The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 30 (2024) No. 1

Ottavio Rinuccini’s Narciso: A Study and Edition

Tim Carter*

Abstract

The role of poet Ottavio Rinuccini (1563–1621) in creating the “first” operas cannot be disputed: his Dafne (music by Jacopo Corsi, Jacopo Peri, and perhaps Giulio Caccini), Euridice (Peri and Caccini), and Arianna (Claudio Monteverdi) created essential models for the form and content of subsequent librettos. He failed, however, with Narciso, which may have been intended for performance around the time of the wedding of Duke Ferdinando Gonzaga and Caterina de’ Medici in Florence in early 1617, or possibly sooner (in its first version, at least) in a convent. After Rinuccini’s death, Monteverdi said that the poet was fond of the text and had asked him to set it to music. The composer also admitted that he could not see a way to make it work because it lacked variety, it raised serious problems in terms of casting, and it had a “tragic and sad” ending. The obvious questions are: Where did Rinuccini go wrong, and why? The answers perhaps lie not just in the poetry—presented here in a new critical edition from a rarely acknowledged source—but also in problems with the genre itself.

4. Narcissus, Echo, and the Power of Cupid

1. Introduction

1.1 On 1 May 1627, Claudio Monteverdi wrote to his former collaborator Alessandro Striggio (the younger) about yet another commission for theatrical music to be done in Mantua. The idea had first emerged in early January 1627, probably arising from the recent accession (October 1626) of Vincenzo II Gonzaga and his investiture as Duke of Mantua in February 1627. These types of requests had begun not long after the composer was released from Mantuan service in 1612, and although he was now ensconced in the prestigious position of maestro di cappella at St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, a combination of obligation and necessity forced him to keep responding to them in helpful ways even as he often came up with creative excuses to avoid any real commitment.[1]

1.2 The present case was no different. Monteverdi noted that Striggio might be sending him a theatrical text to set to music but insisted that it be in “an excellent style” and that he should be given plenty of time to complete the work. He also offered Striggio two settings of passages from Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata that he had already composed: one of the Armida and Rinaldo episode (from Canto 16), and the other, “the fight between Tancredi and Clorinda” (Canto 12). His Armida setting does not survive, but the Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda had been performed in the residence of the Venetian patron Girolamo Mocenigo in Carnival 1624 (it was later published in the Madrigali guerrieri, et amorosi, his Eighth Book of madrigals, in 1638). Monteverdi also made another suggestion: “a little play by Signor Giulio Strozzi, very beautiful and unusual, which runs to some 400 lines, called Licori finta pazza innamorata d’Aminta, and this—after a thousand comic situations—ends up with a wedding, by a nice touch of stratagem.”[2]

1.3 Given Duke Vincenzo’s rather problematic situation over his own illicit marriage (in 1616) to Isabella di Novellara, a comedy ending with a wedding might not have been the most diplomatic of ideas: he and Isabella were forcibly estranged, although their union was (re)validated in April 1627. But Striggio seems to have been interested enough in Strozzi’s play to ask Monteverdi to send a copy, which he did by the next mail, on 7 May. The composer also included in that letter another possible text:

But to give further proof of my heartfelt affection (even though I know for sure that the task would be more difficult for me), I am sending you the enclosed Narciso, a work by Signor Ottavio Rinuccini, which has never been printed, nor set to music by anyone, nor ever performed onstage.[3] This gentleman, when he was alive (how fervently I pray that he is now in Heaven!) did me the favor not only of giving me a copy but also of asking me to take it on, for he liked the work very much, and hoped that I might have [an opportunity] to set it to music.

I have had a go at it several times, and turned it over to some extent in my mind, but to tell Your Most Illustrious Lordship the truth, it would not, in my opinion, succeed so powerfully as I would wish for, because of the numerous sopranos we would have to employ for so many nymphs, and the numerous tenors for so many shepherds, and nothing else by way of variety. And then a sad and tragic ending! However I did not want to neglect sending it so that Your Most Illustrious Lordship could look it over and give it the benefit of your fine judgment.

1.4 In Monteverdi’s next letter (22 May), it emerges that Striggio had sent back the copies of La finta pazza (so Monteverdi now called it) and Narciso—they were the only ones the composer had (so he had written on 7 May)—and had decided in favor of Strozzi’s text, also providing instructions on how it might best be fashioned for a performance in Mantua. Monteverdi (or at least Strozzi) kept working on it through the summer, although Striggio appears to have decided to drop the project in September (so it seems from Monteverdi’s letter of the 18th of that month).[4] Monteverdi was probably relieved, given that he had now taken on a much more ambitious project to provide music for the festivities in Parma for the wedding of Duke Odoardo Farnese and Margherita de’ Medici (which eventually took place in December 1628). His Armida setting remained in play, however: on 2 October 1627, Monteverdi promised to have a copy made; he handed it over to the copyist in mid-December (so he told Striggio on the 18th); and the composer’s colleague and friend, the singer Giacomo Rapallini (sometimes styled Rapallino), sent the score to Mantua on 19 February 1628.[5]

1.5 It is revealing that Monteverdi felt enough obligation to Rinuccini to suggest Narciso to Striggio long after the poet’s death on 28 March 1621. This was not the only poetry by him that Monteverdi had kept in mind for possible musical treatment: he included in his Madrigali guerrieri, et amorosi (1638) two first-time settings of verse that dated back several decades (we do not know when the music was composed). One of them, Ogni amante è guerrier: nel suo gran regno, drew on a text (adapting Ovid’s “Militat omnis amans” in Amores, I.9) that Rinuccini had dedicated to Jacopo Corsi, who died in 1602. The other was the ballo, Volgendo in ciel per immortal sentiero–Movete al mio bel suon le piante snelle, which combined two sonnets, the first of which, at least, was intended to celebrate a birthday of King Henri IV of France (assassinated in 1610).[6] Both of those texts were adapted fairly easily to replace any reference to the French monarch with mentions instead of the intended dedicatee of the Eighth Book, Emperor Ferdinand II (although he died in 1637, so Monteverdi switched the dedication to his son Ferdinand III). But clearly, Narciso was causing Monteverdi greater headaches. As he wrote to Striggio on 7 May 1627, he had grappled with it on multiple occasions and had somewhat digested it in his mind (“Holle datto più volte assalti, e l’ho alquanto digesta nella mia mente”)—this is quite forceful language—but he could not get anywhere with it.[7]

1.6 Monteverdi’s negative criticisms of Narciso may or may not have been another delaying tactic typical of his dealings with Mantua, offering something with one hand while taking it away with the other. But they were couched in terms that Striggio would have recognized full well given that they echoed quite precisely the complaints that the composer had made ten years earlier—in a series of letters from December 1616 and January 1617—when the Mantuans presented him with another problematic dramatic text: Scipione Agnelli’s Le nozze di Tetide.[8] This also required too many sopranos and tenors, he wrote (on 29 December 1616); the dialogues and, in particular, the soliloquies were too long; and the work lacked opportunities for musical and vocal variety. Striggio had agreed with Monteverdi then, just as he seems to have done about Narciso a decade later. These were common problems in theatrical texts intended for musical setting, and Striggio had no less sense than Monteverdi of what could or could not be made to work onstage given what they had achieved separately and together in the text and music of the composer’s first opera, Orfeo (1607).

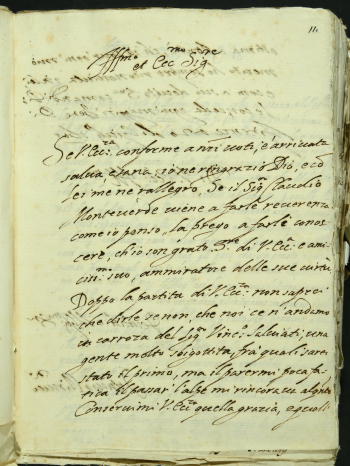

1.7 Agnelli was a well-meaning amateur, however, and Monteverdi probably hoped for something far better from Rinuccini, given the evident success of their collaboration on the opera Arianna, performed in Mantua on 28 May 1608 as part of the festivities celebrating the marriage of Prince Francesco Gonzaga and Margherita of Savoy. This was something of a hit: other performances were planned for Florence in early 1614 and in Mantua in April–May 1620; and the composer revived it in Venice in Carnival 1639–40. Monteverdi had also set another theatrical text by Rinuccini—the Ballo delle ingrate (also for the 1608 Mantuan festivities)—as well as other of his lyric poetry. As for Rinuccini, he certainly seems to have enjoyed working with the composer. On 20 June 1615 (see Fig. 1), he wrote to his patron and friend, Don Giovanni de’ Medici (the legitimized son of Grand Duke Cosimo I and uncle to the current grand duke), who had just arrived in Venice (he subsequently became Commander-in-Chief of the army of the Republic). Here Rinuccini expresses his hopes that the journey went well, but then turns quickly to make a very specific request:

If, as I expect, Signor Claudio Monteverde comes to pay his respects, I beg you to make him know that I am the grateful servant of Your Excellency, and his very great friend [and] admirer of his abilities.[9]

But despite the mutual regard between the poet and the musician, and for all that Rinuccini greatly liked Narciso, so Monteverdi wrote in 1627 (“amando egli molto tal sua opera”), his libretto was always going to be troublesome for the stage.[10]

1.8 Rinuccini’s pride in his libretto is clear also from the fact that he mentions it along with his Dafne in a long semi-autobiographical (it seems) narrative ode: he connects these two works in other ways as well, we shall see (in par. 3.12–13 and 4.4).[11] Modern scholars have tended to agree with Monteverdi, however. They praise the “lyric” qualities of Narciso but admit its many dramatic failings.[12] They also note the apparent paradox of a text that denies the power of love intended for a genre that customarily celebrates it in some manner or other, plus the fact that it lacks the emotional range or reversals that any musical setting might require.[13] However, these later comments appear largely to have been based just on reading one version of the libretto rather than on any notion of how it might have been created and for whom, or what might have been done to it had a composer taken it in hand. The present essay does not seek to redeem Narciso from its patent flaws, but it does provide a more detailed account of its sources than has been available to date, and likewise the most comprehensive edition of Rinccini’s text.[14] It also attempts a more nuanced reading of these materials to suggest how and why those flaws arose.

2. Manuscript Sources

2.1 We do not know how the manuscript of Narciso kept by Monteverdi might have related to the two that survive (a known third is now lost). The earliest is Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Barb. lat. 3987 (henceforth V),[15] which also appears to reflect another musician’s interest in the text: a note on the flyleaf says that this “dramma originale” was donated by Cavaliere Loreto Vittori to Cardinal Francesco Barberini. Vittori (1600–1670) was a prominent castrato, composer, poet, and playwright who sang in both Florence and Rome, and who had been named by Pope Gregory XV a “Cavaliere della Milizia di Gesù Cristo” sometime before 30 August 1622 (when the title starts appearing in documents). He was in Florence probably from 1619 until the death of Grand Duke Cosimo II de’ Medici in late February 1621, and he sang the role of the Archangel Gabriel in a set of “versi sacri” by Rinuccini performed in the private chapel of Archduchess Maria Magdalena of Austria in the Palazzo Pitti on the Feast of the Annunciation in 1620.[16]

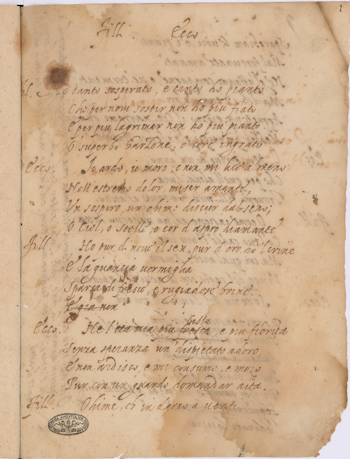

2.2 V can be connected directly to Rinuccini by virtue of its two clear layers. The first (V1) presents a complete version of the text in an elegant hand, probably by a copyist that we find in other Rinuccini manuscripts: the original foliation (1–23) is clearly apparent (see Fig. 2). At some point, Rinuccini himself then revised the text (V2), making annotations in his own hand both on the original pages of V1 and then, when this became too cumbersome, by inserting new leaves, with the result that V now spans fols. 1–32.[17] The expansion in V2 was quite significant (around 300 lines of verse), and it involved the addition of new scenes and characters, as well as revising and extending the text that had already been written.

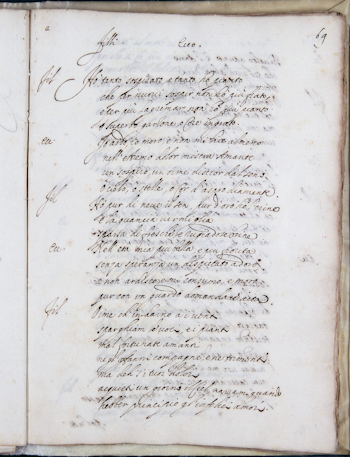

2.3 At some point, someone (Loreto Vittori?) went through the entire manuscript noting minor things that needed to be checked, including the assignment of speeches where no character had been indicated.[18] But even in its “final” form, V appears incomplete: it does not have the strophic chorus one would expect at the end (we shall see [par. 4.9] that this lack could be significant). Other omissions include an initial list of “Interlocutori” (the list of characters) and a prologue. However, a character-list and prologue are present in the second copy of Narciso (called at the head of the list a “favola”), inserted into Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Magliabechiano VII.902 as fols. 66r–92v (henceforth F), preceding other poetry by Rinuccini.[19] F presents the two layers of V as a unified text (in a single hand, but not Rinuccini’s), also with some significant variants but still without a final chorus (see Fig. 3). This manuscript was copied in 1640, it seems, and would appear to be associated with the prominent Florentine literati Jacopo Soldani (1579–1641) and Andrea Cavalcanti (1610–1673), who may have wanted in some way to preserve the work of their distinguished predecessor.[20]

2.4 The different readings of Narciso in F make it clear that it was not copied directly from V (or any exact copy thereof). We can no longer tell how it might have related to the copy (reportedly autograph) in the Biblioteca Trivulziana (Milan), appended to the beginning of Cod. Triv. 1005, the first of two manuscripts that Rinuccini seems to have prepared as an authoritative collection of his poetry (the other was Cod. Triv. 1006): both manuscripts in Milan were lost during or shortly after World War II.[21] The character-list and prologue present in F (but absent in V) were also in Cod. Triv. 1005, but we have no other indication of their similarities or differences. However, there are certainly some important variants between the readings in F and V, most of which would count as improvements. They were presumably generated in one or more additional manuscripts of the text that must have existed but are now lost, including the one that Rinuccini presented to Monteverdi. Certainly, it seems very unlikely that someone other than the poet would have bothered to make these kinds of changes after his death.

2.5 In contrast to his other librettos, Rinuccini never published Narciso during his lifetime (another sign that it was never performed); nor did his son, Pierfrancesco, include it in the posthumous edition of the poet’s works that he brought out in early 1623. Indeed, the text only came to light again when Luigi Maria Rezzi (1785–1857), director of the Biblioteca Barberiniana (containing the private library of Cardinal Francesco Barberini), published an edition in 1829 based on V.[22] Angelo Solerti then included it in his own edition of Rinuccini’s librettos that formed the second volume of his Gli albori del melodramma (1904). Solerti does not seem to have been aware of F, but he certainly consulted Cod. Triv. 1005 (from which, he notes, he derived the character-list and the prologue) even though his reading otherwise matches Rezzi’s (from V) save for his own errors or editorial adjustments. Indeed, Solerti appears to have relied entirely on Rezzi’s edition for the text (other than the prologue), given that he reproduces its mistakes and occasional inventions that cannot have come from any source. The loss of Cod. Triv. 1005, however, means that it is now impossible to determine where its version of Narciso sat between V and F. One might hope that if Cod. Triv. 1005 had indeed contained some or all of the significant revisions in F, then Solerti would have noticed them. But whatever that case, his edition of Narciso (henceforth S) has thus far been treated as the principal version of the text, and therefore the basis of most critical comment on it.[23] Nevertheless, there are strong arguments in favor of any critical edition of Narciso treating the improvements in F as furnishing the “best” text, despite the manuscript’s date (1640) and its current lack of any direct connection to Rinuccini himself. This is the approach adopted here in Appendix 1, which for the first time makes available Narciso in its most refined form.[24]

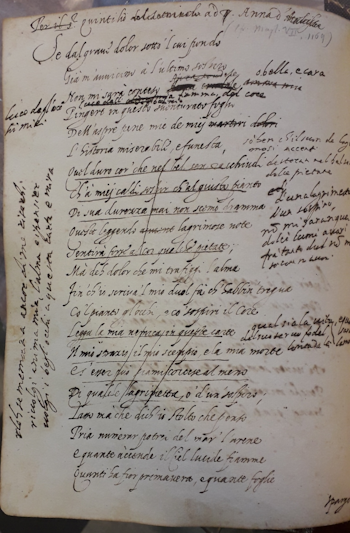

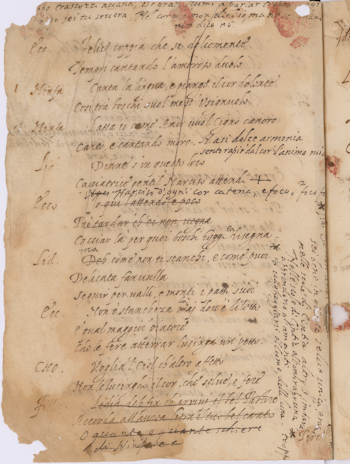

2.6 Whether or not F (edited in Appendix 1) should be preferred to V (followed by Rezzi and Solerti, with some errors), no one thus far has taken the time to decipher the separate layers of V that are conflated in Rezzi’s and Solerti’s editions—that is, the non-autograph V1 and the autograph V2—despite the fact that these two layers reveal a great deal about Rinuccini’s working methods. Indeed, the presentation of Narciso in the two layers of V looks very similar to other surviving manuscripts of Rinuccini’s poetry, including Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Palatino 249 and 250 (the major surviving repositories of his lyric works). For the most part, his standard handwriting is fairly distinctive (compare his letter to Don Giovanni de’ Medici given as Fig. 1), even if it varies according to the nature of his quill, the speed at which he was writing, and the care he took over it. Thus, in Palatino 249–50, it is easy to distinguish poems written directly by Rinuccini from those in more elegant hands (probably various copyists that the poet used regularly, although one or more of these hands may be Rinuccini’s himself in a more formal vein). Most directly relevant to the present argument, however, are those texts in one or other elegant hand with often extensive revisions (Fig. 4 provides a good example). Most, but not all, of these revisions are in Rinuccini’s standard hand, identical to what appears in V2. Similar revisions also appear in poems initially copied directly by the poet: he fussed continuously over his work.

2.7 Palatino 249–50 are very tricky to sort out in codicological terms.[25] The two layers of V are much more straightforward, although they reveal a similar process of (re)writing. For V2, Rinuccini went back over the initial version of the complete text in V1, revising individual words or interleaving additional lines when it could be done on the page or in the margins, and marking others for deletion. All these changes are in his standard hand. There came a point, however, where there were too many to indicate in this manner: hence the insertion of additional leaves and also, where necessary, Rinuccini’s recopying of text from V1 before continuing with the new version. Compare Fig. 6 with Fig. 5: the extensive revisions to V1 and subsequent additions forced Rinuccini to recopy the text from the top of fol. 4v.

2.8 Three further things are also clear. First, the manuscript from which V1 was copied itself had gaps, most notably the end-of-“act” choruses (see par. 4.8), but also incomplete lines. One is apparent in Fig. 2, at the end of Filli’s second speech. This has three lines rather than the four-line pattern that has been established thus far, but here the copyist of V1 began a fourth line (E già non) and did not finish it, perhaps because Rinuccini had not yet decided how to complete the thought with a word rhyming with vermiglia.[26] Second, V2 became in effect a working manuscript; Rinuccini made some alterations in the course of writing it (for example, where he started writing a line of verse but then changed his mind), in addition to making further revisions at some later stage. Third, he still needed to submit the whole text to a further editorial review to remove some of the rough joins and repetitions caused by his insertions.[27] The version of Narciso in F suggests that this was done in (or prior to) a manuscript that was its source, solving some, but not all, of the problems while making revisions and additions to other parts of the text. There are at least two lost manuscripts in which this could have occurred: Cod. Triv. 1005 (if Solerti was not paying attention), and the one kept by Monteverdi. There could well have been others.

2.9 What we find in V1 plus V2 also seems to have been typical of how Rinuccini’s opera librettos came together. In the case of his first, Dafne, he began with a short text (192 lines plus a 20-line prologue) commissioned by the Florentine patrician Jacopo Corsi, probably in 1594, “to make a simple test of what the music of our age can do.”[28] This was set to music by Corsi himself, who then brought the composer Jacopo Peri into the project. The libretto was then put “in better form,” so Rinuccini said (417 lines plus 28 lines for the prologue), for the performance before Grand Duchess Christine of Lorraine and Cardinals del Monte and Montalto in the Palazzo Pitti on 21 January 1599 (modern style), for which we have a poorly printed libretto. Rinuccini then had the libretto printed again in a more elegant format sometime in mid-1600, noting on the title page the fact that it had been performed before the grand duchess. Only fragments of the music survive. There was another performance in the Palazzo Pitti in October 1604 (for which left-over copies of the 1600 edition were provided with a new title page), and the libretto was expanded still more (552 lines plus a 32-line prologue) for a new setting by Marco da Gagliano performed in Mantua in late February 1608 (the libretto was not printed, but Gagliano’s score was published in October).

2.10 We do not have any manuscript materials for Rinuccini’s second opera, Euridice, performed on 6 October 1600 during the festivities celebrating the forthcoming marriage of Maria de’ Medici and King Henri IV of France. Rather, there is a printed libretto (726 lines plus a 28-line prologue), plus two separate scores, one by Giulio Caccini (published in December 1600) and the other by Peri (February 1601). Music by both composers was used in the October 1600 performance, but Peri’s score seems to be closest to what was done on the stage, given that it contains a significant number of revisions to the text, as well as some additions (seven lines of verse). Rinuccini and Peri could plausibly have made them during rehearsals when particular production problems came to light; they are not, on the whole, apparent in Caccini’s score.[29]

2.11 The case of Arianna (1091 lines plus a 24-line prologue) done in Mantua in May 1608, is less straightforward given that although the libretto was printed and reprinted, Monteverdi’s music does not survive save for the Lamento d’Arianna, which circulated quite widely.[30] We do know, however, that Eleonora de’ Medici, Duchess of Mantua, found an early version of Rinuccini’s libretto to be “rather dry” and agreed with the poet that it should be enriched with some action (“di arrichirla con qualche azione essendo assai sciutta”); his additions probably included the initial entry of Venere and Amore (just under 130 lines), and perhaps Arianna’s lament (some 120 lines depending on where and how that insertion was made), as well as the appearance of deities in the finale.[31] Those additions disrupted Rinuccini’s original plan for a five-part design on the Classical model as he had adopted for Euridice, with five episodes (they probably should not be called “scenes” or “acts”), each ending with a strophic chorus:[32] Arianna ended up with six end-of-episode choruses.[33] Such additions could also create different kinds of dramatic difficulties: for example, the “added” lament in Arianna is odd, given that Arianna’s actions during it have already been narrated by a Nunzio (Messenger) in terms of what had taken place offstage. We shall see (par. 6.5) that the expanded Narciso has a similar problem with one of its messengers.

2.12 Even without those new elements, Arianna was a long text.[34] Indeed, the increasing length of Rinuccini’s first three librettos (from the first version of Dafne at 192 lines to the final one of Arianna at 1091, excluding their prologues) is striking. This also took Arianna well beyond the “ideal” length for any libretto recommended by Emilio de’ Cavalieri in 1600 (not exceeding 700 lines).[35] It may be significant that the only libretto that Pierfrancesco Rinuccini included in the posthumous edition of his father’s Poesie (1622/23) was Euridice, which was the most classically balanced of them. But the expanded Narciso is even longer still (1205 lines in V and 1198 in F, plus a 36-line prologue), although its first version (V1) was somewhere between Euridice and Arianna (around 900 lines), and there is some evidence that it may have been shorter still: a series of numbers on the last written page of V1 suggests that the text originally had 758 lines (and thus was more or less the same length as Euridice), although that shortest version cannot now be reconstructed.[36]

2.13 It is clear from Dafne (its three iterations), Arianna (the added material), and even Euridice (the revisions in Peri’s score) that Rinuccini tended to start out with relatively compact treatments of his proposed librettos that then got revised and expanded, whether on literary grounds (before any musical setting came into play) or in response to requests from a composer or patron (or both) in light of an intended performance. Narciso never got to that final stage: Monteverdi said, and Vittori implied, that it had never been set to music, and Monteverdi’s comments on the libretto suggest that it would have benefited greatly from the advice of a composer.

2.14 We cannot yet know why Rinuccini chose to expand V1 by way of V2 (but I have a suggestion; see par. 3.13), or on what literary or other grounds he might have considered V2 to be an improvement, although it (and therefore F) certainly seems better geared toward a potential staging. Nevertheless, the impact of Rinuccini’s revisions was significant, at least in the case of the first three episodes (Solerti calls them “acts,” but our numbering coincides). He inserted three new scenes in V2 (I.3, II.1, III.2) and significantly expanded two more: I.2, with the argument between Eco and Lidia, and II.2, to include Narciso’s dance-song (see Table 1 and the outline of the action in Appendix 2).[37] The final two episodes (Solerti’s Acts IV and V) remained relatively unchanged, although we shall see (par. 4.9) that Rinuccini may have left some space for an alternative ending.

2.15 Those insertions also involved adding two new male characters, Elpino and Nunzio Primo, and significantly expanding the role of a chorus of hunters (Coro di Cacciatori) separate from the chorus of nymphs (Coro di Ninfe) that predominates in V1. Monteverdi’s complaint about not just the number of female singers that Narciso would require (“the numerous sopranos we would have to employ for so many nymphs”) but also the male ones (“the numerous tenors for so many shepherds”) was a result of Rinuccini’s additions in V2: V1 had just Narciso and a single Nunzio (named Tirsi by the chorus), plus a fairly inactive Coro di Cacciatori as Narciso’s companions. This expanded cast was not so different from the one for Arianna as it was performed in Mantua in 1608: its male characters included Teseo, his Consigliere, a Primo and Secondo Nunzio (the latter named Tirsi) plus a Messaggiero, and a Coro di Soldati separate from the (male and female) Coro di Pescatori.[38] The cast in V1, however, was unusually slanted toward female roles (Filli, Eco, Lidia, Amarilli, and all those other nymphs). One might plausibly ask why.

3. Date and Place?

3.1 Scholars have tended to assume, probably correctly, that Narciso was the fourth and last of Rinuccini’s full-scale opera librettos, following Dafne, Euridice, and Arianna. But there is no direct evidence of the date when it was written other than the fact that the surviving prologue was to be delivered in person by the Florentine singer and composer Giulio Caccini, whose death on 10 December 1618 provides a terminus ad quem; this probably also means that at some point, Rinuccini thought that Caccini would write the music for the opera. However, the indirect evidence of its intended purpose has not been properly considered thus far.

3.2 Obviously, the poet must have given, or sent, Monteverdi a copy of the libretto, coupled with his request to consider it for musical setting, at some time before his death in March 1621.[39] We do not know whether Rinuccini (in Florence, although he spent significant amounts of time in France) and Monteverdi (from 1613, in Venice) were in the same place at the same time other than during the creation of Arianna for Mantua in late 1607 and early 1608.[40] However, on 20 January 1617, Monteverdi told Alessandro Striggio that he had received a “very warm-hearted letter” from Rinuccini advising him to come to Florence on the occasion of the festivities to celebrate the marriage of Caterina de’ Medici and Duke Ferdinando Gonzaga (which took place on 7 February). Monteverdi explained the attraction of Rinuccini’s offer:

For indeed I shall be seen not only by all the nobility, but also by the Most Serene Grand Duke himself, and besides the Mantuan wedding we are speaking of, others too are expected, so I would therefore enjoy going; and he more or less indicated that I would be employed on some musical task …

Monteverdi does not say when he got that letter from Rinuccini, nor why he turned down the invitation. His wording is also ambiguous: Rinuccini wants the composer to “transferire a Firenze,” which could mean either visit or make a more permanent move. But his reference to “other” marriages being expected in Florence demands further thought.

3.3 The prologue associated with Narciso in F (and in Cod. Triv. 1005) is unusual given that it is delivered not by some historical, allegorical, or mythical character, as with Ovid in Dafne, La Tragedia in Euridice, and Apollo in Arianna. It is doubly so because in it, Giulio Caccini starts out by presenting a fairly complete summary of his illustrious career, including his birth in Rome (in fact, Tivoli) and training in Florence; the fame he gained by singing before Duke Alfonso II d’Este in Ferrara and then the Pope; and how, back in Florence, he brought to illustrious stages the voices of Alba (Aurora in Il rapimento di Cefalo), Orpheus (in Euridice), and Apollo (in Dafne).[41] Caccini then speaks directly to Christine of Lorraine, now the dowager Grand Duchess of Tuscany:[42]

Per gioia tua, benché dagl’anni stanco, o sostegno e splendor d’Arno e Loreno, note più care ancor trarrò dal seno, cigno canoro più, quanto più bianco. Mentre alle regie tue superbe nuore vie più sacra armonia Pindo riserba, odi, Donna immortal, come tra l’erba un misero fanciul cangiossi in fiore. (For your delight, though I am wearied by years, / o sustainer and splendor of the Arno and Lorraine, / more precious notes will I still draw from my breast, / still more a singing swan, the whiter my hair. // While for your royal, proud daughters[-in-law] / Pindar reserves yet more sacred harmony, / listen, immortal lady, to how amid the grass / a wretched youth could be changed into a flower.)[43]

Here, Caccini is represented as being old (with white hair, singing as a swan reportedly does when close to death); he died at the age of 67. Trickier issues are raised, however, by his reference to the grand duchess’s superbe nuore (plural).

3.4 One would expect any prologue to make some reference to the occasion for which the work is to be performed. And Christine of Lorraine certainly gained a proud daughter-in-law (nuora) on the marriage of her eldest son, Cosimo de’ Medici (later Grand Duke Cosimo II) to Maria Magdalena, Archduchess of Austria, in October 1608. This is probably why Angelo Solerti suggested that Narciso was intended for the festivities celebrating that wedding (see par. 3.16). But a single nuora does not account for the prologue’s plural nuore, and indeed, none of the grand duchess’s other sons was close to marrying prior to Rinuccini’s death (and none did thereafter).[44] Thus, the absence of potential daughters-in-law forces a broader reading of the word nuore (sometimes adopted in the period) as daughters who become brides, and Christine of Lorraine had four of them: Eleonora (b. 1591), Caterina (b. 1593), Maria Maddalena (b. 1600), and Claudia (b. 1604).

3.5 This explains Monteverdi’s reference in January 1617 to the “other” marriages that he was told by Rinuccini were in the offing in addition to the one between Caterina and Ferdinando Gonzaga (“ché oltre alle presenti nozze di Mantoa ancora altre se ne sperano”). Protracted negotiations for Eleonora (and for a time, Caterina) to marry King Philip III of Spain had been dragging on since the death of the king’s first wife, Margaret of Austria, in October 1611, although the grand duchess finally accepted their failure in September 1617, and then briefly pursued the idea of marrying Eleonora to Ferdinand II, King of Bohemia (and later Emperor)—Archduchess Maria Magdalena’s brother—whose first wife, Maria Anna of Bavaria had died in March 1616. However, Eleonora was taken ill and died soon after (on 22 November 1617).[45] Claudia’s case was more straightforward: her marriage to Federico Ubaldo Della Rovere, Prince (later Duke) of Urbino, had been in the cards since 1609, if not before, and the prince visited Florence in October 1616 to cement their match—they married in 1621, when she was seventeen years old, and Federico, sixteen.[46] Maria Maddalena was in a sadder situation. She, too, was proposed as a potential bride for Ferdinand II, but her chances of marriage were limited by virtue of the fact that she was physically handicapped (storpiata): in 1619 she declared her intention to enter the Monastero della Crocetta, which she did in 1621.[47] Rinuccini’s invitation to Monteverdi was correct, however: in the second half of 1616, there were indeed four marriages of Medici princesses in prospect, although only one was scheduled for the immediate future, that of Caterina de’ Medici to the Duke of Mantua, and only one other, Claudia’s, was secure pending her reaching an appropriate age.

3.6 Caterina and Ferdinando’s wedding was somewhat clouded by the embarrassment of the duke’s secret marriage (in February 1616) to his lover, Camilla Faà di Bruno—their son was born in December—which needed to be dissolved in order for him to find a more appropriate wife to secure the Mantuan succession. The timetable also meant that events were squeezed into the last days of Carnival: Duke Ferdinando arrived in Florence on 5 February 1617 (a Sunday), and the wedding ceremony was held in the Duomo on the 7th (Tuesday).[48] Given that Lent began the next day, subsequent entertainments were necessarily subdued save for a grand calcio in Piazza S. Croce on 12 February (another Sunday, which permitted some freedom from Lenten restrictions). Moreover, and somewhat unusually, the main theatrical performance of the festivities took place before, rather than after, the actual wedding: on Monday 6 February, Andrea Salvadori’s spectacular veglia, La liberazione di Tirreno ed Arnea, autori del sangue Toscano, was staged in the Teatro degli Uffizi, with music chiefly by Marco da Gagliano.

3.7 In this light, Rinuccini’s enthusiastic invitation to Monteverdi to come to Florence may also have been an attempt on the part of the poet to rescue his position there. His earlier career had been distinguished enough, given the prestigious stagings of his Dafne and Euridice. He also gained significant favor from Maria de’ Medici and Henri IV on subsequent visits to France (Henri named him a gentilhomme de la Chambre du roi). However, Rinuccini was sidelined during the wedding festivities for Cosimo de’ Medici and Maria Magdalena of Austria in 1608, in part because of the desire to avoid what were considered to be mistakes made in 1600. He had better fortune in Mantua, probably due to the support of Cardinal Ferdinando Gonzaga: Marco da Gagliano’s new setting of his Dafne was performed there in late February 1608, and Rinuccini and Monteverdi’s Arianna (staged on 28 May during the festivities celebrating the marriage of Prince Francesco Gonzaga and Margherita of Savoy) was a distinct success. But after Cosimo de’ Medici became grand duke in 1609, the winds changed. Rinuccini’s last major work to be staged in the Palazzo Pitti was the Mascherata di ninfe di Senna (5 May 1613), the commission for which probably came directly from Grand Duchess Christine, given that it served to celebrate the marriage of her very distant cousin, Renée de Lorraine, to a member of the lesser Tuscan nobility, Mario II Sforza, Count of Santa Fiora.[49] A few months earlier, however, Rinuccini had been forced to share the stage with other, younger Florentine poets in providing texts for a grand tournament and mascherata performed on 17 and 19 February, including Jacopo Cicognini (1577–1631) and Andrea Salvadori (1588–1634).[50] Salvadori, newly returned to Florence following his studies at the Collegio Romano, soon fell busy making a name for himself as the chief poet for Medici entertainments: his contributions to those for the visit of Federico Della Rovere in October 1616 included an elaborate festino da ballare in the Palazzo Pitti on the 12th and then the grand balletto a cavallo, Guerra di Bellezza, in Piazza S. Croce on the 16th. They led directly to Salvadori’s gaining a formal appointment from the Medici (on 23 October 1616) with a salary of 16 scudi per month.[51] It is not at all surprising that he was chosen to provide the veglia for the wedding of Caterina de’ Medici and Ferdinando Gonzaga.

3.8 Rinuccini must have known that his star was on the wane. When Dafne was performed on 9 November 1611 in the residence of his old friend and patron, Don Giovanni de’ Medici, he wrote an unusually explicit prologue:[52] La Musica laments the fact that while she had once been allowed to represent the glories of Apollo, Orpheus, and (in one version of this prologue) Ariadne under royal roofs, she has now been banished from them by a mob that she does not deem worthy of naming (Turba, di cui ridir non degno il nome, / tolsemi ogni mio pregio, ogni mio vanto). As a result (ll. 29–32):

E poteo sì che dal reale albergo, ove d’or mi credea rinnovar gli anni, per sottrarmi d’invidia a’ fieri inganni, volsi, sdegnando, disprezzata il tergo. (And so powerful [was the mob] that from the royal dwelling / where I once believed I would renew the ages, / in order to distance myself from the harsh stratagems of jealousy, / did I, scorned, turn my back in disdain.)

Nevertheless, La Musica now hopes to have found a warmer welcome under the auspices of the “sun of the most worthy knights” (o sol de’ cavalier più degni) who has so generously chosen to welcome her into his house.

3.9 Don Giovanni de’ Medici (b. 1567) was four years younger than Rinuccini;[53] Christine of Lorraine (b. 1565) was between them in age. They were all now part of an older generation. However, if that performance of Dafne served to continue the poet’s relationship with a prominent male member of the Medici family, there were also ways in which he could still cultivate the support of the principal Medici women as well. Another new prologue for Dafne (so Solerti suggests), of unknown date, is delivered by Apollo. The god has descended from high Olympus on a fiery chariot to enter a humble cloister so as to pay homage to a still brighter sun (dentr’umil chiostro a venerar discendo / un sol di me più degno e più lucente), an exalted queen born into a most august family (Germe d’eccelsi Augusti, alta Regina).[54] He then urges her to heed what follows (ll. 13–16):

Senti quai note poi, quai dolci accenti di pure verginelle escon dal petto, mentre a colmarti il sen d’almo diletto empion di bel furor le caste menti. (Hear then what notes, what sweet accents / come from the breast of pure virgins, / while to fill your bosom with nourishing delight / they fill their chaste minds with fine passion.)

Clearly this performance prefaced by Apollo was to be given in a convent by one or other group of its female residents (pure verginelle), which begs the question of how any male roles in it were to be performed; in the 1599 version of Dafne there are only two—Apollo and the Nunzio describing Dafne’s metamorphosis, plus the chorus of nymphs and shepherds.[55]

3.10 A similar venue is suggested by a prologue that Rinuccini wrote for an otherwise unknown performance in Florence of Arianna by cloistered “convertite,” possibly in the convent of S. Elisabetta delle Convertite (in the Oltrarno).[56] Here La Sapienza (Wisdom) says that she has come from Olympus to this holy cloister beloved of Heaven (in questo sacro al ciel diletto chiostro); that she will inflame the breast with holy ardor (Di sacro ardor per infiammarvi il petto) to reveal a heavenly secret (occulto arcano rivelar del Cielo); and that although the audience will hear the wretched lament of a royal bride abandoned at the seashore, they will also learn how a mind can be changed, and crown and kingdom scorned to aim for higher things (Come cangi desio, come poteo / sprezzar, sereno il cor, corona e regno).[57]

3.11 There is plenty of evidence for the performance of “theatrical” entertainments in Florentine convents—both for their communities and for select visitors—and some had the personnel, resources, and facilities to do so on a relatively ambitious scale. Despite the prevalence of sacre rappresentazioni, with or without music, drawing on the lives of female saints or the like, the repertory could be quite wide and even, at times, somewhat secular in its inclusion of mythical figures on the one hand, and comic elements on the other.[58] Indeed, one of the more popular sacre rappresentazioni in sixteenth-century Florence, La rappresentatione di Santa Uliva, featured the tale of Narcissus and Echo prominently in one of its intermedi (done to some form of music, apparently).[59] Arianna might still seem an odd choice for such a location, especially given the nature of its plot—the eponymous heroine has eloped with Theseus only for him to abandon her in Naxos—although it is not entirely inappropriate for “convertite” (that is, women of ill-repute who have “converted” to mend their ways). The work also has a quite large number of male characters (see above). But as La Sapienza says, there is a moral to be drawn from the tale: Ariadne is eventually rescued from her despair by Bacchus, who takes her into the heavens, proving, so Ariadne says, that blessed is the heart which has a god for comfort (Beato è il cor che ha per conforto un Dio). Bacchus’s final comment makes the point clearer still, emphasizing the glorious reward for those who scorn mortal beauty out of heavenly desire (gloriosa mercé d’alma che sprezza, / per celeste desio, mortal bellezza).[60]

3.12 The story of Daphne, devoted to the hunt and therefore to Diana (by implication in the 1599 text and explicitly in the 1608 one), is yet more decorous: she transforms into a laurel so as to resist the amorous advances of Apollo (made lovestruck by Cupid), and therefore becomes exalted as a model of chastity. Narciso, too, brings Diana and Cupid into the frame: we shall see (par. 4.4 and 4.6) that in it Rinuccini makes explicit reference both to the Daphne story and to his telling of it in his first opera libretto. He seems to have felt that the stories of Daphne and of Narcissus and Echo were two sides of the same coin, revealing the dangerous powers of love that might best be denied by those seeking beatitude on a more spiritual plane.

3.13 There are other features shared between Dafne and Narciso as well. The first version of the latter (V1) is similar to the 1599 Dafne in terms of its principal roles (just two male ones: Narciso and a Nunzio, the latter named Tirsi): from that point of view, if some version of Dafne could be done by pure verginelle in a convent, the first version of Narciso would have been even better suited to such performers given its chorus made up predominantly of nymphs. The revisions in V2, however, took Narciso beyond the convent, as it were, if that was its original destination. Indeed, the fact that V2 came closer to the final version of Arianna in terms of casting suggests that Rinuccini now had his eyes on a more public forum: that Narciso could also be part of a wedding celebration for one or other of the grand duchess’s nuore. But in the case of Caterina de’ Medici’s marriage to Ferdinando Gonzaga, Rinuccini’s chief competitor, Andrea Salvadori, got the prize instead.

3.14 Both Grand Duchess Christine of Lorraine and Archduchess Maria Magdalena of Austria necessarily—by virtue of their gender and their responsibilities—supported Florentine convents and particular events therein; the grand duchess was particularly renowned for her spiritual devotion to them.[61] If Rinuccini originally intended Narciso for that purpose, it would certainly have kept him in Christine’s favor. She was directly associated with Dafne by way of its performance in the Palazzo Pitti in January 1599, and she is directly addressed by Giulio Caccini in the prologue to Narciso. Maria Magdalena may also have kept Rinuccini in mind: his last known works are various sets of “versi sacri” to be performed in the archduchess’s chapel in the Pitti in Easter 1619 and for the Feast of the Annunciation in 1620 (when Loreto Vittori sang as the Archangel Gabriel).[62] But while the original Narciso might have worked well enough in such a context, its expansion left much to be desired.

3.15 Rinuccini invited Monteverdi to come to Florence around the time of the wedding of Caterina de’ Medici and Ferdinando Gonzaga, and he sweetened the deal by saying that the composer would be involved in “some musical task.” In 1627, Monteverdi said that in the case of Narciso, the poet hoped that the composer “might have [the opportunity] to set it to music” (“sperando ch’io l’avessi a porre in musica”), a wording that implies the offer of some kind of commission. It is hard to resist the suggestion that Rinuccini’s invitation and Monteverdi’s receiving a copy of Narciso are somehow connected.[63] But Monteverdi would probably have had a similar reaction to it then as he did a decade later concerning its troublesome casting and its “sad and tragic ending.” Of course, the ending was neither sad nor tragic in any religious context, and anyway, it was determined by the myth on which Narciso is based. Rinuccini could have found a solution to it, however, even if the sources suggest that he did not yet know what it might be.

3.16 It is true, however, that save for the terminus ad quem for the prologue (Caccini’s death), there is no secure evidence for the dating of the first version of Narciso (V1) or the second (V2). Solerti associated the work with the unspecified “commedia” by Rinuccini that was planned for the festivities celebrating the marriage of Prince Cosimo de’ Medici and Maria Magdalena of Austria in October 1608 but never came to fruition.[64] It is hard to pin that down any further, however. The fact that a sonnet by Rinuccini written in 1609 mentions his other librettos but not Narciso does not necessarily mean that it came later (given that it had not been staged).[65] But situating the libretto somewhere in the 1610s, and the revised version (and the prologue) specifically in 1616–17 remains a guess, though not an entirely uneducated one.

4. Narcissus, Echo, and the Power of Cupid

4.1 Rinuccini plays somewhat fast and loose with the Narcissus myth despite his obvious source: Ovid’s Metamorphoses, 3.339–510. Ovid uses the Narcissus tale as an example of the powers of prophesy granted by Jupiter to the blind Tiresias, who told the naiad Liriope that the son born to her and Cephisus, Narcissus, would live to a ripe old age provided “he does not discover himself.” At age sixteen, Narcissus is so handsome as to be desired by many youths and maidens, but he is too proud to welcome their attentions. One nymph in particular, Echo, catches sight of him hunting and falls enamored. But as Ovid explains, Echo already had a handicap imposed during a previous altercation with Juno: she could not speak in full sentences but only echo the last words said to her.[66]

4.2 Ovid recounts how Echo pursues Narcissus through the fields but is hampered by her vocal impediment, and when she reveals herself to the youth, he rebuffs her violently. Rejected, she wanders the woods alone and wastes away, leaving only the sound of her voice. Meanwhile Narcissus continues to scorn the affections of other nymphs of the rivers and mountains, and also the company of young men. One of those (men, Ovid suggests) who had been mocked by him then caused Rhamnusia (Nemesis) to heed his plea: that Narcissus should fall in love but fail to command the object of his affections. As Narcissus is resting by a spring, tired by the heat and his exertions in the hunt, he sees his reflection in the water: Ovid then engages in a typically luxurious description of how Narcissus is entranced, speaks to his image, and tries to touch and kiss it, all in vain. He, too, wastes away—observed by a pitying Echo—and when the naiads and dryads come to take his body to his funeral pyre, they find only a flower in its place.

4.3 As for turning this tale into an opera, it would hardly be appropriate for its main female character, Eco, to be verbally inarticulate from the outset. For dramatic reasons, too, Rinuccini needed to weave more tightly together the strands of the Echo and Narcissus stories that Ovid largely kept separate save for that moment of rebuff. Thus, he shifts the blame for Eco’s transformation to Narciso himself, both as a result of his rejection and, it seems, consequent upon a curse prompted by his effrontery at her advances: that she should never be loved by anyone.[67] Trickier questions were raised, however, by the issue of who should be the cause of Narciso’s own downfall. For Ovid, it is one of his (male) companions who calls upon Nemesis to punish him, whether out of jealousy or from being rudely rejected: the homoerotic overtones are obvious, as they are, too, in Narcissus’s self-adoration. In his oft reprinted translation of the Metamorphoses in ottava rima (first published in 1561), Giovanni Andrea dell’Anguillara removed the ambiguity and had an unnamed nymph appeal to Astrea for justice in the face of Narcissus’s refusal to love her and her companions.[68] When Giambattista Marino recounted the Narcissus story in his Adone (1623; 5.16–28), it is the spurned nymphs as a group who call upon Cupid to punish the youth for the same behavior. However, Marino drew a specific point from the outcome: that heaven therefore enabled Echo to gain her revenge.

4.4 Rinuccini makes Amore (Cupid) the agent of Narciso’s fate, too, but not as a result of a direct call for vengeance by any nymph or shepherd. In his mind, the story of Echo and Narcissus was a close parallel to the one of Apollo and Daphne (from Ovid, Metamorphoses, 1.438–567). In both cases the pesky god seeks to make a demonstration of his authority and power; he punishes Apollo for boasting that his weapons (which killed Python) were more powerful than Amore’s; he does the same to Narciso for his refusal to reciprocate Eco’s affections. In Rinuccini’s second (1599) version of Dafne, the strophic chorus at the end of its second episode (“Nudo Arcier che l’arco tendi”) makes the comparison clear: Amore has just been arguing with his mother, Venere (Venus), about his need to teach Apollo a lesson, and the chorus recounts the story of Narcissus as an example of what the god can do when driven to anger. The same point is made in Narciso; here the chorus at the end of Episode I, “Poscia ch’in fiera guerra,” recounts the story of Apollo and Daphne, which Narciso is failing to heed.[69]

4.5 Eco could not be treated in quite the same manner as the eponymous heroine of Rinuccini’s first opera, however. In that chorus in Dafne, the nymph is but part of a broader narrative (it is Narcissus’s appalling treatment of her that spurs Cupid into action); the same is true of Daphne in the Narciso chorus. In their myths, both Daphne and Echo become disembodied objects: Daphne as a laurel, and Echo, merely a voice. But while Daphne’s metamorphosis is a model of chastity on the one hand, and clarity of purpose on the other (she resists Apollo’s advances because of her devotion to the hunt), Echo’s is based on more dubious grounds. Thus, Rinuccini brings to the stage in Narciso a divine figure who is only behind the scenes in Dafne: Diana—and not as a conventional dea ex machina but, rather, as one capable of making her own exacting demands. Eco and her female companions—and for that matter, the male hunters in whose footsteps they follow—have ostensibly devoted themselves to the goddess, although Narciso’s beauty is causing all the nymphs to waver in that regard. Eco is particularly duplicitous, however, because she publicly proclaims her chaste fidelity to Diana both to her companions and to Narciso while secretly harboring, and then acting upon, her decidedly unchaste feelings for him. In her first appearance in Narciso (II.4), Diana warns the collective nymphs against the perils of love, from which no good can come. In her second (IV.3), she treats Eco’s fate as demonstration and proof of her case, leaving only one possible outcome for the nymphs under her protection.

4.6 This trajectory is clear in the end-of-episode choruses delivered by the Coro di Ninfe. In the first, “Poscia ch’in fiera guerra,” the story of Apollo and Daphne is treated just as an example from which they think Narciso should learn a lesson. In the second, “Quando primier chiedesti,” the nymphs admit that Narciso’s resistance to love means that all the joy and peace promised them by Amore have come to naught, leading them to exclaim—in a refrain for the first two (out of three) stanzas—that the god is but a deceitful liar (Ah, mentitor fallace, / queste le gioie son, quest’è la pace?). In the final stanza, they renounce him completely, arming their hearts with scorn. But despite Diana’s dire warning in II.4, the nymphs still seem open to persuasion: even after the unfolding of events in Episode III (including the Nunzio’s account of Narciso’s harsh rejection of Eco), the nymphs still think (“Io non credei già mai”) that the fault lies chiefly with Narciso, rather than Amore, for turning their woods to grief and lament. It is only Filli’s account in Episode IV of Eco’s transformation that turns the tables: the nymphs’ response to Diana’s second appearance in the opera (IV.3) is to admit that she was right all along. They submit to her protection (“Alma Dea che l’arco tendi”), turning the opening line of that Dafne chorus (“Nudo arcier che l’arco tendi”) to a different purpose.[70]

4.7 Immediately prior to that final chorus in Episode IV, Amore makes an appearance (following Diana’s), proclaiming his intention to punish Narciso. However, the nymphs pay him no attention (is he just speaking to the audience?). They also give him short shrift when they do acknowledge his second entrance, in Episode V, scene 2. Here they assume that the triumph he so proudly proclaims concerns Eco, and following an exchange speaking at cross-purposes, Amore leaves in an inconsequential huff. But after another Nunzio has explained what happened to Narciso (beginning with another cross-purpose misunderstanding), the nymphs acknowledge the moral prompted by the fates of Eco on the one hand, and Narciso on the other (ll. 1232–34 [S: 1203–5]).

Là dove regna Amor, regna tormento:

tra pudichi pensier, tra caste voglie

haverà gioia ’l cor, vero contento.[71](Where Cupid reigns, so does torment: / [only] amid pure thoughts and chaste desires / will the heart gain joy, true contentment.)

4.8 “Pure thoughts and chaste desires” may have been appropriate for any work intended for performance in a convent, if the original Narciso was. But it creates the “sad and tragic” ending noted by Monteverdi, and also, he might have added, a rather anodyne one: one could at least have expected some vigorous debate between Diana and Amore when they appear one after the other at the end of Episode IV. As for those final lines, however, something is missing in the sources. In V1, Rinuccini does what he did in Euridice and (probably) in the original version of Arianna: the action is divided into the Classical five parts, each of which should end with a chorus (typically, strophic) that in some way reacts to the previous action. Those choruses are generally cued by rubrics in V1, such as we can tell from the original folios that survive prior to the insertions producing V2.[72] But as was Rinuccini’s wont, he saved their writing for later.[73] Thus, the final choruses for Episodes I–IV form part of V2, in Rinuccini’s hand, although to be accurate, he could have added them at any time on whatever paper was available: they are treated as discrete units rather than as part of any running text (they begin at the top of a page, and the following episode starts on a new one), and they are not contingent upon the textual insertions in V2. Nor are they necessarily an integral part of the action. Indeed, one of them, “Quando primier chiedesti” (at the end of Episode II) either came from, or was developed into, a separate canzone within Rinuccini’s lyric output: it was published anonymously in 1618 in a Venetian poetic anthology of texts that had been, or could be, set to music, with the heading “Love’s Deceit. A Most Beautiful Musical Canzone, and New” (see Appendix 3).[74]

4.9 But Episode V lacks any such chorus (and any cue for it in V1), even though one would most likely have had to be present.[75] The only plausible suggestion—failing acceptance of procedural irregularity—is that Rinuccini was somehow keeping his options open in terms of how to bring Narciso to an appropriate conclusion for any intended audience. In one case, such a chorus could simply have reinforced the final lines of the text: that profane love can never bring “true contentment.” In another, however, the message could have been tweaked differently. Indeed, to follow what seems to have been done to the original ending of Arianna—with the addition of an apotheosis for Ariadne and Bacchus prompted by the appearance of Venus emerging from the sea and Jove in the heavens—one imagines that if needed, Rinuccini could have constructed something similar for Narciso, perhaps also inventing some reconciliation between Diana and Amore.

4.10 The separate fates of Eco and Narciso might appear unavoidable given the myth on which Rinuccini’s text was based. Ottavio Tronsarelli had a similar problem in his own Narciso, the first of a long series of theatrical works that the poet published as Drammi musicali (Rome: Francesco Corbelletti, 1632): here the final moral concerns the dangers of pride and the fragility of human life.[76] But Rinuccini had been perfectly willing to alter the end of the Orpheus story in Euridice, where Orfeo leads his bride from the Underworld without any test set by the gods that the standard version of the myth would have him fail. The poet did so, he said, because of the happy event for which that opera was commissioned: the marriage of Maria de’ Medici and Henri IV of France. He could easily have made some similar arrangement for Narciso to provide a conventional lieto fine, regardless of any fidelity to a prior story or fear of implausibility. That is certainly what Orazio Persiani did in his libretto for Narciso et Ecco immortalati, performed in Venice in the 1641–42 season (with music, now lost, by Filippo Vitali and perhaps Marco Marazzoli). Here both Narcissus and Echo regain their bodily forms and are united in happy marriage in heaven, thanks to the intervention of Apollo and with the approval of the other gods. If Rinuccini had done something of that kind, Monteverdi might have been happier with the result.

5. Designing a Libretto

5.1 It is a common mistake to read librettos either in purely literary terms or as mere fodder for musical setting. But they are theatrical texts in multiple senses of the word, one of which concerns, precisely, their place in the theater. A more careful examination of Rinuccini’s Euridice, for example, reveals just how much he cared about staging issues (who is where, when, and why), and Peri’s score (but not Caccini’s) shows how problems unforeseen in the writing process were identified and solved. The same is true of Striggio and Monteverdi’s Orfeo. In both works, too, we find what one might call implicit stage directions within the speeches assigned to individual characters or to the chorus. Any stage director needs to think in these exact terms, of course. Literary and music historians, however, can tend not to notice them.

5.2 In addition to the typical five-part division of the action, Narciso adheres to Classical precedent in other ways as well in terms of the unity of time and also of place (a single pastoral set).[77] Rinuccini is careful to have his characters note when events are happening, from early morning through midday (Narciso rejects Eco as they are resting by a stream to escape the heat) to late afternoon (Narciso hopes to hunt one more boar before the sun sets).[78] Rinuccini’s handling of the chorus of nymphs is also typical: it is a constant presence onstage from I.3 on (I.2 in V) and delivers the end-of-episode choruses as an ensemble, but individual members step out of the group for separate speeches (and are sometimes addressed by name in speaking with the principal characters).[79] The original terminology in V1 becomes confusing at this point, given that such speeches are often just labeled “Ch[oro],” although for staging purposes, their speakers would need to be identified differently, at least when two or more different ones were being used. F solved the problem by assigning speeches to a “Ninfa” and “Altra ninfa” in Episode II, scenes 1–2 and 3, and similarly for two members of the Coro di Cacciatori in V.1.[80] Of the five nymphs in II.3, one is Lidia by implication (she speaks of her lyre in l. 507 [S: 465], which she has played earlier), and another may be Amarilli. Two more nymphs have already been given names when addressed by other characters elsewhere within the text: Nisa in l. 232 and Licori in l. 375 (S: 190, 334). Add another, unnamed, nymph and this brings the total to the five needed for II.3, and a plausible enough number for the total Coro di Ninfe save for the extravagant references in the text to their great number (and likewise, of the hunters).

5.3 Lidia and Amarilli are betwixt and between: they belong to the Coro di Ninfe, but Lidia is also a named character who speaks in V1.[81] Amarilli is not (although she is mentioned), and her creation in V2 is part of a revision to Episode I, scene 2. The plan in V1 was to have the opening scene for Filli and Eco on their own—the model is the first scene of Torquato Tasso’s Aminta (1573)—and then for the Coro di Ninfe to enter in Scene 2, with two of them (so the subsequent text suggests) singing the song “Verginelle inamorate.” V2 revises this by allocating “Verginelle inamorate” to Lidia and Amarilli (and F makes that clearer still with the rubric “Lidia et Amarilli singing together”).[82] Nevertheless, V2 still has speeches for the Coro di Ninfe within that second scene, creating the problem that an additional Coro di Ninfe enters in I.3 (an inserted scene). Two separate choruses of nymphs is one too many, and F does the only logical thing to solve the problem; the speeches in I.2 are reassigned to create a scene for just four characters (Lidia, Amarilli, Filli, Eco) prior to the appearance of the other nymphs in I.3.

5.4 The source for F dealt with a number of such issues, though not all of them. Some of the insertions in V2 were intended to clarify the plot, such as when Filli is urged to keep secret the passion for Narciso that Eco has just confessed to her (ll. 168–69 [S: 132–33], an insertion at the end of I.1)—as Filli later (ll. 611–13 [S: 578–80]) admits she has done—or as Lidia and Eco argue over what Diana might teach them, in the extension to I.2 (in particular, ll. 202–9 [S: 160–67]). That argument becomes an important issue given Diana’s two appearances later in the opera, and what the chorus eventually agrees is the moral of the story. But other insertions created further problems. For example, the appearance of Elpino and the Coro di Cacciatori in the inserted scene at the beginning of Episode II makes scant sense given that it forces a different Coro di Cacciatori to appear alongside Narciso in Scene 2 (the original II.1). As was the case with the nymphs in Episode I, this is one chorus too many, but here, F does not present a viable solution given that the Coro di Cacciatori in Scene 1 sings a collective song, “Chi d’amor tra fiamm’ardente” (a nymph responds to it by noting the tanti cacciatori present). Despite the resulting inconvenience, however, this reveals the motive for at least some of the insertions in V2: to increase the musical possibilities of the text.

5.5 The basic assumption within any libretto by Rinuccini (and most others of this period and later) is that the action will take place in the declamatory musical style developed in the 1590s, chiefly by the Florentine composer Jacopo Peri, that we now call “recitative,” although the term is not entirely helpful. The end-of-episode choruses, however, will be more song-like, as one of the Coro di Ninfe suggests at the end of Episode I while they await Narciso (ll. 252–55 [S: 210–14]):

Ma deh, Lidia, fin tanto

ch’arrivi ’l bel pastore,

accorda l’aurea cetra al nostro canto,

perché più ratte se ne fuggan l’hore.[83](But ah! Lidia, until / the fair shepherd should arrive, / tune your golden lyre to our song, / so that the hours might pass more quickly.)

Lidia does precisely that to accompany the chorus ending the episode, which recounts the story of Apollo and Daphne (“Poscia ch’in fiera guerra”). F makes the point clearer still by preceding what the chorus calls “our song” with the instruction “Cantano” (“They sing”).

5.6 These two musical styles are cued by two types of poetry: versi sciolti in seven- and eleven-syllable lines for the declamatory passages, and a sequence of regular stanzas for the choruses.[84] In Narciso, the choruses at the end of Episodes I, II, and III are stanzaic canzones in seven-syllable lines (Episode I) or a mixture of sevens and elevens (Episodes II, III). However, the chorus at the end of Episode IV (“Alma Dea che l’arco tendi”)—based on one from Dafne—is in eight-syllable lines, also with a four-line refrain. One imagines that the refrain was intended for the full chorus and the individual stanzas for single members of it, on the model of similar “refrain” choruses in Euridice and Arianna.[85]

5.7 Such metrical distinctions make it relatively easy to determine how Rinuccini imagined his poetry being set to music, or at least, to predict its likely musical outcome, always allowing for surprises along the way.[86] In the case of any text for “recitative,” the composer would have to rely largely on its emotional content to determine greater or lesser degrees of expressive intensity, unless there were other structural or rhetorical cues prompting a particular musical response.[87] On the other hand, the position of “songs” within the action itself, on the relatively rare occasions when Rinuccini chose to include them, is established by the poetic meter. But the difficulty for him, and for many other theatrical poets, was that songs, as distinct from sung speech, threatened dramatic verisimilitude unless they could be introduced, precisely, as actual songs performed and recognized as such by the characters onstage.[88] Rinuccini can be nervous even in the case of end-of-episode choruses: hence the explicit invitation by the nymph for a musical performance at the end of Episode I. Despite the obvious paradox that the nymph is already singing (in recitative), sung speech is one thing, and song, another.

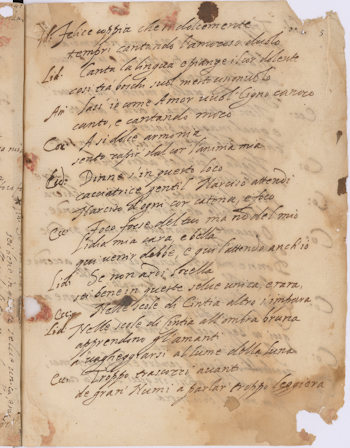

5.8 Songs at the beginnings of scenes need to be handled in a similar way. Eco and Filli’s discussion of their amorous entanglements in I.1 is interrupted by the sounds of offstage music. Eco calls Filli’s attention to them (ll. 164–65 [S: 128–29]: Ascolta, Filli, senti: / che suon, che canto è quello?), and Filli says that such “sweet accents” likely come from Lidia or Amarilli (ll. 166–67 [S: 130–31]: Taci: sì dolci accenti / sol da Lidia uscir puonno, o da Amarilli), or, so it turns out, both of them. This cues I.2, which begins with what V1 labels a “chorus,” singing about young maidens suffering unrequited love (“Verginelle innamorate”), with a text that itself refers to how the sounds of such songs, and of the lyre that accompanies them, are lost to the winds. This is a convenient way of getting new characters onstage: Rinuccini had used the same device to mark the entrance of the Coro di Soldati in Scene 2 of Arianna. But Filli’s subsequent comment makes it clear that this “chorus” is in fact a duet (ll. 188–89 [S: 146–47]: Felice coppia che sì dolcemente / tempri cantando l’amoroso duolo). Its performers also identify themselves: Lidia compares herself to a sad nightingale, while Amarilli says that she is a swan singing on the verge of death.[89]

5.9 Rinuccini often used such musical terms in his librettos (“suono,” “canto,” “accenti,” etc.) as a means of justifying, or excusing, the seemingly implausible musical medium in which the dramatic action is being carried out.[90] But songs also need to be distinguished in other ways. “Verginelle innamorate” consists of two equal stanzas (with a third one added in F) mixing eight- and four-syllable lines (the first rhymes a8a4b8c8c4b8). The pattern appears in Rinuccini’s other librettos as well; it derived from the anacreontic canzonettas that the poet Gabriello Chiabrera introduced into the solo-song repertory in the last decades of the sixteenth century. In Narciso, precisely the same structure is used for the entrance of the Coro di Cacciatori in the added II.1 (“Chi d’amor tra fiamm’ardente”; four stanzas), again to introduce new characters onstage while also, by virtue of its content, emphasizing the happy state of hunters who refuse love (a matter, they say, reserved for those who drink wine and lie on soft feather beds).[91] This is a revision in V2, and it appears to have encouraged Rinuccini to find within this part of the libretto still more opportunities for such singing.

5.10 For example, in V1 Narciso enters in II.1 and repeatedly rejects the nymphs’ amorous advances; he then heads off with Eco to pursue his greater love of hunting. In the revision to the end of this scene in V2 (now II.2), however, Narciso responds to the nymphs’ insistence that he should at least stay with them until dawn has broken by offering (in seven- and eleven-syllable lines, grouped in fours) to sing them a song (ll. 440–47 [S: 398–405]):

Benché desire ardente

m’inviti al bosco, al monte,

io vi vo’ far contente

finch’apparisca il sol su l’orizzonte,

leggiadre ninfe; e voglio,

se fede il canto impetra,

(porgimi la tua cetra)

tanti affanni quietar, tanto cordoglio.(Although ardent desire / may draw me to the forest and mountain, / I am willing to make you content / until the sun appears on the horizon, / fair nymphs. And I wish, / if song rings true, / (give me your lyre) / to calm such great torments and such grief.)

That parenthetical request for a lyre is made to Lidia, who had already “tuned” it for the chorus ending Episode I. But Narciso’s “song” that follows (“Se d’Amor nel regno crudo”), with seven four-line stanzas in eight-syllable lines, is, instead, a warning against placing any trust in Cupid, who is naked, blind, deaf to all musical entreaty, and so on, and who will therefore lead anyone astray. Narciso’s final stanza leaves no room for doubt (ll. 472–75 [S: 430–33]):

Di gioir non è speranza con Amor, datemi fede: rivolgete ratto il piede, fanciullette, a questa danza. (There is no hope for joy / with Cupid—trust me: / quickly withdraw your foot, / young maidens, from this dance.)

Rinuccini then has the typical problem of how to continue once the song is over and done. Returning to versi sciolti, one of the nymphs disputes the message of the song, and all Narciso can say is that those who wish to die may die, but a faithful servant of Diana (la selvaggia Diva) will live happily. He then exits as he did in V1 (prior to the insertion of the song), making his own plea to Diana that she should guide his arrows straight to their bestial targets.

5.11 Narciso’s reference in the final line of his song to questa danza is to the “dance” in which Cupid leads the unwary. But the strong stresses of those eight-syllable lines are also amenable to dance in the more literal sense: “Se d’Amor nel regno crudo” is, in effect, a dance-song. One can easily imagine how Monteverdi might have set it, on the model of the similar dance-songs in his Orfeo, such as “Vi ricorda, o boschi ombrosi” (Act II) in the same poetic meter: with a tuneful melody, driving rhythms, and instrumental ritornellos allowing for some kind of stage choreography. But as Monteverdi delved further into Narciso, he would have found precious few opportunities for other such musical moments: there are far more in Orfeo. He complained about the casting problems of Narciso with its too many sopranos (as nymphs) and tenors (shepherds) creating a lack of variety. That term, as with varietas, is open to interpretation in terms of a variety of voices, of events, of emotional situations, of rhetorical styles, or of poetic structures.[92] But Monteverdi probably would also have wanted more “songs” than Rinuccini’s libretto allows.

6. Three Messengers

6.1 In fact, Narciso has more songs than the first libretto by Rinuccini that was set by Monteverdi, his Arianna (1608).[93] In that case, the composer may have cared less about the issue because he was writing to a specific commission (for the wedding of Prince Francesco Gonzaga and Margherita of Savoy), or perhaps he expected nothing more given that Arianna was labeled explicitly by Rinuccini as a tragedia per musica. Narciso, however, is more in the manner of a favola boschereccia. Rinuccini writes in typical pastoral mode, also drawing heavily on Tasso’s Aminta on the one hand (which includes a character named Elpino), and Battista Guarini’s Il pastor fido on the other (with an Amarilli); Guarini’s play was probably also one source for Rinuccini’s inevitable echo-scene in IV.2.[94] However, Narciso also reflects a number of problems of genre, even apart from the lack of a conventional lieto fine.