The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 29 (2023) No. 1

Meter, Tactus, Tempo, and the Perception of Speed in the Keyboard Works of Johann Jacob Froberger

Akira Ishii*

Abstract

The new types of music in Italy around the year 1600 led composers to introduce innovative rhythmic notation. Froberger, however, utilized only a few simple time signatures, though he clearly intended his compositions to include a variety of tempo changes. He cleverly interweaves various rhythms and rhythmic figures to make the tempo fluctuate without disturbing the tactus. This is evident especially in his strict contrapuntal compositions, but the idea of strict proportions can also be observed in his French-style music. There is apparently a close tempo relationship between the movements of the dance suites.

3. Frescobaldi’s Approach to Tempo

4. Meter, Tactus, and Tempo in Froberger’s Contrapuntal Compositions

5. Froberger’s Method of Varying Tempos

6. Tempo Relationships among the Movements of Froberger’s Suites

7. The Relationship between Allemandes and Gigues

1. Introduction

1.1 While the new types of music that began appearing in Italy around the year 1600 led composers to introduce innovative rhythmic notation, the influence of the mensural system of the Renaissance persisted well into the seventeenth century. Still, composers gradually began to modify the old practice to express new ideas, which were often creative, progressive, and wildly imaginative. One of the most difficult elements of notation was the indication of tempo.[1] Composers implied it with a variety of proportional time signatures, many of which were difficult to understand and thus soon went obsolete.

1.2 One of the composers who successfully conveyed his intentions was Girolamo Frescobaldi, with whom Johann Jacob Froberger presumably studied in Rome in the 1630s. With respect to meter and tempo, however, Froberger did not follow Frescobaldi’s methods exactly. Froberger’s notation was much simpler in appearance and used significantly fewer types of time signatures. This does not mean that Froberger’s music shows no complexity of tempo fluctuation. A careful study of meter reveals that he had a firm conception of tempo. He makes his music profoundly expressive not only by allowing the tempo to fluctuate but also by changing the perception of it. At the same time, however, Froberger intended his compositions to have underlying pulses that would provide a sense of unity within a composition.

2. Tactus, Meter, and Tempo

2.1 In the Renaissance, performers relied on a steady tactus for the rhythmical unity and coherence of a musical work, especially when convoluted polyphony was present. A tactus consisted of two parts of equal or unequal lengths, indicated in performance by hand motions. A downward gesture indicated the beginning of the tactus (the modern “strong beat”); an upward gesture indicated the end of the tactus in an accompanying pulse (the modern “weak beat”). In duple meter the two parts were equal in duration, but in triple meter the first part was twice as long as the second, since the hand movement was thought to be able to show just two gestures, not three.[2] In principle, the speed of the tactus would remain the same even when the music shifted from duple meter to triple or vice versa. What determined the intuitive feeling of the speed of a musical work was the subdivision of the tactus. If a tactus was filled with notes of rhythmically small value such as eighth and sixteenth notes, the velocity would seem to increase (though paradoxically, the tactus might actually slow down to accommodate all those small notes). In short, the tempo could be changed not just through proportional time signatures but also by using diverse proportionally divided notes.

2.2 In practice, the speed of the tactus could be variable.[3] Pier Francesco Valentini (1586–1654), for instance, says that the tactus can be taken sometimes adagio, sometimes presto, and sometimes in between presto and adagio, depending on the style of the composition, or the sense of the words.[4] Valentini’s idea is in accordance with what Frescobaldi wrote in the preface to the second edition of his first book of toccatas, published in 1616. There he states that the speed of performance should be altered in a manner similar to that of “modern madrigal practice,” where it is modified according to “the expression [affetti] or the sense of the text.”[5] Giulio Caccini says the same in Le Nuove musiche (1602).[6] Tempo could be modified for practical as well as artistic reasons. According to Frescobaldi’s instructions for the performance of his partite (variation sets), variations containing “passage work and expressive figures” must be played slowly, but variations without such passages “should be played fairly quickly.”[7]

3. Frescobaldi’s Approach to Tempo

3.1 Frescobaldi’s words on tempo also appear in the first volume of his Capricci, published in 1624.[8] There he writes instructions such as “the cadences should be held back somewhat before the next passage is begun” and “the beginnings should be taken adagio in order to give more spirit and beauty to the following passage.”[9] What he focuses on here is the speed of the surface pulse (or beat), the external element of meter governed by the tactus, more than on the tactus itself. In the same preface, Frescobaldi offers a more comprehensive view of the pulse: “In the trippole or sequialtere: if they are major, one must play adagio; if they are minor, somewhat more allegro; if three semiminims, more allegro; if there are six against four, one must take their tempo by an allegro beat.”[10] He is discussing here the characteristics of different types of triple and compound meter and suggests that notes of small value such as quarter notes needed to be played faster than the others. To be more specific, whole notes, three of which constitute the trippole [tripla] or sesquialtera maggiore, should be taken slower than half notes, three of which make up the trippole [tripla] or sesquialtera minore. Quarter notes in 3/4 or 6/4 should be the fastest. In other words, the velocity of the pulse is determined by the rhythmic values of the predominant notes.[11] Frescobaldi, however, does not say the tempo needs to follow a proportion; in fact, the phrase “somewhat more allegro” (alquanto più allegre) suggests that the half notes are not precisely twice as fast as the whole notes.

3.2 Furthermore, the velocity of the tactus may change without a new time signature. For the duple-meter pieces in Capprici, Frescobaldi utilizes only the common time signature C, but different tempos even within a piece may have been intended. Etienne Darbellay observes that the duple-meter measures are sometimes shortened by half in those places where a high number of fast-moving notes such as eighth and sixteenth notes appear; thus, a passage in predominantly white notes with bar lines spaced at the interval of a breve gives way to a passage in black notes with bar lines spaced at the interval of a semibreve. From this he concludes that the tempo of the tactus in the black-note passage is meant to be slower than that in the normal (white-note) duple-meter passage, though of course the effective tempo of the black notes will be fast.[12] The various tempos, however, do not necessarily suggest that the speed of the tactus was to be freely modified at will. As Margaret Murata points out in her study of Frescobaldi’s use of time signatures, his practice after all is “rational, not very arcane, proportional, and playable.”[13]

4. Meter, Tactus, and Tempo in Froberger’s Contrapuntal Compositions

4.1 In comparison with Frescobaldi, Froberger utilized far fewer types of time signatures in his contrapuntal works (see Table 1).[14] Nearly all sections in triple meter, for instance, are written with the signature 3. The only exception is the 9/3 in the third canzona in the 1649 autograph (FbWV 303). One of the reasons for the repetitive usage of the time signature 3 is that in notating triple meters, Froberger did not distinguish between the normal tactus alla semibreve (three half notes per tactus, as in, for instance, Capriccio VI, FbWV 506) and a presumably faster “common triple” of three quarter notes, as in Capriccio V, FbWV 505): the signature is 3 in all cases. In the sections in compound meter, two signs appear: 6/4 and 12/8. There are no apparent differences between the two; all measures in compound meter are alla semibreve (two dotted half notes per tactus) and show similar rhythmical figures. All simple duple meter sections are marked C, except for the brief final section of the first toccata in the 1649 autograph (FbWV 101). The unique signature there is 8/12C, with which Froberger attempts to indicate the tempo reduction: the eighth-note triplets in the previous section, marked 12/8, give way to regular eighth notes (the latter barely audible under florid embellishment).

4.2 Froberger also avoids frequent changes of meter. In the majority of his contrapuntal keyboard pieces, shifting to a different meter occurs no more than twice, many pieces retaining the same time signature throughout the composition. There are some large-scale pieces in which the meter changes four times or more. Only one work shows a meter shift at five places (Capriccio II, FbWV 502). It seems clear that Froberger does not rely extensively on varied time signatures to achieve tempo fluctuation. On the contrary, he avoids changing meters, thus largely maintaining a fundamental pulse, the tactus.

4.3 In general, Froberger’s bar lines appear regularly. He consistently places them so that each notated measure contains two tactus. In most meters—all except the fast triple meter with quarter note beats—that means bar lines appear after every breve (every two whole notes or dotted whole notes) whether the music is in duple, triple alla semibreve, or compound meter. The only exceptions are at the ends of sections where the meter changes or is about to do so. There Froberger might either augment or diminish the duration of a measure. A good example can be found at the end of the first section of Ricercar V (FbWV 405). Here the final tactus of the duple section, the first half of a normal measure, is followed immediately by the introduction of triple meter (see Fig. 1). The sense of conclusion is mitigated by the incomplete metrical unit, and the introduction of the new theme emphasizes the music’s continuity. From the point of view of the regular measure, the flow is disrupted, but the semibreve tactus and the beat within it remain intact, with three half notes in 3 at least theoretically equal in duration to two half notes in C—provided, of course, that the speed of the tactus does not change in the new section. In any case, the tactus is scarcely audible because it moves too slowly. For this ricercar, perhaps the pulsing beat (every half note in duple meter) can be set, for example, at MM=48. This makes the velocity of the tactus MM=24.

4.4 In some places, the incomplete measure appears to begin the new segment. For example, Froberger prolongs the measure at the end of the triple-meter section of the same ricercar (FbWV 405) by introducing the new time signature, C, at the end of a complete measure in 3; thus, the measure includes an additional tactus, this one in duple meter (see Fig. 2). The melodic theme for the new section, on the other hand, does not begin until the following measure. The final whole note in the expanded measure is in reality the cadential chord of the triple-meter section. Froberger could have postponed the duple time signature until the beginning of the new theme, but perhaps he wanted to give the performer advance notice of the new segment, deemphasizing the conclusion of one section and placing more emphasis on what was to come.

4.5 Froberger also sometimes augments the last measure of a section. An example of this is found in the third canzona of the 1649 autograph (FbWV 303). The final measure of the first section in duple meter includes an extra whole note (see Fig. 3, which begins in the middle of a measure). If Froberger had intended the conclusion of the segment to be robust, he probably would have written a double whole note before the new meter. The extra whole note suggests instead that the music goes on.

4.6 In some cases, a meter change occurs in the middle of a measure that is neither augmented nor diminished. The final measure of the section marked 3 in the fifth fantasia of the 1649 autograph (FbWV 205), for example, shows a cadence. Its resolving note, however, is also the first note of a new passage in duple meter. In other words, Froberger avoids a firm ending and jumps into the following segment by overlapping the two sections (see Fig. 4). The semibreve tactus moves seamlessly from three half notes in 3 to two half notes in C. The piece continues, and so does the beat.

4.7 These occasional irregularities suggest that Froberger did not intend a conclusive pause at the end of each section of a composition. He seems to have wanted the beat to continue at a steady pace. Froberger does, however, adopt Frescobaldi’s manner of free-style composition and frequently writes his music in that style, and while in the publicly available autographs such passages lack any inscriptions or signs to let the performer know when the tempo should fluctuate, one of the non-autograph sources for Froberger’s works that is closely related to the composer’s autographs often shows the instructive word “discrétion” as well as unusual-looking signs to indicate the measures in which the free-style playing is expected.[15] (More will be said below about the placement of some such instructions.) Nonetheless, the evidence given here suggests that Froberger wanted the fundamental pulse to be kept rather steady.

5. Froberger’s Method of Varying Tempos

5.1 To avoid letting his music become rhythmically uninteresting, Froberger varies the intuitive feeling of tempo by writing numerous types of proportionally divided notes. The idea is simple and not new to Froberger. One of the primary ways to indicate the change of speed was to alter the meter, with which, however, the velocity of the beat in a new section could not be precisely indicated. This is especially true in Froberger’s music, where only a few types of time signatures are utilized. What is important, then, is the number of notes written within a tactus or surface beat. The music in duple meter, for instance, is often predominantly filled with half notes. The sense of speed would increase when the meter changed to triple because there would be three half notes per semibreve tactus instead of two. If the duple meter section displays, on the other hand, mostly quarter and eighth notes, the tempo in triple meter feels slower, the tactus containing only three notes instead of four or eight.

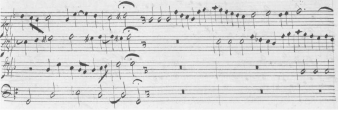

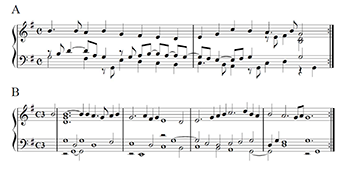

5.2 In the early seventeenth century, composers began marking tempo changes in their music. In the final edition of Il primo libro delle canzoni, published in 1634,[16] for instance, Frescobaldi clearly indicates speed modifications by writing such words as “Adasio” and “Alegro.”[17] In this edition these inscriptions appear much more frequently than they did in the earlier edition of the canzonas, published in 1628. In the first canzona for two voices (canto solo and basso) in the 1634 edition, for example, “Adasio” appears at the beginning of the duple-meter cadential measures (mm. 41–43). Frescobaldi then writes “Alegro” at the start of the new fugal section, still in duple meter, in m. 44 (see Ex. 1). In the Adagio measures, Frescobaldi writes a series of half notes, but for the new fugal subject in the following Allegro he utilizes faster-moving quarter and eighth notes. The number of notes per tactus, therefore, increases when the fugue begins, resulting in tempo acceleration. Perhaps the instructive word “Alegro” is unnecessary, but Frescobaldi put it there to make sure the performer would know what comes next.

5.3 Unlike Frescobaldi, Froberger did not leave any sort of tempo markings in his autographs, but his intentions can be easily observed in his music. For instance, he frequently modifies the number of notes per tactus without changing meters. Ricercar I (FbWV 401), for instance, comprises four fugal sections with no meter change. At the beginning of the opening section, the predominant notes making up the fugal theme are whole notes and half notes. Some quarter notes appear in its countersubject, but they are scanty (see Fig. 5a). When a variant of the fugue subject appears in the top voice in m. 16, motivic figures including eighth notes are introduced (Fig. 5b). Froberger then writes a succession of quarter notes interspersed with the eighth-note motives in the following measures (Fig. 5c). His intention up to this point is to gradually increase the intuitive tempo. At the end of the section, where the fugue subject appears for the last time in the bass, however, the speed decreases because quarter notes and eighth notes are infrequent (Fig. 5d). Here Froberger most likely wants a solid conclusion for the first section, with a well pronounced cadence.

5.4 From one section to another of Froberger’s strict contrapuntal compositions, the intuitive feeling of the tempo changes more than once. Froberger usually begins a piece with a fugue subject consisting of mostly slow-moving notes. He then increases the intuitive tempo in the subsequent sections by changing meter or by modifying the division of the tactus. In many cases, the tempo slows down at least once before the end of a composition. Froberger often reduces the speed by introducing improvisational cadence figures that require a temporary halt of the tactus. He then brings back a lively tempo by writing fugal themes filled with notes of rhythmically small value. This type of tempo-modification scheme is well illustrated in the third ricercar of the 1656 autograph (Ricercar IX, FbWV 409): see Table 2. Here Froberger writes an opening section with mostly half notes and some quarter notes. The music speeds up in the second section, which changes to triple meter. Half notes are still featured, but at three per tactus instead of two. In addition, Froberger begins adding quarter notes to the fugue subject, further creating a sense of acceleration. When duple meter comes back in m. 55, the tempo slows down because there are now only two half notes per tactus. In the last section of the piece, the intuitive tempo increases once again because the countersubject there consists mostly of quarter and eighth notes.

5.5 Froberger’s canzonas and capriccios often show a different type of tempo scheme. The opening fugue subjects of these pieces usually consist of lively figures with fast-moving notes such as quarter and eighth notes. It would be difficult to accelerate further; instead, the music decelerates as it progresses. The original fast tempo is usually brought back in the final section; an exception is Capriccio II, FbWV 502, which concludes at a slow tempo (see Table 3).

5.6 Froberger sometimes demands the utmost variety of tempos. The best example of this is the first fantasia in the 1649 autograph, Fantasia I “Sopra Ut Re Mi Fa Sol La,” FbWV 201 (see Table 4). In this piece, the number of notes per tactus varies between one and sixteen. At the beginning, Froberger writes the famous “Ut Re Mi Fa Sol La” fugue subject with a succession of whole notes accompanied by a countersubject consisting mostly of quarter notes. In m. 23, the fugue subject is written in quarter notes, the motive now moving three times faster. In addition, the subject and its answer appear nearly simultaneously, creating a stretto effect, which further enhances the tempo acceleration. In m. 36, Froberger increases the intuitive tempo even more. Here the speed of the fugue subject itself slows down; it comprises half notes instead of quarter notes. However, the composer provides (and then spins out) a motive in running sixteenth notes to accompany the fugue subject. These continuously moving fast notes create excitement and feel climactic. The return to the mood of the opening duple-meter section occurs suddenly at m. 47; here the music, filled predominantly with half notes, slows down significantly (Froberger could have written here “Adasio”). Fantasia I does not end at this point but moves on to succeeding sections that further show various tempo changes.

6. Tempo Relationships among the Movements of Froberger’s Suites

6.1 For the French-style dance pieces, the tempo relationship (or even the existence of one) between the movements of the suites has not attracted much attention from scholars because it is generally believed that the speed of such pieces is determined by the dance characteristics rather than the notated meter. Reflecting French performance practice in the second half of the seventeenth century, Georg Muffat states that meter does not necessarily connote tempo in dance-style pieces. In the preface to his first volume of Florilegia, Muffat tries to be specific about the speed intended by different time signatures; however, he also mentions that tempo is obedient to the qualities of dance types. He writes, for instance, that 3/2 is used for slow movements and 3/4 for swifter ones, but he goes on to say that regardless of meter, sarabandes are taken slowly and gigues and canaries “the fastest of all, no matter how the measure is marked.”[18]

6.2 French musicians of the seventeenth century were not strictly concerned with tempo relations between dances of different types. They did not expect groups of diverse pieces to create a sense of unity. In many sources for the lute music of the first half of the seventeenth century, for instance, dances are grouped by their types, not in a manner that would later become known as the suite.[19] This practice continued well into the second half of the seventeenth century. Only around the time Jacques Champion de Chambonnières published his first set of keyboard suites (1670)[20] did a definitive sequence of dance pieces start to appear. The earlier tradition did not entirely disappear until much later. A well-known French source that probably dates from the late seventeenth century, containing more than three hundred keyboard pieces, for example, still groups the compositions in the older fashion.[21]

6.3 Froberger presumably visited Paris on multiple occasions and was very well acquainted with French music. He, however, did not exactly follow the French tradition: he valued the unity of grouped dance movements. As early as 1649, he gathered sets of dance movements to create single musical works: in that year he copied six suites into his “Libro secondo” (the second autograph volume dedicated to the Austrian emperor). At this early stage, Froberger was inclined to collect only a small number of dances. Four of the six suites in the 1649 autograph—FbWV 601, 603, 604, and 605—consist of only three movements each: allemande, courante, and sarabande. At the same time, however, Froberger seems to have begun experimenting with a four-movement format by adding a gigue at the end of one suite in that collection, FbWV 602. The remaining suite in the 1649 autograph, FbWV 606, has an alternative opening: a set of variations in the place of an allemande. By the time the composer prepared his “Libro quarto,” the 1656 autograph, he seems to have settled on the four-movement structure comprising allemande, gigue, courante, and sarabande, the sequence he maintained until his death, as evident in the recently discovered autograph apparently prepared in Froberger’s final years.[22]

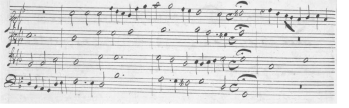

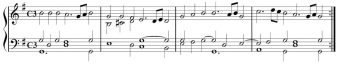

6.4 A close relationship between the movements of Froberger’s suites can be observed in the so-called variation suites. The best example of such a piece is the last work in the 1649 autograph (FbVW 606), in which all movements, including a double to the courante, are based on a single tune called “Mayerin.” A simple, pleasing, and serene melody in binary form appears in the opening section, titled “prima partita.” It is in duple meter and marked C; quarter notes are predominant (see Ex. 2a). The most comfortable speed of these quarter notes is probably at the slower side of the human heartbeat, perhaps around MM=60; thus, the velocity of the tactus alla semibreve is around MM=15. The first reprise of the tune, shown in Ex. 2a, covers only four whole notes—i.e., four tactus. After a series of variations, mostly in the meter C, a courante follows. It is in triple meter marked C3, each tactus alla semibreve comprising three half notes (see Ex. 2b). While the courante is another variation on the “Mayerin” tune, now the first reprise consists of eight tactus instead of four as in the opening movement. If we posit that the duration of the song melody is the same in both movements, then the tactus speed for the courante will be around MM=30, which is twice as fast as that of the previous movement.

6.5 Changing our focus from the level of the tactus to that of the surface pulse—while still positing that the duration of the song melody is the same in the two movements—we see that three half-note beats in triple meter (in the courante) occur in the space of two quarter-note beats in duple (in the “prima partita”). Under those circumstances, if the quarter note of the opening movement is set at MM=60, then the half note of the courante will be at MM=90.[23] This is significantly faster than the likely tempo of the first-movement variations, which must accommodate running sixteenth notes (and in any case are mainly in the meter C). This relationship can also be observed between the first-movement variations and the final movement of the suite, a sarabande marked C3. The “Mayerin” tune here is carried out in a simple succession of half notes, which are indeed the pulse of the movement (see Ex. 3). This suggests that the speed of the pulse is identical in the two triple-meter dances. However, the tempo in the courante would be perceived as much faster because that movement contains a larger number of fast-moving notes such as quarter notes. This is especially true in its double, a variation of the courante.

7. The Relationship between Allemandes and Gigues

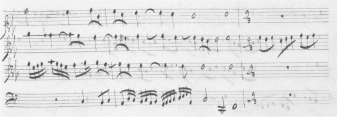

7.1 Another feature that suggests a strong association between movements, in this case adjacent allemandes and gigues, is the discrétion designation that appears at the ending measures of selected gigues. These passages reflect the free and improvisational style found in non-fugal sections of Froberger’s toccatas and other contrapuntal works as well as many of his representative and highly emotional allemandes and allemande-like movements.[24] Only three gigues are marked with the instructive phrase “avec discrétion”: FbWV 607, 613, and 620.[25] At those places where the indication appears, typical dotted gigue rhythms and gigue textures are less apparent; instead, these passages show more allemande-like figures, including a succession of four or more sixteenth notes and broken chords in the style brisé. At the conclusion of the gigue from the well-known Memento Mori suite (FbWV 620), for example, Froberger stops the continuous dotted rhythms and introduces longer note values (see Ex. 4). Here the two successive quarter notes in the lower voices, coupled with a quarter note followed by sixteenth notes in the top line, are typical of the opening movements of Froberger’s suites.

7.2 The discrétion segments of Froberger’s gigues often display a distinctive melodic motive, which consists of two fast-moving notes making a large descending leap, followed in contrary motion by a note of longer value. Froberger seems to have been fond of this distinctive figure, writing it frequently, especially in his allemandes. An outstanding example of this is the first movement of the fifth suite in the 1656 autograph (FbWV 611), in which the opening measures feature a series of statements of the motive in the upper voices (See Ex. 5).

In the gigues, on the other hand, the figure is included less frequently; hence, it stands out when it does appear, possibly making the listener recall the sentiment of the previous movement and thus linking the two movements in the listener’s imagination. In the gigue from FbWV 620, for example, Froberger does not introduce the descending figure until well into the discrétion section. The first appearance of the motive in the melodic line appears near the end of the second measure of Ex. 4 (shown above). It consists of two sixteen notes an octave apart (d″ and d′), followed by a dotted eighth note on g′‑sharp. Two additional appearances are found in the extended final measure of the piece, but they are less visible because they are split between the two upper voices; though disguised in appearance, they are clearly audible. A variant of the motive appears in the second voice, in the middle of the second measure of Ex. 4. It comprises a sixteenth note on a′, two tied dotted eighth notes on d′, a sixteenth note on d′, and two tied quarter notes on g′. These descending figures are indeed abundant, especially near the end of the allemande of the same suite. Note that it was Froberger’s customary practice, evident in his autographs, to place gigues immediately after allemandes, an order no other composer regularly adopted. Perhaps Froberger’s motivation for this was to create unity between the two movements, an aim less achievable if they were located far apart.

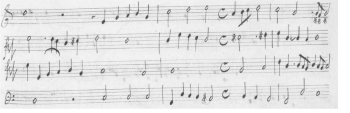

7.3 In addition to the thematic association between allemandes and gigues, Froberger may also have intended their tempos to be closely related. This is evident in the final section of the gigue of the fourth suite in the 1656 autograph (FbWV 610: see Ex. 6). The movement is in compound duple meter marked C3, a time signature rather unusual for Froberger’s gigues but typical in his courantes and sarabandes (as we saw above in Exx. 2b and 3). Near the end, however, the meter changes to simple duple time C to conclude the movement. As David Schulenberg points out, these final measures reflect Froberger’s compositional style in the allemandes: “The ending has the effect of joining the allemande and the gigue into a single larger unit, somewhat like the two halves of a French overture.”[26] Thus, the function of the new meter here is to slow the tempo down from that required for the lively gigue to that of the somber allemande. Froberger often writes this sort of decelerated ending at the conclusion of his toccatas and other contrapuntal compositions. In these places, he writes improvisational, free-style idioms like those in the discrétion endings of some gigues. Incidentally, two of the three gigues marked avec discrétion (FbWV 607 and 613) are also inscribed “lentement.”[27]

7.4 The successive sixteenth notes in the concluding measures of the gigue of FbWV 610 (Ex. 6) require a slower tempo than that of the lively portion of the gigue if they are to be effectively heard. To achieve this, Froberger not only changes the meter but also alters the level of the beat—that is, the surface pulse—from dotted half notes in the main part of the gigue (in C3) to quarter notes in the conclusion (in C). The semibreve tactus of the lively gigue comprises two dotted half notes, but that of the concluding segment, four quarter notes. Yet as we have noted, the tempo of the tactus must necessarily slow down to accommodate the sixteenth notes. If the tempo relationship between the tactus of C3 and C here is the same as in the courante and “prima partita” of the “Mayerin” suite, discussed above—notwithstanding the fact that this gigue is in compound duple meter and that courante is in triple—then the semibreve tactus slows down by about half. In that case the surface pulse of the gigue stays more or less constant—say, MM=48 for the dotted half note in C3 and the quarter note in C. In any case, the effect of the change in rhythms is a deceleration in speed. In the C3 section, the main rhythmic figures comprise either a half note and a quarter note or a dotted quarter note, eighth note, and quarter note. This would make the listener aware of the subdivision of the pulse, which consists of quarter notes moving at perhaps the speed of MM=144. In the C segment, on the other hand, note values smaller than the pulse are rather decorative, and what is most apparent here is the quarter notes moving around the speed of MM=48.

7.5 Among the twelve suites included in the 1649 and 1656 autographs, seven contain gigues. The sole gigue in the 1649 autograph appears at the end of the second suite (FbWV 602), but all gigues in the 1656 autograph are placed immediately after allemandes. Moreover, the majority of those in the 1656 autograph (four out of the six) are written in the meter C, the time signature utilized in all of Froberger’s allemandes. It is not entirely clear why Froberger wrote gigues in simple instead of compound meter; in any case, the effective dance rhythms may be much alike in performance.[28] Perhaps Froberger wanted to emphasize the tempo relationship between the first two movements of his suites. In the allemande and gigue of the third suite in the 1656 autograph (FbWV 609), for instance, a common melodic motive appears throughout these two movements (see Exx. 7a and 7b). The suite as a whole is not a variation suite, but the presence of this thematic figure in more than one dance may suggest that Froberger intended to bring the two duple-meter movements together. If this is the case, the motive should be played in an identical manner. Thus, the speed of the quarter-note pulse as well as the tactus alla semibreve would be the same in the allemande and gigue. The perception of the tempo, however, is different. In the allemande, a series of half notes in the bass creates a feeling of a slow pace. In addition, dotted rhythm, which is often associated with a lively tempo, is less abundant than in the following movement. In the gigue, on the other hand, slow moving notes seldom appear, and the dotted figures clearly identify the quarter notes as a pulsing beat. In short, the gigue would be perceived as a faster movement than the allemande.

7.6 To summarize, Froberger’s suites, especially those in the autographs, include evidence to suggest that the composer may have intended all movements to have close tempo relationships with one another. The surface pulse and/or tactus can be identical between an allemande and a gigue, the first two movements of most suites. The velocity of the beat changes for courantes and sarabandes, the final two dances of most suites. This change is achieved by the shift of meter (duple to triple). The difference in velocity should probably be proportional, the pulse in the last two movements faster by 150% (the mathematical proportion of 2:3). In comparing the first two movements, the perception is that they are different in tempo. Allemandes tend to show a large number of slow notes, while fast-moving notes define the pulse in gigues. The opposite is true between courantes and sarabandes; the listener would feel the former to be much faster than the latter, even if the duration of the tactus remains identical between these movements. In short, Froberger’s allemandes are meant to be the slowest among the movements in his suites; gigues, fast; courantes, the fastest; and sarabandes, at a moderate speed (but faster than allemandes).[29] It was presumably to emphasize this tempo-relation scheme that Froberger placed gigues adjacent to allemandes and wrote both in duple meter.

8. Conclusion

8.1 Froberger may have intended the speed of the tactus or surface pulse to be variable only to a certain extent. On the contrary, he may have wanted to keep the fundamental pulse mostly steady so that his compositions would exhibit unity and coherence. Froberger’s music, however, is far from rigid. He cleverly interweaves various rhythms and rhythmic figures to fluctuate tempos without disturbing the tactus. This is evident especially in Froberger’s strict contrapuntal compositions, which seem to have been written largely within the framework of the traditional proportion system developed in the Renaissance (the quick-moving triple with quarter-note beats being the most obvious modernism). At the same time, however, the idea of strict proportions can also be observed in Froberger’s French-style music. From the point of view of tempo, there is apparently a close relationship between the movements of the suites.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express sincere gratitude to Lois Rosow, who provided me with countless editorial suggestions and comments. I also would like to thank David Schulenberg and Alexander Silbiger for helping me develop this article.

Examples

Ex. 1. Frescobaldi, “Canzon Prima Canto Solo,” mm. 41–45. Frescobaldi, Canzoni da sonare (Venice: Vicenti, 1634).

Ex. 2. Suite in G Major, FbWV 606: a. “Prima Partita,” first reprise; b. Courante, first reprise. Froberger, “Libro Secondo.”

Ex. 3. Suite in G Major, FbWV 606, opening of Sarabande. Froberger, “Libro Secondo.”

Ex. 4. Suite in D Major, FbWV 620, conclusion of Gigue. Sing-Akademie zu Berlin, Musikarchiv SA 4450.

Ex. 5. Suite in D Major, FbWV 611, opening of Allemande. Froberger, “Libro Quarto.”

Ex. 6. Suite in A Minor, FbWV 610, conclusion of Gigue. Froberger, “Libro Quarto.”

Ex. 7. Suite in G Minor, FbWV 609: a. opening of Allemande; b. opening of Gigue. Froberger, “Libro Quarto.”

Figures

Fig. 1. Ricercar V, FbWV 405, beginning of triple-meter section. Froberger, “Libro di Capricci e Ricercati.”

Fig. 2. Ricercar V, FbWV 405, end of triple-meter section. Froberger, “Libro di Capricci e Ricercati.”

Fig. 3. Canzona III, FbWV 303, end of opening section. Froberger, “Libro Secondo.”

Fig. 4. Fantasia V, FbWV 205, end of section in 3. Froberger, “Libro Secondo.”

Fig. 5. Ricercar I, FbWV 401: a. mm. 1–5; b. mm. 16–20; c. mm. 21–25; d. mm. 26–31. Froberger, “Libro di Capricci e Ricercati.”

Tables

Table 1. Successive meters in Froberger’s contrapuntal compositions

Table 2. Compositional plan, Ricercar IX, FbWV 409

Table 3. Compositional plan, Capriccio II, FbWV 502

Table 4. Compositional plan, Fantasia I (“sopra ut re mi fa sol la”), FbWV 201