The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 26 (2020) No. 1

A Tale of Two Cantors: Heinrich Grimm (1592–1637) and Thomas Selle (1599–1663) during the Thirty Years War

Joanna Carter Hunt*

Abstract

The Thirty Years War (1618–48) placed countless musicians in desperate circumstances and greatly altered their career trajectories. While difficulties experienced by court musicians during and after the conflict are familiar from the writings of Heinrich Schütz, the impact of the war on German church musicians has received less attention. This essay compares the biographies of two cantors: Thomas Selle, who thrived in the relatively peaceful Hanseatic city of Hamburg, and Heinrich Grimm, town cantor in Magdeburg, who became a self-proclaimed “musician in exile” in Braunschweig following the destruction of Magdeburg in 1631.

2. Grimm’s Early Life and Work

3. The Effects of the War on Grimm’s Career

4. Selle’s Early Life and Work

5. Selle and the Hamburg Cantorate

1. Introduction

1.1 It was the best of times. It was the worst of times. This “Tale of Two Cantors” considers the careers of Heinrich Grimm (1592–1637) and Thomas Selle (1599–1663), musicians who shaped the music cultures of Magdeburg and Hamburg, respectively, during the Thirty Years War. Although both cantors held similar positions in large cities with significant musical offerings, they experienced the effects of the war quite differently. Magdeburg’s cantor, Heinrich Grimm, suffered the loss of his home and his position when the city was devastated in 1631. Forced to relocate and work as a freelance musician, Grimm eventually found permanent employment in Braunschweig but never regained his former stature as a cantor. Conversely, Thomas Selle enjoyed the many benefits of living in the Hanseatic city of Hamburg, which not only encountered little turmoil during the war, but actually thrived and expanded many of its musical programs throughout the seventeenth century. Although one can merely speculate about Heinrich Grimm’s potential productivity and influence had he not become a musical casualty of the Thirty Years War, a comparison of his career with that of Selle reveals the diversity of experience musicians faced in the seventeenth century, as well as the paradoxical nature of the war itself.

1.2 In general, historians estimate five million civilians perished from various causes during the Thirty Years War, which was about twenty percent of the population in the Holy Roman Empire at the start of the conflict.[1] Indeed, the complex social, religious, economic, and cultural factors that caused and perpetuated the war make it difficult to assess its effects on the German lands broadly speaking. Moreover, the warfare was so widespread that most parts of Europe felt its impact at one time or another. Since combat occurred to varying degrees and at different times across Europe, scholars seeking to examine the war’s impact on the average person gain valuable insights by focusing on the experience of specific individuals within their regional contexts.[2] The destruction caused by the Thirty Years War cannot be understated; yet seventeenth-century church musicians such as Grimm and Selle still managed to compose, publish, and perform works, as well as disseminate printed and manuscripts copies of their pieces. Their divergent career trajectories, to the extent we can reconstruct them, provide clear examples of how individuals encountered and responded to the vicissitudes of the Thirty Years War differently.

1.3 Although Thomas Selle lived about twenty years longer than Heinrich Grimm, the two cantors share similar backgrounds, and their professional lives offer interesting points of comparison. Born in 1599 and 1592, respectively, Selle and Grimm each received musical training at an early age from renowned musicians, who may have furthered their careers. Both came from small villages in central Germany, and may have performed with well-known choirs in their youth before attending university. They held prominent positions in two of the most significant centers for sacred music in Lutheran Germany: Hamburg and Magdeburg.[3] In the early seventeenth century, both cities were similar in size and stature, with Hamburg’s inhabitants numbering about 38,000, and Magdeburg’s population of 30,000 in 1630 being nearly twice that of Leipzig or Dresden.[4] As was common in other Lutheran cities in Germany, Selle and Grimm were responsible for organizing, composing, and presenting the music in their cities’ main churches each week, as well as supervising music education at the local Latin school. In addition, they oversaw all official civic musical performances, from concerts at festivals to music at political events.

1.4 Their instructional duties led the two cantors to produce rudimentary music theory primers that were most certainly used in the classroom. One point of direct intersection between Selle and Grimm concerns a manuscript copy of two manuals owned by the former, who bound his own “Anleitung zur Singekunst” of 1642 together with Grimm’s 1634 monochord treatise, and used both texts to instruct his pupils.[5] Selle’s copy of Grimm’s manual contains his own marginal notes on related sources and general commentaries on the material; likewise, his personal library included various publications of Grimm’s compositions and theoretical writings.[6] It is also noteworthy that Selle used elements from Grimm’s 1629 edition of Johann Walter’s St. Matthew Passion when crafting his own Passion of St. Matthew in 1642.[7] Selle’s obvious appreciation for Grimm’s work attests to the latter’s enduring prominence among contemporaries even after his death. One wonders how far Grimm might have extended his influence as a composer and theorist if his career had not been disrupted by the devastation of Magdeburg.

2. Grimm’s Early Life and Work

2.1 During the seventeenth century, Heinrich Grimm enjoyed some renown as a composer and was often cited as an authority on music theory. Grimm’s pupil Otto Gibelius (1612–82) described him in 1659 as “the eminent musician and composer” and “my highly esteemed and much beloved former music teacher.”[8] Johann Walther noted that Grimm served as the cantor of Magdeburg prior to its destruction and that he wrote various theoretical works.[9] Johann Mattheson viewed Grimm as one of the most significant proponents of solmization after Seth Calvisius (1556–1615) and a famous musician and composer of his time.[10] Indeed, Grimm was often linked in print with several well-known musicians, namely Michael Praetorius, Seth Calvisius, Heinrich Baryphonus, and Johannes Lippius.[11]

2.2 Relatively few documents concerning Grimm’s early life survived the Thirty Years War, but it is possible to glean some information from publications and extant materials.[12] Born into a large family in 1592 in the village of Holzminden, Grimm presumably showed some musical talent at a young age.[13] He eventually came into contact with Michael Praetorius (1571–1621), who in 1604 began serving as Hofkapellmeister for Duke Heinrich Julius in nearby Braunschweig, and received further musical training from him. In the preface to volume 5 of the collection Musae Sioniae (1607) Praetorius identified Grimm as the composer of one of its motets, calling him “my fourteen-year-old pupil.”[14] It is noteworthy that Praetorius apparently supported the boy’s education, given Grimm’s lack of means and the former’s demanding professional obligations. In 1609 Grimm began studying philosophy (and probably theology as well) at the University of Helmstedt.[15] Within eight years, Grimm was appointed as cantor of Magdeburg’s principal churches and Altstadt Gymnasium, a prestigious first position.[16] It is not clear whether Praetorius, who was also concurrently engaged as Kapellmeister for the administrator of the bishopric in Magdeburg, had any role in securing the position for his former pupil, but Grimm may well have benefited from the association.[17]

2.3 Between 1617 and 1631, Grimm’s cantorial duties involved instructing the fourth- and fifth-grade pupils of the Altstadt School in music, and organizing the music at Magdeburg’s two main churches, St. Johannes and St. Jacobi. His responsibilities expanded in 1619, when he also began leading his pupils in performing contrapuntal choral music once a month in the cathedral.[18] During this period Grimm published a number of anthologies for both school and church use, as well as most of his extant theoretical works. His compositions include a variety of genres of seventeenth-century Lutheran church music, such as motets, concerted sacred works for two and three voices, and chorale arrangements. Grimm, whose musical style is often compared to that of Johann Hermann Schein (1586–1630), wrote idiomatically for instruments and typically provided alternative scoring options in his compositions. Indeed, the cantor has been credited with introducing basso continuo works to Magdeburg, incorporating figured bass in many of his pieces prior to 1624.[19] Moreover, it is noteworthy that a large number of Grimm’s compositions appeared in anthologies along with those of contemporaries such as Schütz, Calvisius, Baryphonus, Schein, and Scheidt.[20] The fact that Grimm is designated as musicus instead of cantor in a published motet from 1618, Ach Herr, straff mich nicht, probably indicates that Grimm was regarded early in his career as an accomplished musician and composer.[21]

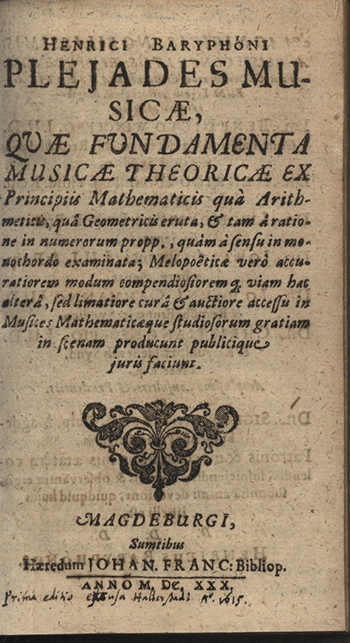

2.4 By 1619, Grimm had established himself in Magdeburg personally and professionally. That year his predecessor as cantor, Friedrich Weißensee, composed an eight-voice motet to honor his marriage to Martha Brand, which included an original text based on an anagram of the name Henricus Grimmius.[22] In addition to cultivating relationships with important figures in Magdeburg at this time, Grimm exchanged letters with the cantor of Quedlinburg, Heinrich Baryphonus, whose significant theoretical treatise Pleiades Musicae (originally published in 1615) he edited and expanded in 1630 (Figure 1).[23] Grimm may also have had contact with Schütz and Scheidt through their possible involvement in reorganizing the music at Magdeburg’s cathedral.[24]

2.5 In general, Grimm seemed to be enjoying “the best of times” in Magdeburg prior to its siege and destruction in 1631. He was an active composer, teacher, and theorist, who had established his reputation as a musician beyond the boundaries of Magdeburg. Over eighty extant compositions by Grimm were published between 1618 and 1631, as well as all of his surviving printed theoretical works.[25] His Latin monochord treatise and the now-lost German translation mentioned by Grimm’s pupil Konrad Matthaei may also have been written during his tenure in Magdeburg.[26] According to the inscription on the decachord Grimm crafted to accompany his manuscript monochord manual, the instrument was initially designed in 1630 and later enhanced after the cantor relocated to Braunschweig.[27] Since the two pedagogical tools were certainly intended to be used together, as the markings on the decachord also imply, it seems probable that the monochord treatise was drafted, or at least conceived, prior to 1631.

3. The Effects of the War on Grimm’s Career

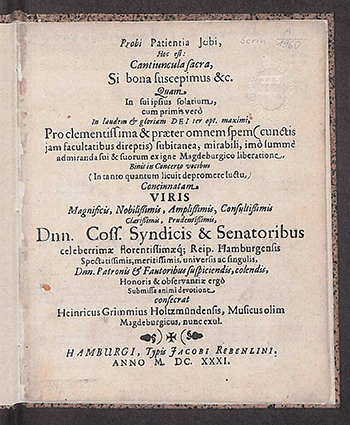

3.1 The destruction of Magdeburg by imperial troops in May 1631 was one of the defining events of the Thirty Years War due to the city’s image as a center of Lutheran Protestantism, as well as the extensive loss of life and property. As the historian Hans Mednick has noted, contemporary accounts portray it as the most controversial and catastrophic occurrence of the war, with over 200 pamphlets and numerous broadsheets and newspaper articles covering the event in 1631.[28] During the massacre and conflagration, two-thirds of Magdeburg’s population died, and many others, such as Heinrich Grimm, fled the city. In fact, a census from February 1632 showed only 449 inhabitants living in Magdeburg.[29] Fortunately, Grimm and his family were able to escape the “Magdeburger Bluthochzeit” (Sack of Magdeburg) with the help of a Jesuit priest.[30] Although no records have remained that document the family’s journey following their flight, archival evidence indicates that Grimm worked on a freelance basis in Hamburg during 1631.[31] During his stay, Grimm also published a short concerto for two tenors and basso continuo, Probi Patentia Jobi, which he dedicated to the Hamburg City Council the same year (Figure 2).

3.2 The work’s title page includes the usual adulation of the Council one would expect, yet it also reveals Grimm’s status as a self-proclaimed “musician in exile” (“Henricus Grimmius Holtzmündenʃis, Muʃicus olim/ Magdeburgicus, nunc exul”). Perhaps Grimm hoped his dedication—as well as the music itself—would evoke sympathy for his troubles and secure a position in the politically stable city of Hamburg, or simply result in some remuneration for his efforts. Unfortunately, the publication did not prompt the Council to reward Grimm with a formal employment offer, so he was forced to consider other options. The apt text of Probi Patentia Jobi on the sufferings of Job, paraphrasing Job 2:10 and 1:21, certainly mirrors the plight of the composer himself:

| Si bona suscepimus de manu Domini, | If we have received good things from the hand of God, |

| Mala autem quare non sustineamus? | why should we not also endure bad things? |

| Dominus dedit, Dominus abstulit: | The Lord has given, and the Lord has taken away. |

| Sicut Domino placuit, ita factum est | Just as it has pleased the Lord, so has it been done. |

| Sit nomen Domini benedictum. | Blessed be the name of the Lord. |

Although the text’s fatalistic message ends in praise of God, the first line (from verse 2:10; my translation) was typically associated with funeral music, an allusion that was probably not lost on the City Council.[32] Following the setting, Grimm includes a canon on Luther’s text Verleih uns Frieden gnädiglich, Herr Gott, zu unsern Zeiten (Mercifully grant us peace, Lord God, in our time), which serves to underscore the broader impact of the war and the need for divine intervention.

3.3 Grimm’s tenure in Hamburg must have been brief, for his arrival in Braunschweig was noted in court documents in 1631 as well. He was given a “friendly reception” by Duke Friedrich Ulrich; however, no position at court was forthcoming.[33] It is possible that Grimm relocated to Braunschweig in part because a close friend from his university days, Conradt Huhstedt, was serving as the cantor at St. Martini Church in Braunschweig. Given the friendship with Huhstedt, who published one of Grimm’s collections posthumously,[34] it is even more surprising that Grimm’s audition in September 1631 for the cantorate at St. Katharinen Church was unsuccessful.[35] Throughout 1631, Grimm worked as a freelance composer and musician at various Braunschweig churches, including St. Martini and St. Michaelis.[36] When the organist at St. Andreas Church died the next year, however, Grimm assumed the position and held it until shortly before his own death in 1637. In addition to his role as organist, Grimm continued to teach and compose; in fact, two of his later collections of concertos were published in 1635 and 1636.[37] One concerto from the now-lost 1635 collection, Lobet den Herren alle Heiden, which survives in manuscript sources,[38] provides an example of Grimm’s sacred concerto style (Audio Example 1). It also appears that Grimm had not given up the hope of serving as cantor, nor holding a similar position at court. In late August of 1634 he presented a manuscript copy of his monochord treatise to the designated successor to Duke Friedrich Ulrich, August II (August the Younger). The manual, dedicated to Duke August, was later bound together with Lippius’s Synopsis Musicae Novae (1612) and became a part of the extensive ducal library. Although the inclusion of the volume in the duke’s impressive collection was alone surely an honor for Grimm, the dedication did not lead to another permanent position.

3.4 Although Heinrich Grimm experienced “the worst of times” in the latter part of his career, he still managed to provide for his family as an organist and produce further compositions, as well as participate in the music culture of Braunschweig, including mentoring his pupils Otto Gibelius and Konrad Matthaei, both of whom went on to work as cantors and theorists. His own son Michael, who collaborated with Conradt Huhstedt in publishing Grimm’s Vestibulum Hortuli Harmonici sacri (1643) posthumously, received training from his father and also served as a court organist in neighboring Celle. The devastation of Magdeburg, which robbed Grimm of his professional stability and resources, certainly affected the cantor’s output in terms of the number and types of works he composed. Moreover, the change in his pedagogical duties, moving from a formal classroom setting to private lessons, seems to have caused a reduction in the number of theoretical texts he produced. At the very least, Grimm’s extant music publications drop significantly after his relocation to Braunschweig. It is also possible that many of Grimm’s earlier works that were due to be published in Magdeburg by printer Andreas Betzel were lost when the city went up in flames. Fortunately, in his thematic catalog of Grimm’s works compiled in 2000, Thomas Synofzik nearly doubles the number of pieces previously attributed to the cantor by locating works transmitted in manuscript sources and others lacking title pages.[39] Nevertheless, the war clearly contributed to the loss of sources and made the process of identifying his extant works more difficult.

4. Selle’s Early Life and Work

4.1 As with many aspects of Thomas Selle’s career, the state of his extant works is quite different from Grimm’s owing to the stability of Hamburg during the war. Selle compiled his own manuscript set of 281 sacred compositions and upon his death bequeathed it to the St. Johannis School, where he had been teaching. Along with his entire library of pieces and texts by other musicians, over 300 sacred and secular works by Selle were eventually transferred from the school to their current location in the Hamburg State Library.[40]

4.2 Like Grimm’s, Selle’s early life and education remain somewhat obscure.[41] The preface to Selle’s Opera omnia, along with archival materials written before the cantor’s Hamburg tenure (1641–63), aid in reconstructing his background.[42] Born in Zörbig on March 23, 1599, Selle spent his youth in the small town, located about twelve miles northeast of Halle. It is likely that Selle became a pupil at the Leipzig Thomasschule by the age of sixteen. He appears to have worked under Seth Calvisius and Johann Hermann Schein there,[43] prior to matriculating at the University of Leipzig in the summer term of 1622. While it is unclear what subjects Selle studied at the university, he may well have pursued advanced training in Latin since he was responsible for teaching the language to his Latin school pupils and he also composed Latin verses for some of his musical works.[44]

4.3 In contrast to Heinrich Grimm, Selle held various posts with increasing levels of responsibility in northern Germany before becoming Hamburg’s cantor and civic music director in 1641. When Selle accepted his first position in 1624, as a tutor at a school in Heide, at least one original polyphonic work had already been published.[45] Additional publications followed in 1624, including two collections of three-part secular vocal works, as well as a few compositions for weddings.[46] Despite calling the pieces in his collections “the works of a beginner,” Selle appears to have been highly regarded by his colleagues in Heide, as indicated by the various Latin verses contributed to the two volumes in his honor.[47]

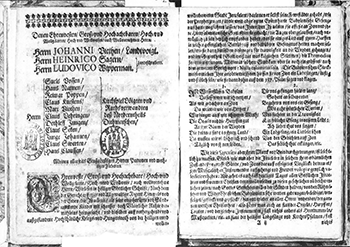

4.4 One year later, Selle relocated to nearby Wesselburen, where he worked for nine years as a school rector. During his tenure, the region was not directly embroiled in combat, but its residents experienced the effects of the war, especially famine, plundering, and the plague.[48] In his first collection of sacred works, printed in 1627 (Figure 3), Selle likened the local tribulations he was witnessing to the suffering of the exiled Israelites described in Psalm 137:

Also gehet es auch fast heutiges Tages allen Geistlichen Jsraeliten vnd frommen Christen denn weil dieselben zu diesen gefehrlichen vnd beschwehrlichen zeiten nach Gottes Gerechten willen der Sünden halben von den Röhmischen vnd WiderChristlichen Babyloniern sehr werden gedrungen beleidigt verfolget gestöckt vnd gepflöckt hin vnd wieder an allen Orten vnd enden.… Also höret man auch an statt der Orgeln Harpffen Lauten vnd dergleichen Jnstrumenten fast nichts anders als Heertrummeln Mußquetten etc. an statt der heiligen Lobgesänge vnd KirchenPsalmen fast nichts anders als Heulen Winseln vnd Wehklagen.

(Thus nowadays it is happening in this way to all clergy, Israelites, and devout Christians, for in these dangerous and difficult times, according to God’s righteous will, they are hard pressed, insulted, persecuted, maimed, and repeatedly impaled in all places and ways on account of the sins of the Roman and unchristian Babylonians.… Instead of the organ, harps, lutes, and such instruments, one hears almost nothing other than military drums and muskets. Instead of holy songs of praise and psalms, almost nothing other than wailing, whining, and lamenting.)[49]

Other German composers of the era express similar complaints in prefatory material to their collections.[50] In keeping with the constraints Selle must have experienced due to the conflict, he composed numerous works for small ensemble in the 1630s that were certainly shaped by the limited musical resources available in Wesselburen.[51]

4.5 While serving as school rector between 1625 and 1634, Selle established a lifelong friendship with the Lutheran pastor and poet Johann Rist (1607–67). Their professional collaborations yielded numerous settings of Rist’s poetry.[52] The year Selle died, Rist described one of Selle’s eight-voice compositions after hearing it performed in church:

Der Herr Director deß Musikalischen Chores/ mein alter mehr als dreissig-jähriger Freund/ Herr Sellius, mit dem vollem Chor/ unser schönes/ aber von ihm noch viel schöner in die Music versetztes Kirchenlied: Warum betrübst du dich mein Hertz/ anfieng zu musicieren/ wodurch ich widrüm dermassen ward erquicket/ daß mich dauchte/ ich wäre gleichsam neu gebohren/ ich aus der Kirche wiederum so freudig zu Hause ging, als wenn alle meine Trübsale wären verschwunden.

(When the director of the choir, my old friend of more than thirty years, Mr. Selle, and the entire choir began to perform our beautiful hymn, set even more beautifully by him to music, I was so refreshed by it that I thought I was reborn. I went home so happily from church, it was as if all my sorrows had disappeared.)[53]

Selle’s setting must have indeed been popular, since it appears as part of a musical prelude to “Vom Lauff der Welt,” a text used for oratorical practice at a Gymnasium in Nordhausen.[54]

4.6 In February 1634, the city officials of Itzehoe, located forty-two miles northwest of Hamburg, invited Selle to audition for the position of cantor. It is likely they were familiar with Selle and his work, since the preface to the cantor’s “Monomachia harmonico-latina,” part 2, confirms that the 1630 collection was completed in Itzehoe four years prior to Selle’s audition.[55] On March 2, 1634, Selle was offered the position officially, and he relocated two months later.[56]

4.7 At least five anthologies, two containing secular works and three devoted to sacred pieces, appeared within the next two years. As cantor, Selle may have finally had the means to publish works he had composed earlier in Wesselburen. Despite the increased responsibilities of his new position, Selle published more of his compositions during his shorter, seven-year tenure in the Itzehoe cantorate.

5. Selle and the Hamburg Cantorate

5.1 On August 12, 1641, Selle became cantor of Hamburg’s Latin school, one of the most prominent positions a Lutheran church musician could hold in the 1600s.[57] Besides being one of the most populous cities in seventeenth-century Germany, with resources available to support a vibrant musical culture, Hamburg generally escaped the atrocities of the Thirty Years War. A port city and member of the Hanseatic League, Hamburg enjoyed certain financial advantages over other German cities. An additional reason for the city’s economic stability during the war, however, was its policy of neutrality towards other European powers. Moreover, Hamburg’s leadership had authorized the construction of a formidable wall in 1618 as the war was beginning. The security afforded by these measures led many affluent refugees to relocate to Hamburg in the early seventeenth century, which engendered even greater wealth in the city.[58] While there were many opportunities for musicians to perform secular music during this period of growth, the most significant developments occurred in church music in the first half of the seventeenth century. The fact that most of the city’s churches had to expand or build new choir stalls and galleries for instrumentalists between 1600 and 1630 attests to the rise of sacred music performance in Hamburg at the turn of the century.[59]

5.2 In addition to his teaching duties at the St. Johannis School, Selle composed and led the service music in Hamburg’s four main churches and the cathedral. While serving in Hamburg, Selle’s compositional output included over two hundred pieces, mainly sacred vocal works written for liturgical purposes.[60] Selle’s Johannespassion (1641/43), regarded as the first oratorio Passion performed with instrumental interludes, is probably his most famous work.[61]

5.3 Scholars have observed stylistic similarities between the music of both Schein and Michael Praetorius and Selle’s own eclectic musical style.[62] Selle’s traditional cantus firmus concerto settings, as well as his freely constructed concertos incorporating Italianate elements reflect the influence of Schein. Likewise, Selle’s use of instrumental sections to articulate clear vocal forms, alternating performing forces, and polychoral techniques evoke works by Praetorius.

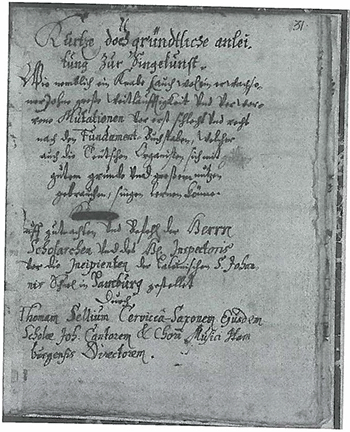

5.4 The cantor was responsible for music instruction in grades one to eight at the St. Johannis School. The pupils studied rudimentary music theory under Selle and his assistants, as well as choral music. Training in contrapuntal vocal music in particular was essential, as the pupils were called to perform musica figuralis in Hamburg’s main churches on a regular basis.[63] Moreover, in order to improve the quality of performances in Hamburg, Selle devoted himself early in his tenure as cantor to developing the musical skills of his pupils and wrote his own music primer, “Kurtze doch gründtliche anleitung zur Singekunst,” in 1642 (Figure 4).[64]

5.5 A letter from January 1642 documents the cantor’s formal appeal for ten well-trained singers to perform concerted music (four discant singers and two on each of the other parts), sixteen singers for motets, and singers from the orphanage to supplement the pupils of the Latin school and the Gymnasium for works requiring large musical forces.[65] Moreover, the town council granted Selle’s request to employ a permanent group of eight singers and furnish them with room and board. The Cantorei, as the group was called, aided Selle with copying scores, rehearsing with younger singers, and performing music. Selle outlined detailed protocols for both the Cantorei and the instrumentalists performing liturgical music, along with more stringent guidelines for his pupils, as multiple letters written between 1642 and 1650 reveal.[66] Selle’s elaborate rules specify what benefits and food items the professional singers should receive, and how they were to conduct themselves.[67] To maintain continuity, the singers had to serve in the Cantorei for at least one year.[68] In other letters to the Ministry for the city’s churches, however, the cantor expressed his frustrations with the professional choristers and the city instrumentalists, who often disrupted church services after imbibing in the tavern during the sermon.[69]

5.6 Selle’s attention to every detail of his proposed plan to improve and expand Hamburg’s musical offerings clearly reveals his dedication as a cantor and musician. It also underscores the fact that resources were available to him in the city of Hamburg. As a cosmopolitan city with the financial means to attract musicians in a secure environment, Hamburg provided Selle with many opportunities to create large-scale sacred works, such as his Passions and other occasional pieces. For example, to celebrate the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, Selle composed a setting of Psalm 150 (Lobet den Herrn) for four choirs and as many as twenty-two parts, including various instruments (Audio Example 2).[70] Celebrations marking the end of the war took place in Hamburg in October 1648 and September 1650. Chronicles describe the event in 1650 in detail, documenting the texts used for the three sermons and the music that was presented.[71] Selle’s festal music, mounted first in the St. Petri Church and later in the afternoon in St. Nicolai, was “gloriously sung and performed.”[72] Throughout the day starting at 10:00 in the morning, trumpets were heard from multiple church towers. During a fireworks display between 7:00 and 10:00 in the evening, verses from a song by Johann Rist celebrating the peace alternated with trumpet and drum interludes.

5.7 Selle had the good fortune to work alongside many talented musicians in Hamburg. In addition to the well-known organists Jacob Praetorius, Heinrich Scheidemann, and Matthias Weckmann, he collaborated with the leader of Hamburg’s city instrumentalists Johan Schop in performing liturgical music. Hamburg had a greater number of Ratsmusikanten than any other German city, which Selle used to his advantage to compose more technically demanding works for larger ensembles. In compiling his Opera omnia, Selle also updated various early works to include additional optional instrumental parts and separate choral forces, an indication that Hamburg’s ample musical resources allowed him greater creative freedom.[73]

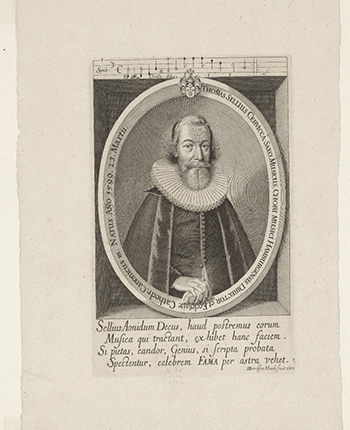

5.8 Ten years before Selle’s death in 1663, the artist Dirk Dircksen fashioned a copper engraving of the cantor, describing him as “the ornament of the Muses,” whose renown “reaches the stars” (Figure 5).[74] Another music aficionado, Kunrat von Hövelen, described Selle and the music culture of Hamburg in the mid-seventeenth century in glowing terms. In particular, he names Scheidemann, Selle, and Schop as three of the “most excellent” musicians there have ever been, and proclaims that this is known by distant strangers, as well as city inhabitants.[75]

6. Conclusion

6.1 It is unfortunate that Heinrich Grimm never enjoyed a comparable level of renown, despite his many professional accomplishments. One wonders how Grimm’s career might have unfolded if the Thirty Years War had not caused his circumstances to change so dramatically, or even if he had relocated to Hamburg instead of Braunschweig after the devastation of Magdeburg. As his pupils and other contemporaries confirm, Grimm’s musical talents garnered the respect of his peers well into the eighteenth century, and his publications continued to appear regularly in book fair catalogs. In contrast to Thomas Selle, Grimm produced more music theoretical texts, which distinguished him as a greater authority on such matters, and he attained professional prominence earlier in his career. Despite Grimm’s broader skill set and comparable compositional talents, he slipped into relative obscurity, while Thomas Selle did not. Today, we have no pictures of the Magdeburg cantor, and few modern editions and commercial recordings of his music. Sadly, Heinrich Grimm’s tale and experience are not unique among many musicians during the Thirty Years War. Indeed, other ill-fated composers of the period, like Heinrich Grimm, whose important musical contributions are still largely unavailable or unknown, should be identified and their works brought to light.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Jürgen Neubacher, Head of the Special Collections and Music Divisions of the Hamburg State and University Library, and Dr. Thomas Synofzik, Director of the Robert Schuman House, for their help in obtaining materials during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figures

Figure 1. Heinrich Baryphonus, Pleiades Musicae …, expanded edition

Figure 2. Grimm, Probi Patientia Jobi

Figure 3. Selle, Hagio-Deca-Melydrion, voice part II, preface

Figure 4. Selle, “Kurtze doch gründtliche Anleitung zur Singekunst”

Figure 5. Dirk Dircksen, copper engraving of Thomas Selle

Audio Examples

Audio Example 1. Grimm, Lobet den Herren alle Heiden / Es wollt uns Gott genädig sein

Audio Example 2. Selle, Lobet den Herrn in seinem Heiligthum