The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 27 (2021) No. 1

Three Forged “Seventeenth-Century” Venetian Songbooks: A Cautionary Tale

Marica S. Tacconi*

[Things] are not always exactly what they seem:

Outward appearances are often deceptive,

And few are favored with a fine enough sense

To discover what the artist has concealed [within].

—Gaius Julius Phaedrus, first century CE[1]

Abstract

This study examines three Venetian songbooks that preserve solo songs and arias written by seventeenth-century Italian composers. While the manuscripts seem to be products of the Seicento, they are actually elegant forgeries, produced sometime between 1912 and 1916/17 and made to appear authentic. Considered in proper context, the manuscripts and their contents fit into the late-Romantic tradition of so-called “arie antiche” or “gemme antiche,” which saw music collectors, musicians, and audiences alike drawn to the “antiquity” of Italian Baroque solo vocal music.

2. Content and Appearance of the Manuscripts

5. Motive, Means, and Opportunity

1. Introduction

1.1 The Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana of Venice houses three beautifully produced manuscripts, preserving a number of solo songs and arias all written by seventeenth-century Italian composers. Surprisingly, they have received very little scholarly attention and, despite similarities in format and content, they have hitherto not been closely examined as a set. The three manuscripts are I-Vnm Codd. Italicum IV, 740 (=10313), 742 (=10318), and 743 (=10317), hereafter MS 740, MS 742, and MS 743. Collectively, they include a total of sixty-one compositions spanning the period from 1600 to 1678; the works are by as many as twenty-six Italian composers writing in a wide range of musical styles.

1.2 The three songbooks have been cataloged, listed, and cited as manuscripts produced in the Seicento.[2] The Biblioteca Marciana’s online catalog lists them as seventeenth-century items;[3] they also appear as seventeenth-century sources in the Catalogo nazionale dei manoscritti musicali, in passing references in several scholarly contributions, and as seventeenth-century manuscript concordances in a number of thematic catalogs.[4] However, my research has revealed that MSS 740, 742, and 743 were actually made in the early twentieth century, specifically sometime between 1912 and 1916/17. In short, they are fakes.[5] While the music they preserve is authentic, the actual books are the handiwork of one or more fabricators who, working with several scribes and decorators, went through extraordinary means to make the volumes appear genuine.

2. Content and Appearance of the Manuscripts

2.1 Although the three manuscripts were copied and decorated by different scribes and artists, they share similarities in content and format. All sixty-one songs and arias are for one voice and basso continuo with no indications of figured bass. The compilers provided the composers’ names and the titles of the works from which the excerpts were thought to be drawn. MSS 740 and 742 also give the dates of composition. The paper looks and feels authentic, showing some signs of deterioration and even the occasional worm hole. In all three cases, a study of the watermarks is inconclusive; perhaps intentionally, they are either absent or very partial. The musical notation, executed by a different scribe in each manuscript, exhibits traits that give it an “antiquated” feeling, including the use of sepia-colored ink and curved beams.

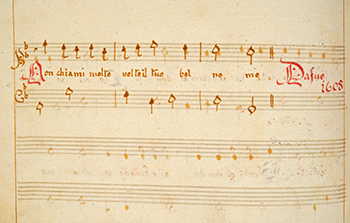

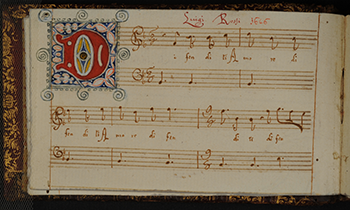

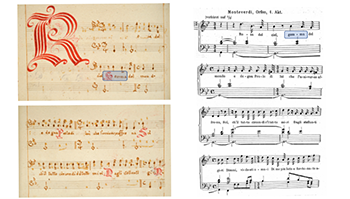

2.2 MS 740 includes twenty-four works attributed to thirteen composers, with compositions dating between 1600 and 1656 (see Table 1a).[6] The composers’ names are inscribed in large red letters at the outset of each piece or set of pieces (Figure 1), and the title and year of the work from which the excerpt is drawn is given at the end (Figure 2). The sixty-six paper folios (including five blank but ruled leaves at the end) are bound in leather with brass bosses on both top and bottom boards (Figure 3).

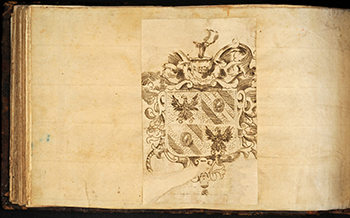

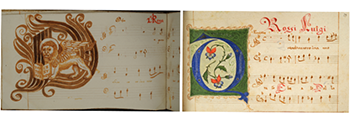

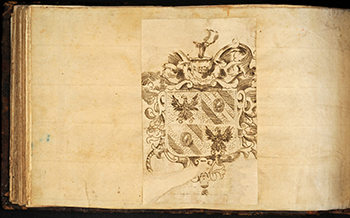

The codex is fairly small, measuring 13 x 22 cm; it is decorated throughout and was copied by a single hand with a propensity for triangular (heart-shaped) noteheads. The opening page is particularly striking: it shows a richly decorated initial T, the opening of Tu mancavi a tormentarmi (Figure 4), erroneously attributed to Antonio Cesti.[7] The bottom margin displays the coat of arms of the Contarini family, one of the most prominent and influential Venetian households. A different version of the Contarini shield appears again as an ex libris at the end of the manuscript (Figure 5); I will return to this later.

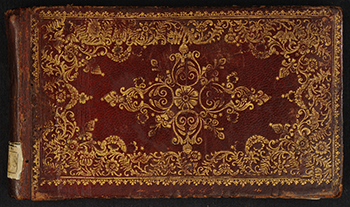

2.3 MS 742 includes eighteen works by sixteen composers, with pieces dating between 1602 and 1657 (see Table 1b).[8] The composer’s name, together with the year and title of the work from which the piece is extracted, is inscribed in red ink at the beginning of each entry (Figure 6). The codex comprises fifty-one paper folios (including three blank but ruled leaves at the end) bound in red tooled leather (Figure 7).

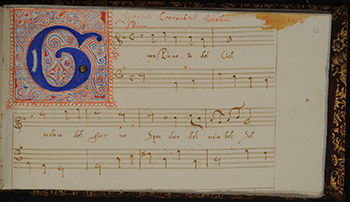

This book is smaller than MS 740, measuring 8.5 x 15 cm. It is copied by a single hand, but one different from that of MS 740. Its pages are richly decorated: fol. 1r displays an illuminated initial C that marks the opening of Claudio Saracini’s Canto dolce e soave (Figure 8). The openings of the other works feature capital letters that are ornately decorated in blue, red, and white, sometimes with a touch of yellow (Figure 9). The first flyleaf displays a bookplate that belonged to Caterina Dolfin (1736–93), a prominent and fascinating figure in late eighteenth-century Venice (Figure 10).

2.4 The third book, MS 743, preserves nineteen works attributed to nine composers, with pieces dating between 1611 and 1678 (see Table 1c).[9] As in the other two manuscripts, the composer’s name and the title of the work from which the aria is extracted are inscribed at the outset of each piece or set of pieces (Figure 11). However, unlike the other two manuscripts, here the date of composition is not given. Measuring 9 x 15 cm, the codex comprises sixty-seven paper folios in a red tooled leather binding that is almost identical to that of MS 742 (Figure 12). As many as seventeen pages are ruled but left blank at the end (fols. 59v–67v), which might indicate that the manuscript was left unfinished. MS 743 was copied by a single music scribe, but a different one from those who worked on the other two codices; as in MS 740, the noteheads are triangular, even heart-shaped. MS 743 is also copiously decorated. The first page shows a richly ornamented capital A, the opening of Cavalli’s aria “A portar di bella il vanto” from Le nozze di Teti e di Peleo (Figure 13). Perhaps even more striking, however, is the presence of the Contarini coat of arms surmounted by the Venetian doge’s hat; I will return to this later.

2.5 What does all of this physical and internal evidence point to? At first glance, and to untrained eyes, the books have the appearance of antique artifacts: the bindings, the yellowing paper, the decorative apparatus, the script, the musical calligraphy. More specifically, the coat of arms would seem to indicate a Venetian provenance, with MSS 740 and 743 originally belonging to the Contarini family, and MS 742 eventually coming into the possession of Caterina Dolfin. The unsuspecting viewer is led to regard these books as precious products connected to the relatively new interest in monody and the cantata, and to the Venetians’ particular love for public opera.

3. The Fakes

3.1 The Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana acquired the books from a Venetian bookdealer in 1916 and 1917, and they became part of the collection, cataloged as seventeenth-century sources. The creators of the three manuscripts had everyone fooled for quite some time. Lorenzo Bianconi, in 1972, was the first to cast doubt on the books’ authenticity, proposing a nineteenth-century dating, but the warning, inserted as a “marginal note” in a book review, went largely unnoticed by the scholarly community, and the fabricators’ deceit continued to go undetected.[10] While on the surface the books appear to be old, a closer look, and especially a careful examination of the music, reveals the deceit. First, a point of clarification. The sixty-one pieces they preserve were indeed all composed in the seventeenth century (see Table 1). They include many musical gems by composers associated with early monody and with a number of significant seventeenth-century operas and cantatas. Among the early monodies are solo songs and arias by the Florentines Jacopo Peri, Giulio Caccini, and Marco da Gagliano, drawn from landmark works such as the early Euridice operas (1600), Le nuove musiche (1602), and La Dafne (1608). Other early dramatic works are represented by selections from Emilio de’ Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo (1600), Agostino Agazzari’s Eumelio (1606)—one of the earliest Roman operas—and Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (1607). Composers represented by more than one song or aria include Giulio Caccini, Francesco Cavalli, Domenico Freschi, Stefano Landi, Giovanni Legrenzi, Domenico Mazzocchi, Claudio Monteverdi, Jacopo Peri, Luigi Rossi, and Antonio Sartorio.

3.2 This mishmash of composers and works appeared odd to me from the beginning. If the manuscripts were indeed produced in Venice in the late seventeenth century, it seemed strange that they would include compositions by Florentine early monodists, composers of early Roman opera, and other composers whose music had no association with Venice and its region. Other manuscript anthologies from seventeenth-century Venice are much more monographic in content and tend to focus on arias from operas premiered, or at least subsequently performed, in Venice.[11] Then there is the issue of sources. Many of the pieces were preserved in manuscripts outside of Venice or in prints that did not circulate widely. It seemed unlikely that any scribe in the seventeenth century would have had access to such disparate and wide-ranging material.

3.3 It is only when we carefully examine the music and its sources, however, that we have conclusive evidence that the manuscripts are indeed fraudulent. Let us first consider MS 740. All but one of its twenty-four works were copied from five late nineteenth- / early twentieth-century publications by Alessandro Parisotti, Hugo Goldschmidt, and Hugo Riemann (see Table 1a).[12] Perhaps most striking, the third through sixteenth entries in the manuscript were copied, in the same order, from examples found between pages 156 and 300 of the first volume of Goldschmidt’s Studien zur Geschichte (1901). A plausible assumption could be that MS 740 served as one of Goldschmidt’s sources. After all, we know that both he and Riemann drew upon some early manuscripts as sources for their musical examples. However, even closer examination of the music confirms that the scribe of MS 740 copied from Goldschmidt and the other modern books, not the other way around.

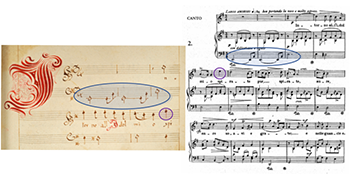

3.4 Margaret Murata, in her 1998 article “Four Airs for Orontea,” had already made a passing reference to MS 740 being “false.”[13] As Murata noted, the scribe of MS 740 copied Cesti’s “Intorno all’idol mio” from Orontea (fols. 6r–9r) directly from Parisotti’s first volume of Arie antiche, published in 1885.[14] Parisotti’s version of “Intorno all’idol mio” was taken from one published by Carl Banck a few years earlier.[15] Perhaps in an effort to “romanticize” the 1656 aria, Banck added a two-measure piano introduction characterized by a barcarole-like bass line. The scribe of MS 740 reduced the aria back to its solo vocal line over a basso continuo, but kept the barcarole-like bass line of the piano introduction and some of Parisotti’s added ornamentation (Figure 14).[16] There is also a wrong note in the vocal line: the last pitch in measure 5 (fol. 6r) should be an E, not a C—an error the scribe must have made in the process of copying from the treble clef of Parisotti’s edition and transcribing to C1 clef (Figure 14). Cesti’s aria is also present in MS 743 (fols. 6r–9v). This time, however, the scribe omits the two-measure barcarole-like bass line introduction but, again drawing from Parisotti’s edition, includes it between stanzas 1 and 2 and at the end (Figure 15).[17]

3.5 The fabricators of MS 742 and MS 743 were more shrewd in making their handiwork appear authentic. The inclusion of works in MS 740 in the same order found in Goldschmidt’s Studien zur Geschichte could have raised suspicion in the eyes of anyone familiar with the 1901 publication. MS 742 does away with that sort of wholesale lifting of material, interspersing compositions copied from Riemann, Goldschmidt, and Eitner (see Table 1b).[18] Finally, the fabricators of MS 743 relied on modern publications to a much lesser extent, copying several works from seventeenth-century manuscripts at the Marciana and Querini Stampalia libraries (see Table 1c). Again, close musical analysis provides the most conclusive evidence that MSS 742 and 743, like MS 740, were produced in the early twentieth century.

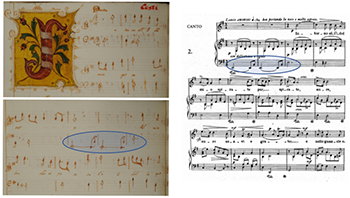

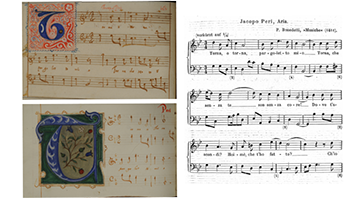

3.6 By way of example, let us consider Jacopo Peri’s monody Torna o torna pargoletto, present in both MSS 742 and 743 (fols. 25v–28r; fols. 37v–41r). The song is found in Riemann’s Handbuch (pp. 31–32), which names the source for the transcription: Piero Benedetti’s Musiche, published in Florence in 1611—a collection of twenty-two monodies, all by Benedetti except for the song by Peri and one by Marco da Gagliano.[19] Benedetti’s print is the only known seventeenth-century source for Peri’s monody.[20] A comparison between Benedetti’s print and Riemann’s version reveals some small but significant variants, however. The opening in Benedetti’s print reads “Torna deh torna pargoletto,” while Riemann has “Torna o torna.” A few measures later, the 1611 print text reads “che t’ho fatt’io,” while Riemann has “che t’ho fatto” (Figure 16). Most striking, however, is the change in metric organization, from Benedetti’s C 3/2 starting on the downbeat to Riemann’s 3/4 starting on the second beat (Figure 16). Riemann specifically discusses this change, which, as he explains, he made in an effort to achieve clearer text declamation.[21] MSS 742 and 743 include all of Riemann’s variants (Figure 17); there is no doubt, therefore, that the scribes of both manuscripts used Riemann, and not the 1611 print, as their source.

3.7 Metric shifts of the type seen in Riemann’s edition of Peri’s Torna are found systematically throughout his Handbuch, and are all consistently preserved in the three manuscripts in the works copied from the 1912 publication.[22] Another example is Riemann’s transcription of Alessandro Grandi’s cantata Vanne vattene Amor. Here too Riemann indicates the source of his transcription: Grandi’s Cantade et arie a voce sola (Venice, 1620).[23] As in his transcription of Peri’s Torna, Riemann again alters the meter, from the original common time (C) to a peculiar rearrangement of measures notated in 3/4, 2/4, and 3/8. These curious metric shifts are preserved in MS 742 (fols. 28r–29v), clearly indicating that the scribe was copying from Riemann’s 1912 Handbuch and not from the 1620 print. One further example is Monteverdi’s well-known aria “Rosa del ciel” from L’Orfeo. Riemann’s version constantly shifts between 3/4 and common-time (C) meters, an oddity that the scribe of MS 740 preserves (fols. 39v–42r).[24] Incidentally, the scribe also keeps Riemann’s textual variant: “Rosa del ciel, gemma del mondo,” instead of the standard “vita del mondo” of the opera’s 1609 printed score (Figure 18).

3.8 The first three entries of MS 743 appeared, in the same order, as the opening three items in a collection of twenty arias edited by Maffeo Zanon, published in 1908 as part of the Tesori musicali italiani series (see Table 1c).[25] The fabricator of MS 743 seems to have copied the three Cavalli arias from Zanon’s publication, stripping them of the realized basso continuo accompaniment and the editorial marks added by Zanon.[26] Zanon’s preface states that the pieces were copied from Venetian sources, a point he elaborates upon in a second collection of twenty-four arias (Raccolta di 24 arie) issued in 1914. It is worth considering the preface of this later collection for what it reveals:

The twenty-four arias of this collection were drawn exclusively from the music codices of the Contarini Collection, found in the Biblioteca Nazionale di S. Marco in Venice. I find it essential to state this, so that the great artistic and historic importance of these precious 17th-century manuscripts can finally be recognized; even though they have belonged for 70 years (1843) to a public library, we can say that they are still completely unknown. About 25 years ago the complete catalog was published;[27] although it is excellent, it can only satisfy bibliophiles or perhaps musicologists, but not musicians nor art lovers, who must limit their knowledge of this or that opera, or of this or that author…. Very little has been edited so far of these 120 volumes, almost all of which are unique exemplars; only one was published in its entirety (“L’Incoronazione di Poppea” by Claudio Monteverdi) … and for the others, with the exception of a few brief excerpts (“Arie antiche” collected by A. Parisotti – Ricordi edition), we have, until now, only two collections of arias, both done by me.[28]

None of the arias of Zanon’s 1914 collection is included in the forged manuscripts, but its preface may well have provided inspiration for the production of MS 743. Perhaps following Zanon’s prescription, the fabricator of MS 743 turned indeed to three, maybe four,[29] “precious 17th-century manuscripts” as the source for eight of its entries (nos. 4–7, 11–14).

3.9 Numbers 4–6 are three arias from Cavalli’s Erismena copied from I-Vnm Cod. It. IV. 417. The Marciana library preserves an additional manuscript of Cavalli’s Erismena (I-Vnm Cod. It. IV. 360), but the musical material in MS 743 was copied from I-Vnm Cod. It. IV. 417. Especially revealing is the Act I aria “Faville d’amore” (no. 4), which appears in versions with different bass lines in I-Vnm Cod. It. IV. 417 (fol. 7v) and I-Vnm Cod. It. IV. 360 (fol. 5v). The version in MS 743 (fols. 7r–8r) is identical to that in I-Vnm Cod. It. IV. 417.

3.10 Two arias by Domenico Freschi (nos. 11–12) and Antonio Sartorio (nos. 13–14), respectively, were copied from two seventeenth-century manuscripts preserved at the library of the Fondazione Querini Stampalia: I-Vqs Ms. Cl. VIII.4 (1430) and I-Vqs Ms. Cl. VIII.5 (1431). Consider, for example, Freschi’s “Gelosia non posso più” from Helena rapita da Paride (no. 11). The Act 1, scene 4 aria exists in two versions: “Gelosia non posso più tormentarmi” in C minor and “Gelosia non tormentarmi” in F major. The C minor version preserved in MS 743 is the same found in Querini Stampalia MS 1430, which is the only known seventeenth-century source for this particular version of the aria.[30]

3.11 The inclusion of Legrenzi’s “Lasciami in pac’il core” from Eteocle e Polinice (Act 1, scene 14) deserves special mention (see Table 1c, MS 743, no. 8). The aria, sung by Tideo, exists in two versions, one (more common) in A major and the other in D major. The version present in MS 743 is the one in D major, which appears to be found in only one other source, an Oxford, Christ Church Library, manuscript copied by an Italian scribe in the last quarter of the seventeenth century (GB-Och Mus. 945, fols. 22r–23v).[31] Small musical differences, however, suggest that the Christ Church manuscript was not the exemplar for the Legrenzi aria in MS 743.[32] Instead, the aria seems to have been copied from Riemann’s Musikgeschichte in Beispielen (1912), where it is also present in its D major version.[33]

3.12 For the remaining seven entries in MS 743—nos. 9–10 (fols. 17v–27r) and nos. 15–19 (fols. 37v–59r)—the fabricator duplicated material included in the other two songbooks, all taken from Parisotti’s Arie antiche, Riemann’s Handbuch, and Goldschmidt’s Studien (see Table 1). There is evidence to suggest that the scribe copied these items directly from MSS 740 and 742. Consider, for example, the sixteenth entry of MS 743—Luigi Rossi’s “Quando un core inamorato” [sic] from Orfeo.[34] The decorator mistakenly marked the opening of the aria with a large calligraphic initial D (fol. 41v), thus forcing the scribe to alter the text of the aria to “Da quando un core,” instead of the standard “Quando un core” present in MS 740 (fol. 29r) (Figure 19).[35] The decorator’s error is likely the result of the ambiguous shape of the initial Q in MS 740, which he must have used as the exemplar. With its ornamental serif in the upper left, it was easily confused for a D. Perhaps in the spirit of Zanon’s preface, the fabricator of MS 743 set out copying from seventeenth-century manuscript sources but eventually, possibly running out of time, turned to MSS 740 and 742 to quickly add more material.[36]

3.13 From a visual standpoint, the fabricators of MS 740 almost tried too hard to make their handiwork look old. There are anachronistic elements that point to an effort to medievalize the book: the heavy leather binding with its brass bosses, the numerous large, illuminated initials and their bold color palette, the gothic lettering marking the composers’ names. While these elements may have bestowed the manuscript with an air of antiquarian historicity in the early twentieth century, they do appear odd to expert viewers today. With the exception of the opening folio with its richly ornamented initial C, the decorative apparatus of MS 742 is much simpler. The tooled leather binding appears to be, indeed, from the seventeenth century, likely lifted from another book and repurposed. The same type of binding is affixed to MS 743, but the book does, again, include four illuminated initials (fols. 13r, 17v, 37v, 54v), similar to those present in MS 740 (Figure 20).

3.14 The other decorative letteroni are drawn in ink and are of a highly ornamented calligraphic type that had been designed and popularized by Vespasiano Amphiareo (1501–63), a sixteenth-century Franciscan friar from Ferrara, active in Venice. The fabricator must have had access to one of Amphiareo’s calligraphy manuals, as he closely reproduced not only the general style, albeit somewhat simplified, but also some of the specific decorative elements of the manuals’ elaborate engravings—putti, grotesque faces, birds.[37] Most striking is the capital letter L on fol. 32r, the opening of the aria “L’alma mi brilla” from Sartorio’s Anacreonte tiranno. Here the scribe reproduced not only the overall shape and style of Amphiareo’s letterone, but also details such as the long-beaked bird on the tail of the letter and the signature scroll with the inscription “Frater Vestastanus” (i.e., Brother Vespasiano) (Figure 21).[38] The inclusion of these details shows that the fabricator copied directly from one of Amphiareo’s manuals, which would still have been readily available in early twentieth-century Venice.

4. Deceiving the Experts

4.1 The Marciana Library bought the fakes in 1916 (MSS 740 and 742) and 1917 (MS 743). Therefore, we can conclude that they were produced sometime between 1912—the date of Riemann’s Handbuch and Musikgeschichte in Beispielen—and 1916/17. In the case of MS 743, if the Preface of Zanon’s 24 arie (1914) indeed influenced its creation, then we might narrow the time of production to 1914–17. Clearly, the scribes and decorators who worked on the books were different, but there is some evidence to suggest that a single mastermind was behind the manuscripts’ fabrication, and that they were designed with the Biblioteca Marciana in mind as the potential buyer.

4.2 The presence of the Contarini coat of arms in both MSS 740 and 743 would certainly have piqued the Marciana’s interest in the books’ acquisition. After all, by way of a bequest from Girolamo Contarini (1770–1843), the Library had acquired in 1843 the family’s entire collection, which includes 956 manuscript scores and nearly 4700 printed books. Among these are 112 scores of operas and other forms of dramatic music; they represent some of the most important sources for seventeenth-century Venetian opera, including manuscripts of operas by Monteverdi, Cavalli, Cesti, and Sartorio, among many others, as well as a large number of the original printed librettos.[39] Most of the music manuscripts and printed librettos came from the collection of one of Girolamo’s most illustrious ancestors, Marco Contarini (1632–89)—a Venetian nobleman and Procurator of Saint Mark—who in the 1660s had built two theaters on his grand country estate, Piazzola sul Brenta, located on the mainland about thirty miles west of Venice. The larger of the two theaters, comprising 1000 seats, was specifically designed for opera, with a number of works especially commissioned by Marco Contarini.[40] The Venetian nobleman had also established an orphanage on his estate, known as the “Luogo delle Vergini.” It was no doubt modeled on the Venetian Ospedali; the thirty girls were musically trained and their talents were regularly on display through chamber performances in the smaller, 400-seat theater.[41]

4.3 As mentioned previously, two of the three books display the Contarini coat of arms. The first folio of MS 740 shows the basic heraldic element of the family crest: a gold shield with diagonal azure bands (Figure 4). The ex-libris affixed at the end of the manuscript specifically belonged to Marco Contarini (Figure 5). The shield is divided into quadrants—two with the family’s traditional diagonal bands and a central fleur-de-lis, and two displaying a crowned eagle.

The same coat of arms is present in many of the printed librettos for operas Marco Contarini commissioned for his theater. One such example is the libretto by Francesco Maria Piccioli for Le Amazoni nell’isole fortunate, set to music by Carlo Pallavicino and premiered in 1679 for the inauguration of the large Piazzola theater.[42] Marco Contarini’s coat of arms is printed on the reverse of the title page; it is identical to the one in MS 740. The fabricator of the manuscript must have had access to one of the Piazzola opera librettos, excising the coat of arms and affixing it to MS 740 with the intent of making the book seem like one belonging to Marco Contarini.

4.4 The Contarini coat of arms painted on fol. 1r of MS 743 is surmounted by the corno dogale, the curiously shaped hat traditionally worn by the Venetian doge (right-hand side of Figure 13).

Here the manuscript’s fabricator likely wanted the viewer to believe that the book was made at a time when Venice was under Contarini ducal authority. Domenico II Contarini (1585–1675) and Alvise Contarini (1601–84) served as doges in the second half of the seventeenth century, from 1659 to 1675 and 1676 to 1684, respectively—years that overlap with much of the manuscript’s musical content. However, the coat of arms painted in MS 743 is not the one adopted by either Domenico or Alvise.[43] Instead, the decorator reproduced Marco Contarini’s shield and added the corno dogale. Any seventeenth-century Venetian viewer would have noticed the incongruity, but by the twentieth century the deceit went unnoticed. The forger’s inclusion of the ducal arms was likely a way to bestow value upon the manuscript—a book that was intended to be perceived as circulating in the highest circles of seventeenth-century Venetian society. Likely due to the presence of the Contarini coat of arms, MS 743 has erroneously been cited as belonging to the Contarini collection.[44]

4.5 In the case of MS 742, the fabricator led us to believe that, at some point in the late eighteenth century, the book was owned by Caterina Dolfin (1736–93), whose ex libris appears on the opening flyleaf (Figure 10).[45]

Here too the apparent association with the Venetian noblewoman would have elevated the book’s prestige. The forger may also have wanted to entice the Marciana Library to acquire the manuscript, as its collection included Dolfin’s book of sonnets, published in 1767 in memory of her father.[46] Caterina Dolfin was married to Andrea Tron, a descendant of the family that, back in 1637, had established the first public opera house, the Teatro San Cassiano. A highly cultured woman, Caterina was also the host of a prominent literary salon in the parish of San Zulian (San Giuliano).[47] The fabricator may have wanted the viewer to think that the book originated in the seventeenth century in the operatic circles of the Tron family, eventually finding its way to Caterina Dolfin’s intellectual soirées.

5. Motive, Means, and Opportunity

5.1 Forgery is a kind of crime, and like any crime, whether human or pertaining to books, it involves motive, means, and opportunity. Who might have commissioned these fakes? We will likely never know for sure, but we can at least offer a few insights and venture into some speculation. Acquisition records show that the Marciana Library bought the three manuscripts from the same dealer, a Venetian organist and composer by the name of Giovanni Concina (1869–1946). The letterhead stationery used for his invoices reads “Giovanni Concina – Musica – Venezia,” suggesting that he was the owner of a music shop or music book dealership in Venice. Indeed, Concina sold numerous music manuscripts to the Marciana, starting with a first large nucleus of 152 items in 1915, followed by more sporadic sales until 1929.[48] A page of the registry listing Concina’s 1915 sales to the Marciana includes 31 musical items with prices ranging between 0.30 and 18 Italian lire, equivalent to $1.30–$80 in today’s currency.[49] By contrast, MS 742 was sold for 62 lire, approximately $220 today—an indication of its relative value.[50] Concina’s invoice to the Biblioteca Marciana, dated 30 September 1916, reads: “Musical manuscript containing arias by seventeenth-century masters, bound ex libris Dolfin. Lire 62.”[51] Although the invoices for MSS 740 and 743 appear not to have survived, we can assume that they were likely sold for a similar price. We know of at least one other fabricated music manuscript sold by Concina to the Marciana in 1917, a basso continuo treatise dated 1664, but actually a forgery, possibly also made in the early twentieth century.[52]

5.2 It is impossible to know whether Giovanni Concina was aware of the forgeries. Did he come into possession of the books with no knowledge of their fabricated nature, or was he aware, perhaps even involved, in the deceit? In 1914 Concina had published a catalog of the musical holdings of four Venetian libraries, including the Biblioteca Querini Stampalia and the Biblioteca Marciana.[53] This work would have given him direct access to these collections and to the exemplars for the arias in MS 743 drawn from manuscripts preserved in those libraries. Moreover, as a musician and owner of a music book shop or dealership, he likely would have come across the publications by Parisotti, Goldschmidt, Riemann, and others. He also would have had access to the materials that made the manuscripts look antique: their leather bindings, the Contarini and Dolfin ex libris excised from other books, and perhaps even the old yellowing paper. Concina would have had means and opportunity. Although in the realm of conjecture, it is possible that he served as the mastermind behind the fabrication of the three songbooks, coordinating their production and profiting from their sale. By 1916 Concina had established himself as a regular and seemingly trusted seller to the Marciana, providing a steady stream of music items.

5.3 The progressive level of deceit in the fabrication of the three manuscripts—from wholesale lifting of a segment of Goldschmidt in MS 740 to a mingling of sources, including manuscripts, in MS 743—might shed light on the motive behind their creation. Monetary gain was probably not the main impetus. While it is true that, relatively speaking, the three manuscripts were likely all sold for much more than Concina’s other sales to the Marciana, 62 Italian lire (ca. $220)—the price paid for MS 742—was still a fairly modest sum. Instead, what we have is possibly an example of the fabricators, or more likely the mastermind behind their creation, engaging in a desire to “hoodwink the experts.”[54] As Frederick Reece has concluded in his discussion of a well-known musical forgery involving a set of six “Haydn” keyboard sonatas, “one possible justification is the sheer pleasure to be gleaned from immersing oneself in—and recreating—a beloved historical idiom.”[55] In this case, the “beloved historical idiom” is the repertoire of songs and arias from the Seicento. Unlike most other examples of music forgeries, however, here the music is authentic, albeit with its late-nineteenth / early-twentieth-century editorial quirks.[56] Instead, the deceit rests in the way the works were “anthologized,” grouped in books that were specifically designed to appear as products of seventeenth-century Venice. In content, they are essentially the manuscript versions of the printed sets of Italian songs that were popularized by Parisotti’s Arie antiche, Zanon’s Arie, and the like. They fit into the late-Romantic tradition of so-called “arie antiche” or “gemme antiche,” which saw music collectors, musicians, and audiences alike drawn to the “antiquity” of Italian Baroque solo vocal music.[57]

5.4 As Anthony Grafton has argued, love—for the craft, for the artifact, for the repertoire—is often the preeminent motive in the act of forgery.[58] The painstaking crafting of these books—the rich decorative apparatus, the elegant musical notation and script, the composers’ names boldly inscribed at the outset of the pieces—shows the care, the “love” behind their creation. And yet, if we look carefully enough, once we lift the veil of deceit, the simulation of the past reveals its flaws. Again, in the words of Anthony Grafton:

If any law holds for all forgery, it is quite simply that any forger, however deft, imprints the pattern and texture of his own period’s life, thought, and language on the past he hopes to make seem real and vivid. But the very details he deploys, however deeply they impress his immediate public, will eventually make his trickery stand out in bold relief, when they are observed by later readers who will recognize the forger’s period superimposed on the forgery’s. Nothing becomes obsolete like a period vision of an older period.[59]

Indeed, the fabricators superimposed their own early twentieth-century culture and artistic preferences onto their vision of the Seicento. That vision included what they considered to be antique elements: the old binding with brass bosses of MS 740 (Figure 3), the medievalizing illuminated initials (Figure 1; Figure 11), the varied decorative elements in the antiqued letteroni. At the same time, it also included the romanticized barcarole bass of Cesti’s Intorno all’idol mio and the mixed meters of Riemann’s Handbuch—all features they perceived as congruous with the musical past they tried to recreate and pass off as genuine. What seemed “Baroque” to them seems markedly late nineteenth / early twentieth century to us, at least once our blinders are removed.

5.5 The decorative apparatus of the manuscripts afforded the fabricators an opportunity to do what the printed collections of “arie antiche” could not: it responded visually to a predominant aesthetic principal—that of elegance. Many of the editors of the anthologized “gems” selected them for their “elegance,” to which they refer almost obsessively. For Alessandro Parisotti, Francesco Cavalli “gave the aria greater freedom and elegance of form,” Alessandro Scarlatti’s “flowing style is united with elegance,” and a cantata by Gasparini is described as having “efficacious elegance.”[60] For Luigi Torchi, the compiler and editor of the appropriately titled Eleganti canzoni ed arie italiane del secolo XVII, Biagio Marini is a composer of “original and elegant” songs for one voice, Andrea Falconieri is an “ingenious and elegant musician,” Bernardo Gaffi is a composer of “elegant cantatas,” and Giovanni Legrenzi is a “pure and elegant designer of melodies.”[61] The three Marciana songbooks carry this concept beyond the musical selections, displaying the fabricators’ view of “eleganza” in the decorated initials, the antiqued inscriptions with composers’ names and works’ titles, and perhaps even in such details as the heart-shaped noteheads of MSS 740 and 743.[62] The result is a pastiche of many incongruous and ahistorical elements.

6. Epilogue

6.1 The three Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana songbooks represent a cautionary tale. Seemingly authentic on the surface but fraudulent at their core, they remind us that appearances can be deceiving. At first glance, the bindings, the antiqued decorative apparatus, and the musical content can lead us to believe that they were, indeed, made in the late seventeenth century. Does it matter that they were not? If the music they preserve is indeed from the Seicento, what difference does it make if they were actually produced in the early twentieth century? It does matter, because if we view them as authentic products of seventeenth-century Venice, we gain a distorted view. We could conclude that songs and arias of the Seicento circulated more widely than previously thought; we could surmise that Florentine and Roman composers were already popular in seventeenth-century Venice; or we could think that the books’ specific content—the choice of composers and pieces—reflects seventeenth-century musical taste. To spin off Phaedrus’s wise words, “things are not always exactly what they seem,” so look closely, do not be fooled by appearances and, as scholars, do your research.

Acknowledgments

Research for this project began in Fall 2018 while I was on research sabbatical in Venice. The sabbatical was supported by a faculty research grant from the College of Arts and Architecture at the Pennsylvania State University and by a James E. Hess and Suzanne Scurfield Hess Endowment Grant. I am grateful to Ivano Zanenghi for introducing me to some of his former colleagues at the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana of Venice. Soprano Liesl Odenweller, harpsichordist Marija Jovanovic, and other members of the Venice Music Project ensemble (https://www.venicemusicproject.it) performed selections drawn from the three manuscripts as part of lecture-recitals held in Venice (June 2019) and University Park, Pennsylvania (November 2019). This article is an expanded version of a paper presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Musicological Society (Boston, Massachusetts). A number of scholars offered insights during the research phase and provided helpful suggestions as the paper developed into the article. I would particularly like to thank Margaret Murata, Frederick Reece, Ellen Rosand, and Daniel Zolli. I am also indebted to several colleagues and to the staff of libraries at various institutions for their valuable assistance as materials became difficult to access during the partial lockdowns of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thanks are especially due to Lorenzo Bianconi, and to the staff of the Interlibrary Loan department at Penn State’s Pattee and Paterno Libraries, to Judith Curthoys and Alina Nachescu of the Christ Church (Oxford) Library staff, and to Luciana Battagin and Susy Marcon of the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana. The two anonymous JSCM readers offered suggestions that greatly improved the article. Finally, I am grateful to editor-in-chief Lois Rosow for her guidance, expert comments, and keen editorial eye.

Figures

Fig. 1. MS 740, fol. 42v

Fig. 2. MS 740, fol. 44v

Fig. 3. MS 740, binding, top board

Fig. 4. MS 740, fol. 1r

Fig. 5. MS 740, flyleaf with Contarini ex libris

Fig. 6. MS 742, fol. 16r

Fig. 7. MS 742, binding, top board

Fig. 8. MS 742, fol. 1r

Fig. 9. MS 742, fol. 3v

Fig. 10. MS 742, flyleaf with Caterina Dolfin ex libris

Fig. 11. MS 743, fol. 13r

Fig. 12. MS 743, binding, top board

Fig. 13. MS 743, fol. 1r

Fig. 14. Cesti, “Intorno all’idol mio” from Orontea: MS 740 and Parisotti, Arie antiche

Fig. 15. Cesti, “Intorno all’idol mio” from Orontea: MS 743 and Parisotti, Arie antiche

Fig. 16. Peri, “Torna, o torna pargoletto”: Benedetti, Musiche, and Riemann, Handbuch

Fig. 17. Peri, “Torna, o torna pargoletto”: MS 742, MS 743, and Riemann, Handbuch

Fig. 18. Monteverdi, “Rosa del ciel” from L’Orfeo: MS 740 and Riemann, Handbuch

Fig. 19. Rossi, “[Da] quando un core inamorato” from Orfeo: MS 743 and MS 740

Fig. 20. MS 740, fol. 29r, and MS 743, fol. 37v

Fig. 21. MS 743, fol. 32r

Table

Table 1. Musical content of the manuscripts