The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 31 (2025) No. 1

Music and Worship in Mantua: Gonzaga Patronage and Monteverdi’s Role as maestro di cappella; an Investigation and a Rebuttal to Roger Bowers

Jeffrey Kurtzman and Licia Mari*

Abstract

This study responds to two articles by Roger Bowers on Monteverdi as maestro di cappella at the Gonzaga court in Mantua. Focusing on the fifteenth through the early seventeenth centuries, it shows the Gonzaga rulers’ direct interest in and patronage of ecclesiastical institutions beyond the ducal palace—especially the Cathedral of San Pietro, the Church of Sant’Andrea, and the Jesuit Church of the Santissima Trinità—as well as the palace churches of Santa Croce and Santa Barbara and the Oratorio of Santa Croce. It clarifies the location, size, use, and history of the Church of Santa Croce, as well as the accuracy of the plans of Mantua by Gabriele Bertazzolo.

Evidence for Monteverdi’s duties at court relevant to sacred music is often indirect but suggestive. Nonetheless, evidence from the history of polyphonic psalmody demonstrates Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 to be a complete polyphonic liturgical service for practical use. On the basis of biblical exegeses, we suggest that the five sacri concentus, as non-liturgical interpolations, serve as a progressive theological program that functions as an interpretative whole within the Vespers, associating the liturgical response, psalms, hymn, and Magnificats textually with the Virgin Mary, their sacred dedicatee.

PART 1. THE GONZAGAS AND SACRED MUSIC IN MANTUA

THE GONZAGAS AND CHURCHES OUTSIDE THE DUCAL PALACE

3. The Cathedral of San Pietro

5. The Jesuit Church of the Santissima Trinità

CHURCHES AND CHAPELS (ORATORIOS) WITHIN THE PALACE

7. The Church of Santa Croce in Corte: Documentary Evidence

8. The Church of Santa Croce in Corte: Visual and Architectural Evidence

9. The Church of Santa Croce in Corte: The First Oratorio Described in the Petruzzi Visitation Report of 1576

10. The Magna Domus in the corte vecchia

11. The Church of Santa Barbara

CHAPELS WITHIN THE DUCAL PALACE

12. Overview of Spaces for Private Devotion and Services

PART 2. MONTEVERDI AS CHURCH MUSICIAN IN THE GONZAGA COURT, 1590–1612, AS REFLECTED IN THE MASS AND VESPERS OF 1610

13. Performing Forces for the Mass and Vespers of 1610 in Contemporaneous Context

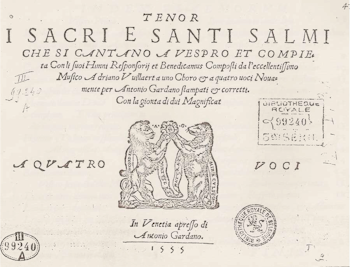

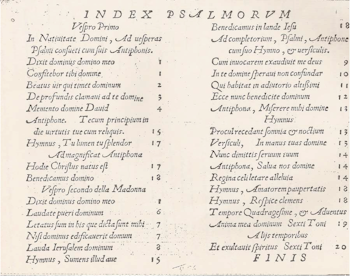

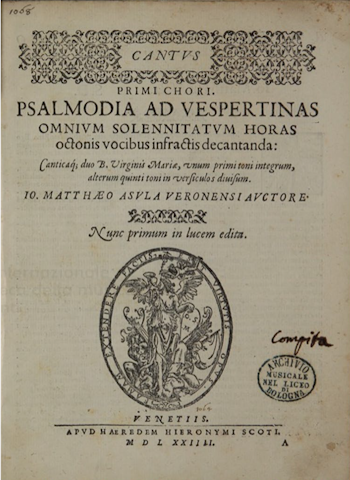

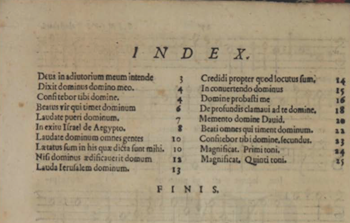

14. The Mass and Vespers of 1610: The Organization of the Amadino Print

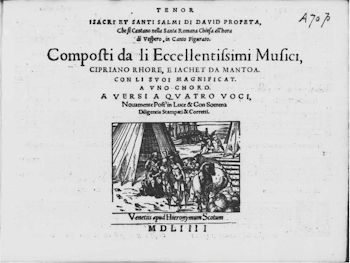

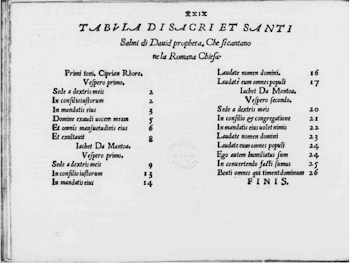

15. Italian Psalm Cursus Settings (1): The Manuscript Tradition of the Fifteenth and First Half of the Sixteenth Centuries

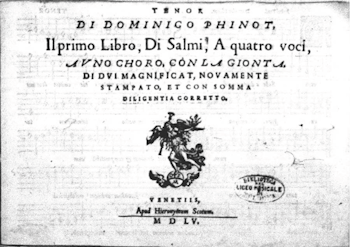

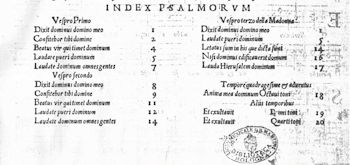

16. Psalm Cursus Settings (2): Psalm Prints of the Second Half of the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries

17. Monteverdi’s Mass and Vespers of 1610: Ave maris stella and the five sacri concentus

18. Liturgical Books, the Caeremoniale Episcoporum, and the Performance of the Liturgy

19. The Use of Motets and Instrumental Music in the Performance of the Liturgy

20. Criteria for Motet Texts Used in the Liturgy

21. Duo Seraphim and the Sanctissima Virgine

22. The Five sacri concentus: Do They Constitute a Theological Program?

23. Conclusions Regarding the Vespers

1. Preface

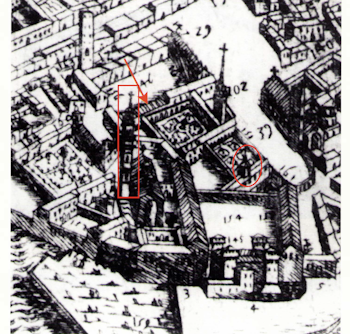

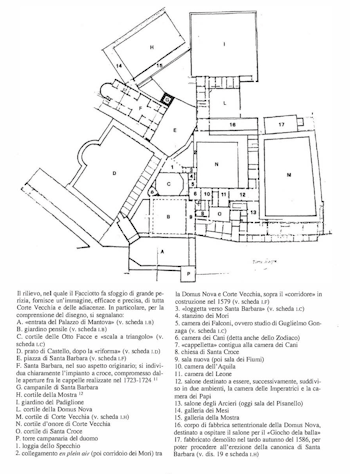

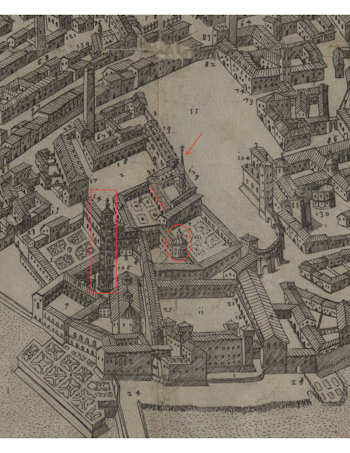

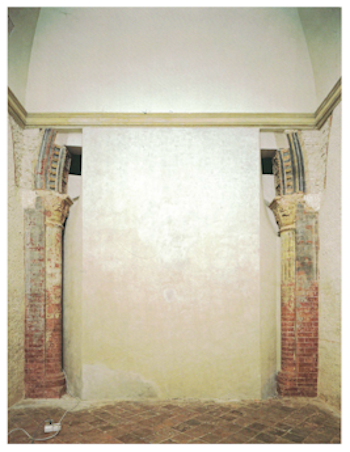

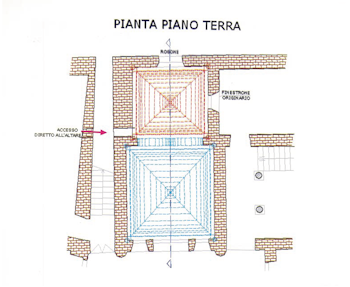

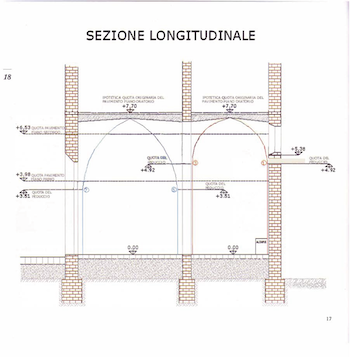

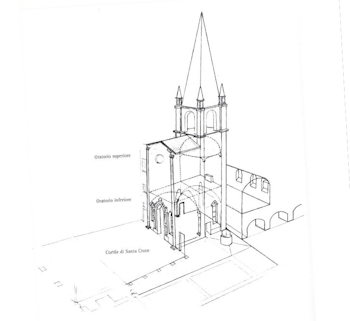

1.1 In 2007, in a chapter entitled “Monteverdi at Mantua, 1590–1612” in The Cambridge Companion to Monteverdi, Roger Bowers, seeking the location within the Gonzaga Palace complex for the performance of liturgical services by the court cappella, declared that it must have been the Church of Santa Croce, located in the complex of buildings known as the corte vecchia of the palace.[1] But the remnants of the former church, drastically remodeled and repurposed by the Austrians in the late eighteenth century, are quite small. Considering this structure “far too small to have accommodated the grand liturgical occasions known to have been conducted within S. Croce church,”[2] Bowers claimed that to accommodate such occasions, involving the court’s full cappella, the church was actually located in the adjacent Magna Domus, a much larger building fronting on the present-day Piazza Sordello (Piazza di San Pietro in Monteverdi’s time).

1.2 However, there is no evidence whatsoever of “grand liturgical occasions” being celebrated in Santa Croce—to the contrary, there is indisputible evidence that the church was much too small for such celebrations, and a fundamental reason for Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga constructing in the decade 1562–72 the largest palatine chapel in Europe. The Church of Santa Barbara was conceived precisely to have enough space for such grand liturgical occasions as well as daily services provided by a college of clerics resident in the palace complex itself (see par 7.7).

1.3 Two years later Bowers published in Music & Letters a much longer article entitled “Claudio Monteverdi and Sacred Music in the Household of the Gonzaga Dukes of Mantua, 1590–1612,” expanding dramatically his thesis regarding the Church of Santa Croce—which he described as slightly larger than the Sistine Chapel—and covering many other topics only adumbrated in his 2007 essay.[3] Readers well-versed in the history of the palace were alarmed by Bowers’s radical claim and its appearance in a major musicological journal. The present authors were also disturbed by the manner in which Bowers pursued his arguments. We determined to challenge Bowers’s primary thesis, and in 2014 presented a joint paper at the Sixteenth International Biennial Conference on Baroque Music in Salzburg, demonstrating the misrepresentation of source materials about the functions of Santa Croce, as well as the lapses of logic and the self-contradictions in Bowers’s arguments.[4]

1.4 In the course of our research in preparation for this paper, it became clear that it was not just Bowers’s claims about Santa Croce church, but numerous other assertions on other subjects that were problematic in their methodology, logic, and reliability. Taking our cue from the practice of investigators in the physical and biological sciences to report on their inability to replicate the results of experiments or studies published in major professional journals, we feel compelled to report on what we consider the invalidity of Bowers’s methods, arguments, and conclusions. We take no pleasure in doing so—indeed, the task is onerous—but we are additionally impelled by the fact that other scholars appear to have been influenced by Bowers’s conclusions (on the assumption that he has handled his sources responsibly and argued his points logically), and we are concerned that students and general readers will be misled, especially since his chapter and article were published in such a prominent anthology and in such a prestigious international journal.

1.5 Bowers’s Music & Letters article, in fact, stands as the most extensive and recent single article published on Monteverdi in many years. It is copiously footnoted, giving the impression of comprehensive scholarship, but only occasionally actually quotes the sources cited. Repeatedly, we found that the sources did not say what Bowers declares they do, and frequently were in direct contradiction to his representations. Furthermore, his narrative includes numerous unsupported “statements of fact,” which are not factual at all. These are not the occasional mistakes that all of us make in reading and interpreting documents or overlooking important sources, but something more systemic.

1.6 In the process of critiquing Bowers’s articles, we have had to access and carefully consider not only the voluminous sources cited by Bowers, but also many others predating his articles that he ignores, especially those that contradict his conclusions. In order to be transparent about the sources we cite, it has been essential to quote and often translate these sources with passages long enough to make clear their context. Readers may decide for themselves if we have fairly or exaggeratedly criticized Bowers’s scholarship by comparing his contentions with the original sources and our translations.

1.7 While this project began as a rebuttal of Bowers’s articles, we felt it important also to provide as much accurate and new information as we could about the issues and subject matter brought forth in Bowers’s essays. This involved exploring historical developments that long preceded the time frame of Bowers’s articles and extended beyond the precincts of the Mantuan ducal palace as a means of understanding the broader context and our own critique. As a result, we offer summaries of accumulated information, including interpretations and insights from relevant primary and secondary sources that, when combined and collated, yield broader perspectives on the issues considered. In this way, we hope to provide our readers with something new and unfamiliar rather than merely a list of criticisms.

1.8 Preliminary readers of our efforts have had difficulties with the merging and interweaving of the two processes, even though our own contributions to new information and outlooks grew directly out of our responses to Bowers’s arguments. The sequence of issues, following that of Bowers’s Music & Letters article, required the reader to be familiar with his article in order to find our own narrative readily coherent. As a consequence, we have decided to separate the two—new information and perspectives on the one hand and our rebuttal on the other—insofar as possible. Therefore, the main text of our essay seeks to inform the reader of the results of our research, even though the topics are prompted by Bowers’s claims, while we pursue the critique of Bowers’s articles primarily in a large appendix (App. 1), often linked from relevant topics introduced and discussed in the principal section, but also readable as a stand-alone text. At times, however, it has been necessary, in our presentation of new information and analyses, to illustrate simultaneously how they differ from Bowers’s points of view. Nevertheless, the reader can focus principally on new perspectives on the topics subsumed under our title and choose when or whether to divert to our critiques of Bowers’s commentaries, arguments, and conclusions.

1.9 The main text of our article is divided into two large sections, intended to cover three principal topics: (1) Gonzaga support of ecclesiastical institutions and sacred music in both the city and the court, particularly during the reigns of Dukes Guglielmo and Vincenzo; (2) Monteverdi’s role in sacred music in the city and the court; and (3) specific issues regarding Monteverdi’s Mass and Vespers of 1610. To understand better the wide context in which sacred music accompanied Gonzaga worship and ceremonies in various churches, the history of these institutions and the immediate, sometimes extraordinary extra-musical settings are described. Music was only one feature of these observances, and the elaborateness and magnificence of multiple artistic aspects of these ceremonies serve to suggest how elaborate and impressive the music must also have been when we do not have direct, detailed descriptions. Unfortunately, it is much easier to recount the actions, prayers, and orations in a ceremony, the vestments worn, and physical structures and decorations designed for that ceremony, than to describe the music. But understanding the role of sacred music, not as an isolated topic, but as an integral part of an entire religious culture requires acquaintance with that culture from many different perspectives, including its support by the ruling family. In fact, the support of religious institutions in Mantua and its environs by the Gonzagas was quite extraordinary—to the best of our knowledge, more extensive than that of any other ruling family in Italy. We have therefore tried to convey a sense of just how remarkable that involvement in many different religious institutions was. Nevertheless, of necessity, ours is not a comprehensive history of that religious culture, which can only be gathered from the many studies and sources cited here, other studies on these and related topics, and studies yet to be written.

1.10 It is easy to forget that Gonzaga financing of the construction, renovations, and repairs of ecclesiastical buildings, the support of ongoing expenses, as well as the commissioning of furnishings, such as choir stalls, choir lofts, and organ lofts, is inevitably also patronage of music, even if that music is confined to plainchant sung by clergy, or by a college of monks or a cloister of nuns. The sung liturgy turned daily services into musical events. As music historians, we tend to be drawn more to polyphony and instrumental music performed by professional musicians or well-trained specialists from the clergy or a monastery, but most music, even in churches with a staff of professional musicians, was still plainchant. Recognition of this fact enables us to understand better how the involvement, both political and spiritual, of the Gonzagas in many different ecclesiastical institutions is inevitably inseparable from their support of music.

1.11 The role of Monteverdi as a composer and performer of sacred music in Mantua is not well documented and has given rise to much uncertainty and, in our view, misapprehension regarding the scope of his activities in the field of sacred music at the court and beyond. We inquire into what evidence there is regarding his role and what it may have included. In addition to remarks at various points in the main text, some relevant discussion appears in Appendix 1, as part of our response to Bowers.

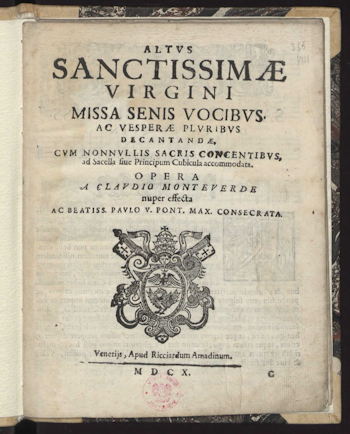

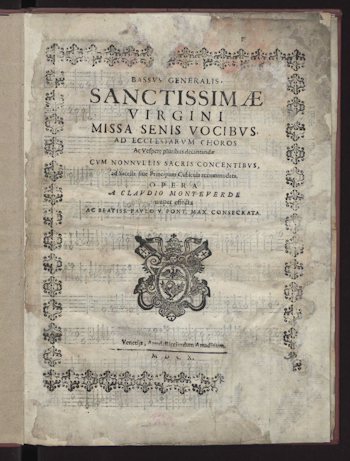

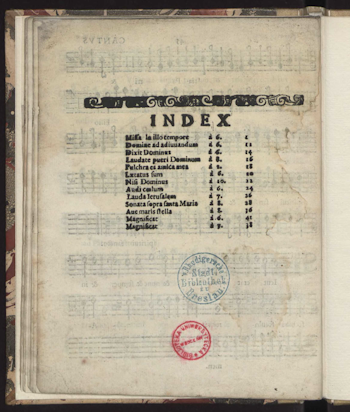

1.12 The most important evidence we have regarding Monteverdi’s activities as a composer of sacred music during his years in Mantua is, of course, his publication of the Missa in illa tempore together with the Vespro della Beata Vergine in 1610. Kurtzman has written extensively about this publication and its relationship to contemporary Italian sacred music, such that there is no need to repeat many of those findings here; rather, we address in several final chapters new thoughts on Monteverdi’s five sacri concentus and Bowers’s arguments about many of the issues that Monteverdi’s print has raised over the years, arguments with which we disagree both in their fundamentals and in many details.

1.13 The scope of our study may reach at times as far back as the early fifteenth century, but we conclude most of our discussion in 1612, with the dismissal of the Monteverdi brothers from court service in July by the new young duke, Francesco IV, who died himself unexpectedly in December of that year. This is certainly not the end of sacred music at the Gonzaga court and Gonzaga patronage of sacred music elsewhere in the city, both of which continued under the new duke Ferdinand and his successors until the end of their branch of the dynasty in 1627. It was the end of that dynasty that prompted the invasion and sack of Mantua by Imperial Troops, fighting over succession of the dukedom and introducing the great plague of 1629–31 to northern Italy. Because of the departure of Monteverdi and a number of other court musicians in 1612 as a cost-cutting measure after the profligacy of Duke Vincenzo I, music at the Gonzaga court to 1627, whether secular or sacred, has drawn less attention from scholars. For those who are interested in this period, we cite a few scholarly studies that include or focus on the post-Monteverdi era until 1630 and the sack of the city, with the loss, undoubtedly, of a large quantity of manuscripts of Monteverdi’s music.[5]

PART 1. THE GONZAGAS AND SACRED MUSIC IN MANTUA

2. Overview

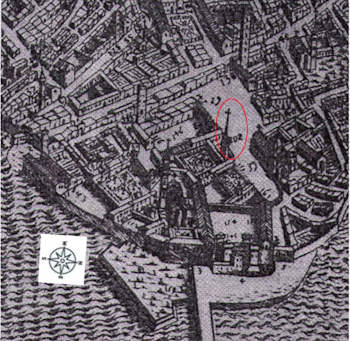

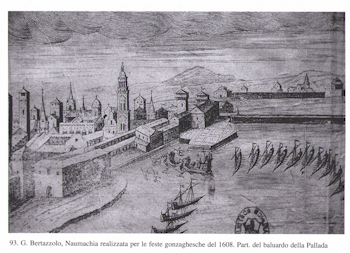

2.1 A principal thesis of Bowers, in both his Monteverdi Companion and Music & Letters articles, is that “it was the duty of the personnel of the duke’s cappella, as officers of his household, to conduct divine service not at large in city churches or elsewhere, but exclusively [emphasis ours] on his premises and in a physical proximity to his person sufficiently close to enable him to be in attendance at any time of his choosing.”[6] (For Bowers’s arguments and our critique, see App. 1, par. 1.1–1.9.) As adumbrated in our preface, the Gonzaga dukes and their families by no means limited their attendance at and sponsorship of divine services to the court, but regularly supported ecclesiastical institutions throughout the city and even in the countryside beyond. And there is ample evidence that the duke’s cappella and individual singers from it performed in some of these venues. The most important churches frequented by the Gonzaga dukes were the Cathedral of San Pietro, directly across the Piazza Sordello from the ducal palace, Leon Battista Alberti’s Church of Sant’Andrea, and the Jesuit Church of the Serenissima Trinità, the latter two also in close proximity to the palace. Others of particular significance to the Gonzagas included the Convent and Church of Corpus Domini, also known as Santa Paola; the Convent and Church of San Francesco; and the Franciscan Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie at Curtatone. Both Santa Paola and San Francesco served as burial sites for members of the Gonzaga family. But many other institutions also received significant support from the Gonzagas: those within the city and close by are listed in App. 2, and most are visible on the 1628 Mantuan map of Gabriele Bertazzolo (Fig. 1).[7]

2.2 Divine services at court took place in a variety of small chapels scattered among the various buildings, with chapels being repurposed and new chapels being constructed from time to time, as well as in the early fifteenth-century Church and Oratory of Santa Croce in the corte vecchia, and the large palace Church of Santa Barbara, constructed in the period 1562–72.

2.3 The history of Gonzaga involvement in these institutions both inside and beyond the palace has been the subject of many detailed studies in recent decades, which reveal much about the role of religion in the consciousness of the family and the importance they placed in publicly demonstrating that consciousness through the construction and reconstruction of buildings, their support of various aspects of the interiors of these buildings (chapels, choir lofts, choir stalls, organs, paintings, decorations, etc.), and their personal presence at services in them, in addition to their choice of particular ones as burial sites. Numerous Gonzaga women professed as nuns in some of the female convents, and some Gonzaga widows retired to convents. Inevitably that support includes music, whether the unadorned liturgy in plainchant or more elaborate celebrations involving polyphony as well as instruments.

2.4 Drawing on such recent studies and archival documents, we have sought to expand the focus of our commentary beyond the sacred spaces in the ducal palace to this much wider sacred landscape, both in the immediate vicinity of the palace and the much larger geographic area of the city and its neaby environs. Our summary of Gonzaga involvement in these institutions is meant to give readers a reasonably comprehensive idea of how broadly and deeply the influence of the Gonzagas permeated their city’s religious establishments as well as to clarify the role played by chapels and churches within the palace grounds themselves. In the course of this exploration various activities of the court cappella and the court composers Giaches de Wert, Benedetto Pallavicino, Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi, and Claudio Monteverdi in these institutions will also emerge.

THE GONZAGAS AND CHURCHES OUTSIDE THE DUCAL PALACE

3. The Cathedral of San Pietro

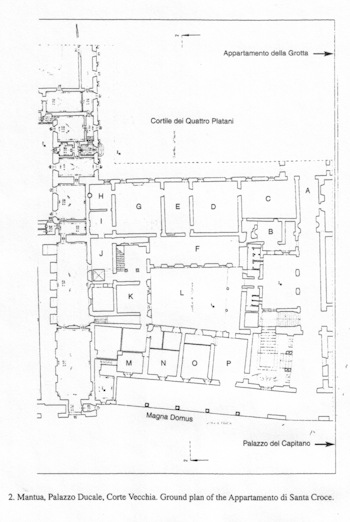

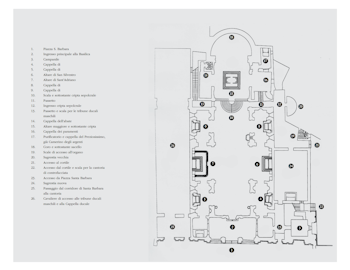

(See Figs. 2 and 3; and see the cathedral’s location on the linked map: Urbis Mantuae Descriptio – Gabriele Bertazzolo, no. 104.)

3.1 The Gonzagas had a special relationship with the Cathedral of San Pietro from the very beginning of their dynasty in 1328. Numerous members of the ruling family were buried there from shortly after their takeover of the government of Mantua.[8] At the end of the fourteenth century, Francesco I Gonzaga commissioned the reconstruction of the temple. During the tenure as bishop of Mantua of another Francesco Gonzaga (1466–83), Pope Sisto IV, in a bull of 23 June 1472, named the Gonzaga family the jus patronati of the church.[9] After Bishop Francesco’s death, Ludovico Gonzaga, already nominated to the post by the dying Francesco, was elected bishop (1483–1511), though on account of Gonzaga family strife, he only became the administrator of the diocese and was never consecrated to perform sacred rites in the cathedral and never lived in the city.[10] At the end of 1510 or the beginning of 1511, Marquis Francesco II Gonzaga (1484–1519) established at court expense a chapel of singers at San Pietro who also sang at court, initiating a long tradition of the movement of musicians back and forth between the cathedral and the court, though no later musicians were simultaneously appointed to both. This group had been preceded at San Pietro by a chapel of eight singers financed by the cathedral chapter. But upon the foundation of the new chapel by Francesco II, these cathedral chapter singers were reduced by half to four, and on 25 August 1511, the remaining chapter singers were dismissed without replacements.[11]

3.2 Upon the death of Bishop Ludovico Gonzaga, also in 1511, his rival Sigismondo Gonzaga was elected Bishop, serving until his resignation in 1521. By this time, “ruling the diocese of Mantua had … become the standard responsibility of the younger sons of the Gonzaga dynasty.”[12] This tradition, combined with the resignation of Sigismondo, led to the sixteen-year-old second son of Francesco II and Isabella d’Este, Ercole Gonzaga, becoming the administrator and subsidiary legate of the diocese. After the death of Cardinal Sigismondo Gonzaga in 1525, Ercole was promoted to the cardinalate on 4 October 1526, taking Sigismondo’s place in the curia.[13] In the period 1540–56 he served as regent to Dukes Francesco III and Guglielmo during their minorities, only being ordained a priest upon Guglielmo’s attainment of his majority in April of 1556. Thus, for more than a decade-and-a-half, Ercole functioned simultaneously as the head of the cathedral and the head of the government but was unable to perform priestly functions. He only received his episcopal ordination in 1561.

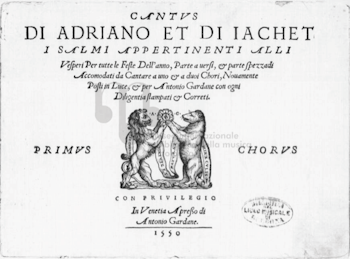

3.3 In 1526 Ercole had hired a singer for his chapel, and in 1531 added another two. From 1548 onward, additional singers joined the “capella dell’Illustrissimo et Reverendo Cardinale,” which also functioned as the cathedral choir, apparently at the full expense of the cardinal himself, since no records of expenditures exist for the ensemble at the cathedral.[14] In 1539 Giachettino di Mantova (Jachet of Mantua, i.e., Jacobus Collebaudi) joined the chapel, listing himself as maestro di cappella (“Chori Sancti Petri urbis Mantuae Magister”) on the title page of his publications.[15] Whereas Francesco II had utilized his chapel in both the church and at court, Ercole denied his singers simultaneous employment at court, and Jachet’s work list includes a very limited number of secular compositions: eleven Latin tributes to individuals, and three “profane” texts, one in Latin, one in French, and one in Italian.[16] Nevertheless, the absence of simultaneous employment does not imply that the choir or individuals from the chapel never performed at court on particular occasions, whether for sacred services in a court chapel or secular entertainment.

3.4 In the middle of Ercole’s stewardship, the interior of the cathedral was destroyed by fire. In 1545 the cardinal assigned its reconstruction to Giulio Romano. The restoration included the completion of a chapel, originally initiated by Bishop-elect Ludovico Gonzaga in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century but left incomplete upon his death in 1511, and the addition of a new organ.[17]

3.5 After Ercole’s death on 2 March 1563, his body was returned to Mantua from Trent, where he had been a papal legate at the Council of Trent, and buried in San Pietro.[18] At some point the cathedral became the parish church of the court, possibly after the twenty-fourth session of the Council of Trent in November 1563, which considered the financial relationship between cathedrals and parish churches and also addressed what was seen as the problem of administration of sacraments to anyone who asked for them. At the end of Chapter XIII of its canons and decrees the Council declared:

The holy council commands the bishops that, for the greater security of the salvation of the souls committed to them, they divide the people into definite and distinct parishes and assign to each its own and permanent parish priest, who can know his people and from whom alone they may licitly receive the sacraments, or that they make other, more beneficial provisions as the conditions of the locality may require.[19]

3.6 The “more beneficial provisions as the conditions of the locality may require” clearly included the ability of the Gonzaga palace’s chapels and churches, even after the construction of Santa Barbara, to serve as venues for members of the family and other court residents to attend mass and receive the sacraments (see par. 3.10, chapters 7–9, and par. 12.9 below).

3.7 After the death of Ercole, Pope Pius V, shortly after his succession, sought to curtail the influence of Duke Guglielmo over the cathedral by revoking the Gonzaga jus patronatus over the church and the right of the duke to nominate the bishop.[20] In 1567 Pius named Gregorio Boldrini as bishop, interrupting the sequence of Gonzagas in that office. But after the passing of Pius in 1572 and the death of Boldrini in 1574, the bishopric returned to the Gonzaga family with the assumption of Marco Fedele Gonzaga to the post in 1574, serving to his death in 1583.

3.8 The line of Gonzagas was again interrupted by Andrea Andreasi, whose death on 23 March 1593 led to another Bishop Francesco Gonzaga (the third by that name), who left his bishopric in Pavia through the intervention of Duke Vincenzo, becoming the new Bishop of Mantua. The forcefulness with which the Duke pressed his wishes on the pope to have Francesco as the new bishop, against the will of the Pavesi, bears witness to how deeply he was willing to be involved in the affairs of San Pietro.[21] After the death of Francesco in 1620, it was another fifty-one years before another Gonzaga, Ferdinando Tiberius, was appointed Bishop of Mantua, the last of the long line.

3.9 Not only had the Gonzagas been principal benefactors of the cathedral and most of the bishops between 1466 and 1620, but the church itself was the scene of numerous important Gonzaga ceremonies. Ferrante Gonzaga (died 16 November 1556), a famous condottiere, was buried in the sacristy of the cathedral after “sumptuous obsequies as befitted such a prince.”[22]

3.10 On 27 April 1561 Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga married Eleonora of Austria with a week of lavish and expansive celebrations attended by an enormous entourage of princes, ambassadors, nobility, and ecclesiastical officials. After a massive entrance of dignitaries into the city on 26 April, the wedding party was solemnly welcomed in San Pietro where the choir of clerics sang, and they heard various orations and received a benediction.[23] On the twenty-seventh the principal attendees heard a Mass sung in the “ornatissima capelletta” of the castle (Castello San Giorgio) by the priest and two members of the cathedral choir.[24] After lunch, the wedding ceremony itself took place in the duke’s own chamber, officiated by Cardinal Madruccio, followed by a ball in the grand hall of the duke’s apartment.[25] On 1 May the royal couple and other princes and dignitaries went to hear Mass at the Church of San Giacomo, returned to the castle for lunch, and after lunch attended Vespers in San Pietro.[26]

3.11 After the death of Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga in 1563, Cardinal Federico Gonzaga, brother of Duke Guglielmo, received the mitre in Rome from Pope Pius IV as the new Bishop of Mantua. Shortly before his arrival from Rome, the prince Vincenzo (born 22 September 1562) was baptized in late April at San Pietro by Monsignor Rossi, assisted by visiting Cardinal Morone.[27] Upon Federico’s return to Mantua on 1 May 1563, he was “received with great festivity.”[28] The funeral of Cardinal Federico, who died less than two years later (22 February 1565), was celebrated with “great sorrow” and “pomp” in San Pietro.[29] San Pietro was the venue for the marriage on 1 May 1582 of the princess Anna Caterina Gonzaga, daughter of Guglielmo, to Archduke Ferdinand II of Austria, for whom the Duke of Bavaria stood as proxy.[30]

3.12 On 29 April 1584, Prince Vincenzo Gonzaga married Eleonora de’ Medici. Donesmondi notes only in passing that for “eight days the entrance of the most serene Eleonora Medici into Mantua was celebrated with royal pomp.”[31] The activities and ceremonies likely equaled in splendor and display the extraordinary celebration of his father’s wedding in 1561, described in so much detail in Andrea Arrivabene’s commemoration book for the event.[32] Although Donesmondi says nothing further about Vincenzo’s wedding, with eight days of festivities planned for what must have been a large contingent of distinguished visitors, it seems impossible that the cathedral was not the scene of at least one liturgical service. Unfortunately, no detailed account of the wedding survives.

3.13 In August of 1587, Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga took sick and died on the fourteenth of the month. Since he had gone to escape the summer heat to the castle of Goito outside the city, his body was carried to and placed in the courtyard of Santa Croce in the corte vecchia, before his funeral and burial in Guglielmo’s palace Church of Santa Barbara.[33] Following official funeral services for Guglielmo on 16–18 September, Vincenzo was crowned in San Pietro on 22 September “in conformity with ancient custom.”[34] Donesmondi declares that the cathedral had been “decorated appropriately for such an event,” and the coronation was performed “with royal pomp … after the Mass of the Holy Spirit had been sung.”[35] Federico Follino, court chronicler and organizer of events, describes in minute detail all the individuals and groups in attendance with particulars of their individual costumes, as well as the decorations and preparations inside and outside the cathedral. “The singers were positioned with their ensembles of trombones, cornettos, and voices,” facing the duke “in a beautiful configuration.” The service began with a most solemn Mass of the Holy Spirit sung by the bishop, “Monsignor Reverendissimo di Mantova,” during which Vincenzo was honored by dignitaries, both religious and lay, enclosing him in a circle.[36] The bishop’s role in the Mass must have been to sing most of the proper portions in plainchant and recite the Gospel and the Epistle, as well as the consecration; the 0rdinary had been composed polyphonically by Giaches de Wert, maestro di cappella of the ducal chapel, and was performed by the abovenamed ensembles. During the Offertory, while many individuals were each being separately incensed, the ensemble of musicians (instrumentalists) performed to alleviate the tediousness of the ceremony “as they were accustomed to do at the hour of the Offertory on the most solemn days.”[37] Once the Mass was completed, the singers and ensembles were quickly dismissed while the attendees left the church.[38] The actual coronation ceremony took place outside, in front of the main door of the cathedral in view of the entire populace. At the duke’s pronouncing his oath on the Evangelist to abide by the ducal decree, a “harmonious consort of trombones” played from the balcony above the main door, and the air echoed “louder than ever” with the “sound of trumpets and drums, joyful voices, the neighing of horses, and so many bells” that “one person could not understand the voice [a word] of another.”[39]

3.14 On 30 May 1593 Bishop Francesco Gonzaga, whose appointment had been fervently pursued by Vincenzo Gonzaga as described above, entered Mantua, which was prepared “to receive him with every possible grandeur and demonstration of love.”[40] As he progressed beyond the Porta Predella, clerics intoned the Te Deum and other spiritual hymns; after the cathedral chapter had placed him on a white horse also dressed in white, he was received under a rich baldacchino, whereupon there was a grand artillery salute accompanied by ringing of all the bells of the city. As he made his way slowly to the cathedral he passed various pious displays to the sound of “dolci concerti musicali.”[41] On 11 February 1594 the bishop celebrated with “solemn display” the consecration of the cathedral, which had never been performed after Ercole Gonzaga’s restoration of 1545.[42] At the beginning of April in the same year, Francesco instituted in San Pietro an annual oration of the Forty Hours, comprising forty sermons the first two days of Holy Week, attended by the entire city.[43]

3.15 The next year Franceso began several physical improvements in the cathedral, including a new altar near the organ and the construction of a new choir “much grander and magnificent” in the apse.[44] Among his projects was a series of frescoes in the dome, the transept, and the apse between ca. 1599 and 1607. Two dates of completion are painted on an arch in the transept: 1605 and 1607. Antonio Maria Viani (ca. 1555/1560–1630) and Orazio Lamberti (1552–1612) were occupied with a cycle of musical angels in the dome, while the Mantuan Ippolito Andreasi (1548–1608) painted narrative scenes in the transept as well as the four Evangelists on the pendentives at the base of the apse.[45] Particularly noteworthy in our context is the nature of the instrumentarium depicted in the hands of the angels—all instruments that formed part of the ducal chapel: lutes, harp, cornettos, transverse flute, possibly a lira da braccio, possibly a viola da gamba, and a short straight trumpet, which is held but not played. Together with the angelic choirs, the emphasis is on the glory of God and the Church, and the strength and mercy of Franciscan spirituality. Absent are trombones and sounding trumpets typically associated with triumph and the Day of Judgment.[46]

3.16 In 1598 Margherita of Austria passed through Mantua on her journey to Spain for her wedding to King Philip III. In San Pietro she heard sung “a motet harmonized with voices and various instruments distributed among several choirs.”[47]

3.17 Perhaps the most famous festivity of the Gonzaga court was the 1608 celebration of the wedding between Prince Francesco and Margherita of Savoy, which included the well-known musical contributions of Monteverdi in the form of the opera Arianna, Il Ballo delle Ingrate, and one of the intermedi to Giovanni Battista Guarini’s comedy L’Idropica.[48] But such an event also entailed religious ceremonies, the first of which took place in San Pietro. Upon her entry into Mantua on 24 May 1608, Margherita was conducted to San Pietro where she was brought into the richly decorated cathedral to the sound of the organ accompanied by “un dolcissimo concerto di musici.” As she adored the Holy Sacrament and the body of Saint Anselmo, the choir sang a motet with the text Veni Sponsa drawn from the Song of Songs.[49]

3.18 These major ceremonies reveal how frequently and intimately the Gonzagas were involved in the cathedral and used it as the venue for important family celebrations apart from their dominance of the bishopric itself. Moreover, they reveal explicitly in the case of Vincenzo’s coronation how the duke’s cappella, and its maestro, participated outside the palace precincts in such grand ceremonies. In fact, the relationship between the choir of the cathedral and the Gonzaga ducal chapel requires further commentary.

3.19 Pierre Tagmann has traced the development of the musical chapel at San Pietro from the beginning of the sixteenth century to 1627, including its relations to the Gonzaga court.[50] His work has been amplified by William Prizer[51] and more recently Licia Mari.[52] The cathedral had the continual services of an organist from 1480, and in 1484 one of the mansionaries became responsible for teaching singing to the clerics.[53] In the late 1490s and into the first decade of the sixteenth century, both the absent bishop, Ludovico Gonzaga, and Marquis Francesco II Gonzaga gradually built up a professional chapel in the cathedral, as noted above, reaching eight singers in 1509, but rapidly decreasing to only four in 1510, one of whom was responsible for teaching the boys who sang in the chapel.[54] Bishop Ludovico died on 19 January 1511, and later that year, on 25 August, as we saw, the remaining singers were dismissed (see par. 3.1). The fate of the early San Pietro cappella was clearly impacted by Francesco’s successful efforts from 1510 to recruit a large number of professional singers and instrumentalists for the court, including Marchetto Cara, Francesco da Milano, Giovanni Angelo Testagrossa, Bernardo Piffero, Bartolomeo Tromboncino, and others.[55] Many of these musicians came from the dissolution of the Ferrarese court chapel under financial stress.[56]

3.20 It is clear that Francesco also intended his ducal chapel to provide services in the cathedral, as already indicated (par. 3.1); as the costs of his recruiting efforts mounted, he wrote to his son in Rome on 10 December 1511, asking him to seek benefices from the pope to support the “heavy expense” of his “excellent new chapel.”[57] In fact, he had tested out his new cappella with a Mass of the Madonna in San Pietro on 12 January 1511, a week before the death of Bishop Ludovico, as well as Vespers at San Francesco on the same day.[58] Prizer, indeed, credits the success of the performance of the duke’s chapel on 12 January with the dismissal of the remaining cathedral singers on 25 August of that year.[59] Francesco continued to seek benefices for his singers, but both Pope Julius II (1503–13) and Pope Leo X (1513–21) themselves soon began recruiting singers away from the marquis’s chapel. Nevertheless, Francesco’s new chapel seems, at least until 1521, to have performed regularly at the cathedral.[60] By 1517, the choir of the cathedral itself, made up of clerics after 1511, had increased from a handful to thirteen by 1517, eighteen by 1528, gradually reaching thirty-two in 1565, plus an unknown number of boys, who were all taught both chant and canto figurato by a choir teacher, who often functioned as, or was eventually named, maestro di cappella.[61] After the death of Francesco in 1519, the court chapel declined substantially under Federico II Gonzaga (1519–40), while his brother Ercole, as bishop of Mantua, cultivated the cathedral choir (see par. 3.3).[62] Explicit documentation of the court chapel performing in San Pietro after 1521 is lacking until the coronation of Vincenzo (see par. 3.13).

3.21 Given the long-standing patronage of San Pietro by the Gonzagas, it is not surprising that Marquis Francesco II had been an active participant in the early development of a professional chapel/court choir. Even though he ceded financial support and governance of the chapel to the cathedral once the choir became only clerical, and there was henceforth never any overlap between the clerical singers and those paid as court singers, the Gonzagas, and eventually even the musical style of the court, continued to exert influence over music at San Pietro.[63] This was particularly evident when court musicians, including instrumentalists (the cathedral did not have instrumentalists on its payroll), supported or even supplanted altogether the cathedral singers for important events celebrated by the Gonzagas in San Pietro, as we have seen in the coronation of Vincenzo and other events cited above (see par. 3.13–3.17). As Tagmann notes, the Gonzagas used San Pietro to celebrate important family occasions that also functioned as political events designed to project the wealth and power of the Gonzagas to other princes, their ambassadors, and their entourages, just as they staged celebratory secular events for the same purpose.[64] The splendor of these manifestations vied with those of other courts, especially in northern Italy, in an effort to secure or bolster alliances in a land riven by long-standing internecine competition and strife.

3.22 The clerical chapel of San Pietro was apparently well-trained enough to sing the four-, five-, and six-voice polyphonic motets and double-choir psalms of its first official maestro di cappella, Jachet of Mantua (1537–59),[65] and his successors, but without instrumentalists and professional singers the clerics themselves would have been incapable of providing the level of magnificence required for such events, including funerals, to glorify the Gonzagas. Entrances into Mantua of the betrothed for their weddings with dukes were particularly lavish, lasting for days. We learn about one such wedding from two letters of Adrian Willaert, revealing that on 21 October 1549, for the entrance of Catherine of Austria for her marriage to Duke Francesco III, Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga had assembled an ensemble of musicians that included two contrabassists and a contralto sent by Willaert from Venice to Mantua. An agent of Willaert’s, Benedetto Agnelli, writes the cardinal that “there are an infinite number of Venetian gentlemen and ladies from Venice who are making arrangements to come to see the ceremonies in Mantua, including the Procuratore Vettore Grimano with his wife and a large company of the principal ladies of Venice.”[66] We have already presented Donesmondi’s and Follino’s accounts of several major Gonzaga ceremonies. Donesmondi, unfortunately, rarely provides information, and that only quite general, about music in these festivities. Yet we know not only from Follino’s valuable and detailed recounting of Vincenzo’s coronation, but from the records of other courts, such as Ferrara, Parma, Florence, and Urbino, with which the Gonzagas competed for recognition and influence, how important musical splendor in consort with visual magnificence was to the prestige and political jockeying of all these ruling families.

3.23 As noted above (par. 3.21), there is no evidence that the cathedral choir ever employed instrumentalists other than the organists. But Follino’s narrative of Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga’s coronation explicitly mentions cornettos and trombones as well as singers (gli cantori con suoi concerti di tromboni, cornette & voci).[67] The term concerto can have a variety of meanings in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries; Follino’s “concerti” clearly signifies mixed ensembles, which differ from the cathedral choir of clerics that sang polyphonic masses and motets with or without the organ, but apparently without the benefit of other instruments. Typically, when referring to the clerics who formed the cathedral choir, Follino and Donesmondi use the term chierici.

3.24 The distinction between cantori and voci is also important. The cantori must have been solo singers from the duke’s chapel, while voci could refer to other supporting singers either from the ducal cappella or from the Duomo choir.

3.25 Another testament to instruments and voices in San Pietro is the report of the multi-choir motet, with voices and instruments, heard by Margherita of Austria in 1598 (see par. 3.16). In the description of Margherita of Savoy’s appearance in the cathedral in 1608 (par. 3.17), Follino reports that “the sound of the organ was accompanied by a sweet concerto di musici.”[68] Here again, he is using the term concerto to refer to a mixed ensemble of some sort. Donesmondi also uses the word concerto in a few instances. Describing the death in 1569 of the exceedingly pious nun, the beatified Paola Gonzaga, Donesmondi declares that “at the hour of her death the other sisters heard choirs of angels sweetly, and in concerto, sing and play musical instruments, [and] it seemed precisely because of the sweetness of the melody that Paradise opened up.”[69] Less precise is his similar account of the death of the blessed Luigi de i Rosatti of Bergamo in 1468: “He too was called by God to the blessed life; a sign of which was the wondrous shaking of his room: and shortly thereafter was heard a concerto of angels, full of grace, celebrating his ascent into Heaven, singing Euge serve bone, & fidelis.”[70] Other instances of Donesmondi’s usage suggest either a mixed ensemble or a composition for mixed ensemble. During the entrance of Bishop Francesco into Mantua in 1593, “dolci concerti musicali” were heard, which could refer to ensembles, the compositions they played, or both. On the other hand, Donesmondi recounts Margherita of Savoy’s entrance into San Pietro in 1608 to the sound of an organ accompanied by “un dolcissimo concerto di musici,” which can only allude to an ensemble. In this period concerto is a word equivocal in meaning, since it often refers either to a mixed ensemble or to a composition for such an ensemble.

3.26 Musici is another term that we find used ambiguously. It is often contrasted with cantori in the phrase cantori e musici, which clearly means “singers and instrumentalists,” but musici is also sometimes used more inclusively, as encompassing both singers and instrumentalists. It is less common for musici to refer to singers alone.[71] Again in 1608, as in Vincenzo’s coronation, Follino is not describing the cathedral’s clerical choir, but musicians drawn from the ducal chapel—in the case of the coronation, obviously led by the duke’s maestro di cappella, composer of the mass ordinary performed on that day.[72] The polychoral motet for Margherita of Austria, performed in the cathedral during her 1598 visit, must also have involved singers and instrumentalists drawn from the ducal chapel; it may have been written by any of the duke’s major composers: Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi, Benedetto Pallavicino, or Claudio Monteverdi. Tagmann infers that on other major state events in San Pietro, such as the wedding of Guglielmo Gonzaga and the wedding of Vincenzo, singers and instrumentalists from the ducal cappella must also have participated, either to supplement the cathedral’s clerical choir or replace it altogether.[73]

3.27 Not only did the court musicians perform in San Pietro, but members of the cathedral choir sometimes performed in the court. As mentioned above (see par. 3.10), during the wedding of Guglielmo Gonzaga and Eleonora of Austria in 1561, Mass was sung in the small chapel of the castle by the “most Reverend Soffraganeo and two musicians (musici) from the Duomo.”[74] On 8 February 1568 the duke provided a concert of eight voices for friends; among the performers was the maestro di cappella of San Pietro, Giovanni Maria di Rossi, who is also recorded as a singer in the court chapel in 1565 and 1567.[75] Giovanni Maria even accompanied Giaches de Wert and other musicians on a voyage to Venice for a theatrical performance there in 1567.[76] Similarly, the cathedral organist Paolo Cantino, participated in the intermezzo of a comedy in 1581.[77] In the winter of 1576–77 Duke Guglielmo on behalf of Prince Vincenzo requested the use for several months of the cathedral’s organist, Annibale Coma, and sent Ruggiero Trofeo, organist at Santa Barbara, to San Pietro in exchange.[78] In addition, musicians that at one time served at San Pietro were later employed in one capacity or another at court: Giulio Cesare Monteverdi (organist), Stefano Nascimbeni, and Simpliciano Mazzucchi.[79] Nascimbeni’s appointment was as maestro di cappella at the palace Church of Santa Barbara, which will be discussed below.

3.28 San Pietro also figures in a letter from Monteverdi of June 1610 to Duke Vincenzo, who was away at his villa at Maderno on the shore of Lago di Garda. Monteverdi reports on auditioning a contralto who traveled from Modena to Mantua seeking employment; as soon as the singer arrived, Monteverdi took him to San Pietro to “sing a motet to the organ”;[80] Monteverdi clearly felt quite comfortable co-opting the facilities at San Pietro if it suited him. After all, there was also the Antegnati organ in Santa Barbara where he presumably could likewise have auditioned the singer.[81]

4. The Church of Sant’Andrea

(See Figs. 4–6; and see the church’s location on the map: Urbis Mantuae Descriptio – Gabriele Bertazzolo, no. 105.)

4.1 Sant’Andrea was another church close by the court with which the Gonzaga family was intimately intertwined and that was of considerable significance to them as the venue for major celebrations as well as a burial site.

4.2 Sant’Andrea derived its importance from its singular relic, a drop of the blood shed by Christ on the Cross when wounded by a Roman lance. Donesmondi published an outline of his early seventeenth-century understanding of the adventurous history of this relic in his Cronologia d’alcune cose più notabili di Mantova of 1616, which, of course, would have agreed with the history of the relic as understood by the Gonzagas and their court.[82] The story Donesmondi tells begins with Longinus, the Roman soldier, who pierced the side of the dying Christ and collected the blood and water that flowed from it:

Longinus, Isaurican soldier, present at the death of Christ, wounded him in the rib, from which flowed royal blood with water that was collected by him. He brought it to Mantua in 36 AD and buried it where the Church of Sant’Andrea now stands. In 804, at the time of Charlemagne, this Most Holy Blood was discovered through a revelation, whereby Pope Leo III came to Mantua and, having verified it, took a small portion to Charlemagne as a gift. In 923 the Mantuans, for fear of the Hungarians, who were devastating Italy, buried part of the Most Holy Blood in Sant’Andrea, and part in [the Church of] San Paolo, where all memory of it was lost. In 1048, through a revelation given by Sant’Andrea the Apostle to the Blessed Adelberto, the Most Holy Blood was again found in Sant’Andrea, and because of the “infinite” number of miracles that followed, Pope Leo IX came to Mantua and having approved it, took another small part back to Rome for display.

In 1055, [Holy Roman] Emperor Henry III came to Mantua specifically to adore the Most Holy Blood; he took a small part to Bohemia and buried the remainder, fearful of the continual infestations of the barbarians in Italy. In 1298, Bardellone Bonacolsi, ruler of Mantua, opened the place where the Most Holy Blood [had been buried] and had it carried in procession with great solemnity through the entire city, where countless miracles occurred, after which he reinterred it where it had been.

In 1354, Emperor Charles IV came to Mantua, secretly opened the same place where the Most Holy Blood was kept, and adored it with great devotion; then he arranged everything as before [and] fourteen years later granted a great many privileges to the Church of Sant’Andrea which are still valid.

In 1402, Francesco Gonzaga, the fourth Vicar of Mantua [Fourth captain of the people], had the aforementioned place opened and took a small part of that Most Holy Blood to Pavia as a gift for the second Duke of Milan, Giovanni Maria Visconti, to make peace. In 1459 Pope Pius II came to Mantua to celebrate a Council, at the end of which, in his presence, the veracity of the Most Holy Blood was disputed (since there were some who denied it) and it was concluded to be true and from the side of Christ. Whereby the pope ordered that every year it be shown in public, as is done.[83]

In 1479 the small part of the Most Holy Blood was found in San Paolo where it had remained there for 556 years; and this retrieval resulted in numerous miracles, whereupon it was afterwards always preserved in San Pietro. In 1521, Duke Federico [II] organized a most beautiful procession to carry the Most Holy Blood from Sant’Andrea to Santa Paola in order to console his sister, the daughter of Marquis Francesco [II], who had never seen the Most Holy Blood, who was making her profession as the Blessed Sister Paola Gonzaga in [the convent of] Santa Paola. There it was adored by all the sisters and revered devoutly the whole day by the city.[84] [Original text in App. 6.]

4.3 The first church actually dedicated to Sant’Andrea arose on the site in 1054, next to a Benedictine monastery constructed in 1037. In 1470 Marquis Ludovico III Gonzaga commissioned Leon Battista Alberti to design a large church as a grand reliquary for the Holy Blood, and in 1472 Pope Sixtus IV granted permission to the marquis to demolish the old church and to set Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga at the head of the new college to run the church.[85] Thus, just as with San Pietro, the Gonzagas took control of the site of Mantua’s most important relic.[86] Alberti died in 1472, and others moved forward with the construction of the church based on the architect’s designs and model, a process that was only completed in the nineteenth century. The crypt, built between 1597 and 1600 by Antonio Maria Viani, was conceived by Vincenzo Gonzaga as a mausoleum for members of the Gonzaga family.[87] Both he and his wife were buried there.

4.4 After the conclusion of the Council of Mantua (1459–60) and the decision that the Holy Blood was genuine, Pope Pius II celebrated First Vespers in Sant’Andrea, along with Mass the next day after a grand public procession in which the blood was displayed, and then Second Vespers. He commanded that the Blood should be displayed annually on the Feast of the Ascension.[88] The pope then ordered three (annual) processions on the three Rogation days preceding the Feast of the Ascension, the third of which was to be to Sant’Andrea, where Mass was to be sung by the bishop or someone deputized by him. At First Vespers on the vigil of the Ascension,

in the presence of the bishop pontifically prepared, with all the officials of the cathedral and the princes of the city and an infinity of the populace, a friar from the Carmelite order, by ancient custom introduced at the time of Marchese Lodovico (although sometimes interrupted), gives a discourse to the people, part in Latin (because of those from beyond the Alps, who used to convene there in great numbers in those early times) and the rest in the common tongue. After which, Monsignor the bishop celebrates a most solemn Vespers: and then displays this Holy Blood to the people (the prince and other persons holding the baldacchino) and he blesses it at a prominent place prepared for this act. The next morning there is a most beautiful procession from the cathedral to Sant’Andrea by laymen only, among which are the city magistrates, with all the doctors, physicians, procurators, and notaries; then all the arts in order under their chosen banners … after the procession is finished, Mass is sung by the bishop and as before the most precious blood is displayed, always with the assistance of the princes and principal gentlemen of the city. At the obligatory hour Vespers is again solemnized in the same manner, and the divine liquid having been displayed, it is returned to its original location, under the sancta sanctorum, with the greatest reverence.[89]

4.5 Thus, from 1460, Sant’Andrea became the scene of a great annual celebration for the city and court on the Feast of the Ascension, with the Gonzagas playing a major participatory role, still continuing in 1611 when Vespers by Monteverdi were performed there. By at least the late sixteenth century, the feast was accompanied annually by a major spring festival, with a fair and elaborate processions that drew visitors from distant locations.[90]

4.6 Just as San Pietro served as the venue for important occasional events for the Gonzagas, so did Sant’Andrea, especially in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Moreover, because of its famous relic, notable visitors were typically taken there by Marquis Federico—later Duke Federico (having been promoted by Charles V in 1530)—to view and venerate it, without a liturgical service necessarily being conducted as part of the visit. Thus, in 1532, the Emperor Charles V, traveling to Spain by way of Genoa from having defended Hungary against Suleiman the Magnificant, visited Mantua. Arriving on the Feast of Saint Catherine, he was invited by Duke Federico to winter there. Charles stayed for three continuous months, lodging in the Convent of Sant’Agnese (see the convent’s location in Urbis Mantuae Descriptio – Gabriele Bertazzolo, no. 110) because of the pleasure he took in conversing there with the Padri Eremitani of Sant’Agostino, and visiting the Holy Blood several times as well as the Santa Casa della Madonna delle Grazie.[91]

4.7 In 1548 Charles’s nephew Maximillian, son of younger brother Ferdinand, both future emperors of the German and Eastern empire, and his son Philipp, the future King of Spain, also came to Mantua to adore the Holy Blood in Sant’Andrea.[92]

4.8 On Tuesday, 22 October 1549, Catherine of Austria made a grand entrance into the city in preparation for her wedding to Duke Francesco III Gonzaga, a marriage that lasted only four months, cut short by the death of the duke on 21 February 1550. After witnessing a mock naval battle on the lake, Catherine’s first stop was in Sant’Andrea, where she was ceremoniously received by the Bishop of Alba and heard a Te Deum, intoned by the bishop and completed by the singers, after which she received the usual benediction and went to the palace. Her wedding was on the next day.[93] As noted above, Cardinal-Bishop Ercole Gonzaga had assembled an elaborate ensemble of musicians for the festivities.[94]

4.9 According to Ippolito Donesmondi, a visit to the Holy Blood was an important feature of a “tourist” stop on 13 July 1585 of three [recte four] young Japanese nobles representing three Japanese kings, who had come to visit Italy. They traveled to Mantua on their return journey after having paid obeisance to the Pope in Rome. The nobles were “sumptuously received and royally treated, and religiously visited the Holy Blood of Christ and the Santa Casa della Madonna delle Grazie to their great satisfaction, after which they continued their journey.”[95]

4.10 Leaving aside the annual Ascension Day celebration, Duke Vincenzo was clearly more invested in Sant’Andrea than his father Guglielmo, for it is during Vincenzo’s reign that a number of major family events took place in Sant’Andrea; indeed, Vincenzo was particularly devoted to the Holy Blood.[96] The birth of Prince Francesco on 7 May 1586 prompted three days of “exceptional manifestations and magnificent celebrations,” including three days of processions to San Giuseppe, Sant’Andrea, and Santa Barbara, the last being the site of Francesco’s baptism.[97] At each church there would have been a major liturgical ceremony, quite possibly involving the court cappella in addition to any musicians employed at Sant’Andrea or the small cappella of Santa Barbara.

4.11 Sant’Andrea was the scene three years later (1589) of Vincenzo’s investiture on the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin (2 February) in the prestigious Order of the Toson d’Oro, founded in 1430 by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy.[98] Vincenzo had received the necklace of the order from Philip II of Spain. The ceremony, conducted in the name of King Philip by the Governor of Milan in the sumptuously adorned church, conferred on the duke the title of Cavalier of Sant’Andrea of Burgundy.[99]

4.12 More than a century ago, Vincenzo Errante published a lengthy article regarding Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga’s third expedition to Hungary to fight the Turks (1601), in which he also chronicled Monteverdi’s participation in an earlier military expedition to Hungary in 1595.[100] A Mass in Sant’Andrea preceded the duke’s departure on this earlier expedition, most likely directed by Giaches de Wert, the court maestro di cappella, and also likely including Monteverdi as either a viol player or singer along with other court musicians.[101] Citing Errante’s documents, Licia Mari summarized Monteverdi’s role in the expedition itself as “maestro di capella for an ensemble that said Mass four or five times per day, probably in plainchant, and sang Vespers on major feast days, probably in polyphony, accompanied by an organ.”[102] Upon his return to Mantua, the Duke heard Mass again in Sant’Andrea on 30 October.[103]

4.13 Vincenzo went on yet another expedition in support of the Emperor against the Turks, leaving on 28 July 1597, “after having made the usual Christian preparations,” which included a Mass and benediction, again in Sant’Andrea. Before leaving he ordered the resumption of construction of the choir of Sant’Andrea according to the designs of Marchese Ludovico II (i.e., the designs of Alberti), which began on 27 August.[104] Vincenzo returned from Hungary on 26 November, and once again his homecoming would have been celebrated with a Mass.[105] We have no information about music during this journey nor whether Monteverdi again accompanied the duke as his maestro di cappella. For a third time, in 1601, Vincenzo answered the call of the emperor to fight against the Turks in Hungary. There is no record of “Christian preparations” for the departure on 18 July 1601, but upon Vincenzo’s return on 18 December the duke gave thanks for his homecoming in Sant’Andrea and “added twelve more priests to the usual number who continually stood in honor and service to the Holy Blood and to pray for his person and all his invincible family.”[106] It is clear, however, from Monteverdi’s letter to the duke of 28 November 1601, written while the duke was on his journey back to Mantua, that Monteverdi was not a member of this expedition.[107]

4.14 Monteverdi did accompany Vincenzo on a healing excursion to Spa in Belgium in 1599. Since any such distant journey and lengthy absence inevitably entailed a variety of dangers, there was likely again a public Mass in Sant’Andrea prior to departure. There would, of course, have been no reason for the duke to include Monteverdi in his entourage in 1599 other than to provide both secular and sacred music, perhaps again as maestro of a small cappella of court musicians. Unfortunately, we don’t have the names of the other musicians who must have accompanied him, and the only indication of his activities is the series of rhetorical questions posed by his brother Giulio Cesare Monteverdi in his 1607 response to the attacks on Claudio by Giovanni Maria Artusi.[108] The duke returned to Spa for similar healing in the summer of 1608, after the completion of the wedding festivities between Prince Francesco and Margherita of Savoy.[109]

4.15 On 5 August 1594 Eleonora of Austria, mother of Duke Vincenzo, died. Her body was brought to Santa Croce in Corte for three days of viewing, after which it was carried in solemn procession to the Jesuit Church of the Holy Trinity, which she had patronized and whose transept was not yet completed. There the usual Office for the Dead was solemnly performed, and she was buried in front of the high altar. It was immediately ordered that regal obsequies be held in Sant’Andrea as the place most suitable to raise a magnificent catafalque. The catafalque, described in detail by Donesmondi, was an enormous square structure reaching up to the vault, with four facades, each with a doorway, and in each corner four great columns in a square. The entire structure was surmounted by a spacious cupola surrounded by a high balcony and topped by a large cross, the whole supported in the manner of a tabernacle by four angels. The spaces in the facades were filled with fifty angels and other smaller figures representing various members of the House of Austria, each with a its own most prominent virtue and motto. Under the central cupola an effigy of Eleonora, dressed as a widow, was placed on a bier, around which were multiple eagles that appeared to be of bronze, and other figures as well as various crests of the Austrian and Gonzaga families with their mottos. The pedestal had four large steps by which one could walk around the structure, adorned with ornaments and a large quantity of candlesticks holding very large torches. The entire church inside and out was draped in black, painted with white and dark depictions of acts of Christ imitated by Eleonora. Four large statues representing Mantua, Casale (Monferrato), the Po, and the river Mincio were placed in the entrance. It took until the end of September to design and bring the project to fruition, at the cost of several million scudos. Donesmondi’s description gives us an idea of what he could mean by his use of the term suntuoso or sontuoso apparato, though elsewhere the apparati he mentions, but doesn’t describe, were probably not quite this lavish.[110]

4.16 The actual obsequies took place on 1 October, with the Primicerio singing a pontifical Mass, assisted by the Abbot and officials of Santa Barbara, as well as the abbots of six other churches. Also present were the principal friars of all the religious orders in Mantua, the canons of the colleges, Duke Vincenzo, Don Ferrando di Guastalla, the Gonzaga family, and many ambassadors of various princes. The ceremonies were discharged with incredibil grandezza and included an oration on the merits and pietà of Eleonora by a friar brought especially from Padua for that purpose. On the third day afterward, the ceremonies were repeated in the same manner, though with a different speaker praising the deceased.[111]

4.17 The presence of the Holy Blood, and the attention of Vincenzo to Sant’Andrea, resulted at the beginning of 1607 in Pope Paul V granting perpetual indulgences, and among others, a plenary indulgence on the feasts of Sant’Andrea and the Ascension, and on Good Friday. On all other Fridays of the year, along with other feasts, the indulgences were limited but generous.[112]

4.18 1608 was a highlight year for the Gonzagas and Monteverdi, centered around the grand festivities celebrating the wedding of Francesco Gonzaga and Margherita of Savoy, which put an end to squabbles by the dukes of Savoy and Mantua over control of Casale Monferrato. What is best known about these festivities are the theatrical events composed by Monteverdi, Il Ballo delle Ingrate, the opera Arianna, and his lost intermedio to Giambattista Guarnini’s play L’Idropica. But the Church of Sant’Andrea played a significant role as well. After a solemn Mass in a highly decorated Santa Barbara on Pentecost Sunday and the subsequent luncheon, the noble guests went to Sant’Andrea where Vincenzo founded his new Order of the Redeemer, a knightly order with his son Francesco as its first head. The choice of Sant’Andrea for the event was obvious because of the Holy Blood, which played a part in the ceremony on 25 May 1608 and was symbolized in the pendant of the chain worn by the members. The church was, of course, specially decorated for the ceremony, which took place on a platform erected for it on the left side of the nave. The ceremony’s principal function was for each new inductee to swear to uphold the constitution of the order, which included defending the Catholic Church, the pope, and the prince (Vincenzo) from their enemies, saying Mass every day, attending meetings and festivities of the Order, and defending the honor of widows, orphans, and wards.

4.19 After Prince Francesco was inducted as the leader of the new order, fourteen others, named by Follino and Donesmondi (six of whom had the surname Gonzaga), were similarly sworn to the constitution. Each was fitted with a cloak and the necklace of the Order, displaying on a pendant a medallion with the image of the tabernacle in which the Holy Blood was kept.[113] Once the ceremony was completed, the Te Deum was sung, and after the bishop, pontifically dressed, who had come with his entire chapter and clerics in procession, pronounced an oration, Vespers was sung. At the conclusion of Vespers, the ceremony of displaying the Holy Blood took place, raising it from the high altar to which it had been transported from the sanctuary where it was conserved, and placing it on a platform prepared for it under a baldacchino held aloft by four of the newly inducted knights, all of them members of the Gonzaga family. At the end of this ceremony the duke led a procession to the door where all took off their cloaks, but keeping their necklaces, mounted their horses and returned to the court.[114] Five days later, on 30 May, Sant’Andrea also hosted the wedding guests at Mass with an exhibition of the Holy Blood.[115]

4.20 Sant’Andrea also drew worshippers for other types of events. For example, not long after the guests had departed following the wedding ceremonies of 1608, the much-beloved Bishop Francesco Gonzaga fell ill from too much exertion in the summer heat, provoking prayers throughout the city for his health. On 25 July a general procession from the cathedral to Sant’Andrea culminated in a sung Mass in honor of the Holy Blood and prayers for the bishop, and on the next day the priests of the cathedral made the same procession to hear another Mass and offer their prayers. The day afterward the bishop’s recovery became manifest, and on 30 July another barefoot procession of the city went to the Madonna delle Grazie di Curtatone to sing a Mass of Our Lord in gratitude.[116]

4.21 On the vigil of Pentecost 1610 (30 May), an impressive funeral was held in Sant’Andrea for Giulio Cesare Gonzaga, Prince of Bozzolo, who had died a short time before. Because he had been the first Cavalier of the Order of the Redeemer to perish, on the next day there were created other new cavaliers with the same ceremonies in Sant’Andrea.[117] The newly appointed governor of the church was Lodovico Gonzaga, son of Marchese Prospero Gonzaga, on whom Pope Paul V had recently conferred the title of Primicerio of Sant’Andrea. Lodovico solemnly took his post just five days later “to the joyful applause of everyone.”[118]

4.22 During the night of 1 February 1611, Eleonora de’ Medici, the wife of Vincenzo, suffered a debilitating stroke, causing the cessation of Carnival festivities throughout the city and prompting a solemn Mass to the Holy Blood in Sant’Andrea every Friday during Lent.[119] Eleonora lingered on through the spring and summer, but died on 9 September. Donesmondi described what followed:

Vincenzo was away in Casale Monferrato and receiving such bad news lamented sorely; he ordered that the funeral and burial not take place until he returned, which he did at the beginning of October. Meanwhile a splendid catafalque was raised in Sant’Andrea, and then on 8 October, in the evening, she was buried with regal obsequies in a small, separate chamber in the sanctuary where the Holy Blood was preserved. In the following days Divine Offices were said for her with much pomp.[120]

4.23 Donesmondi does not provide any further description of the “superbissimo catafalco.” Whether it approached the size and elaborateness of that of Vincenzo’s mother, Eleonora of Austria, described above (see par. 4.15), we do not know.

4.24 It was only a year after Eleonora’s stroke, when her husband, Duke Vincenzo, developed a fever, pains, and a serious catarrh on 1 February 1612, bringing him close to death in three or four days and leading to public prayers in Sant’Andrea, where the Holy Blood was exposed to the populace on the altar. In other churches of the city, and particularly the cathedral, the Holy Sacrament was also exposed and orations delivered, upon which the duke’s fever and its effects subsided. But after a brief respite, the fever returned and Vincenzo died on 18 February.[121] His body was first brought to the Church of Santa Croce in Corte, “as was customary for embalmed princes,” and after several days of public visitations, carried to Santa Barbara, then on 10 March to Sant’Andrea where, as in earlier Gonzaga funerals, it was placed on a high, magnificent catafalque. After the bishop had performed the obsequies, he was buried in the same small chamber where his wife Eleonora had been laid to rest the previous October.[122]

4.25 On 8 June 1612, much more elaborate funeral obsequies in Vincenzo’s honor were celebrated with royal magnificence and a large display (nobilissimo apparato) in Sant’Andrea.[123] Around the royal catafalque were eleven large paintings depicting the principal acts of the eleven Gonzaga princes who had preceded him. Under each painting was a representation of the tomb of each prince with an effigy of each in fake marble. Alternating with these were another eleven paintings of the accomplishments of Vincenzo, parallel to each of those of his predecessors, illustrating that he had incorporated in himself all the heroic virtues of his antecedents combined. Donesmondi describes the construction as “the most elaborate in a long time in the city of Mantua, built at incredible cost, drawing many visitors from beyond Mantua to see it.”[124] A sketch preserved in the Vatican Library shows the position of civil and religious authorities during the ceremony, an issue that generated concerns about priority in seating. The singers were situated in the apse, and the Holy Blood was exposed to the public.[125] We find it highly probable that the ducal chapel, including Monteverdi as its maestro di cappella, were the principal musical forces for the services in Sant’Andrea, even if the musical chapel of Sant’Andrea also took part.

4.26 Offices were also planned for the following day, but not performed; the apparatus was taken down because of the Feast of Pentecost (10 June, with vigil on 9 June), where the Holy Blood was displayed.[126] In contrast to Vincenzo’s coronation, held in the cathedral “in conformity with ancient custom,”[127] his heir Francesco, because of the Pentecost celebrations, was crowned privately in the Castello followed by a public ceremony of gratitude in Santa Barbara and the casting of coins among the populace before the new duke returned to the Castello.[128]

4.27 Francesco also appears to have favored Sant’Andrea in his short reign. In early September 1612, the new duchess, Margherita of Savoy, gave birth to a daughter, who must have been sickly from the outset, for contrary to custom she was immediately baptized and shortly thereafter died.[129] She was buried in Sant’Andrea with a “funeral like no other”:

The duke had ordered that in addition to the priests of the church, all the poor children of the orphanages of Mantua, along with other Mantuan children, numbering over 500, were invited and dressed in black, covered with a small surplice, as if they were so many clerics, who accompanied the wake in the early evening with burning torches, singing the psalm Laudate pueri Dominum.[130]

4.28 At the end of November, Francesco’s son and heir, Prince Lodovico, who had just passed 18 months of age, became feverish; he died of smallpox on 3 December. He was buried three days later in Sant’Andrea with ceremonies similar to his sister’s. He was followed in death less than three weeks later by his father Francesco, on 22 December, also struck down by smallpox. His brother Cardinal Ferdinando buried the duke in Santa Barbara, and his funeral was celebrated there a few days later with proper display.[131]

4.29 The first indication we have of a choir in Sant’Andrea appears in a letter describing the first performance of Marquis Francesco II Gonzaga’s new musical chapel in San Pietro. This letter, published by William Prizer in 1977, makes it clear that in 1511 there was a choir in Sant’Andrea, familiar to the public (see par. 3.20). The letter evaluates the duke’s newly acquired chapel, noting that the general populace preferred that of Sant’Andrea: “In accordance with a great desire to hear these singers, who, even though they were truly equal to the best in their profession, the populace nevertheless praised much more the singers of Sant’Andrea; and there were many who [despite our inferior numbers] liked much more our voices.”[132]