacted by the priest, the Sacrifice of Calvary is re-offered to God.

3. Liturgical Contexts

3.1 In Italy, from the late sixteenth century onwards, organists were principally required to play during Mass and vespers, generally fulfilling four tasks: to accompany instrumentalists and singers in the performance of polyphony; to fill particular liturgical moments with music (processions, for example); to take part in the alternatim performance by playing short versets between the verses sung by the choir; and to replace the singing of some liturgical texts with free organ works or improvisations (not always based on a cantus firmus), such as the Introit, the Gradual, the Offertory, the Elevation, and the Communion, or at the position of post-psalm antiphons during the office.[14] In particular, Elevation organ music normally consists of free organ works, performed after the Sanctus, replacing the Benedictus, and continuing up to the moment of the elevation of the consecrated bread and wine.[15]

3.2 Along with some examples of polyphonic masses that do not include the Benedictus,[16] several collections of organ versets for alternatim performance confirm this framework and the fact that the Benedictus was not commonly sung by the choir but was assigned to the organ. In the Annuale (1645) by Giovanni Battista Fasolo, for instance, one finds not only that two Elevation pieces are explicitly titled “Benedictus et elevatio,”[17] but also that one of them is entitled “Benedictus et elevatio simul,” suggesting that it was conceived for the Benedictus and the Elevation “at the same time” (simul). As is the case with the Annuale, other Italian printed collections of organ music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries do not generally provide more than two versets for the Sanctus, suggesting that the Benedictus was replaced with an organ piece. Although Matteo Asola’s Canto fermo sopra Messe, hinni et altre cose ecclesiastiche (1592) constitutes an exception in this respect, the organ masses by Girolamo Cavazzoni (1543–49), Claudio Merulo (1568), and Andrea Gabrieli (before 1585), as well as those in Bernardino Bottazzi’s Choro et organo (1614), Giovanni Salvatore’s Ricercari a 4 voci, canzoni francesi, toccate e versi per rispondere nelle messe con l’organo al choro Libro Primo (1641), and Antonio Croci’s Frutti musicali (1642), each contain two Sanctus pieces;[18] furthermore, in his L’organo suonarino (1611), Adriano Banchieri recommends that the organist play “twice and briefly” (“due volte et brevemente”) at the Sanctus.[19]

3.3 For the sake of completeness, it must be acknowledged that vocal music could be performed at the Elevation as well—motets for small vocal ensemble, eventually with organ bass, based on texts regarding the presence of Christ in the Host. This practice is attested, moreover, by Lorenzo Ratti’s Sacræ modulationes (1628) and also on a smaller scale by Amante Franzoni’s Apparato musicale (1613), by Carlo Milanuzzi’s Armonia sacra (1622), by the Avvertimenti in Ignazio Donati’s Salmi boscherecci (1623), and by other sources such as I-SGc Ms. F.S.M. 58, which contains at fols. 5r–6r a motet for the Offertory or Elevation (O dulcissime Jesu).[20] In particular, high relevance is assumed for Agostino Agazzari’s Eucaristicum melos (1625), a collection of Sacramental motets for Quarantore (Forty Hours Devotion) and, by extension, Elevation.[21] Furthermore, it was common practice to use vocal settings of Eucharistic prayers at the Elevation of Requiem Masses when the use of the solo organ was formally forbidden.[22]

4. Organ Music for the Elevation: Forms, Style, and Models

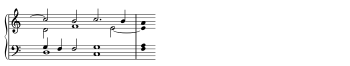

4.1 Table 1 and Table 2 list all seventeenth-century Italian organ music for Elevation found during this research, in printed and manuscript sources respectively (with sigla provided for manuscripts cited in the text).[23] As shown there, different musical forms could be adopted for organ pieces conceived for this moment of the liturgy. Together with the pieces generically entitled “Elevazione,” “Elevatione,” or “Elevatio,” the principal musical genre appears to be the “toccata per l’elevatione” (Elevation toccata), a free organ piece that, as Alexander Silbiger has remarked, has “no exact equivalents in other musical repertories.”[24] Nevertheless, a “Sonata” is found in Banchieri’s Appendice all’organo suonarino[25] and another in I-Rv Ms. Z. 121,[26] and a “Toccata in eco” (“ecco” in the source) in I-COd Ms. AA21–8–40.[27] It also happens that the pieces entitled “Toccata” or “Elevatione” are actually characterized by a contrapuntal style of writing like that of a ricercar: see Banchieri’s Elevation toccatas in L’organo suonarino and the “All’elevatione” at fols. 19r–20r in I-SGc Ms. F.S.M. 58 (Exx. 1, 2, and 3).[28]

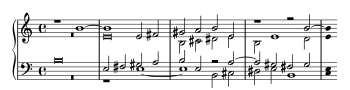

4.2 Among the Elevation organ pieces composed in Italy during the seventeenth century, scholars such as Luigi Ferdinando Tagliavini have already pointed out the prominence of Girolamo Frescobaldi’s Elevation toccatas contained in the three organ masses (Messa della Domenica, Messa delli apostoli, and Messa della Madonna) of the Fiori musicali (Venice: Alessandro Vincenti, 1635).[29] These three toccatas present many of the characteristics constituting the typical musical style of Italian organ works for Elevation: based on a “melancholic” mode, the third one,[30] they are generally characterized by descending imitative themes (Exx. 4, 5, and 6), widespread presence of chromaticism and dissonances (Exx. 6 and 7), suspensions (Exx. 8a, 8b, and 9), expressive figuration typical of that representing weeping and sighing in contemporaneous vocal monody (Ex. 10), and slow pacing (note the “adagio” indications for the toccatas in the Messa della Domenica and the Messa della Madonna).[31]

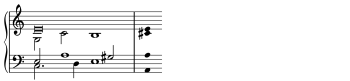

4.3 These same characteristics, already present in the two Elevation toccatas in the first edition of Frescobaldi’s Secondo Libro di Toccate (Rome: Nicolò Borbone, 1627), are generally found in Elevation organ works by other composers.[32] For example, the three pieces in Fasolo’s Annuale are provided with a precise slow tempo indication: “very slow, stressing the dissonances” (“largo assai facendo godere le ligature et durezze”) as regards the Missa in Dominicis diebus;[33] “it will be played very slowly to stress the dissonances” (“si suonera assai largo acciò si godano meglio le ligature”) for the Missæ in duplicibus diebus;[34] “solemn, with very slow pacing” (“gravis ad tempus maioris perfectionis”) in the Missæ beatæ Mariæ virginis.[35] Otherwise, as in the case of Frescobaldi’s “Toccata per le levatione” in the Messa della Madonna (Ex. 10) and Toccata Quarta of the Secondo Libro di Toccate (Ex. 11), Gregorio Strozzi’s Elevation toccata from Capricci da sonare cembali et organi (1687) also presents expressive figuration representing vocal sighs and mournful affetti (Ex. 12).[36] The same figures are employed in the second Elevation toccata in the “Libro Secondo” (1649) by Johann Jakob Froberger (Ex. 13),[37] not preserved in an Italian source but composed following the model of Frescobaldi’s Elevation toccatas in his Secondo Libro di Toccate.

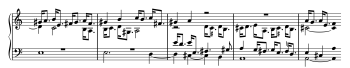

4.4 Finally, chromaticism, dissonances, suspensions, and expressive intervals characterize not only these two Elevation works by Froberger and Strozzi (Exx. 14 and 15), but also, for example, those by Fasolo (Exx. 16a and 16b), as well as the Elevatione attributed to Frescobaldi in D-B Ms. Landsberg 122 (Ex. 17), and the “Sonata grave col principale alla levatione” in the Appendice all’organo suonarino by Banchieri (Ex. 18).

4.5 Three different models dating from the end of the sixteenth century and the beginning of the seventeenth can be identified in Italy for the musical style of these organ pieces: madrigals, sacred vocal music, and certain keyboard works of the Neapolitan school.

4.6 Starting in the late sixteenth century, chromaticism, suspensions, dissonances, false relations, audacious harmonic progressions, and augmented or diminished intervals were often associated with poetic texts about death, anguish, solitude, mystery, and melancholy. See for instance the opening of the famous madrigal Solo e pensoso by Luca Marenzio (1599), in which the highly chromatic canto line is associated with the solitude expressed in the sonnet by Francesco Petrarca (Ex. 19). Another case in point is Moro, lasso, al mio duolo by Gesualdo da Venosa (1611), in which generally highly chromatic chordal writing, typical of Gesualdo, underlines the sections of the text about death and creates a strong contrast with those referring to life (Ex. 20).[38]

4.7 The same musical tropes are employed in sacred vocal music as well: specifically, in Passion music, for the purpose of recreating Christ’s sufferings; in other cases, for the purpose of conveying a sense of awe, reverence, and devotion. For example, as regards the first case, in Marco Antonio Ingegneri’s Plange quasi virgo (“Responsorium III, Sabbato Sancto” of the Responsoria Hebdomadæ Sanctae, 1588), the composer not only makes use of what would later be called the “chromatic third relation,” but he also employs an augmented chord (Ex. 21). A similar musical language also involved monody—for example, at the very beginning of the Lamentationes Hieremiae Prophetae by Emilio de’ Cavalieri (around 1590; Ex. 22). In the first section of Giovanni Gabrieli’s O magnum mysterium, instead, the chromatic alternation between B-flat and B-natural creates a sort of mystical effect, a transcendent atmosphere that is appropriate to express the mystery the text refers to (Ex. 23).

4.8 At the beginning of the seventeenth century, some keyboard composers from Naples began to transfer this musical style to keyboard instruments. As regards this point, once again scholars have focused particularly on Frescobaldi’s toccatas, investigating the relationship between them and keyboard works by composers such as Giovanni De Macque, Ascanio Mayone, and Giovanni Maria Trabaci.[39] Specifically, providing clear musical examples, Roland Jackson remarked on some connections between De Macque’s “Capriccio sopra re mi fa sol,” Trabaci’s “Consonanze stravaganti,” and the beginning of Frescobaldi’s Toccata Quarta in the Secondo Libro di Toccate. Furthermore, the same scholar identifies common chromatic patterns in Frescobaldi’s “Toccata chromatica” (Messa della Domenica in the Fiori musicali) and Trabaci’s “Durezze et ligature.”[40] In effect, the typical characteristics of the musical style of the organ music for the Elevation were already employed by these Neapolitan composers in keyboard works entitled “Stravaganze,” “Consonanze stravaganti,” “Durezze et ligature,” or merely “Ligature” or “Durezze.” In particular, De Macque composed two “Stravaganze,” a “Consonanze stravaganti,” and a “Durezze et ligature,”[41] and Trabaci a “Durezze et ligature” (1603; Ex. 24), a “Consonanze stravaganti” (1603), and a Toccata Seconda with “Ligature per l’arpa” (1615);[42] in addition, several “durezze” sections are found in Mayone’s Toccata Quarta and Toccata Quinta, both composed for the “cembalo chromatico” (1609).[43] The titles of these compositions are sufficient to evoke the features of these pieces: “exaggerated chromaticism,” “harmonic boldness accentuated by block chordal texture,” “dissonances and suspensions.”[44]

4.9 However, unlike the Elevation pieces, the stravaganze of the Neapolitan school are not intended for liturgical purposes: as in the case of Frescobaldi’s Toccata Ottava “di durezze et ligature” (Secondo Libro di Toccate), they are remarkable compositions not even explicitly aimed to be performed on the organ. Nevertheless, several Italian organ works for the Elevation could well be considered as a liturgical reinterpretation of these keyboards works. As regards the style of writing, organ pieces like those by Fasolo (Exx. 16a and 16b), for example, are not much different from the “Durezze et ligature” by Trabaci (Ex. 24) or by other Neapolitan composers. In Fasolo’s and others’ Elevation works, however, dissonances, suspensions, and chromaticism are aimed to evoke Christ’s suffering on the Cross: as we have seen, according to the Tridentine decrees, at Elevation the sacrificial nature of the Mass is fully manifested, and the reenactment of Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross takes place. For this reason, the style of the organ music performed at Elevation must provide a sonic atmosphere able to recall, even recreate, that mystery: it is not by chance, therefore, that the “durezze” recurring in the Neapolitan keyboard works, as well as many of the musical tropes used in sacred and profane vocal music relating to Passion, death, and mystery, were deemed suitable for the organ repertory for Elevation.

5. Performance Practices: Prescriptions in Treatises and Annotations in the Scores

5.1 At this point, the relationship between the Tridentine decrees on the sacrificial nature of the Mass and the organ music conceived for Elevation may appear rather clear. However, analysis of the genres, styles, and stylistic models of these organ pieces gives only an implicit confirmation of this connection; it becomes more explicit in light of several liturgical books and theoretical and pedagogical treatises produced in Italy in the decades after the Council.

5.2 Although rather generic, the first official prescription for organ music for the Elevation is found in the Cærimoniale Episcoporum (1600), the official post-Tridentine manual regarding liturgy. In this text a chapter is devoted to the organ, organist, singers, and other musicians, and to the rules they must follow during the divine services.[45] In particular, the Cærimoniale not only specifies the liturgical occasions on which the organ must be used, but also describes when to use the instrument during Mass. Nevertheless, the Elevation is the only liturgical moment for which a description of the most appropriate music is provided: the organ must be played “with solemn and sweet sound” (“graviori et dulciori sono”) to create a contemplative atmosphere suitable for the most mysterious of all liturgical moments.

5.3 From the Cærimoniale this general prescription passed to music treatises. In the “Ordered Table for Novice Organists” (“Tabella ordinata per gli organisti principianti”) presented in the 1605 edition of his L’organo suonarino, Adriano Banchieri explains that at the Elevation one must play slowly and quietly and that the music performed must “excite to devotion” (“Poi si suona alla Levatione, ma piano, et cosa grave che muovi alla devotione”).[46] Something similar can be read in a second text by Banchieri, the Conclusioni sul suono dell’organo (1609), chapter nine (“Nona conclusione”): “At the Elevation one must play slowly, expressing devotion” (“suonasi alla levatione con gravità che rendi devotione”).[47]

5.4 Furthermore, the Cærimoniale’s remarks were interpreted by composers as performance practice suggestions or as organ stop indications, aimed at providing organ music for the Elevation with the required “solemn and sweet sound.” Evidence for such interpretations is found in composers’ advice to performers included in the prefaces to scores or in the scores themselves. Since no specific indications about Elevation toccatas are present in Frescobaldi’s suggestions “to the readers,” one might turn to the preface of Fasolo’s Annuale in which, firstly, he recommends playing at the Elevation as slowly as possible: “The Elevation must be played very slowly” (“la elevatione vuol essere gravissima”). Secondly, in his opinion, the organist must exaggerate the duration of the dissonances: “[Organists] should pay no attention to whether the notes are white or black; they should emphasize the suspensions, holding the dissonances longer than the notated beat” (“non guardino che le figure siano o bianche o negre ma faccino cadere le ligature, sostenendole alquanto più della sua misura”).[48] These two remarks are reiterated in the scores of the three Elevation pieces, where Fasolo inserts the quoted indications about tempo and dissonances. It is evident that the two factors underlined by Fasolo (a very slow tempo and the emphasis on dissonances) combine to create musically, on the one hand, the mysterious atmosphere demanded by the Cærimoniale and evoked by the Tridentine decrees, and, on the other, the sufferings of the Cross.

5.5 Another indication found in a score of an organ piece for Elevation is the “accentando” markings in Strozzi’s Toccata per l’elevatione (Ex. 12). These indications accompany the same dotted-rhythm figurations used in Elevation toccatas by Frescobaldi and Froberger (Exx. 10, 11, and 13) and were pointed out by Barton Hudson in his 1967 article on Strozzi’s Capricci.[49] Hudson, stressing the rarity of these “verbal directions,” supposes that the composer was probably suggesting to the organist “a very pointed rhythmic interpretation.”[50] In addition to this speculation, it should be noted that Strozzi, with the world “accentando,” is also referring to a performance practice typical of vocal monody in the seventeenth century. Focusing especially on the violin, Constance Frei has shown that in Italy solo instrumental music of the first decades of seventeenth century was strongly influenced by vocal performance practice, as attested by a series of stylistic peculiarities in works by Biagio Marini (1594–1663) and others.[51] As Rebecca Cypess indicates, theorists and composers of this period were convinced of the communicative power of the violin, a musical instrument considered particularly capable of imitating the human voice.[52] Vocal music came to influence keyboard music as well, as demonstrated by Frescobaldi’s prefaces to his books of toccatas, in which the composer underlines the relation between the performance of these compositions and that of the contemporary madrigal. As the research of Étienne Darbellay, Francesco Tasini, and Luigi Ferdinando Tagliavini has detailed, the interpreter is invited to move the affetti of the listener (not surprisingly defined “affetti cantabili” by Frescobaldi) by means of a constant elasticity in the pulsation of the beat, in order to give the work a sense of variety, spontaneity, and contrast.[53] In the case of Strozzi, however, this concept of variety is not applied on a metrical level, but on a melodic one. In fact, as vocal treatises already prescribed at the end of sixteenth century,[54] to add beauty and interest to the musical discourse, the singing line should be performed alternating a long note with a shorter one or vice versa: these variations of the natural accentuation of the musical discourse, more improvised by performers than written down by composers, were called “accenti.”[55] As regards instrumental music, the prescription of this practice was intended to better convey the affetti by trying to imitate the metrical flexibility of human singing and speech. Therefore, with his “accentando” indication, Strozzi is probably referring to this vocal practice—that is, trying to evoke mournful human singing in the playing of the organ during the reenactment at Elevation of Christ’s dolorous sacrifice.

5.6 As for the organ stop indications, the first source deserving attention is Costanzo Antegnati’s Arte organica (1608).[56] Concerning the Elevation, Antegnati states that he usually played using the “principale solo” at this liturgical moment, as this stop is a very sweet one (“delicatissimo”), also well-suited to accompanying a small number of voices singing motets. Additionally, to create an even sweeter atmosphere, the principale can be used with the tremulant stop (“tremolante”) but while playing slowly and without diminutions (“adaggio et senza diminuire”). In the same way, one must play using the combination “principale” and “fiffaro”: this last stop, also known as “registro de voci humane,” or simply “voce umana,” consists of a rank of pipes slightly mistuned to the principale, giving the organ sound a very mystical effect.[57] In this case, the organist must play slowly and as smoothly as possible (“adaggio con movimenti tardi et legato più che si può”). One year after Antegnati’s publication, Girolamo Diruta deals indirectly with organ stops at Elevation, in the second part of his organ manual Il Transilvano (1609). Diruta’s prescriptions for organ registration depend on the ecclesiastical modes as each mode naturally evokes a specific musical atmosphere to which the organ stops must be adapted. With regard to the modes suitable for the Elevation, like Antegnati, Diruta requires the organist to play using the “principale solo” with tremulant (“principale solo con il tremolo”) for the second and fourth modes or “some flute stop” (“qualche registro del flauto”) for the fourth mode. The flauto must be used to obtain an eight-foot pitch (“nelle sue corde naturali” or “nelli suoi tasti naturali”) conveying a sad mood (“con la modulatione mesta”).[58]

5.7 Furthermore, as regards the relation between Elevation organ music and Tridentine decrees, it is of great importance that Diruta explicitly connects the organ music performed at the Elevation to the reenactment of Christ’s sacrifice. Addressing organists directly, in fact, he recommends the second and fourth modes as the most appropriate for music intended for this moment of the liturgy because they are associated with melancholy and a sense of sadness and pain. These two modes, he writes, must be used at the Elevation to imitate in the organ playing “the hard and bitter torments of the Passion” (“imitando con il sonare li duri et aspri tormenti della Passione”).[59] This assertion by Diruta directly associates Christ’s Passion with the features of the organ music considered suitable for Elevation. That association represents the key to understanding the theological implications expressed by this particular typology of liturgical music.[60] In this passage of the Transilvano, Diruta, a pupil of Zarlino—foregrounding the seventeenth-century discussion of the ethos of modes[61]— provides the clearest means to interpret all the material concerning organ music for the Elevation analyzed in this research: its musical style, the theorical prescriptions about it, and its relation with the Tridentine decrees about the nature of the Mass.

6. Conclusions

6.1 As Craig A. Monson has demonstrated in his seminal article about the Council of Trent, the conciliar stipulations about church music are much less “than many music historians have commonly suggested.”[62] As decreed during the twenty-fourth session (11 November 1563), the majority of decisions to reform church music would continue to be taken at a local level, as had long been the case; and despite an interest in music in their preliminary deliberations, the Council members did not in the end make much of that commentary official: the well-known decree prohibiting lascivious music in church, issued at the twenty-second session, was in fact the only official pronouncement concerning music.[63] However, as Paolo Prodi suggests, it seems possible to detect some indirect musical products of the Tridentine resolutions, originating from decrees regarding subjects other than music.[64] As regards seventeenth-century Italy, organ music for the Elevation can be deemed another of these indirect musical products. Considering its musical language alongside the prescriptions of treatises and liturgical books, we should see this music as a consequence of the Tridentine decrees on the theology and nature of the Mass, that is, of the sacramental and mysterious re-presentation of Christ’s sacrifice at Calvary. As taught by the Tridentine Catechism (first edition: 1566), faith was conceived by hearing (“Fides ex auditu concipiatur”).[65] For this reason, in view of the centrality of Elevation at Mass, no other type of liturgical organ music is so intimately related to the liturgy as organ music for the Elevation. Not so different from post-Tridentine preaching encouraging the faithful to penetrate sacred mysteries through an emotional involvement,[66] the organ pieces performed at the Elevation provided a sonic experience aimed to excite the spirit to devotion and to move the senses towards a physical and spiritual understanding of the Mass as a sacrifice.[67]

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Stewart Carter, Jeffrey Kurtzman, and Alexander Silbiger for reading earlier versions of this work. I am particularly indebted to Thomas Neal for his comments and his linguistic revision; to Mattia Marelli for his help with musical examples; to the anonymous JSCM reviewers for their helpful suggestions; to Lois Rosow for her punctilious editorial labor limæ on my text. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Maria Elena, for her endless daily support. The article is dedicated to the loving memory of my grandmother Andreina (1940–2023) who taught me a lot about Eucharist devotion.

Examples

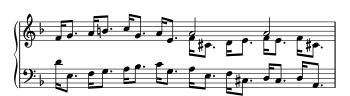

Ex. 1. Adriano Banchieri, “Prima Toccata del terzo tono autentico alla levatione del Santissimo Sacramento,” mm. 11–17, in Adriano Banchieri, L’organo suonarino (1611)

Ex. 2. Banchieri, “Seconda Toccata del quinto tono plagale alla levatione del Santissimo Sacramento,” mm. 1–4, in Banchieri, L’organo suonarino

Ex. 3. Anonymous, “All’elevatione,” mm. 1–10. San Gimignano, Biblioteca Comunale, Ms. F.S.M. 58.

Ex. 4. Girolamo Frescobaldi, “Tocata per le levatione” (Messa delli apostoli), mm. 24–28, in Frescobaldi, Fiori musicali (1635)

Ex. 5. Frescobaldi, “Tocata per le levatione” (Messa delli apostoli), mm. 14–21, in Frescobaldi, Fiori musicali

Ex. 6. Frescobaldi, “Toccata cromaticha per le levatione” (Messa della Domenica), mm. 7–15, in Frescobaldi, Fiori musicali

Ex. 7. Frescobaldi, “Tocata per le levatione” (Messa delli apostoli), mm. 1–5, in Frescobaldi, Fiori musicali

Ex. 8a. Frescobaldi, “Toccata cromaticha per le levatione” (Messa della Domenica), m. 6, in Frescobaldi, Fiori musicali

Ex. 8b. Frescobaldi, “Toccata cromaticha per le levatione” (Messa della Domenica), m. 20, in Frescobaldi, Fiori musicali

Ex. 9. Frescobaldi, “Tocata per le levatione” (Messa degli apostoli), mm. 3–5, in Frescobaldi, Fiori musicali

Ex. 10. Frescobaldi, “Tocata per le levatione” (Messa della Madonna), mm. 18–22, in Frescobaldi, Fiori musicali

Ex. 11. Frescobaldi, “Toccata Quarta per l’organo da sonarsi alla levatione,” mm. 46–52, in Frescobaldi, Secondo Libro di Toccate (1637)

Ex. 12. Gregorio Strozzi, “Toccata Quarta per l’elevatione,” mm. 32–43, in Strozzi, Capricci da sonare cembali et organi (1687)

Ex. 13. Johann Jakob Froberger, “Toccata da sonarsi alla levatione,” m. 16, in Froberger, “Libro Secondo.” Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Mus. Hs. 18706 (1649).

Ex. 14. Froberger, “Toccata da sonarsi alla levatione,” mm. 11–13, in Froberger, “Libro Secondo”

Ex. 15. Strozzi, “Toccata Quarta per l’elevatione,” mm. 19–24, in Strozzi, Capricci

Ex. 16a. Giovanni Battista Fasolo, “Benedictus et elevatio simul” (Missa in Dominicis diebus), mm. 1–5, in Fasolo, Annuale (1645)

Ex. 16b. Fasolo, “Benedictus et ellevatio” (Missæ beatæ Mariæ virginis), mm. 1–5, in Fasolo, Annuale

Ex. 17. Elevatione, attrib. Frescobaldi, mm. 16–29. Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Ms. Landsberg 122.

Ex. 18. Adriano Banchieri, “Sonata grave col principale alla levatione,” mm. 8–11, in Girolamo Banchieri, Appendice all’organo suonarino (1638)

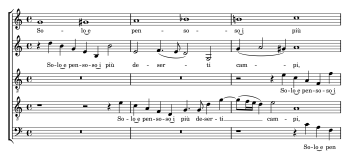

Ex. 19. Luca Marenzio, Solo e pensoso, mm. 1–3, in Marenzio, Il Nono Libro dei madrigali a cinque voci (1599)

Ex. 20. Carlo Gesualdo, Moro lasso, al mio duolo, mm. 34–42, in Gesualdo, Madrigali a cinque voci Libro Sesto (1611)

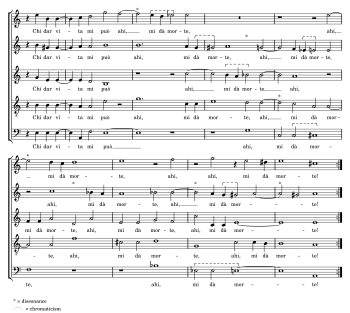

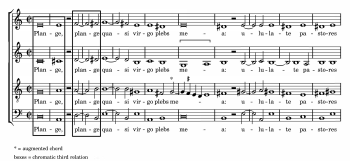

Ex. 21. Marc’Antonio Ingegneri, Plange quasi virgo, mm. 1–10, in Ingegneri, Responsoria hebdomadæ sanctæ (1588)

Ex. 22. Emilio de’ Cavalieri, opening of “Prima die, Lectio prima,” in “Lamentationi del signor Emilio de[’] Cavalieri.” Rome, Biblioteca Vallicelliana, MS O 31.

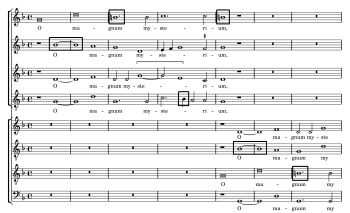

Ex. 23. Giovanni Gabrieli, O magnum mysterium, mm. 1–7, in Andrea Gabrieli and Giovanni Gabrieli, Concerti … Libro Primo et Secondo (1587)

Ex. 24. Giovanni Maria Trabaci, “Durezze et ligature,” mm. 1–9, in Trabaci, Ricercate, canzone franzese (1603)

Tables

Table 1. Organ music for Elevation in seventeenth-century Italian printed sources

Table 2. Organ music for Elevation in seventeenth-century Italian manuscript sources