The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 29 (2023) No. 1

The “Memento Mori Sibylla” of Johann Jacob Froberger

Yves Ruggeri*

Abstract

Among the keyboard pieces in a recently discovered autograph collection by Johann Jacob Froberger (the Montbéliard Manuscript, now in private hands) is a méditation composed ca. 1666 and inscribed “Memento Mori Sibylla.” A complete transcription is given here. The work exemplifies the style of pieces to be played “avec discrétion,” according to the composer’s instructions. Froberger presumably intended to dedicate the manuscript to his patroness and pupil Princess Sibylla of Württemberg, in whose household he lived in the last years of his life.

2. Historical and Biographical Background

3. The Montbéliard Manuscript and Its Provenance

4. The Title and the Composition

1. Introduction

1.1 In 2006 a previously unknown Johann Jacob Froberger autograph was auctioned by Sotheby’s of London.[1] The manuscript is of extraordinary interest. It includes fifteen previously unknown keyboard works as well as a number of pieces known from other sources but appearing here in significantly different versions. Moreover, the manuscript dates from Froberger’s last years and thus offers a window into his late compositional style. Internal evidence shows that copying took place around 1666–67; the composer died in 1667. Captions indicate that several of the pieces were composed in Montbéliard (then a principality in the Holy Roman Empire, now a town and its environs in France). It is therefore appropriate to refer to this source as the Montbéliard Manuscript.[2]

1.2 Once the manuscript was sold at auction, it became inaccessible to scholars. But in 2016, at a conference in Royaumont, participants were allowed to hear, and hear about, some of the music.[3] Moreover, the owner of the manuscript (who wishes to remain anonymous) had previously given permission for a transcription of the “Memento Mori Sibylla,” an extraordinary masterpiece, otherwise unknown, which we publish here for the first time (Appendix).[4] This is one of several monumental pieces in the last part of the manuscript—two méditations and two tombeaux—that significantly enrich Froberger’s legacy, and more broadly the corpus of harpsichord music of the seventeenth century.

2. Historical and Biographical Background

2.1 The appearance of Johann Jacob Froberger (1616–67) in Montbéliard is directly related to the presence there of Princess Sibylla of Württemberg (1620–1707). They must have known each other as children at the ducal court of Württemberg in Stuttgart: she was the daughter of Duke Johann Friedrich; he was the youngest son of Basilius Froberger, a singer in the Württemberg court chapel who became Kapellmeister in 1621. Around 1634 the young Johann Jacob left for Vienna, where by 1637 he was appointed organist in the imperial Hofkapelle. As for Princess Sibylla, she moved to Montbéliard (Mömpelgard in German) on November 22, 1647, at the age of twenty-seven, to marry her cousin Prince Leopold-Friederich of Württemberg-Mömpelgard (1624–62), who had succeeded his father as duke of Württemberg-Mömpelgard in 1631. Sibylla resided with her husband in the Montbéliard Castle from 1647 to 1662.

2.2 On Sunday, June 15, 1662, Duke Leopold-Friederich suddenly fainted while attending Mass.[5] Immediately brought to his apartments, he died two hours later. As Leopold-Friederich and Sibylla had no children, his half-brother Prince Georg of Württemberg-Mömpelgard (1626–99) became Georg II, the new duke of Württemberg-Mömpelgard. Sibylla remained in the Montbéliard Castle for another year after her husband’s death. According to the marriage contract, Sibylla’s dowry was secured by the seigneuries of Horbourg and Riquewihr, and to a lesser extent that of Héricourt. As the seigneuries of Horbourg and Riquewihr could not devolve to her before the passing of the dukes’ mother, Duchess Anna Eleanor, it was Héricourt Castle that was finally granted as Sibylla’s new residence. On August 11, 1662, Georg II ordered its restoration, and on July 31, 1663, Princess Sibylla moved there, just a few kilometers from the Montbéliard Castle.

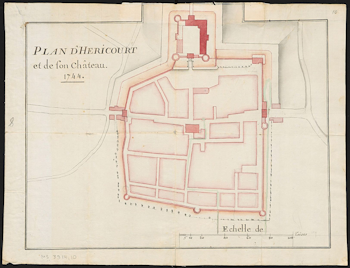

2.3 The newly restored Héricourt Castle (Fig. 1) was flanked by four large towers, surrounded by walls of great strength, and defended by a moat that could be filled with water. The main building had several floors and contained spacious rooms. One of these rooms had a domed ceiling, decorated with portraits of the princes of Württemberg-Mömpelgard. At Sibylla’s request, a small building was added to the castle to serve as a chapel where the chaplain celebrated services in German.[6]

2.4 The castle allowed Sibylla to have a peaceful life in a pleasant place. At Héricourt, Sibylla was particularly devoted to reading and music. Charles Duvernoy, pastor of Héricourt at that time, related as much in a dedicatory letter to Duke Eberhard III of Württemberg, the princess’s brother: “If you could see her way of life, you would see … in her study a number of very rare books, which, along with … diverse pieces of instrumental music, are the source of most of her worthy conversations; you would see a sister who loves God, loves you, and by her prudent conduct honors the House she descends from.”[7] Sibylla remained in Héricourt until the French occupation of Franche-Comté in the Franco-Dutch War. In 1676 Louis XIV ordered the fortifications dismantled;[8] in 1677 the princess and the members of her court left Héricourt, retiring to Württemberg. She died in Stuttgart on May 21, 1707, at the age of eighty-seven.

2.5 As for Froberger, from 1637 to 1658 he alternated between periods of employment at the imperial court in Vienna and periods of extended travel and music-making throughout Europe. In 1658 his appointment in the imperial court chapel came to an end. We do not know the full extent of his travels thereafter (though Paris was evidently a principal destination), but he was certainly in Montbéliard on September 20, 1664, for Duke Georg II noted in his diary that on that date “Mr. Froberger had an audience.” [9] As mentioned above, the composer copied music into the Montbéliard Manuscript around 1666–67. He had evidently come to Héricourt to join the princess he had known as a child in Stuttgart. There is no further record of Froberger in Montbéliard until his death in the castle of Héricourt on Tuesday, May 7, 1667. He was buried on Friday, May 10, in the Catholic land as he had wished, in the church of Bavilliers, north of Héricourt.[10] Duke Georg II noted in his diary that Sibylla was very much affected by the death of the musician: “10 [May 1667] … Froberger has been buried by order of the Princess of Héricourt. [marginal note:] The Princess of Héricourt came to Montbéliard on May 15. [She] greatly regrets the sudden death of the musician Froberger and had him buried with solemnity.”[11]

2.6 A letter Sibylla wrote to Constantijn Huygens on Tuesday, June 25, 1667, is the source of the date of Froberger’s death: he “died seven weeks ago today at five o’clock during his vespers prayers”—thus, on Tuesday, May 7.[12] The letter also mentions that on the preceding day, May 6, Froberger arranged for his own burial—a date confirmed by Jean-Nicolas Binninger.[13] These dates are those of the Julian calendar, still in force in Montbéliard in 1667. According to the Gregorian calendar, already in use in most of Europe at that time, Froberger gave his last wishes on May 16, died on May 17, and was buried on May 20.

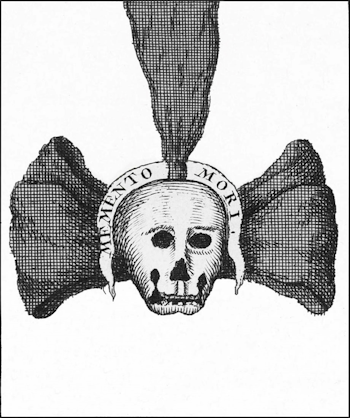

2.7 Of particular interest here, the letters between the princess and Huygens emphasize her love for music and her musical talent, and they reveal the artistic relationship between the musician and his patroness. “I also am a lover of noble music,” she writes,[14] and she characterizes herself as “a modest pupil left alone by my dear, honorable, faithful, and diligent teacher.”[15] She was apparently a very talented harpsichordist who perfectly mastered Froberger’s style. Huygens mentions that Froberger “often declared to me that one who could not see Your Highness playing his pieces could not tell whether it was she or he himself who was playing them.”[16] Her interest in music is confirmed by the engraving on her sarcophagus, probably created according to her own specifications, where she appears surrounded by various musical instruments, including a small organ and another keyboard instrument, probably a spinet (Fig. 2).[17]

2.8 In the letter just cited, Huygens declares Sibylla of Württemberg the “heiress of all the mastery of the deceased.” She was undoubtedly the true heir to the music of Froberger and had perfectly understood that musician’s exceptional worth. In reading her writings, we feel her mourning his death: “… what art and what great skills have died with him.”[18] Froberger offers a wonderful example of this art in the “Memento Mori Sibylla”!

2.9 In the manuscript, Froberger does not specify the date of composition of the “Memento Mori Sibylla.” However, he does name Madrid as the place of composition,[19] and this provides an important clue. Although we have no other evidence of a trip to Madrid by Froberger, we know that the wedding of Margarita Teresa of Austria, Infanta of Spain, to Emperor Leopold I of Austria, was celebrated by proxy on Easter Sunday, April 25, 1666, at the court of Madrid. Froberger might have been in Madrid on this occasion,[20] perhaps even as a diplomatic representative for Sibylla. From this we may hypothesize April 1666 as the date of composition of the “Memento Mori Sibylla.”

3. The Montbéliard Manuscript and Its Provenance

3.1 The manuscript has a beautiful red leather binding with decorations in gold repoussé that seem to establish a clear link to the imperial court of Vienna.[21] Both the front and back covers display in their center panels an imperial eagle with two heads, armed with two swords, which was the heraldic symbol of the Holy Roman Empire. In fact, the imperial symbol on the binding of the Montbéliard Manuscript was made with the same stamp that was used on the bindings of at least three other manuscripts, all now in the Austrian national library in Vienna: a collection of pieces by Johann Heinrich Schmelzer, a colleague of Froberger’s who served as a violinist for Emperor Ferdinand III and then as Vice-Kapellmeister for Emperor Leopold I;[22] a catalog of musical works in the collection of Leopold I (where the binding also displays the small lilies found on the binding of the Montbéliard Manuscript);[23] and a collection of suites copied for Leopold I.[24] Fig. 3 shows the identical coat of arms on the bindings of the Montbéliard Manuscript and the collection of suites.

3.2 Yet unlike those other manuscripts, the Montbéliard Manuscript was never in the imperial library. Moreover, it contains a curious title page in an unidentified hand: “Livre Primiere. Des Fantasies, Caprices, Allemandes, Chigues, Couranttes, Sarebandes, Meditations. Composées. par Jean Jacque Froberger. Organist. de la chambre de Sa Majeste Imperiale.” The page is in French, not Italian as we would expect if the manuscript were intended for the emperor, and it inexplicably identifies the volume as “Book One,” as though this were the first in a planned series.[25]

3.3 There is evidence in Froberger’s correspondence with Huygens that he had intended to return to Vienna around autumn of 1666,[26] and the contents of the Montbéliard Manuscript seem to support the idea that this volume was initially meant as a gift for Leopold I. Part 1 (six fantasies) and Part 2 (six caprices) recall the organization by genre of Froberger’s earlier manuscripts for the emperor, and Part 3 begins with the “Allemande, faicte sur le Couronnement de sa Majesté Impériale à Franckfurt” (from Suite XV, FbWV 615), marking Leopold’s coronation in Frankfurt, on August 1, 1658. But the suites and other items that occupy the rest of the manuscript include several important pieces that refer either to Sibylla of Württemberg and the principality of Montbéliard, or to Froberger himself in the Méditation on his future death:

“Allemande, faict à Montbeliard, a l’honneur de Son Altesse Serenisme Madame Sibÿlle, Duchesse de Wirtemberg, Princesse de Montbeliard” (Suite XVIII, FbWV 618)

“Afligée, la quelle se joue lentement avec discretion, faict à Montbeliard pour Son Altesse Serenissime Madame Sibÿlle, Duchesse de Wirtemberg, Princesse de Montbeliard”[27] (FbWV 657)

“Meditation, la quelle se joue lentement avec discretion, faict sur ma Mort future” (Suite XX, FbWV 620)

“Meditation, la quelle se joue lentement avec discretion. faict à Madrid, sur la Mort future de Son Altesse Serenisme Madame Sibÿlle, Duchesse de Wirtemberg, Princesse de Montbeliard” (FbWV 658)

“Tombeau, le quel se joue lentement avec discretion, faict sur la tres douloreuse Mort de Son Altesse Serenisme Monseigr le Duc Leopold Friderich de Wirtemberg, Prince de Montbeliard” (FbWV 659)

The very personal nature of these titles is inconsistent with a manuscript designed to be part of Leopold I’s collection. Perhaps Froberger initially began compiling the manuscript with the emperor in mind and then switched his focus to Sibylla. Yet the manuscript includes no dedication, to Sibylla or anyone else. It is a fair copy in oblong octavo format—thus probably prepared with binding in mind. The absence of a dedication suggests that Froberger never completed the book, and that binding took place after his death.

3.4 It seems clear in any case that Froberger’s eventual intention was to dedicate the manuscript to Sibylla. It is plausible that the princess discovered the manuscript only after Froberger’s death. As a matter of fact, she mentioned to Huygens that after the musician’s death, she found new pieces difficult to interpret without the advice and the prodigious imagination of her master.[28] This comment seems particularly apt for the “Memento Mori Sibylla” and the Tombeau for Leopold-Friederich of Montbéliard.[29]

3.5 If this hypothesis is correct, then it could have been Sibylla herself who ordered the imperial binding and the title page, to honor Froberger and his title of “Organiste de la chambre de sa Majesté Impériale” (Chamber Organist to his Imperial Majesty). That is the very title by which she identified him in her letter to Huygens of June 25, 1667: “Keyserlichen Mayestäts Kamer Organist.” In view of the promise she had made to Froberger never to share his works with other people,[30] and because the manuscript contains so many personal references, it is likely that Sibylla never disclosed the existence of the Montbéliard Manuscript to anyone.[31]

4. The Title and the Composition

4.1 In the Montbéliard Manuscript, the two méditations written for Froberger and Sibylla respectively are clearly intended to echo each other, as can be seen from their titles:

“Meditation, la quelle se joüe lentement avec discretion, faict sur ma Mort future” (Méditation, which is to be played slowly with discretion, made on my future death), and after the music: “NB Memento Mori Froberger?”[32]

“Meditation, laquelle se joüe lentement avec discretion. faict à Madrid sur la Mort future de Son Altesse Serenisme Madame Sibӱlle, Duchesse de Wirtemberg, Princesse de Montbeliard” (Méditation, which is to be played slowly with discretion, made in Madrid on the future death of Her Most Serene Highness Madame Sibylla, Duchess of Württemberg, Princess of Montbéliard), and after the music:“NB Memento Mori Sibylla?”

In both pieces, the “nota bene” inscription ends with a question mark; its significance will be considered below. The “Memento Mori Froberger” is only 20 measures long, while the “Memento Mori Sibylla” contains 49 measures (26 in the first part and 23 in the second part).[33] The former substitutes for the allemande in a suite of dances, whereas the latter is a stand-alone piece.

4.2 In the seventeenth century, the brevity and fragility of life, the vanity of pleasures and worldly goods, and the need for morality in life in view of the certainty of death, were frequent themes in spiritual poetry and in art. In painting, a “memento mori” was a symbol that served as a reminder of our mortality, such as a human skull symbolizing death, flowers symbolizing the brevity of life, an hourglass or burning candle for the passage of time, or a crown of laurels for the immortality of the soul. An allegorical still-life painting featuring such symbols was called a “vanitas” (a reference to the biblical verse “Vanity of vanities …,” Ecclesiastes 1:2). Thus, the “Memento Mori Froberger” and “Memento Mori Sibylla” were musical representations of the prospect of future death.

4.3 An interesting side note: in Württemberg “Memento Mori” also served as the motto of an order of knighthood, the Order of the Skull,[34] founded in 1652 by Sibylla’s cousin Silvius Nimrod (1622–64), Duke of Württemberg-Oels, who was also its first Grand Master. The device of this order is a skull nested in a black-ribbon bow and wearing a white ribbon that bears the motto “Memento Mori” (Fig. 4). Silvius Nimrod had been granted the Duchy of Oels by Emperor Ferdinand III on December 15, 1648. It is unknown whether he had any direct or indirect influence on Froberger.

4.4 Musical “méditations” should be understood in the context of prayer. In the mid-seventeenth century, to pray and to meditate became nearly synonymous, and authors of devotional literature often emphasized the fleeting nature of time and the imminence of death.[35] Jean de Saint-Samson provides very good examples in his Méditations pour les retraittes ou exercises de dix jours,[36] in particular his Méditation 13, on death:

Exercise 1: “Tout est mort, tout meurt tout mourra, on ne sçait quand …” (Everything is dead, everything dies or will die, we don’t know when …)

Exercise 4: “Pensons à la Mort une ou deux fois châque jour, l’envisageans comme le poinct de nostre entrée à la vie eternelle.… Nous ne sçavons quand elle arrivera: Ce sera peut-estre demain, & encore plûtost …” (Let us think about death one or two times each day, envisioning it as the point of our entry to eternal life.… We do not know when it will arrive: it could be tomorrow, and even earlier …)

4.5 In his commemorative remarks cited above, Jean-Nicolas Binninger indicated that Froberger himself “regularly repeated this exhortation: watch and pray, for you do not know when your time will come.”[37] Here Froberger echoed recommendations found in the Gospels.[38] Thus, it was through prayer and meditation that he prepared himself for the idea of death. We find this sequence in the music itself, where the Méditation for Sibylla (for instance) concludes with a note in the form of a question: “Memento Mori Sibylla?” The question mark after the imperative future of “meminisse” (“memento”) and the infinitive “mori” seems to act as a reminder not only concluding but also reinforcing the Méditation: Sibylla, will you remember that you must die? This rhetorical question calls for an obvious answer, further strengthening the spiritual purpose and the religious truth of the Méditation.[39]

4.6 The Méditations for Sibylla and Froberger do not differ fundamentally in spirit from pieces that the composer entitled Lamentation, Tombeau, Plainte, or Afligée—all titles inviting emotional introspection. As the examples in par. 3.3 above illustrate, such pieces have programmatic titles that refer to particular individuals or events, and the performer is directed to play them slowly (lentement) and “with discretion” (avec discrétion). But just what is it that is left to the “discretion” of the performer?[40] Sébastien de Brossard’s definition of the Italian term “discreto” (or “con discrezione”) simply emphasizes calm moderation,[41] and Johann Mattheson, though he referred explicitly to Froberger, interpreted the term only as a reference to tempo variation in toccatas and fantasies.[42] Yet one of the surviving copies of a relevant piece by Froberger, his Tombeau in memory of the lutenist Blancrocher, who died in Paris in 1652, offers a useful clue: the instruction “sans observer aucune mesure” (without observing any measure—i.e., without beating time) follows the words “à la discretion.”[43] Surely the instruction should not be taken literally, as a call for entirely improvisatory rhythm; Froberger’s highly detailed rhythmic notation here and in other such pieces suggests otherwise. In the Méditation for Sibylla (see the score in the Appendix), we might note especially the carefully notated, complex rhythmic figures in mm. 1, 12, 15, 24, 31, 38, and 43.

4.7 David Schulenberg—pointing out that Froberger’s complex melodic figures are embellishments, decorating simple underlying progressions—offers this helpful clarification:

In older music, including the vocal polyphony of the Renaissance, the beats come relatively quickly and the notes move regularly.… In the new type of music played with “discretion,” however, the beats could move more slowly and less consistently. Time stands still, in a sense, within or between the slow-moving beats of a lament by Froberger or a prelude by [Louis] Couperin. Present-day musicians typically subdivide such long beats … in an effort to place every small note value at its arithmetically correct time point within the measure. This cannot be what Froberger had in mind, however, and his calls for discretion must have been intended to make that explicit.[44]

This seemingly paradoxical combination of precise figuration, carefully notated, with more freely moving beats helps explain Sibylla’s assertion that “whoever has not learned the pieces from the late Froberger himself, could not possibly play them with the right discrétion, as he himself played them.”[45]

4.8 In sum, the terms “méditation,” “lentement,” and “avec discrétion” describe, respectively, the serene atmosphere, slow tempo, and metrical flexibility of the Méditation for Sibylla, as it engages in devotional introspection and the contemplation of death. This late style of Froberger’s apparently resulted from his contact with French musicians during his first stay in Paris, around 1652. The Tombeau for Blancrocher might well be the composer’s earliest piece calling for performance avec discrétion—a new style that would ultimately become his signature.

5. Notation and Performance

5.1 Froberger marked only a few slurs in the Méditation for Sibylla, but they are informative. Seven of them (found mostly at the beginning of the piece) indicate ports de voix (Ex. 1).[46] Presumably Froberger meant to write a slur in m. 29, where the passage prefigures that in m. 36. Elsewhere (Ex. 2) slurs seem to indicate a shift in fingering or hand position;[47] the shift in m. 34 (Ex. 2b) naturally involves a slight interruption of the sound. Indeed, as Howard Schott has proposed, where Froberger shows a dotted rhythm at the beginning of a group of sixteenth notes (Ex. 2b; Ex. 3), he probably meant to indicate an agogic accent—that is, a slight delay before the second note of the figure.[48]

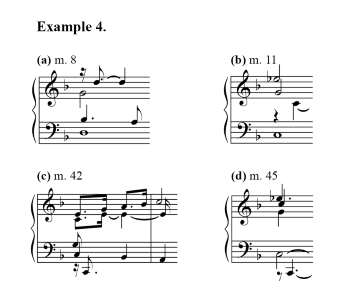

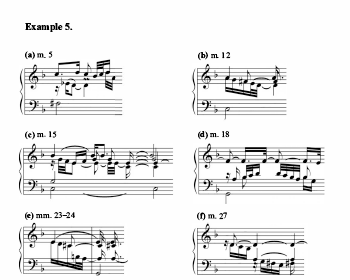

5.2 A rest before an individual note in a chord probably indicates a simple arpeggio (Ex. 4). Elsewhere, however, Froberger provides a wide variety of written-out arpeggios in style brisé, some simple and others more elaborate (Ex. 5). Some of these detailed, written-out arpeggios are unique to the “Memento Mori Sibylla”; nothing like them can be found in Froberger’s other works, including those in the Montbéliard Manuscript.

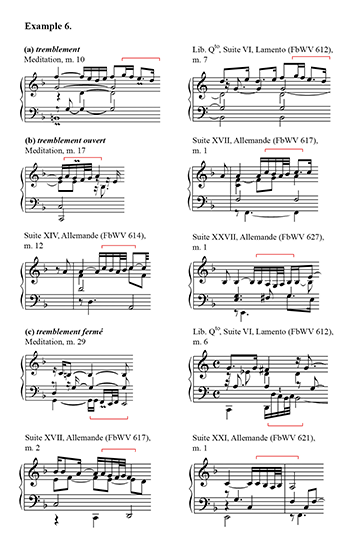

5.3 The composition includes twenty-one explicit ornament signs: nineteen tremblements and two pincés. The tremblements (trills), influenced by the French style, normally begin on the auxiliary note. As can be seen in the illustrations in Ex. 6, these tremblements can serve as models, showing us how to ornament similar figures in other works by Froberger. Note that in one case, the Lamento from Suite XII shown in Ex. 6c—which is found in the autograph “Libro quarto”—Froberger has given the same ornament in a similar context, marking it there with a t.

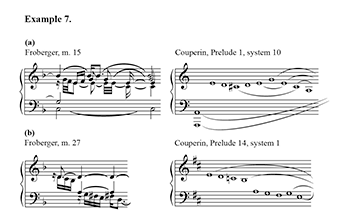

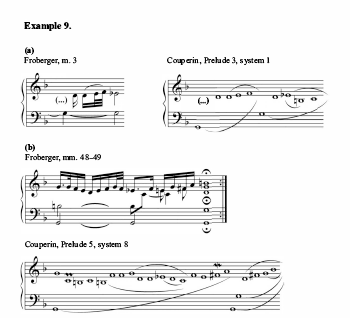

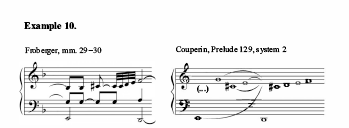

5.4 The Méditation for Sibylla presents passages that are very similar to some of those found in the “préludes non mesurés” commonly attributed to Louis Couperin. (Glen Wilson has argued that the “Mr. Couperin” who wrote these and other pieces was actually Louis’s younger brother Charles, 1638–79.[49]) Whether the similarities are evidence of influence of one by the other or simply a matter of common formulas used by both composers, Froberger’s detailed and precise notation helps us to interpret the unmeasured notation in Couperin’s preludes, and conversely, Couperin’s arpeggios can suggest a manner of performing analogous passages by Froberger. Ex. 7 shows the identical use of ties to indicate arpeggios.[50] In Ex. 8a the musical phrases are virtually identical (even including the trill on g′), so Froberger’s rhythmic notation helps us imagine Couperin’s rhythm. In Ex. 8b Couperin’s more elaborate arpeggios could be borrowed for Froberger. The passages in Ex. 9 use the very same harmonic pattern, alternating major and minor thirds or sixths. Finally, Ex. 10 suggests an appealing way to interpret the Couperin, using thirty-second notes.

5.5 Bob van Asperen emphasizes how deeply Couperin’s unmeasured preludes were indebted to the style of Froberger[51] and suggests that the unmeasured preludes were written after Froberger’s first visit to Paris, which probably occurred late in 1652. He goes on to argue that the references to Couperin’s style in Froberger’s own late works (and here we include the Méditation for Sibylla, probably written, as we have seen, in 1666) might indicate that Froberger intended to memorialize the late Couperin.[52] (Louis had died in 1661.) In any case, it seems likely that Froberger became particularly sensitive to the style of Couperin’s preludes during his second visit to Paris, in 1660.

6. Musical-Rhetorical Figures

6.1 As readers of this Journal know, seventeenth-century theorists’ application of the principles of classical rhetoric to musical composition is a complex and multi-faceted topic. Froberger’s likely understanding of this subject derived mainly from his youthful studies in Rome with Girolamo Frescobaldi and Athanasius Kircher,[53] though he probably encountered discussions of rhetoric in his later travels as well. In any case, as we study the “Memento mori Sibylla,” with its astonishing array of rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic gestures, it is the musical-rhetorical figures cataloged by Kircher and others that seem particularly compelling.[54] Kircher wrote that just as an orator “moves the listener through an artful arrangement of tropes, from laughter to tears, then suddenly to pity, now and then to indignation and anger, sometimes to love, piety and righteousness, or to other opposing feelings, so too does music [move the listener] through the artful combination of musical phrases and gestures.”[55] René Descartes, in a passage on the pleasure we derive from various musical figures (which are “related to those of rhetoric used in speech”), compared counterpoint and other artifice in music to acrostics and similar mind games in poetry, “which, like our music, was invented to entertain our minds and arouse various passions in our souls.”[56]

6.2 Kircher classifies the emotional states, or “affections,” aroused by music into three main categories: joy, serenity, and sorrow. He states that in comparison with joy, serenity enjoys a slower tempo; it “generates feelings of piety, love of God, … and contempt for worldly affairs, and finally it moves us to love heavenly things.”[57] In other words, the Méditation for Sibylla reflects a pious submission to death, with the slow tempo contributing to the serene mood.

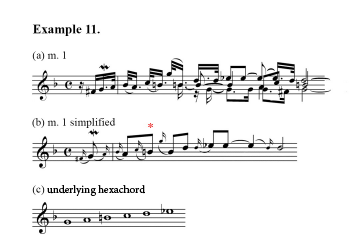

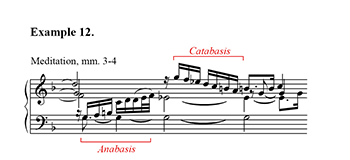

6.3 Yet the story the Méditation tells is one of difficult and only gradual acceptance. While the first four measures occur over a simple G pedal point in the bass, sounding the knell of future death, the initial declamatory phrase is complex. It comprises a succession of melodic intervals accentuated by Lombard rhythms, making tormented harmony, including successive ports de voix hiding a G major chord (see Ex. 11). The b′‑natural marked by an asterisk in Ex. 11b might be heard as an anticipation of the G‑major harmony not yet firmly stated.[58] (The first G‑minor chord comes only in m. 5.) Underlying that complex melodic material is a hexachord with a major third and a minor sixth: G–A–B♮–C–D–E♭ (Ex. 11c). D’Alembert would later describe a constellation of consonances encompassing these very pitch relationships.[59] The hexachord recurs in mm. 3–4, still over the G pedal point, but now the ascending g–e′‑flat scalar pattern is answered by a descending pattern, covering the minor sixth from g″ to b′‑natural (Ex. 12). Kircher describes the anabasis, or ascending scale figure, as an expression of exaltation or eminent thoughts,[60] and the catabasis, or descending scale figure, as an expression of dispirited or lowly thoughts.[61] In sum, the opening four measures, held together by the tonic pedal intoned in the bass, are deliberate rather than exuberant; they prepare the soul for meditation with melodic complexity and contradictory, ultimately negative, emotions.[62]

6.4 Finally, at the beginning of m. 5, the bass begins to move, first to a neighboring f‑sharp and then to the phrase shown in Ex. 13, which borrows from Froberger’s own Toccata VI “da sonarsi alla Levatione” (FbWV 106), found in the autograph “Libro Secondo.” Van Asperen characterizes this phrase as a “mystic chromatic progression”;[63] certainly the allusion to the Elevation of the Host reinforces the spiritual and meditative character of the piece. The same harmonic progression may also be found in Toccata XV (FbWV 115); see Ex. 13c.

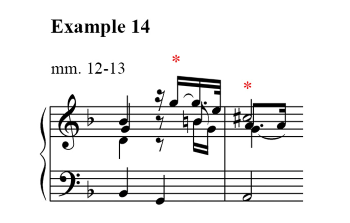

6.5 The piece continues in much the same vein as it started: it plays with contrasts, chromatic intervals, complex musical figures, and unexpected dissonances, all aimed at moving the soul. At the same time, it avoids expressive elements incompatible with meditation; for instance, the soprano stays away from augmented fourths, which would be considered a symbol of lamentation. (There is, however, one prominent arpeggiation outlining a diminished fifth; see Ex. 14.) Moreover, the piece does all this in a remarkably unidirectional manner, the first half making a long, slow melodic descent from g″ (m. 1) to d′ (m. 26). In preparation for the cadence in D that ends the first half, there is another anabasis–catabasis pair (mm. 22–24), once again arriving on the negative side of contradictory emotions.

6.6 In contrast with the tormented beginning of the first half, the second half immediately introduces serenity, with a magnificent descending-and-ascending arpeggio in sixteenth notes, an arpège coulé starting from d′, going down to d, and back to d′ (Ex. 15).[64] Now the anabasis–catabasis pairing is reversed: the anabasis echoes the catabasis, concluding the paired gesture with positive feelings. Such catabasis–anabasis pairing recurs several times in the closing measures of the piece, in mm. 40–41, 45–46, and 48. Furthermore, the second half is remarkably unidirectional: it makes a long, slow, overall ascent from d′ (m. 27) to g″ (m. 45), in mirror-image symmetry with the first half.

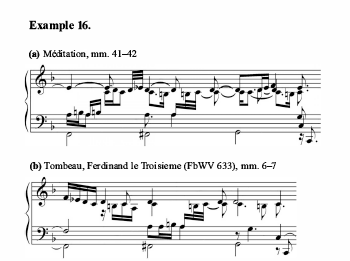

6.7 Thus, the two parts of the “Memento Mori Sibylla” express opposing affections, a phenomenon called antitheton or antithesis by Kircher.[65] The first part (mm. 1–26) may be understood in terms of humility and oppression, led mostly by feelings of apprehension and despair, and the second part (mm. 27–49) in terms of elevation and dignity, led by feelings of faith and hope. Throughout, of course, the focus is on the proximity of death. It is unlikely to be a coincidence that the ascending chromatic motion of the bass line and the figuration preparing the dominant chord in mm. 41–42 of the Méditation for Sibylla closely resembles those of mm. 6–7 in the “Tombeau faict sur la tres douloureuse mort de sa Majesté Imperiale le Troisiesme Ferdinand” (FbWV 633), as shown in Ex. 16.[66]

6.8 Near the beginning of the second half, Froberger states a melodic flourish twice at different pitch levels (with a modest adjustment of the surface rhythm: see the red brackets in Ex. 17a) and its introductory gesture a third time (see the blue brackets). A few measures later (Ex. 17b) he restates that entire passage a fourth higher.[67] Kircher refers to musical repetition as anaphora, a way to strengthen and intensify a musical idea.[68] While transposing a passage up a fourth is not precisely what Kircher has in mind for climax or gradatio—a series of stepwise rising sequences—we might nonetheless infer a desire for the heavenly kingdom, as that figure implies.[69]

6.9 As the piece approaches its final cadence, rhetorical figures spill over each other (Ex. 18): the passus duriusculus (chromatic motion) to introduce the C minor chord, from b‑flat to b′‑natural and then e″‑natural to e″‑flat;[70] the ensuing gesture, introducing the highest note in the passage, g″, and then immediately leaping back to e″‑flat, which might be heard as a musical exclamation (exclamatio), rather like the words “O Lord!” in a prayer;[71] a catabasis–anabasis pair that, in its descent to d′, recalls the overall descent of the first half, the bass responding with a rapid rise from G to g; and finally, a sudden and unexpected break, a giant leap from g to C in preparation for the D–G cadence that will end the piece. That last gesture, the huge leap, might have been described by Kircher as an Abruptio, “an unexpected rupture in a musical passage,” though the decorative cadence that follows might not be the “rapidly completed thought” he had in mind.[72]

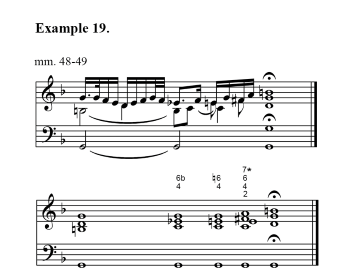

6.10 The Méditation having arrived at its home key of G, the concluding decoration (Ex. 19) moves from a catabasis–anabasis pair around g′ to an unexpected and dark e′‑flat (a last reminder of the opening of the piece), and finally makes an ascending harmonic progression that allows the B‑natural of the Picardy third to move from the middle voice to the top voice, in a shining G major chord. This harmonic progression is described by Brossard as a major seventh on a tenue.[73] Brossard refers to it as “a master stroke that we should admire rather than imitate.”[74] This conclusion represents the last move from darkness to light—perhaps the divine light? Memento Mori Sibylla?

Acknowledgments

I would like to sincerely thank the owner of the Montbéliard Manuscript for giving me access to this precious document, which allowed me to study it with great interest and emotion. The musical community will also appreciate the exceptional permission he granted for the publication here of the full musical text of the “Memento Mori Sibylla.” I would like to thank Laurent Guillo for the information kindly provided about book bindings and his important help. Finally, I would also like to thank Lois Rosow, Alexander Silbiger, Denis Herlin, and Mary Yeung for their kind support and trust in me for the publication of this article.

Appendix

Transcription of Froberger’s Méditation “on the future death” of Sibylla of Württemberg

Examples

Ex.1. Froberger, Méditation: slurs indicating ports de voix

Ex. 2. Froberger, Méditation: slurs indicating shifts in fingering or hand position

Ex. 3. Froberger, Méditation: dotted figures suggesting agogic accents

Ex. 4. Froberger, Méditation: rests indicating simple arpeggios

Ex. 5. Froberger, Méditation: written-out arpeggios

Ex. 6. Froberger, Méditation: tremblements that can serve as models, with parallel passages from Froberger’s suites

Ex. 7. Froberger, Méditation, and Louis Couperin, unmeasured preludes: the use of ties to indicate arpeggios

Ex. 8. Froberger, Méditation, and Louis Couperin, unmeasured preludes: melodic similarities

Ex. 9. Froberger, Méditation, and Louis Couperin, unmeasured preludes: harmonic similarities

Ex. 10. Froberger, Méditation, and Louis Couperin, unmeasured prelude: melodic and harmonic similarity

Ex. 11. Froberger, Méditation, upper parts in first measure

Ex. 12. Froberger, Méditation, scalar patterns in early measures

Ex. 13. Froberger, Méditation, passage borrowed from Toccata VI

Ex. 14. Froberger, Méditation, arpeggiated diminished fifth

Ex. 15. Froberger, Méditation, arpeggiated opening of second reprise

Ex. 16. Reference in Froberger, Méditation, to Froberger, Tombeau for Ferdinand III

Ex. 17. Froberger, Méditation, instances of repetition

Ex. 18. Froberger, Méditation, rhetorical figures in approach to the ending

Ex. 19. Froberger, Méditation, final measures

Figures

Fig. 1. Map of Héricourt, 1744, showing the castle north of the city

Fig. 2. Sibylla of Württemberg, as shown in the engraving on her casket

Fig. 3. Coat of arms on the bindings of Montbéliard Manuscript and A-Wn Mus. Hs. 18710

Fig. 4. Device of the Order of the Skull