The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 29 (2023) No. 1

Who Wrote Froberger’s Toccata XX?

Questions of Author Attribution in Early Keyboard Music

Alexander Silbiger*

Abstract

In early solo instrumental music, the links between composers’ names and their works are easily broken. A composition may be transmitted without any name attached, or with an incorrect one. As a case study, the transmission of a work known as Toccata XX by Johann Jacob Froberger, and widely accepted in the canon of his keyboard works, is examined. This work is included in eight early sources, none of them central to Froberger. In four of those it appears anonymously, whereas in the other four it is credited to three different composers. Since the evidence is not sufficient to attribute it securely to anyone among them, we should consider Toccata XX a work of uncertain authorship, perhaps “from the school of Froberger.”

1. The Links between a Composer and His Works in Froberger’s Time

2. Froberger’s Control of His Compositional Output

3. The Role of the Posthumous Publications in the Dissemination of Froberger’s Works

4. What the Sources of Toccatas XIX and XX Tell Us

5. Does the Music Provide the Answers?

1. The Links between a Composer and His Works in Froberger’s Time

1.1 While the keyboard composition now generally known as Johann Jacob Froberger’s Toccata XX contains some fine, even exciting music, I have always wondered whether it was really written by Froberger.[1] My uncertainty about the link between the composer and the piece led me to reconsider the entire basis for attributing a keyboard work to Froberger (or for that matter, to any other composer of his time) as well as to reassess the principal sources for his music, in the hope of thus arriving at a better position to address questions regarding the authorship of this specific composition.

1.2 The use of “wrote” in the question in my title implies a work created within a notated music practice. Only within such a practice is the identity of the creator likely to be of major interest. In early-modern Western culture, the practice of linking the name of a composer to a notated piece of music became gradually more common, most often by inserting it at the beginning or end, or in the case of a collection of works by the same composer, at the beginning of the entire collection. In identifying a work of music, the composer’s name was at least of secondary if not of equal significance to its title. It is no coincidence that when in the twentieth century a fully notated score becomes less central to a work’s identity or is altogether absent, as often is the case within popular culture, the composer’s name recedes in importance in comparison with, say, the name of the “song” (usually the beginning of its lyrics), performer(s), performing ensemble, and album. This devaluing of the composer’s name is evident to anyone using music streaming services such as Apple Music™ or Spotify™.

1.3 In earlier centuries, the link between a notated composition and its creator depended primarily on the written documentation provided by the score, and this link was easily broken once the work left the composer’s neighborhood. As happened frequently, a copy might be made omitting their name, or another name was substituted. Composers like Lasso, Schein, Schütz, and Hammerschmidt expressed their distress over the misattributed or anonymous circulation of their works, as well as over the circulation of corrupt versions.[2] They felt this posed a threat to their moral ownership of the works, to their control of the manner of performance, to the economic profits from sales, and in the case of music falsely attributed to them, to their reputations. Johann Caspar Kerll, for example, complained in the preface to a collection of his keyboard works, the Modulatio organica, that he had seen “and not just in one place, my works ascribed to other names.”[3] This was no idle claim, because contemporary manuscripts contain works of his credited to Frescobaldi, Froberger, and Poglietti. Although the named composers surely were not responsible, Kerll hoped to counter such theft and establish his authorship by appending to that publication the incipits of twenty-five of his keyboard compositions––in effect the first published thematic catalog of a composer’s works. In the same preface he condemned the practice of meddling with the text of his works: “I wish here to admonish organists not to subject the themes to their own whims, manipulating them as they please. Food properly cooked is bad when cooked again.”[4]

1.4 The link between score and composer was especially fragile for solo instrumental music. By the beginning of the seventeenth century, notated music––usually in the form of sets of partbooks––had become nearly indispensable for vocal and instrumental ensemble performance but played a less central role in solo performances. Many professional instrumentalists did not play solos from scores but instead relied on memory and improvisation. They might occasionally jot down some ideas or sketches or write out compositional models or exercises for their aspiring students, but they were not likely to attach their name to such a compositional sketch or exercise. In fact, they might have been quite annoyed if they learned that such materials were copied and distributed outside their circle of students and assistants, and even more upset if they knew that centuries later those pieces would be published, if not canonized with their names attached. Nevertheless, that is exactly what happened. Their followers treated these scores as sacred relics, to be collected, copied, and preserved. There is no better example than the large collection of the so-called “Chigi manuscripts” in the Vatican library associated with Girolamo Frescobaldi and his circle.[5]

1.5 Although teaching, especially to children and amateurs, was mostly by rote, some prominent musicians did take the trouble to write out and even publish compositions similar to those they performed. Often such works were targeted at wealthy or noble amateurs who lacked the skill to compose or improvise themselves but desired to play music of celebrated masters––or at least to possess some tangible records of their performances. Sometimes such masters also wrote a few pieces for the benefit of less skilled church organists. However, the need of those organists for short and simple pieces to be used during various parts of the service throughout the liturgical year was mostly met by copying and collecting suitable compositions––or more often sections of compositions––wherever those could be found. Such preserved utilitarian collections of versets often show little concern about the identity of the composer or the faithfulness of the copied texts.

2. Froberger’s Control of His Compositional Output

2.1 In a world in which few music lovers, whether dilletantes or professional colleagues, had the opportunity to hear a legendary musician like Frescobaldi or Froberger perform, there was great demand for scores of their works, to be studied, played, or just owned. Frescobaldi tried to meet that demand by publishing a series of collections of carefully prepared music in a wide range of representative genres. It was, however, not easy to render the works in print, thanks to their new flamboyant and quasi-improvisational style. The most common technique for music printing during the period, movable type, did not lend itself to the rhythmic nuances and voicing intricacies of this new style, despite occasional attempts such as those of the short toccatas in Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali.[6] Even with the more subtle technique of engraving on copper plates, it remained difficult to properly realize the scores without knowing how the composer performed them. Since Frescobaldi did not want to have the performance of his compositions limited to those with whom he had personal contact, he accompanied his publications with lists of instructions on how to execute his music.

2.2. Froberger seems never to have followed his teacher’s example of making his works available in print. Was it simply lack of opportunity, restrictions imposed by his patrons, or did he worry that without personal example or instruction, players would not know how to make musical sense of his scores?[7] Princess Sibylla of Württemberg, whose patronage he enjoyed during his final years, refused requests for copies of his music after he passed away because, she wrote, the composer felt that musicians not familiar with his way of performing them “did not know what to do with them, but only spoil them.”[8]

2.3 Fortunately for posterity, Froberger did make copies of some compositions available to a limited public of patrons, colleagues, and friends, who evidently treasured and preserved them, and sooner or later copies began to trickle out to larger circles of collectors and musicians. (See Appendix 2 for fuller citations of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century sources identified here only by short titles.) Among the most precious of the surviving collections of his works are the four autographs prepared for his patrons: the Libro Secondo (1649) and Libro Quarto (1656) for Emperor Ferdinand III, the Libro di Capricci (ca. 1658) for Emperor Leopold I, and the recently surfaced Montbéliard MS probably for Princess Sibylla.[9] These collections date from the time when the composer was a youthful thirty-three to his final years, and between them they contain nearly eighty compositions.[10] The three earlier autographs, now in the Austrian National Library in Vienna, presumably resided in the imperial library,[11] while nothing is publicly known about the history of the Montbéliard MS prior to it being offered for auction by Sotheby’s.

2.4 In only a few other cases can the survival of a score be traced to a direct personal connection. A complete version of Froberger’s Fantasia I is included as an example in the Musurgia Universalis (1650) of Athanasius Kircher,[12] with whom the composer had contact both in person and through correspondence;[13] two pieces appear in the Hintze MS in the hand of Froberger’s friend and colleague Matthias Weckman (ca. 1616–1674),[14] most likely sent to him by their composer in 1660 or thereafter;[15] and an expanded version of the first Ricercar from Libro Quarto found its way into François Roberday’s Fugues et Caprices (Paris, 1660) as Fugue 5, which Roberday is thought to have received from Froberger during the latter’s visit to Paris in 1660.[16] I will refer to the four autographs, along with the three sources apparently stemming directly from the composer, as Froberger source Group A. The sources in this group, and in the other two groups to be defined shortly, are listed by short title in Appendix 2.

2.5 A substantial number of Froberger’s works survive in a group of manuscripts dating, if not from his lifetime, at least from the decades immediately following his death in 1667. These manuscripts, which include SA 4450, Bauyn, Bulyowsky, and Minoriten 743, share a lot of repertory and exhibit other features that make them seem trustworthy, even if we generally are in the dark about how precisely their scribes obtained Froberger’s works. Their association with Froberger is virtually never challenged by conflicting attributions elsewhere. They tend to offer similar, if not always entirely identical readings of the pieces they share,[17] and often are notated in a manner resembling the Froberger autographs. Nevertheless, none appear to have been copied from the Group A autographs, which evidently were not available for this purpose. Many works in these manuscripts include performance instructions (such as avec discrétion) and sometimes quite lengthy biographical annotations. These annotations are usually not word-for-word identical with each other even when telling more or less the same story, which suggests that they may have been based on oral commentary Froberger provided when offering the pieces, or even while playing them.

2.6 For reasons to be explained shortly, I want to include among these sources the so-called “Fughe e Capricci” MSS, a set of four closely related manuscripts now in the Berlin Staatsbibliothek, containing contrapuntal works in open score. Although all date from the later eighteenth century and have been associated with the circle of J.S. Bach’s sons and students, they contain related repertory and offer reliable texts that most likely stem from Froberger.[18]

2.7 The entire repertory shared by these manuscripts, which I shall call Froberger source Group B, includes approximately fifty works, hence only somewhat smaller than that of Group A. However, the two repertories overlap by only some twenty works—perhaps fewer than one might expect. For certain genres it is even smaller. For instance, only two of the twelve Group A toccatas appear in the Group B manuscripts and none of the capriccios; most of the common works are dances.[19] The readings confirm that the shared pieces were generally not copied from the autographs, which, as noted earlier, most likely were not accessible for copying during Froberger’s lifetime and the years thereafter.[20] The pieces in the Group B sources probably stem from manuscript collections that remained in the composer’s possession and from which during his travels he would occasionally share pieces with friends and colleagues, perhaps in exchange for other favors.

3. The Role of the Posthumous Publications in the Dissemination of Froberger’s Works

3.1 The works that Froberger had passed on to friends and patrons were copied and copied again, but this did not begin to meet the eager desire for scores of his compositions, which after the composer’s death even grew in intensity. When available supply proved inadequate, other pieces that showed a somewhat credible resemblance to the master’s compositions had his name grafted onto them. Some may have been specifically created for that purpose, but even if that was not the case, one can well imagine that the temptation to greatly increase the value of a score, whether economic or sentimental, by simply inserting a famous name at its beginning or end may have been hard to resist. Sometimes the motivation may have been less nefarious. For a librarian or collector, anonymous works present an inconvenience, making them harder to shelve and retrieve, which again offers an inducement to insert a well-known author’s name, perhaps or perhaps not followed by a question mark and thus incidentally, increasing the value of the collection.

3.2 It was not until 1693 that in Mainz the first collection of Froberger’s works appeared in print, Bourgeat 1693, followed a few years later by a second collection, Bourgeat 1696, issued by the same publisher, Ludwig Bourgeat. The two Bourgeat collections seem to have been drawn largely on the same fund of works as Group B, and some works show almost identical variations from the corresponding Group A versions.[21] Moreover, two additional features reveal that their contents were not copied directly from the composer’s manuscripts.

3.3 The sixth of the eight toccatas in Bourgeat 1693, although included in Adler’s edition as Froberger’s Toccata XVII, does not form part of the Group B repertory and, in fact, is not by Froberger at all but rather by his younger colleague Johann Caspar Kerll. There can be no doubt that Bourgeat was mistaken in attributing this toccata to Froberger because its incipit is included as Toccata 7 in Kerll’s thematic catalog of 1686, described earlier.[22] Furthermore, some revealing differences from the autograph versions appear in a few passages in Fantasias II and IV.[23]

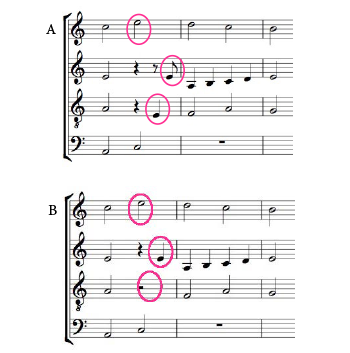

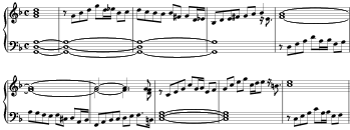

3.4 Examples 1a and 1b compare a brief passage from Fantasia II in the Libro Secondo and Bourgeat 1693. In the latter the “mi, fa, la, sol” subject in the tenor, in stretto with the soprano, has lost its “mi” opening. The reason for the revision may have been to avoid tripling a major third with the bass. Examples 2a and 2b compare a passage from Fantasia IV, “sopra sol, la, re.” Here the revision avoids doubling the “mi” in the outer voices, resulting in an ascending minor seventh in the bass. In Ex. 3 from the same Fantasia, a doubled major third is once again avoided, but this causes double trouble, because not only has the “re” of the “sol, la, re” subject been transformed to a “fa,” but the change also introduces parallel octaves between alto and tenor. There are a few more infelicities in the revised versions, but these examples should suffice.

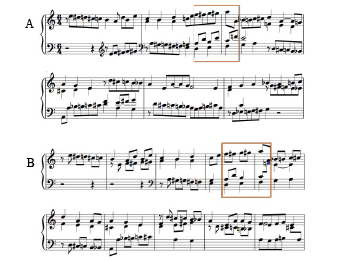

3.5 Could these alternate readings represent Froberger’s earlier drafts or later revisions of the Libro Secondo versions? It is hard to imagine a master of counterpoint like Froberger introducing mistakes like a melodic rising minor seventh and parallel octaves, even in a youthful first draft. There is, however, a simpler and more plausible explanation. Froberger notated the autograph versions in partitura or open score, whereas in the Bourgeat edition those fantasias are written in two-staff keyboard score. My guess is that someone––perhaps Bourgeat’s music editor––decided to transcribe these works from his partitura exemplar to a more user-friendly keyboard score. Rather than accidentally making copying errors, he introduced deliberate editorial “corrections,” such as eliminating doubled and tripled major thirds with the bass, even if those doublings apparently had not troubled the composer.

3.6 There is nothing shocking about such editorial interventions. They were made as a matter of course when copying music, because the transcriber, like the composer, did not regard what he had in front of him as a definitive text, not to be tampered with. But these misguided revisions, which will be referred to here as “the Mainz variants,” unambiguously point to a likely relationship among the versions in other sources that have the identical alternate readings.

3.7 We do not know what sources Bourgeat drew upon for his Froberger editions––sources that evidently included the misattributed Kerll toccata and the “corrected” versions of the two fantasias (unless, of course, it was Bourgeat’s music editor who invented those “corrections”).[24] In a sense it does not matter, since most likely the edition itself rather than its sources served as exemplar for all later sources incorporating these inauthentic elements. A printed score, of which ordinarily many identical copies are distributed, would doubtless serve as model for many more copyists than a single manuscript (the more so since the print medium tends to give an illusion of authority). When even today exemplars of the Bourgeat Froberger editions survive in at least a dozen libraries in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, England, France, Germany, and the U.S., it becomes highly probable that they served as the model for later sources containing the same inauthentic anomalies. Thus, the presence of the Mainz variants shows that at least part of the content of some important and much relied-upon Froberger sources likely derives from the not-entirely-trustworthy Bourgeat prints rather than from an independent tradition that goes back to the composer. It is telling that the Mainz variants do not appear in the open-score versions of Fantasias II and IV in the “Fughe e Capricci” manuscripts, which agree with the autograph Libro Secondo readings. This is why I proposed including the “Fughe e Capricci” manuscripts among the sources of Group B. I shall denote the manuscripts showing the Mainz variants, and hence presumed to have drawn on the Bourgeat editions, as source Group C. A further characteristic of the Group C sources is that, unlike those in Group B, they never include the biographical annotations or the avec discrétion performance instructions. This lack presumably reflects the prints, in which the annotations also are missing.

3.8 Two members of the C group are of special interest to my quest: the Edgeworth MS and the Muffat MS. Edgeworth is almost entirely in the hand of John Blow (1649–1708) and dates from his last years, ca. 1700 or thereafter. It contains South-German repertory but, except for a chaconne by Johann Caspar Fischer, contains no composer attributions, probably because Blow originally copied the manuscript for his own use. A sequence of twenty pieces corresponds to the entire content of Bourgeat 1693 (including the Kerll toccata) except for Toccata XXI. The eight toccatas appear in reverse order from those in the print; the four contrapuntal pieces (including the two fantasias with the Mainz variants) were copied in their original order starting from the back of the manuscript. In a 1960 article, Thurston Dart used the large number of Froberger pieces in this manuscript as evidence for an independent English Froberger tradition dating to the composer’s visit in 1662,[25] an idea picked up by a few other scholars.[26] However, evidence of dependence of those pieces on Bourgeat 1693 removes the basis for his argument.[27]

3.9 The first segment of the Muffat MS is in the hand of Gottlieb Muffat (1690–1770) and dates from ca. 1720 or earlier.[28] The only composer attribution in this segment appears above the first of the eleven numbered toccatas in the form “Del Sig:re Froberger,” but one presumes it was intended as a “blanket attribution,” covering Muffat’s entire autograph part.[29] The segment includes all of the contents of Bourgeat 1693 (again, with the Kerll toccata and the two fantasias with the Mainz variants) and the pieces from Bourgeat 1696 not present in the earlier print: nine toccatas (seven in precisely the same order as in Bourgeat 1693), eight contrapuntal pieces, and in addition, five pieces that are not found in either of the Bourgeat prints. These are Fantasia I, published in 1650 in Musurgia Universalis, Canzona I and Capriccio XIII, both known from other sources in the A and B groups, and two toccatas that are not found in any of the A or B sources. These two follow the nine numbered toccatas from Bourgeat 1693 and are designated in Muffat as Toccata Decima and Toccata Undecima. They are known to us, following Adler’s numbering, as Toccata XIX and Toccata XX. As outliers they deserve special scrutiny, which finally brings me to the question posed in the title of this article.

4. What the Sources of Toccatas XIX and XX Tell Us

4.1 I will concentrate here on Toccata XX but will occasionally touch upon the equally baffling source situation for Toccata XIX. All three editions of Froberger’s collected keyboard works, those by Adler, Schott, and Rampe (cited as a group in Appendix 1), include Toccata XX among the composer’s works. Rampe even lists it among the “Werke gesicherte Authentizität—Works of Certain Authenticity.”[30] For many years the piece has been welcomed without reservations in anthologies such as Karl Straube’s Alte Meister des Orgelspiels[31] and on complete works CD albums such as Bob van Asperen’s Froberger Edition.[32] So why ask who wrote it?

4.2 When investigating authorship, musicologists generally employ two tools: studying the sources and studying (or listening to) the music. Regarding Toccata XX’s sources, I’ve already mentioned its potentially problematic status as an outlier—it is not a member of either Group A or Group B.[33] As to the music, I have always felt a bit ambivalent about this work. Some of its formulaic traits don’t seem to accord with Froberger’s free spirit, although it does show a forward drive and turns of phrase characteristic of the composer. I will return later to these admittedly personal impressions, but now go on to look at what we can learn from the sources.

4.3 The critical report on this work in the Rampe edition lists three sources, all of which indeed name Froberger.[34] This would appear encouraging, even though the thematic catalog included in the final volume of the edition also lists a fourth source, which names another composer.[35] However, as is symptomatic of this gargantuan edition, half of the known sources are missing from the list. I provide here a summary of all the sources known at this time; see Table 1. Since most versions are not complete, I have indicated which segments are included (see the complete score in Appendix 3).[36]

4.4 Gresse MS. The Gresse MS, perhaps the earliest among these sources, reveals very little about Toccata XX. The manuscript does not provide any dates or names of scribes. Allan Curtis, editor of a partial modern edition, dates the portion containing the toccata excerpt to the 1680s or 1690s, in any case after 1677.[37] Most of its content is French in orientation, including some Lully adaptations; it includes no other works in any way related to Froberger. Only the opening portion of our toccata is provided and is given the title “Praeludium.” One feature of interest is a tag that has been added to its ending. Since the original excerpt concludes with a cadence in the dominant key of E minor (Ex. 4a), the copyist added a quick turnaround to get back to the home key of A minor (Ex. 4b). That same figure can also be found in Toccata XIII (Ex. 4c).This might be considered a small plus for Froberger’s authorship, since it suggests that the copyist had access to another Froberger toccata, or more likely, had it in his fingers.

4.5 Hereford MS. We don’t fare any better with the English Hereford MS.[38] It contains mostly organ parts for anthems and other service pieces, but among them are two works without title or attribution that appear to be intended for use as voluntaries. The first one corresponds to segment 1 of Toccata XX, the second one is the prelude to a suite by Purcell. The note values in the Froberger fragment are doubled and there are several other variants. Barry Cooper attributes this version to the hypothetical independent English Froberger tradition postulated by Thurston Dart,[39] but we saw in our earlier discussion of the Edgeworth MS that evidence for Dart’s proposed independent tradition is lacking.

4.6 Innsbruck MS. For Siegbert Rampe, the attribution to Froberger in the recently discovered Innsbruck MS was crucial to his authentication of Toccata XX because he believed it now provided, along with the Muffat MS, two independent sources of a Viennese transmission (“Wiener Überlieferung”), and in his view “all independent readings documented in at least two sources derive from the composer himself.”[40] Aside from the questionable rationale of this principle, which does not take the reliability of those sources into consideration, the Froberger concordances in Innsbruck appear not to be independent of those in Muffat. The Innsbruck MS, a large anthology of organ music, is believed to have been compiled by Elias de Silva (ca. 1665–1732) after ca. 1702 for use in church services.[41] It contains works by both Frescobaldi and Froberger among other notable masters, but it is an unreliable source with respect to both its attributions and its musical texts. For instance, in this manuscript, Froberger’s Capriccio V is attributed to Frescobaldi, and several other Frescobaldi attributions are also highly implausible. Most relevant here: like the Muffat MS, it includes Froberger’s Fantasia IV with the Mainz variant, indicating a dependency, whether direct or indirect, on Bourgeat 1693.[42] Hence, the Innsbruck MS belongs to source Group C rather than Group B. It seems likely that some of the sources used by its copyist for Toccata XX (as well as for Toccata XIX, which appears anonymously––see below) and Fantasia IV are related to those used by Muffat. In other words, the Innsbruck MS does not provide solid independent confirmation of the Froberger attribution of Toccata XX.

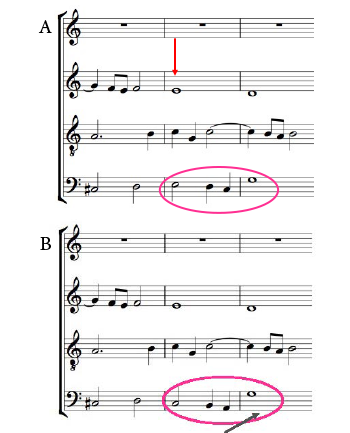

4.7 The Lady’s Entertainment and A Second Collection. The appearances of segments 1 and 2 of Toccata XX in two British publications, The Lady’s Entertainment, or Banquet of Musick from 1708, and A Second Collection of Toccatas …, from 1719, contribute little to clarify its authorship. The Lady’s Entertainment was originally published in twelve monthly installments as Mercurius Musicus: or A Monthly Entertainment of Musick beginning in November 1707.[43] Each installment commenced with an instrumental piece, which served to introduce a group of songs and often matched the key of the first song. The third installment, presumably appearing in January 1708, opens with a “Toccata del Sigr. Simonelli,” followed by a keyboard setting of an anonymous song, “In vain is Complaining,” both in A minor. Two of the other installments open with toccatas attributed to Italians (Amadori and Fontana). The toccata attributed to Simonelli corresponds, however, to Segments 1 and 2 of Toccata XX; see Ex. 5a.

4.8 These segments reappear in a 1719 publication, A Second Collection of Toccatas, Vollentaries and Fugues, which reprints parts of several earlier publications, including a sequence of seven toccatas. Aside from Toccata XX, two other pieces were taken from The Lady’s Entertainment, all printed from the same plates except for some alterations in the captions. The alterations generally consisted of changing “Toccata” to “Toccato [sic] or Vollentarys,” but, as can be clearly seen by comparing Examples 5a and 5b, the name “Simonelli” following “del Sigr.” was replaced by “Frobergue XV.” Was the name changed because the publisher John Walsh thought that in England the name Froberger would have more sales appeal than Simonelli, or had someone informed him that the attribution to Simonelli was mistaken? And who exactly was Signor Simonelli?

4.9 In the critical notes to his edition, Rampe states that in The Lady’s Entertainment the toccata is attributed to “Carlo Ferdinando Simonelli (ca. 1617–1653),” a colleague of Froberger’s at the Vienna Court Chapel, although the name Carlo Ferdinando does not appear anywhere in that edition.[44] Rampe goes on to suggest that perhaps “Froberger turned to a toccata by his colleague Simonelli for the unusual opening section and proceeded from there on his own,” notwithstanding his acceptance of the entire toccata among Froberger’s “Works of Certain Authenticity.”[45] A few years later Rampe published that same opening section of Toccata XX (segments 1 and 2) by itself as a Toccata by Carlo Ferdinando Simonelli![46]

4.10 But did the attribution to Signor Simonelli, correct or not, refer in fact to that Carlo Ferdinando, a mid-seventeenth-century member of the imperial court chapel in Vienna? When in a 1982 article I first drew attention to the conflicting attributions in the two London publications, I proposed a more likely candidate, the Roman organist Giacomo Simonelli, active from at least 1660.[47] I favored the later Giacomo over Carlo Ferdinando because he was one of a group of organists and composers active in Rome during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries whose works had made their way into several English manuscripts and publications, including our two London prints.[48] One of those manuscripts, the Woodcock MS, dated 1701, contains another toccata attributed to Simonelli.[49] Like Toccata XX, it commences with a phrase that is echoed almost literally at different pitch levels, a feature not rare in that Roman repertory but virtually never encountered in Froberger’s authenticated works; see Ex. 6.

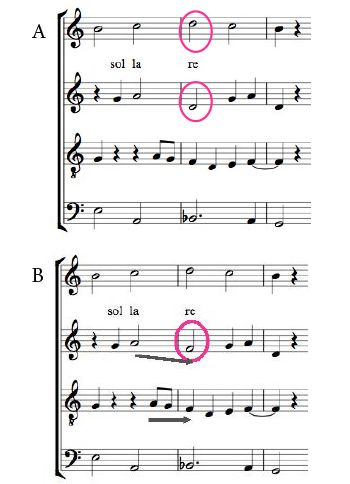

4.11 Minoriten 719 and Minoriten 721. Two recent discoveries have added to this already confusing situation. Among the extensive musical holdings of the library of the Minoritenkonvent in Vienna is the six-volume early-eighteenth-century verset collection of Alexander Giessel (1694–1766).[50] Many of these brief versets were adapted from works of earlier composers, sometimes identified correctly or, just as often, mistakenly. The versets are organized by key, and the third volume, entitled “Varia Præludia, Toccatæ, Fugæ, et Versiculi, ex E♮ dur et E mol” (various Preludes, Toccatas, Fugues, and Versets in E major and E minor), includes a verset with the inscription “fuga inversa in E mol Dni Alberizi, a Dno Lebhard mihi communicata” (fugue in contrary motion in E minor [by] Domino Alberizi [Vincenzo Albrici], transmitted to me by Domini [Adalbert] Lebhart). This turns out to be the chromatic section 3 of Toccata XX (mm. 48–56); see Ex. 7.[51] There are a few small differences; for example, the rather odd course of the tenor in mm. 49–50 in the Muffat and Innsbruck versions (the only other appearances of this segment) has been modified (mm. 4–5), resulting in parallel fifths between tenor and bass (see further discussion of this variant below). Some of the differences, such as the omitted ties, are fairly typical for this scribe, and may be a sign of haste or inexperience. On the same page, underneath this fragment, has been entered a “Fuga Dni Alberizi bona in C dur,” which proves to be a hitherto unreported segment (mm. 63–78) from Froberger’s Capriccio XVIII.[52]

4.12 This is not the only excerpt from Toccata XX in Giessel’s verset collection. In the fifth volume (“Varia Præludia, Toccatæ, Fugæ, et Versiculi, ex G♮ dur et G♭ mol”) we encounter the ubiquitous opening section (mm. 1–16), but transposed a step down, with a single flat signature; see Ex. 8.[53] Again the attribution is to Albrici: “Toccatina sicuti fuga Dni Alberizi,” which could be loosely translated as “Little toccata in the manner of a fugue by Mr. Alberizi.” Aside from the transposition and the truncation after sixteen measures—both the consequence of the utilitarian intent to add it to a collection of versets organized by key—close comparison suggests that this was a careful copy, but not clearly derivative of any one of the other surviving versions.

4.13 Vincenzo Albrici (1631–87) was in his day probably a better-known musical figure on the European scene than Froberger. He traveled even more widely, having held important posts at courts and in churches in Rome, Stockholm, Stuttgart, Dresden, possibly Paris, Leipzig, and Prague, and, of special interest here, he spent 1662 to 1668 in England at the court of Charles II.[54] Although his musical output was considerable and important (most of it unfortunately now lost), he is not known for a legacy of keyboard music, notwithstanding several organ appointments. Incidentally, while the appearance of fragments from Toccata XX and Capriccio XVIII together on the same page, both attributed here to Albrici, would seem to argue for Froberger’s authorship of the toccata, the credentials of that Capriccio are not impeccable either. The work is not transmitted by any of the A or B sources except for its inclusion in the late eighteenth-century “Fughe e Capricci” manuscripts. Besides, like many musicological arguments, the argument based on the appearance of the two Albrici attributions one above the other on the same page could be turned around: someone who knew the toccata to be the work of Albrici might assume that a piece immediately following it in the source was also his work. Although attributions in the Giessel collections hardly form an ironclad guarantee, a connection of Albrici with Toccata XX is an intriguing possibility.

4.14 Muffat MS. We already noted that Gottlieb Muffat copied out the entire contents of Bourgeat 1693, and that following the nine toccatas, he added Toccatas XIX and XX as Toccata Decima and Toccata Undecima. It may have been his plan to create a volume of the complete keyboard works of his illustrious predecessor at the Vienna court chapel, and it seems that after finishing copying the pieces from the Bourgeat prints, he supplemented them with nine works from other sources accessible to him. We don’t have any idea, however, where he obtained the two outlier toccatas, but probably not from the flawed Innsbruck MS. Even though that manuscript is the only other known source for all four segments of Toccata XX (with minor divergences), it contains a version of Toccata XIX that is entirely different and lacks an attribution to Froberger.

4.15 This takes us to the sources for Toccata XIX, which present their own mysteries––see Table 2.

4.16 Brasov Tablature. The earliest source, the Brasov Tablature, presents only the final segment of Toccata XIX, which is attributed to “Geor. Frob.”[55] Froberger did have a brother named Johann Georg,[56] who was a member of the Württemberg court chapel but not known for writing keyboard music, so the “Geor.” was probably a mistake.

4.17 Cambridge 652. Cambridge 652 is the only other source containing the same three segments found in Muffat’s version of Toccata XIX, but with an attribution to Bernardo Pasquini, a central figure among that group of Roman musicians whose keyboard works are frequently encountered in English sources.[57] Curiously, it is followed in the manuscript by a “Fuga: Froberg.,” which corresponds to the first part of a “Capriccio Di Sigr G. Froberger” that precedes Toccata XX in the Innsbruck MS.[58]

4.18 Innsbruck MS. The opening segment of Toccata XIX also makes an appearance in the Innsbruck MS, but without attribution. The two canzona-like segments that follow it in the Muffat MS, have been replaced by Froberger’s Fantasia II.[59] Although Innsbruck also contains Toccata XX, the two works do not appear in the same part of the manuscript.

4.19 Muffat MS. The Muffat MS the only source that includes complete versions of both Toccata XIX and Toccata XX as works of Froberger and in which they appear together. Several parallels in the source situations of these two works raise the question whether they are in some way related or have a common origin. In addition to their adjacent placement in Muffat, both are transmitted by Innsbruck, and both appear in (different) English sources from around ca. 1700 with attributions to Italians active during that time. Another kind of parallel could be seen in the way both begin with a phrase with a wide ambitus and accompanied by a sustained harmony, which is followed by an imitation of the phrase by the bass voice in the dominant key, accompanied by a sustained chord in the treble. However, while we remain in the dark about the origin of either work, exploring a possible relationship between them does not seem helpful.

4.20 In summary, Toccata XIX is present, at least in part, in four sources from central Europe and England, dating to several decades after Froberger’s death, two with attributions to him, one attributed to Bernardo Pasquini, and one without attribution. Toccata XX appears, at least in part, in eight sources from central Europe, the Netherlands, and England, with three attributions to Froberger, two to Albrici, one to Simonelli, and two without attribution. How to decide on the real author of either work? Looking simply at the numbers would make Froberger the winner, but that consideration clearly is too simplistic: it fails to consider either the credibility of the sources or their mutual dependence. Another principle sometimes invoked is that in a conflict of attributions between a famous and a relatively obscure composer, the obscure name is more likely to be the correct one. The reasoning is that in cases of doubt (or deliberate fraud) someone is more likely to attach a famous name than an obscure one to a composition or to change the latter into the former. But this principle also glosses over the complex aspects of these sources and their relationships. Besides, to the copyist of the versets in the Giessel collection, Froberger may not have been a more famous name than Albrici, and to Renate Harris, he may not have been more of a celebrity than Bernardo Pasquini. If such considerations are a dead end, should we look instead for answers in the music itself?

5. Does the Music Provide the Answers?

5.1 Sensitive musicians frequently feel in their hearts that some piece of music has to be by a certain composer––usually a composer they love. Often those hunches turn out to be correct, but there certainly are cases where they prove to be wrong. The obvious problem with using intuition as the basis for decision is its subjective nature. To support our hunch regarding the authorship of a composition, we may produce elaborate arguments and construct ingenious theories, although there is always the danger that our reasoning will be colored by the desire for our hunch to be true. It is always a good idea to test our theories by trying to make a case that they are not true and to see how that affects our belief in them. I shall try to do this regarding the question of who wrote Toccata XX.

5.2 A common method for determining whether a given piece is by composer X rather than composer Y is to look for features that frequently appear in the other works of X but rarely or never in the works of Y. This method is often resorted to, even when virtually no works are known by composer Y (as is the case with respect to keyboard music for Albrici or Simonelli). I can best illustrate the hazards of this method with arguments both pro and contra Froberger’s authorship of Toccata XX. Bob van Asperen, in the extensive and insightful notes to his recording of Froberger’s keyboard works,[60] made an eloquent and impassioned plea for the pro Froberger case. Some of his arguments appear persuasive, others perhaps less so, especially when they are based on conjectures that themselves are unverifiable. For example, comparisons with the “Chigi toccatas” hardly provides strong support for Froberger’s authorship, since their connection with Froberger is, if anything, more questionable than that of Toccata XX.[61] Similarly, features in Toccata XX that seem atypical for Froberger are explained by hypothesizing that the work was the product of the composer’s early years, but we know absolutely nothing about what kind of music he wrote in those years.[62] Even striking resemblances to undisputed Froberger compositions do not necessarily settle the case. Asperen notes that a short thematic motive used in a point of imitation in segment 4 of Toccata XX (mm. 71–78) also appears in the Allemande of Suite XIII (mm. 2–10). If this resemblance is not merely coincidental, it might just as well be that the toccata was written “à l’imitation de Mr Froberger” by a colleague or admirer for whom the reference to a work of the master had some special significance.

5.3 Those who wish to make a case contra Froberger’s authorship of Toccata XX, could point to the lengthy opening phrase of even eighth notes relieved only by an occasional pair of sixteenths, which is repeated four times in transposition over calm, sustained harmonies. This is certainly unlike the beginning of any other Froberger toccata. His compositions in that genre, like those of his teacher Frescobaldi and of other early Italians, generally commence with highly variegated rhythmic figures, unexpected dissonances, explosive scale runs, and startling harmonic progressions. The formulaic character of this toccata’s opening, and, for that matter, a similar lack of rhythmic differentiation in some other sections, don’t seem to accord with Froberger’s capricious spirit. As was noted in our earlier discussion of the Simonelli attribution, a similar opening ploy and extended passages of even note values are frequently encountered in toccatas by other organists of the turn-of-the-century Roman circle. Incidentally, the noted features of the toccata’s opening section may well be why several organists selected this section for use as a verset (e.g., its inclusion in Minoriten 721 and also probably in Gresse). It is easy to listen to and certainly easier to play than the beginnings of many Froberger toccatas.

5.4 If it seems that I have tried to plant seeds of doubt about the authorship of Froberger’s Toccata XX, it is not because I consider it to be a bad piece. On the contrary, as I stated at the beginning of this article, it is an exciting work, undoubtedly superior to many seventeenth-century toccatas. However, my intuition does not tell me that from the beginning to the end Toccata XX must be by Froberger. Yes, it contains several recognizable Frobergian features, but that is also true of much later seventeenth-century keyboard repertory––his impact was pervasive.

5.5 The point is that scholars are not likely to agree about “answers from the music,” unless supported by evidence from the sources. There was once a hope that we might find answers to authorship questions by feeding scores into a computer and developing an algorithm that would produce statistical measures of the likely authors. I am skeptical that this hope can be realized for seventeenth-century keyboard music because we lack enough appropriate data for such a “big data” approach. I mentioned previously the lack of music from Froberger’s early years and the entire, or almost entire, absence of surviving keyboard music by Albrici or Simonelli (whether Carlo or Giovanni). Even trying to use such a method for determining whether a work such as Toccata XIX derived from Froberger or from Bernardo Pasquini, each of whom did leave us a mass of toccatas, would be problematic, because both were brilliant composers but never quite predictable. Either one might have started a toccata in a manner different from any of his others.

5.6 Should we continue to credit a work, without reservation, to a specific composer when convincing, source-based evidence is lacking? After all, we would not wish to mislead the public any more than medical researchers want to make unsubstantiated claims about the effectiveness of a vaccine. Toccata XX may indeed be a youthful effort Froberger failed to suppress or something he jotted down for a friend or patron during one of his travels, but it may just a likely be an attempt by one of his students or admirers to imitate his manner, or even be a deliberate forgery. Besides, unless new evidence comes to light to the contrary, we cannot entirely rule out an Albrici, a Pasquini, or a Simonelli as its composer. All this has no bearing on whether we can keep playing or enjoying this toccata. But let’s start calling Toccata XX, depending on our hunches about the piece, either “possibly by Froberger,” or “probably not by Froberger,” or, keeping all options open, “from the school of Froberger.”

Acknowledgments

I wish to express my deep gratitude to David Schulenberg for the invaluable comments he made on a draft of this article and for his several helpful suggestions, almost all of which I took to heart.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Short titles of editions

Appendix 2: Short titles of sources

Appendix 3: Score of Toccata XX (adapted from Muffat MS)

Examples

Ex. 1. Fantasia II, mm. 10–11: a. Libro Secondo; b. Bourgeat 1693

Ex. 2. Fantasia IV sopra sol, la, re, mm. 3–4: a. Libro Secondo; b. Bourgeat 1693

Ex. 3. Fantasia IV sopra sol, la, re, mm. 7–8: a. Libro Secondo; b. Bourgeat 1693

Ex. 4. Hypothetical patch from Toccata XIII in Gresse MS: a. Toccata XX (adapted from Muffat MS), mm. 15–17; b. Praeludium (adapted from Gresse MS), mm. 15–18; c. Toccata XIII (adapted from Bourgeat 1693), mm. 7–9

Ex. 5. Toccata XX, mm. 1–6: a. Ladies Entertainment; b. Second Collection

Ex. 6. Simonelli, Toccata in A terza minore in Woodcock MS, mm. 1–9

Ex. 7. Toccata XX, beginning of Segment 3: a. Muffat MS, mm. 48–53; b. Minoriten 719, mm. 1–10

Ex. 8. Toccata XX in Minoriten 721, mm. 1–10

Tables

Table 1. Sources for Froberger, Toccata XX

Table 2. Sources for Froberger, Toccata XIX