The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2024 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 27 (2021) No. 2

Venetian Opera Texts in Naples from 1650 to 1653: Poppea in Context

Valeria Conti and Nicola Usula*

Abstract

L’incoronazione di Poppea (text by Busenello, music attributed to Monteverdi) was one of seven Venetian operas staged in Naples, 1650–1653, by the touring companies Discordati and Febiarmonici under the patronage of the viceroy Íñigo Vélez de Guevara. The others were Didone; L’Egisto; Giasone; La finta pazza; Veremonda, l’amazzone di Aragona; and Rosinda, retitled Le magie amorose. Librettos and scores for these operas produced in Naples show textual modifications that occurred after the Venetian premieres, but they also show readings that apparently antedate the extant Venetian sources, reflecting a complex process of kaleidoscopic contamination.

PART ONE: Venetian Operas in Naples, 1650–1653

PART TWO: Textual and Dramatic Features in the Neapolitan Sources

5. References to the Neapolitan Context

6. Reference to the Performances

7. Censorship in the Neapolitan Librettos

PART THREE: Reliability and Origins: The Text in the Neapolitan Sources for Poppea

10. A Score as a Principal Antigraph

12. Hybridization toward an Enhanced Text

PART FOUR: Authorial Issues and Performative Traces in the Neapolitan Sources for the Other Operas

13. Venetian and Neapolitan Authors

14. Neapolitan Librettos and Venetian Scores

15. The Touring Companies’ Manipulations

16. Conclusions: Methodological and Historiographic Results

1. Introduction

1.1 The contradictory characteristics of the Neapolitan sources for L’incoronazione di Poppea by Giovanni Francesco Busenello, with music mostly attributed to Claudio Monteverdi, raise a number of doubts concerning their reliability and textual congruity with their Venetian origins. Since the early-twentieth-century discovery of the score in Naples, the structural and stylistic features of the Neapolitan score and libretto have stimulated some strong skepticism among scholars. Only a few have dedicated their attention to the libretto’s evolutionary path from the 1643 Venetian premiere to the 1651 Neapolitan performance, while elements arising from a comparison between the Neapolitan sources and all those that still survive today have never been considered alongside the extant sources for the other operas that were revived in Naples after their Venetian premieres. Poppea actually shares the same production framework and very similar adaptation strategies with at least six other Venetian works staged in Naples between 1650 and 1653: La Didone in 1650; L’Egisto and Il Giasone in 1651; La finta pazza and Veremonda, l’amazzone di Aragona in 1652; and finally La Rosinda, retitled Le magie amorose, in 1653. Revived by the touring companies known as the Discordati and the Febiarmonici under the patronage of the viceroy Íñigo Vélez de Guevara, these operas share many common elements that can help us understand the nature of the Neapolitan sources for Poppea.

1.2 First, the relationship between the city and all of the Neapolitan sources turns out to be very strong: we find references to the political and cultural milieu in dedications, paratexts, and poetic texts. Furthermore, the texts copied or printed in Naples show the results not only of manipulations that occurred specifically for the Neapolitan revivals, but also the changes that followed the premieres early on, in order to make the operas more suitable for courts and cities far from Venice. However, the most surprising result of this study is the closeness of the texts in the Neapolitan sources to their Venetian roots: the touring companies in charge of performing in Naples, in fact, acted as a direct link between Venice and the Neapolitan stage. Therefore, the librettos and scores printed and copied in Naples present textual materials far closer to the Venetian background than expected, and this feature rehabilitates their status in terms of closeness to their original authors’ intentions and, consequently, in terms of reliability. Nonetheless, we also note that the scribes and publishers of these sources sometimes aspired to make as “complete” a work as possible, mixing different readings of the operas in order to create what they perceived to be the best possible text. Hence, especially in the case of Poppea, the final result is a patchwork made up of pieces of textual fabric with different origins.

1.3 This study is structured in four main sections: we present the seven works and their performative context in the opening section (Part One), followed by an examination of the features found only in the Neapolitan sources (Part Two). In the succeeding sections, we provide insights into the textual status and the manipulative processes we trace in the Neapolitan sources: first with a focus on Poppea (Part Three), and then taking into consideration the other six operas (Part Four). Three appendices present (1) the list of the extant sources for all seven operas; (2) the transcription and English translation of paratexts and poetic materials added in the Neapolitan librettos; and (3) the list of vocal pieces for Poppea for which the music is present only in the Neapolitan score.

PART ONE: Venetian Operas in Naples, 1650–1653

2. Neapolitan Librettos

2.1 The introduction of opera alla veneziana to Naples is linked to the viceroy Íñigo Vélez de Guevara, 8th Count of Oñate and Villamediana, a Spanish ambassador in Rome who had been dispatched to Naples in March 1648 to help put down the rebellion against the Spanish government led by Masaniello.[1] In a very short time, the rebellion was stifled and Oñate restored Spanish hegemony in the viceregal city, in the process enacting a violent suppression of the rebels.[2] During the following years he promoted public spectacles with music, in order to celebrate the efficacy of his politics and the power of the Spanish monarchy. In 1650, therefore, in the midst of a renewed social serenity, Oñate welcomed the arrival of a touring company of musicians that introduced operas “a l’uso di Venetia” in Naples.[3] This company, called Accademici Discordati, was led by the Cremonese architect and operatic set designer Curzio Manara; it staged at least three Venetian operas in Naples in 1650 and 1651: La Didone, L’Egisto, and L’incoronazione di Poppea.[4]

2.2 The first opera imported from Venice by the Discordati was Didone by Giovan Francesco Busenello and Francesco Cavalli, which had premiered at the Teatro S. Cassiano in 1641 and was revived in Naples from September to November 1650.[5] The only extant source for the Neapolitan performance of Didone is a printed libretto with no indication of city or publisher, whose dedication letter Manara signed in “Napoli li 10. Ottobre 1650.” The leader of the Discordati dedicated this print to Marquis Don Antonio de Tassis (vice-captain of the Neapolitan royal guards and relative of Count Oñate), referring to the eagles in the de Tassis family emblem as a symbol of protection for the abandoned queen Didone, and for the performance as well.[6] The success of this new sort of spectacle must have been outstanding, and, in order to accommodate more spectators and a more splendid scenography, in November Oñate ordered the construction of a new theatrical hall in the viceregal palace, larger than the “stanza del Pallonetto” used until then.[7] From then on, opera in musica became the main entertainment in the palace, addressed to a broad audience, from the nobility to the lower classes, which had access to the performances via both invitations and tickets.[8] After Didone, the sources provide information about two other operas performed during the Carnival season, between the end of December 1650 and February 1651. Two extant librettos printed in 1651 in Naples document the staging of two works that had premiered in Venice in 1643: the first was Egisto by Giovanni Faustini and Francesco Cavalli (premiered in Teatro S. Cassiano), and the second L’incoronazione di Poppea (Teatro SS. Giovanni e Paolo).[9] The only extant copy of the Neapolitan Egisto, printed in Naples by Egidio Longo, bears the indication “In Venezia et in Napoli MDCLI.”[10] The place of publication and the name of the publisher are the only elements that permit us to assign this libretto to Naples, since, unlike the other Neapolitan sources, it is the only one without any dedication on the title page or any letter to the dedicatee.[11] In contrast, the Poppea libretto clearly announces its dedication on the title page, where we read the famous alternative title of the opera and its important dedicatee, no less than the viceroy himself: “Il Nerone overo L’incoronatione di Poppea, … dedicato all’illustrissimo et eccellentissimo signor Don Inigo De Guevara, et Tassis …” In the dedication letter, Manara, underlining the connection between the opera and Count Oñate, wrote that the character Ottavia went from Venice to kneel before Naples (“gran reina Partenope”) and to ask the viceroy to intercede for her, due to his recently proven ability to re-establish kingdoms (“risorger corone”).[12]

2.3 From the end of 1651 onward, another company of musicians, called the Febiarmonici and linked in some way to the Discordati, was responsible for the operatic performances in Naples, and before 1654 they revived at least four other Venetian operas: Il Giasone; La finta pazza; Veremonda, l’amazzone di Aragona; and La Rosinda (under the new title Le magie amorose). On 12 July 1651 the Spanish queen Marianne of Austria gave birth to her first child by King Philip IV: the Infanta Margarita Teresa. The Neapolitan viceroy had been planning a celebration for months, and on 6 September, in the royal palace, the Febiarmonici staged Giasone by Giacinto Andrea Cicognini and Francesco Cavalli (premiered in Venice, Teatro S. Cassiano, 1649).[13] On 2 September 1651 the Neapolitan publisher Roberto Mollo had signed the dedication of the libretto printed for the occasion, since Manara was very likely no longer involved in the operatic scene.[14] In this case, the dedicatee was the viceroy’s daughter, Catalina de Guevara y Tassis, vice-queen of Sardinia. However, the publisher did nothing to hide the work’s real dedicatee. Indeed, Mollo kept continuously referring to her “glorioso padre” (glorious father), calling him the “vero liberatore della nostra Italia” (real savior of our Italy), and specifying that, by that time, Count Oñate had already heard Giasone (which indicates it was performed before 2 September).[15] Between the end of June and the first days of July 1652, the Febiarmonici, guided by the famous dancer and scenographer Giovan Battista Balbi, performed in the “stanza del Pallonetto” one of their greatest successes: Finta pazza by Giulio Strozzi and Francesco Sacrati (premiered in Venice, Teatro Novissimo, 1641).[16] The main source for the Neapolitan performance of this important opera is a libretto printed by Roberto Mollo in 1652, and dedicated by the Feboarmonico singer Giovanni Paolo Bonelli to Michele Pignatelli, leader of the viceregal army against the French troops during the rebellion of Masaniello.[17] On 16 July 1652, another performance of Giasone took place in the palace;[18] however, a new grand occasion would soon arrive, allowing viceroy Oñate to show off the magnificence of Neapolitan theatrical performances. The avvisi of 10 December 1652 report the preparation of the scenography for new feste to celebrate the victory at the end of the Siege of Barcelona (11 October 1652) in the context of the Catalan Revolt (July 1651–October 1652). On 23 December, in conjunction with the birthday of the Spanish queen (22 December), the Febiarmonici, led by Giovan Battista Balbi, performed Veremonda, l’amazzone di Aragona by Giulio Strozzi and Francesco Cavalli, based on G. A. Cicognini’s Il Celio (premiered in Florence in 1646 with music by Niccolò Sapiti and Baccio Baglioni).[19] The Neapolitan source for this opera is a libretto printed by Roberto Mollo in 1652 and explicitly dedicated to the viceroy. Balbi signed the initial dedication to Count Oñate, and, among the usual requests for protection, he clearly highlights Veremonda’s attitude toward massacres (“straggi”), referring obliquely to the policy of repression carried out by the Spanish government in Naples.[20] Veremonda perfectly matched Oñate’s program of self-promotion through musical theater, even if the work had probably not been conceived for the Neapolitan court, and certainly not with the subjugation of Barcelona in mind: Giulio Strozzi, the playwright, died on 31 March 1652, i.e., more than six months before the fall of Barcelona.[21] An edition of the libretto for Veremonda printed in Venice and dated 1652 (with a dedication signed by Balbi on 28 January 1652) suggests that the opera could have premiered in Venice, under Balbi’s supervision, before being revived in Naples with some changes.[22]

2.4 The 1653 Carnival was extraordinary, and during that year, a large number of dramatic works with music were performed in the city; however, apart from another performance of Giasone on 8 October 1653, only one of them had Venetian origins.[23] It was Le magie amorose, the very first heavy reworking of a Venetian opera for Naples, based on Rosinda by Giovanni Faustini and Francesco Cavalli (premiere in Venice, Teatro S. Apollinare, 1651).[24] Balbi prepared this revival in Naples with the collaboration of the local poet Giulio Cesare Sorrentino, and once more he dedicated the libretto printed by Mollo to the viceroy.[25] The importance of this work, which we used as a chronological limit for our study, concerns a noticeable shift in the programming of operatic productions in Naples. From 1653 on, local compositions began to alternate with successful operas imported from Venice, usually arranged by local poets and composers. In 1653 at least four local works were staged in Naples: L’Arianna by Giuseppe Di Palma from Nola, La gara degl’Elementi by unknown authors, La vittoria fuggitiva by Giuseppe Castaldo and Francesco Marinelli, and probably Il Ciro by Giulio Cesare Sorrentino and possibly Francesco Provenzale.[26] After a new performance of Giasone (which was supervised by Balbi in October), the political situation changed drastically in November 1653, when García de Avellaneda y Haro, Count Castrillo, replaced Oñate as viceroy. The decision came from Madrid following protests against the excessive authoritarianism that Oñate demonstrated during the Restoration, and on 9 November one last unidentified “commedia” was performed in the palace, before he left the city on 20 November.[27] The change in political leadership did not interrupt musical life at the court, but during the following year an important transformation of opera in Naples took place. The Febiarmonici, dismissed from the court, assembled an autonomous company of musicians, and in 1655 gave birth to the Accademia dei Febi Armonici.[28] Furthermore, they began to stage operas at the Teatro San Bartolomeo, which had housed commedie since 1621 but was damaged in 1647, during the Masaniello revolution, and was finally restored in 1652 by Oñate.[29] Therefore, in 1654, they inaugurated a new era with the performance of at least two operas of Venetian origin: L’Orontea regina d’Egitto and L’amori d’Alessandro Magno e di Rossane, both premiered in Venice (in 1649 and 1651 respectively), with text by Giacinto Andrea Cicognini and music by Francesco Lucio.[30]

3. Neapolitan Scores

3.1 In addition to the seven librettos we have just introduced, two musical scores complete the trove of Neapolitan operatic sources for the years 1650–1653: the manuscripts containing Poppea and Giasone. Both are in the library of the Conservatorio “San Pietro a Majella” and seem to be linked to the Neapolitan performances in the early 1650s. They do not contain any dates or the names of authors, owners, or copyists, but while their provenance is still uncertain, some graphic and textual features suggest their common Neapolitan origins.

3.2 The score of Poppea was discovered only in the twentieth century, around 1925–1930, by Guido Gasperini, then librarian of the Conservatorio. It is in oblong format and is particularly refined from an aesthetic point of view.[31] The score of Giasone is also in oblong format, but its scribe copied across the adjacent verso and recto, in a layout usually called a libro aperto.[32] Unlike Poppea, however, the Giasone manuscript was known as early as 1810, when it appeared in a catalog of music from the Conservatorio della Pietà dei Turchini, whose collection was merged with the library of the Conservatorio S. Pietro a Majella in 1826. This manuscript seems to be the oldest of the three complete scores for that opera held in Naples.[33]

3.3 The two scores share the same watermark (the monogram “IHS” surmounted by a Greek cross and inscribed in an oval), revealing a Roman paper that was widespread throughout the viceregal territory during the seventeenth century.[34] Furthermore, although two different scribes were involved, each copying one of the two scores, their handwriting shares some similar graphical features, revealing that they most likely belonged to the same workshop, and that the manuscripts were possibly copied during the same period (probably around the 1651 performances of the two operas).[35]

3.4 Some elements that the scores share with the related Neapolitan librettos corroborate the link to the 1651 Neapolitan performances of the two operas. However, the two cases present some distinct peculiarities. As Alessandra Chiarelli and Ellen Rosand have already shown, the Neapolitan score and libretto for Poppea present some features that undoubtedly demonstrate their proximity.[36] In comparison with all the other sources, they share some line repetitions and redistributions, some merged scenes, as well as reattributions of lines to different characters, together with small but meaningful common textual variants.[37] Their main conjunctive element is Act 2, scene 7, a long solo lamento for Ottavia (42 lines), which in the two Neapolitan sources completely replaces a love scene for Nerone and Poppea.[38]

3.5 The relationship between the score of Giasone and the libretto printed in Naples in 1651 is slightly weaker, since their two texts do not have many exclusive correspondences. Their only important conjunctive variant is the displacement of the solo scene for the queen Isifile (Act 1, scene 14) to follow the final scene of the act, Medea’s incantation (Act 1, scene 15). This inversion of the two scenes is not documented before 1651, and therefore likely occurred contemporaneously in the Neapolitan libretto and score.[39]

PART TWO: Textual and Dramatic Features in the Neapolitan Sources

4. Premise

4.1 After identifying the group of seven printed librettos and two manuscript scores related to the Neapolitan performances, comparing them with all other extant sources for each opera reveals a number of elements specific to the Neapolitan sources. Since it is clear that the two companies of Discordati and Febiarmonici shared the same manipulative strategies, in this section we will discuss the textual and dramatic features of the Neapolitan sources as a group. However, not all of the elements unique to these sources originated in Naples. These librettos and scores, in fact, show not only manipulations made for the revivals in Naples, but also changes that might have been inherited from earlier sources, now lost.

4.2 These elements fall into three main categories. The first (Chapter 5) includes additions and replacements related to the Neapolitan sociopolitical environment. The second (Chapter 6) presents modifications related to the performances and the cast that, although appearing for the first time in the Neapolitan librettos, could have occurred before the performances in Naples. Finally, the third category (Chapter 7) deals with textual changes linked to censorship, which in some cases undoubtedly occurred in Naples, while in others could have been introduced before the Neapolitan revivals.

4.3 Indeed, there are cases in which, due to their peculiar nature and textual origins, some operas display manipulations that are similar to the Neapolitan ones, even though they undoubtedly occurred before the revivals in Naples. For example, the librettos for Egisto, Giasone, and Finta pazza do not present any uniquely Neapolitan interventions related to censorship, simply because they derive from versions of the texts that had already been modified by the touring companies for earlier revivals outside of Venice. On the other hand, in the case of Rosinda we know that, coming so soon after its Venetian premiere in 1651, its only revival was in Naples; therefore, the text required deeper interventions to fit the court’s tastes. The same could be said for Veremonda, although it is still uncertain whether it was first performed in Venice: comparison between the sources confirms that the Neapolitan libretto’s textual status succeeded the Venetian one and derived from an early Venetian version of the drama, modified in Naples to fit the context. Finally, the revivals of Didone and Poppea represent yet another case. Their Neapolitan sources, in fact, show the results of manipulations that might have occurred either in Naples or for some earlier performance. So far as we know, Didone could have been revived during the nine years between its 1641 premiere and its Neapolitan revival in 1650. Hence, its Neapolitan libretto could show elements that did not originate in Naples. Similarly, the new features we detect in the Neapolitan sources for Poppea could reflect both new and inherited adjustments. Indeed, after the 1643 premiere, this opera could have been revived many times before the 1651 Neapolitan performances, with the Discordati referring to sources with texts already manipulated for earlier court performances, such as the Parisian one, which appears to have been at least planned (although probably not by Manara) in 1647.[40]

5. References to the Neapolitan Context

5.1 The most evident manipulations in the Neapolitan sources are undoubtedly the additions that reflect the sociopolitical context. As already mentioned, dedicatee and performers are on full display in the printed librettos, both in the paratexts and in the poetic texts. The patrons had to be easily recognizable; therefore, together with the dedication letters, we can also find elements related to the contemporary political context in the poetic texts. While in some operas (such as Poppea) these kinds of political references, as we will see below, are evident through the censoring of some particularly notable words, there are also some explicit references to Neapolitan politics in Giasone, Veremonda, and Magie amorose. At the end of Giasone’s original prologue, sixty lines were added for the character Amore, who refers to the Spanish king’s newborn daughter, to the recent rebellions, and to the Naples viceroy (referred to here, as in the dedication, as “d’Italia il ver liberatore,” the true liberator of Italy). Moreover, the prologue to Veremonda contains many explicit references to Oñate and his relatives, who were meant to be part of the audience during the performances. Finally, in the prologue to Magie amorose, Oñate is named as the only possible competitor for the character Magia, for he “makes prudent those who are imprudent, and wise those who are foolish” (“ed egli è sol che rende | gl’imprudenti prudenti e savi i matti”).[41]

5.2 The companies’ self-promotion, too, took place within the printed librettos. First, members of the Discordati and Febiarmonici signed the dedication letters: Manara for Didone and Poppea, the Feboarmonico singer Giovanni Paolo Bonelli for Finta pazza, and Balbi for Veremonda and Magie amorose.[42] In addition, references to the “armoniosi accademici” and “armoniche scene” are very common in these dedication letters.[43] Among the most meaningful references to the performers are those linked to Manara and Balbi, and to their set designs and stage machines. In the dedication of the libretto for Didone, Manara calls himself “pellegrino architecto” (itinerant architect),[44] and in the prologues of Veremonda and Magie amorose, Balbi praises his own work as a set designer. In the former, during the dispute between the arts, he highlights Architettura’s superiority, for she is able to build a theatre onstage in front of the audience with a simple wave of the hand. Similarly, in the prologue to Magie amorose, the character Magia reduces a palace to rubble, and in its place allows the set of the drama to appear: the island of Corcira.[45] In this last opera the self-presentation of the performers is even more evident. Since Faustini and Cavalli’s Rosinda was heavily modified for performance in Naples under the new title, Magie amorose, Balbi added at the end of the libretto a detailed (although not entirely reliable) report about the creation of the modified opera. In this account, the leader of the Febiarmonici describes the process of manipulation that he and the Neapolitan poet Giulio Cesare Sorrentino performed on the original opera, giving an account of their choices in reshaping Rosinda, in a sort of closing letter to the reader underlining the new Febiarmonici authority of the work.[46]

6. Reference to the Performances

6.1 The Neapolitan texts also reflect manipulations that took place for performative reasons, mainly to adjust the operas for the new touring companies’ casts.[47] Generally, in texts related to revivals, we often see a different number of singers from the opera’s original cast, and in the case of Poppea, the Neapolitan libretto suggests an undermanned cast. For instance, in Act 1 at the transition from scene 2 to scene 3, only one of the two soldiers remains on stage. Soldato I has four new lines in which he explicitly sings that he has to leave (“mi parto a volo”), while the other must stay to wait for new orders from Nerone (“tu qui rimanti, intendi, | e nuovi ordini suoi fors’ora attendi”).[48] Most likely, the singer who performed Soldato I had to change costumes, because he probably also sang the part of Arnalta, coming back onstage in scene 4. The limited supply of singers also affected both of the old nurses’ parts: Arnalta and Nutrice. At the end of Act 1, scene 4, the Neapolitan libretto presents some new lines in which Arnalta affirms she is nurse for both Ottavia and Poppea (“… io che sono | d’Ottavia e di Poppea cara nutrice, | presupposta Poppea Imperatrice, | a lei salda m’appiglio …”).[49] This new combined part written in alto clef merged Arnalta’s and Nutrice’s roles,[50] with only one singer performing both—likely the one who sang Soldato I’s part and left the stage at the end of Act 1, scene 2.[51]

6.2 As already mentioned, in the Neapolitan sources a scene for Ottavia sola replaces the original Act 2, scene 7 for Nerone and Poppea. Therefore, after scene 6, Nerone must leave the stage, and in the Neapolitan score he closes his passage with the words “… lieto men vuo’ hor tra gl’amanti” (I go now, pleased, to be among the lovers ).[52] After this line, in both sources crafted in Naples we find the line, sung a due, “Di Neron, di Poppea cantiamo i vanti” (Let us sing the praises of Nerone and Poppea), which had been assigned to Petronio and Tigellino in the early version printed in Delle ore ociose by Busenello.[53] The poet’s early intention was to have these two characters sing the entire scene with Nerone and Lucano; however, in the scenario printed in 1643 on the occasion of the premiere, their parts were cut. Therefore, the Neapolitan sources restore their lines, although not their parts, and reassign them to Nerone and Lucano, the only characters onstage.

6.3 By contrast, in the libretto for Giasone printed in 1651, in Act 2, between scenes 6 and 7 of Cicognini’s drama, we find the addition of a whole new part for a new character: the page Erino. This young man sings about misogyny and fear of love, usual topics for a comic role, and his part is written in soprano clef. Very likely the singer of Erino’s part was also responsible for some other parts with the same vocal ambitus, such as for example that of Amore.[54]

6.4 The need to accommodate additional cast members seems to be the main impetus for the reworking of Rosinda as Magie amorose in 1653. In this case, the addition of the character Lindoro, son of the wizard of the story (Meandro in Venice, Poliastro in Naples), enriched Faustini’s already intricate plot. Apparently, according to Balbi’s letter to the reader, this new part was necessary in order “to suit the number of celebrated academics” available in Naples (“per adempire il numero di questi celebrati academici”). This change nonetheless affects the entire structure of the opera. Indeed, Lindoro sings many new parts and contributes to the final couples’ symmetry, with the addition of a new pair, Lindoro-Cillena, to the original Venetian ones: Tisandro-Rosinda and Clitofonte-Nerea (plus the unstable comic threesome of Aurilla, Vafrillo, and Rudione).[55]

7. Censorship in the Neapolitan Librettos

7.1 Outside of Venice, the original librettos, so steeped in the libertine concepts that characterized the Accademia degli Incogniti, needed to be “sanitized” for a more acceptable final product.[56] As mentioned above, Egisto, Giasone, and Finta pazza—based on versions the touring companies had already given elsewhere—do not present any uniquely Neapolitan instances of censorship. In the other texts printed in Naples we find the results of an expurgation process that involved at least three main elements: morality, religion, and politics.[57]

7.2 The Neapolitan sources for Poppea avoid a number of sexual references through replacements and deletions (often with ellipses in the printed libretto). In the libretto, we find numerous cases of substitutions of sensitive words inherited from earlier sources. Moreover, many of the libretto’s unique variants could have occurred either in 1651 or before, as for example the substitution for the word “seno” (female breast) by “viso” (face) in line 98, and the amendment to the passage in which Drusilla, ready to give her clothes to Ottone for Poppea’s murder in disguise, sings that she is going to get undressed. In this case, the Venetian lines “Andiam pur ch’io mi spoglio | e di mia mano travestirti io voglio” (Let us go, so I can disrobe and disguise you with my own hand: Act 2, scene 11, lines 1163–64) were replaced with “Andiam, ch’io, come soglio, | di propria mano travestirti or voglio” (Let us go, because I wish to disguise you with my own hand as I usually do). The reference to undressing, “ch’io mi spoglio” (so I can disrobe), is replaced by the more neutral “come soglio” (as I usually do).

7.3 We find the same concern in the libretto for Didone, where in Act 3, scene 1, for example, “trastulla il corpo” (amuse your body) is replaced by “stia lieto il corpo” (let the body be happy), and “vada la castità” (banish chastity) by “vada l’angoscia pur” (banish distress). Elsewhere in the same opera, in Act 3, scene 2, the end of the passage “dove starò meglio … | che tra gl’ameni colli | de’ vostri seni amorosetti e molli?” (Where can I feel better … if not among the pleasant hills of your lovely and soft bosom?) is replaced by “di questa patria verdeggianti e molli”—thus, the hills of a bosom by the hills of the countryside. Moreover, in the Neapolitan libretto for Veremonda, a number of alterations involve the scenes with the witty Amazon Vespina, Veremonda’s lady-in-waiting (whose name in Naples is Callidia). During her dialogue with the soldier Zeriffo in Act 1, scene 7, some explicit sexual allusions were changed. For example, the passage “[meglio faresti] di esser tutta mia la notte e ’l dì” is replaced by “[meglio faresti a] non stancar il piè la notte e ’l dì.”[58] Similarly, in Act 1, scene 10, Vespina reacts to Zeriffo’s attempt to whisper in her ear by singing “Oh scusa bella | per toccarmi una guancia!,” but in Naples the reference to her body was replaced by “O scusa bella | per tacerne gran parte.”[59] Finally, her remark “tutta tutta sarò con la persona | la tua mogliuccia buona” was replaced with “al candido aspettar de la tua fede | darassi la mercede.”[60]

7.4 One of the main motives for the revisions outside of Venice seems to be the theological contents. In the Neapolitan libretto for Poppea we see a number of changes, such as “peccati” (sins) replaced by “diletti” (pleasures), “miracoli” (miracles) by “maraviglie” (wonders), “beato/a” (blessed) by “felice” (happy), but also deletions through ellipses when words such as “Paradiso,” “coscienza,” “peccato,” and “beato” (heaven, conscience, sin, blessed) occurred in the text.[61] Some lines were entirely deleted when their meaning was perceived as too passionate, as for example when Ottavia, railing against the god Jupiter, sings in line 269, “d’ingiustizia t’incolpo” (I blame you for injustice), and, analogously, at line 485, when Nerone sings that he had lost his own “spirto infiammato” (inflamed spirit) after kissing Poppea.[62] Finally, it is very likely that Act 2, scene 4, depicting Seneca’s suicide, is absent from the Neapolitan libretto because its content is contrary to the Catholic faith.[63]

7.5 A similar treatment of theological material appears in the Neapolitan text for Didone, where lines and scenes concerning the afterlife and spirits were cut, and words referring to idolatry and religious concepts were replaced.[64] For example, in Act 2, scene 1 the adjective “divin” (divine: referring to Didone’s face) is replaced by “gentil” (gentle); and in Act 1, scene 3, the sentence “[la tua destra puote] in alma e in corpo ancor condurmi in cielo” (your hand can bring me to heaven in both soul and body) is replaced by “[la tua destra puote] darmi a veder più luminoso il cielo” (your hand lets me see a brighter sky). In Veremonda, too, some lines were rewritten to avoid theological allusions, as for example in the second aria for the king of Aragon in Act 1, scene 5: “Riformar a voglia mia” | s’io potessi la natura.” In this piece the king, also an astrologer, suggests that he would have been better than God in shaping the world. In the Neapolitan libretto the piece was radically changed and the order of the strophes inverted, to delete the heretical reference.[65]

7.6 Together with the religious element, politics is at the center of the revisers’ attention outside of Venice. Since in Poppea the references to the nobility and to political power are very frequent and usually express a generally negative view, in many cases the Neapolitan libretto presents censored words. For example, it substitutes ellipses for the words “regi” (kings), and above all “grande” or “grandi” (big), which could refer to the title “Grande di Spagna” (grandee of Spain), given by the Spanish king to nobles distinguished for particular services.[66]

7.7 In this regard, a certain moralizing attitude among Poppea’s revisers is also evident in the treatment of Ottavia’s part. The new centrality of this character in the Neapolitan version is well known. Not only does the dedication letter of the libretto clearly focus its attention on Nerone’s wife, but the addition of new sections also reinforces her importance.[67] Nonetheless, the content of the new passages seems to have been overlooked until now, and together with the libretto’s paratexts, seems to clarify a hidden aim behind the manipulation of the opera.

7.8 In the dedication letter, Manara asks the viceroy to welcome Ottavia as a personification of the entire opera and depicts her as a character in danger and in need of protection.[68] From this text, the empress appears to have lived through so many “misadventures” (“disavventure”) that she deserves to come “back to her status” (“nel suo pristino soglio”) before Nerone’s disavowal. Indeed, Manara refers ambiguously to both the queen and the opera itself; nevertheless, the added poetic and musical materials confirm this positive view of the character, while in all other sources for the opera, she is clearly as despicable as the others. The only two sections for Ottavia added in Naples are a ten-line aria inserted after line 272 (in Act 1, scene 5 for Ottavia and Nutrice), and the aforementioned lament scene that replaces the love scene for Nerone and Poppea (Act 2, scene 7) in both the Neapolitan libretto and score.[69]

7.9 The main topic for the new aria is Ottavia’s jealousy, which is conveyed through a series of sentences that cast her in a positive light. After having blamed the gods for what Nerone is doing to her, apart from the deletion of some strong declarations against them (as we have already seen above),[70] Ottavia expresses some repentance for what she has just sung. She suddenly blames herself for her own words, remembering that her royal status should hold her far above such ill-bred sentiments: “mal conviensi a regio core | negli oltraggi inlanguidire.”[71]

7.10 Analogously, the new lament scene (Act 2, scene 7) depicts Ottavia as unexpectedly and genuinely in love with her husband. We need only consider that her line “rendimi il mio marito” (give me back my husband), directed to Poppea, closely resembles Deidamia’s true desperation in Finta pazza, when she invokes her “senno ingegnoso” (ingenious wisdom), asking of it: “rendimi il caro sposo!” (return to me my dear husband, i.e., Achilles).[72] In Ottavia’s new scene, she appears more desperate than bloodthirsty, and deeply in need of Nerone’s love. Furthermore, the new text emphasizes the illegitimacy of Nerone and Poppea’s affair, mainly when Ottavia sings that she wants a sword to cut the thread of their unchaste love and to kill their villainous hearts, with the words: “farò che ’l ferro giunghi | a recider lo stame | d’un affetto impudico, un petto infame.”[73] Moreover, she overtly shows her need for just vengeance, singing that “an avenged offense appeases the wounds, it soothes the pain, and beyond the hidden injury, it renders the scar more glorious” (“vendicat’offesa | … | disacerba la piaga, | mitiga il duolo e fuor d’ingiuria ascosa | rende la cicatrice più gloriosa”).[74] With these shrewd adjustments Ottavia’s role underwent a moral switch: her part not only became longer and more important, but also more socially acceptable. In the Neapolitan sources, then, Poppea now contained a character with whom any new audience, far removed from the libertine culture of Venice, could easily empathize, since it presented features unanimously accepted in Italian court society, so profoundly Catholic.[75]

7.11 Two characters in Veremonda’s Neapolitan libretto seem to have been treated the same way: the king of Aragon, and Delio, the general of the Aragonese army. In the Venetian libretto they are depicted through an ironic lens, in line with Strozzi’s style; but in Naples their roles switch toward a positive characterization. Act 1, scene 8 begins with an aria for Delio, in which he complains about the difficulties of being handsome with the words “Gran tormento è l’esser bello.”[76] In the meantime, Vendetta (Vengeance) ironically comments on what she is hearing, but in the Neapolitan libretto her tone appears intentionally softened.[77] Moreover, in this source, ten new lines express Delio’s desire to regain his honor and to avenge the injuries he suffered in the past. This passage begins with the typical spur to action for a heroic solo scene, in evident contrast with the aria focused on vanity he sang at the beginning of the scene.[78] Furthermore, this addition contributes to clarifying Delio’s real intentions and to ennobling his character, which in Venice was depicted more as a ridiculous dandy than a leader of the Aragonese army.

7.12 At the end of Act 2, scene 7 the same libretto presents an additional aria for the king of Aragon that reveals his doubts about his wife Veremonda’s loyalty. After indulging in his jealousy, in the third strophe he regrets having suspected her (she is not actually betraying him), and he overtly states that jealousy is dangerous and inappropriate for a king.[79] The extension of his role through this aria was aimed at providing him with more kingly features: evidently he, more than any other character in the 1650–1653 Neapolitan productions, could symbolize the Spanish dynasty in the Neapolitan audience’s eyes.[80]

PART THREE: Reliability and Origins: The Text in the Neapolitan Sources for Poppea

8. The Texts’ Status

8.1 Taking into consideration all of the extant sources for each opera performed in Naples in proximity to Poppea allows us to better understand the nature of the Neapolitan librettos and scores. More importantly, this comparison helps us identify the relationship between these Neapolitan sources and their hypothetical antigraphs (i.e., copy-texts). These librettos and scores, indeed, show a strict connection to their Venetian roots through the mediation of the performance materials that the Febiarmonici brought with them from their previous tours. Nonetheless, the Neapolitan readings of these operas show a number of passages taken from multiple and different sources, revealing a certain reintegration process, and a general tendency toward hybridization, intentionally aiming at the creation of the best text possible.

8.2 The Neapolitan sources present texts that vary greatly in terms of accuracy. Although the score of Poppea is a neat copy, its text underlay is one of the most problematic in the opera’s textual tradition. It appears generally very corrupt, and not because of its antigraphs’ problems, but because of its copyist’s sloppiness. Excluding the variants and the mistakes inherited from earlier textual layers, the score presents a number of autonomous and unique alterations that heavily undermine its text’s intelligibility. In most cases, these problems seem to originate from the copyist’s struggles to understand another’s handwriting,[81] but many mistakes are caused simply by carelessness. Sometimes the copyist forced together suffixes for words that do not concord;[82] he often added final syllables to words shortened by elision,[83] or omitted some words (or parts thereof), even after having copied the corresponding musical notes.[84] There are cases in which he twice repeated half a line and then forgot the rest,[85] or, in long melodic passages, he realigned the text under the notes, often after adding or deleting words or syllables.[86]

8.3 Similarly, in the other Neapolitan music source, the score of Giasone, the poetic text appears highly corrupted. Although this manuscript was accurately copied, the text reveals a number of mistakes added to the several problems already inherited from its antigraphs. We find the same situation in the texts of the other six operas’ printed librettos, which are not very tidy. They often present typos and mistakes that affect the text’s intelligibility, as for example the editions of Didone and Finta pazza, the former of which contains many typographical problems, possibly related to a hasty print.[87]

8.4 The textual accuracy of the Neapolitan libretto for Poppea is very different from that of the score. This text does contain a few mistakes, but in general is very refined.[88] The person in charge of revising the text to be given to the Neapolitan publisher worked toward specific results through a process of fine-tuning that was independent, with respect to the other sources for the same opera.[89] Nevertheless, in determining the status of each text (i.e., its position in a textual genealogy), the question of accuracy does not affect reliability. Indeed, the mistakes and textual sloppiness are superficial components and tell us little about the texts’ true nature. Only the comparison of variants and mistakes in all the extant sources for each libretto can give reliable results in terms of textual origins. Therefore, before entering the minefield of Poppea’s variants in order to retrace backwards the evolutionary path of the two Neapolitan readings, it is worth contextualizing the latter among the other thirteen known sources for the opera.

9. Poppea’s Textual Traditio

9.1 The relationship between the extant sources for Poppea cannot be given definitively since it is very intricate and in some cases incongruent. However, the fifteen extant sources for the opera—two scores, one scenario, and twelve librettos—can be divided into families, some preceding and others following the 1643 Venetian premiere.[90]

9.2 According to some recent scholarship, the very first textual status for Poppea is to be found, paradoxically, in the 1656 print of the libretto, inserted among the other dramatic works by Busenello in his collection Delle ore ociose.[91] Although late, this publication seems to offer a very early reading, preceding any interventions by the composer. In addition to a handwritten copy of it, recently come to light in Milan, the text in this print formed the basis for at least seven other manuscript librettos, divided into the so-called groups vulgata I and vulgata II.[92] The text in the sources in these two groups shows very early signs of influence of the musical setting on Busenello’s work, and presents the typical characteristics of a textual vulgata lectio (i.e., a commonly accepted reading). These manuscripts contain the most widespread reading of the libretto (seven sources out of fifteen), and they seem to derive directly from a text that began to circulate in manuscript form soon after the composition of the music, perhaps because no libretto seems to have been printed for the premiere. The first group, vulgata I, is made up of five librettos: three preserved in Rovigo, Warsaw, and Venice, in addition to a fragment of the first act held in Udine, and the recently discovered libretto at the Biblioteca Riccardiana in Florence.[93] The second group, vulgata II, contains only two librettos, held in Treviso and at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence.[94] The text in these latter sources, though very close to that of vulgata I, shows a later reworking due to the influence of the version that was staged in 1643, as reflected in the scenario printed in Venice for the premiere, and in the complete manuscript libretto held in Udine.[95]

9.3 The scenario, bearing the year of the premiere, and the Udine libretto are considered the earliest surviving sources directly connected to the first Venetian production. They are therefore strictly linked to the hypothetical score that must have existed for the first performances; and they probably comprise the reworkings that occurred for the premiere. Thus, they share a certain scenic structure, the presence/absence of specific characters, and some elements of the plot that are markers for understanding the proximity of the other sources to the 1643 Venetian production.[96]

9.4 The last group comprises four sources produced around 1650 and linked to various revivals: the score held in Venice, the Neapolitan score and libretto, and a manuscript libretto held in Hanover. The presence of the handwriting of Francesco Cavalli’s wife in the Venetian score dates it from 1650 to 1652, at least seven years after the opera’s premiere.[97] Yet its close relationship to the text of the complete Udine libretto suggests that it contains a reading directly linked to that of the lost 1643 score;[98] nevertheless, it shows an evident adaptation process through a number of corrections, cuts, replacements, and reworkings. It is clear that the Venetian score was copied for an as-yet-unidentified revival, and above all, that Cavalli’s cast was different from the one provided for the earlier performances.[99]

9.5 Finally, the recently discovered manuscript libretto in Hanover shows yet another reading of the dramma, probably linked to an unknown production that took place before 1655.[100] This source includes several extensive cuts often explicitly noted by the copyist, who heavily pruned the text of his antigraph, deleting single lines as well as entire scenes.[101] Furthermore, it reflects the influence of the librettos of vulgata I, together with some variants so similar to those in the Venetian score that it seems to copy from this source, or from another very close to it.[102]

10. A Score as a Principal Antigraph

10.1 As is the case for the libretto in Hanover, for both the Neapolitan sources the most influential direct antigraph was a music source. The reading in the Naples score presents a general connection to the one in the Venice score (though neither is a copy of the other), with which it shares unique common variants and mistakes.[103] Moreover, along with some common word replacements shared with the Hanover libretto as well,[104] the two scores have in common additions and cuts, the same word inversions within a line, and the same replacements and repetitions of entire passages.[105]

10.2 Unlike the Neapolitan score, the origins of the libretto printed in Naples are more surprising. The many correspondences with both scores suggest that it was very likely based directly on a musical source, although not one of the surviving two.[106] Apart from sharing simple words that differ in all the other sources,[107] these three sources also have in common displacements and repetitions,[108] and above all they present typical musical structures in the dialogues, characterized by repetitions and broken lines, which the Neapolitan libretto sometimes reports with precision, as for example in lines 192–93 at the end of Act 1, scene 3. Table 1 shows three readings. Busenello’s libretto printed in 1656 has only two settenari for Poppea and Nerone (1); however, in the musical sources and in the Neapolitan libretto (2) we find a structure expanded by a series of short repetitions, which, although slightly different, is also present in the manuscript libretto held in Udine (3).[109]

10.3 In the Neapolitan libretto we find another very interesting phenomenon related to its likely musical antigraph. Indeed, when comparing it to the other sources, in some passages we notice that the copyist who prepared the manuscript libretto for the publisher had to extract the lines from a source that had no metric regularity, namely a score. This is very evident in cases such as the lines “è destin che necessita: son pronto | a servirti, o regina” (Act 2, scene 9), where the textual tradition of Poppea splits in two, as shown in Table 2. In this passage, the libretto printed in Venice in 1656 and the manuscript librettos of vulgata I (1) present an endecasillabo and a settenario with the verb “servirti” (to serve you). Conversely, we find the variant “ubbedirti/ubbidirti” (to obey you) in the complete libretto held in Udine and in the manuscript librettos of vulgata II (2), but also in the manuscript libretto held in Hanover (3), in the two scores (4), and finally in the Neapolitan printed libretto (5). Very likely, the libretto printed in Naples inherited the verb “ubbidirti” preceded by the preposition “ad” from a score linked to group (4). However, since this reading includes an ottonario, out of place in versi sciolti, the person responsible for the Neapolitan text decided to reshape the two lines in order to obtain a regular metric succession that reverses the original structure: a settenario (in this case, a settenario sdrucciolo) followed by an endecasillabo.

10.4 Something similar happened in a three-line addition after line 1396 (Act 3, scene 4), which we find in all the sources except the 1656 print and the manuscript librettos of vulgata I: “Io fui la rea | ch’uccider volli | l’innocente Poppea.” See Table 3, where we retain the numbering of source traditions established in Table 2. Two quinari and a settenario are found in the Udine and Hanover librettos as well as in vulgata II (2, 3), while in both scores, we find the repetition of the word “io” (4), resulting in a metrically ambiguous verso plus a quinario and a settenario. The Neapolitan reviser apparently decided to normalize his musical antigraph’s reading, introducing versi sciolti by repeating the first two words, “Io fui” (I was), and combining the first two lines, thus creating an endecasillabo plus a settenario (5).[110]

10.5 The relationship between the Neapolitan libretto and its musical antigraph is confirmed by the variants that the former shares only with the Venetian score. These elements occur in passages in which the Neapolitan score altered the text inherited from its own antigraph, while the score from which the Neapolitan libretto was copied presented a reading—similar to that in the Venice score—that preceded those alterations.[111] Finally, the relationship between the Venetian score and the two Neapolitan sources is strengthened by the libretto held in Hanover, which shares a number of common elements with them.[112]

11. Early Performative Traces

11.1 As we mentioned above, these four sources—the two scores, the Naples libretto, and the Hanover libretto—also show a close kinship with the surviving text closest to the 1643 premiere: the Udine complete libretto. First of all, the Neapolitan sources present some unique conjunctive variants with this libretto,[113] and the number of common concordances rapidly increases when we connect their three texts to the one in the Venetian score (sometimes also adding the Hanover libretto into the mix).[114] Apart from a relatively small number of unique word concordances,[115] the strong connection among these sources reflects the reshaping process that affected the libretto during the composition of the music. The most important difference between this group and all the other sources, indeed, is the manipulation of many passages in order to make the characters’ utterances more intertwined. A clear example of this phenomenon, shown in Table 4, occurs at the transition in Act 1, from scene 1 to scene 2: “Ottone: … | ma l’aria e ’l cielo a’ danni miei rivolto | tempestò di ruine il mio raccolto. | Soldato I: Chi parla, chi va lì?” Indeed, in the Neapolitan sources, the Venetian score, and the libretto in Udine (2), these three lines acquire a theatrical effectiveness absent in Busenello’s 1656 text (1).[116]

11.2 Another peculiar manipulative process that we find in these four sources is frequent line repetition and displacement. Apart from the simple reiterations of entire lines or parts of them, among the most interesting cases are the passages in which, due to the composer’s choices, the insistence on a character’s line reflects a sort of obstinacy, which is very effective from a theatrical point of view.[117] For example, this happens in the first part of line 188, Poppea’s “tornerai?” (will you come back?) directed at Nerone, which she anticipates and repeats after lines 181, 183, and 185 in these four sources.[118]

11.3 The strong relationship that connects the Neapolitan sources to the 1643 text can also be traced in some passages that the Neapolitan sources, the Venetian score, and the libretto in Udine have in common only with the two librettos in vulgata II. These two manuscripts, as already mentioned, share with the Udine libretto and the printed scenario some variants related to the 1643 production, as for example in the excerpt from Act 3, scene 4 shown in Table 5. In lines 1395–99 these six sources and the libretto in Hanover (2), compared to Busenello’s original text (1), share a number of repetitions and interpolations that further connect the Neapolitan sources to the opera’s performative origins.

12. Hybridization toward an Enhanced Text

12.1 A considerable process of textual reintegration that involved both Neapolitan sources somehow weakens their direct link to the sources close to the 1643 premiere. In fact, the Neapolitan libretto and score contain passages from a variety of sources: in the 1651 texts, various readings have been combined, with the apparent aim of producing the most “complete” text, and perhaps of reconstructing the librettist’s original intentions.

12.2 The Neapolitan libretto contains several passages in which somebody clearly contaminated the text inherited from the musical antigraph. The antigraphs for this process could have been one libretto with Busenello’s early version and another with the text of vulgata I, or simply a single source that had already mixed the two versions. For this reason the Neapolitan libretto shows variants close to the 1656 edition and vulgata I,[119] or sometimes just one or the other.[120] Moreover, it omits some lines, some line attributions and displacements, and some of those peculiar manipulations of the dialogic passages found in the scores and in the 1643 version (as reflected in, for instance, the Udine libretto).[121]

12.3 The same process is visible in the Neapolitan score, which shows many passages with evident traces of hybridization.[122] Sometimes the copyist modified the underlay, mixing the readings he found in different sources,[123] and replacing the words he had already copied with others from a source he considered more reliable.[124] Moreover, this score shows another type of strong proof of this hybridization phenomenon. Along with the Venetian score, the Neapolitan one contains no music for lines 1258–67, very probably because they were absent in its musical antigraph. However, the copyist reveals that at least one of his sources (perhaps a libretto) contained those lines, since he left eight staves blank (fols. 89v–90r), with the apparent aim of later filling them in with new music.[125] Further evidence for this hybridization process is in the length of the words. From a non-musical source the copyist adopted the long version of words that were shortened for musical reasons, giving them in complete form even if there were no additional notes to accommodate the added syllables.[126]

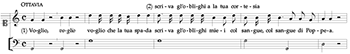

12.4 The tendency toward a text closer to a libretto than to the one in the musical antigraph is also evident in several apparent line restorations in the Neapolitan score. For example, in the musical setting for Ottavia’s lines 1028–31, “Voglio che la tua spada | scriva gl’oblighi miei | alla tua cortesia | col sangue di Poppea: vuo’ che l’uccida” (I want your sword to write with Poppea’s blood my gratitude for your courtesy: I want you to kill her), line 1030, “alla tua cortesia,” is absent in the Venetian score, in the Udine and Hanover librettos, and in vulgata II, and it very likely did not appear in the musical antigraph of the Neapolitan score either. Indeed, after copying the notes, the Neapolitan copyist inserted the restored line from a libretto, taking advantage of a text repetition within line 1031 in the musical source (“col sangue, col sangue di Poppea”). See Example 1. However, the line did not fit with the notes already copied, and thus produced an incoherent passage, impossible to sing.[127]

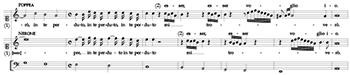

12.5 Similarly, the Venetian score and vulgata I provide the irregular reading of line 1485, “che sempre in te perduto mi troverò” (always lost in you I shall find myself), while all the other librettos have “che sempre in te perduta/perduto esser vogl’io” (I want to be lost in you). The Neapolitan score merges the two versions: “in te perduto mi troverò, in te perduta esser voglio io.”[128] However, as Example 2 shows, these new lines do not fit the music, which is identical to that in the Venetian score. It seems that the Naples copyist tried to enhance the passage found in his musical antigraph. He adopted the words “esser voglio io” from a libretto, in order to restore the rhyme with the preceding line, “e tornerò a riperdermi ben mio” (and I will lose myself again, my beloved), taking advantage of the final textual repetition (and abundance of music) in the antigraph. The result, however, is a messy passage with no correspondence between words and music.

12.6 The two Neapolitan sources also share many word and line displacements with the 1656 print and vulgata I.[129] Most interesting among their common variants, however, are the completions that, in comparison to the Venetian score, result in new music in the Neapolitan score. (A complete list of the vocal pieces present in the Neapolitan score and absent from the Venetian one is found in Appendix 3.) Most of the lines set to music in the Neapolitan score and absent from the Venetian one are inherited from an early text close to that in the 1656 print as well as the vulgata I group. Therefore, they belong to a reading that precedes the manipulations that occurred for the 1643 premiere (visible in the Udine libretto and sometimes in vulgata II).

12.7 In general, it is likely that these passages that were set to music at a later stage in order to “complete” the score with the “missing” parts, had the effect of an enhancement more than a restoration. In fact, apart from the lament for Ottavia present only in the Neapolitan sources (Act 2, scene 7; see par. 3.4 and 7.10 above),[130] among the vocal pieces with music present only in the Neapolitan score, nine out of the seventeen are absent not only from the Venetian score, but from the Udine libretto and vulgata II as well;[131] four other passages are missing only from the first two sources.[132] In general, the absence of these thirteen passages from both the libretto closer to the 1643 premiere and the Venetian score suggests that they had already been cut by the time of the first performances, or even had not been set to music at all in 1643. In our opinion, the general features of the text in the Neapolitan score confirm that the new pieces were added rather than restored from a musical antigraph.[133] In fact, the text in the Neapolitan score belongs to the same textual branch as the other score and the Udine libretto, and the elements it shares with the 1656 edition and vulgata I were clearly added to its original textual layer. Cases such as word erasures and replacements, together with the gap for lines 1258–67 in fols. 89v–90r, suggest that during the revision stage, the score was provided with many additions: not only single words and lines, but also entire pieces.

12.8 Nevertheless, the Neapolitan score contains music for at least three pieces that could have different origins from those just discussed. The first one appears at the end of the opera, after Venus’s last line (1594), which in this score, in the Udine libretto, and in vulgata I is followed by eight lines a due for Poppea and Nerone, “Sù! Venere ed Amore.”[134] This is the only case in which the Neapolitan score inherits a piece absent from both the Venetian score and the 1656 print, while it survives in sources from different families. Its presence in the Udine libretto suggests that it was sung in Venice in 1643, and therefore, that a musical piece with those lines could have existed and been inherited. The surviving music in the Neapolitan score, however, is hard to attribute, due to the complexity and the inconsistency of the opera’s music; therefore, the Neapolitan piece could have been composed after the 1643 Venetian performances and belong to a later stage of development.[135]

12.9 The same assumption is valid for two other vocal pieces whose music is present only in the Neapolitan score: a passage in Act 1, scene 11 for Ottone (“Ahi, chi ripon sua fede in un bel volto”),[136] and an aria for Ottavia at the end of Act 2, scene 9 (“Mora, mora la rea!”).[137] The first passage is absent in all sources except the Neapolitan ones, the 1656 print, and the libretto held in Udine; while the second is in the Neapolitan sources and in vulgata I only. Therefore, their texts could have appeared in 1643. However, though these texts could have been sung in Venice, we cannot know whether the music was the same in Naples.

PART FOUR: Authorial Issues and Performative Traces in the Neapolitan Sources for the Other Operas

13. Venetian and Neapolitan Authors

13.1 The main textual tendencies we highlighted in Poppea are also traceable, if inconsistently so, in the sources for the other operas performed in Naples during the same years. Indeed, due to their Venetian origins and the subsequent manipulation and transmission by the touring companies, some of these six works reveal an unexpected closeness to the Venetian surviving sources, while others stand out for their role in transmitting and spreading the touring versions of the opera.

13.2 As an authorial statement, the letter of dedication found in the libretto for Finta pazza, published in Naples in 1652 and signed by the Feboarmonico singer Giovanni Paolo Bonelli, is perhaps the most controversial among those in the seven Neapolitan printed sources. A clear reference to the work’s original author, Giulio Strozzi, appears on the title page;[138] however, this need to demonstrate the authority of the libretto printed in Naples contradicts its contents. After publishing his text twice in 1641 for the Venetian premiere (editio princeps and “seconda impressione”), Strozzi signed another edition in 1644 (“terza impressione”), and in this print he complained about some unauthorized editions of his work.[139] In the Letter to the Reader, he clearly declares that some touring companies were publishing his work outside of Venice with many changes and without his agreement.[140] Very likely, he was referring to the heavily revised edition that the Febiarmonici published in 1644 for their revival of Finta pazza in Piacenza, which, as we will show below, was the direct antigraph for the Neapolitan libretto.[141]

13.3 After Finta pazza, the Febiarmonici published in Naples the other dramatic text by Giulio Strozzi, Veremonda. However, as in the libretto printed in Venice, in Naples the poet’s name appeared in the anagram “Luigi Zorzisto.”[142] We do not know why in this case Strozzi’s authority was hidden, but it is also worth noting that the source of the plot went undeclared as well: Celio by Giacinto Andrea Cicognini.[143] Nor is there any mention of the Neapolitan revisers for the text and the music, although the libretto was heavily modified in respect to the Venetian one (in order to fit the circumstances of the performance).[144] However, on the libretto’s title page we find an acknowledgment of the Venice-Naples operatic axis, with the name of the Venetian composer Francesco Cavalli followed by that of one of the touring company’s leaders, Giovan Battista Balbi.

13.4 The case of Magie amorose, printed in 1653, confirms this concern for authority. Although, in comparison to the Venetian editio princeps (1651), the Neapolitan libretto presents a heavily manipulated text as well as a modified title, it nevertheless contains an unexpectedly strong statement about its Venetian origins. On the title page it presents the names of two of its Neapolitan revisers, the poet Giulio Cesare Sorrentino as well as Balbi, and in Balbi’s Letter to the Reader, we learn of the impact of the Neapolitan reworking on the original text. Here Balbi explicitly identifies Magie amorose as a remake of the Venetian Rosinda, and states that the original opera was adjusted for performative reasons (mainly to adapt the plot to the new cast: see par. 6.4 above).[145] Although he hides the names of the opera’s original authors (Faustini and Cavalli), as we will see below, analysis of the Neapolitan text reveals that he had access to some materials very close to them.

14. Neapolitan Librettos and Venetian Scores

14.1 In some Neapolitan librettos we find many elements that connect their texts to the surviving Venetian scores and place them high in the stemmata codicum of their respective textual traditions. Confirming the assumption that recentiores non deteriores, the Neapolitan texts in many passages show the most correct readings and allow us to correct mistakes in the editiones principes printed in Venice.

14.2 For example, the Venetian score for Veremonda shares a general early version of the text with the libretto printed in Venice. The latter, however, shows some subsequent manipulations that appear neither in the score nor in the 1652 Neapolitan print. In fact, the libretto published in Naples, although probably printed after the Venetian one and full of evident later manipulations, preserves some early readings present in the score, and shares a number of variants with Celio—the oldest hypotext (source text) for Veremonda.[146] These elements suggest that the text in the Venetian libretto, although early, contains modifications and corruptions. In some cases, moreover, the score presents the same erroneous reading as that of the Venetian libretto, while the Neapolitan one shows the correct version (usually derived directly from Celio).[147]

14.3 As regards Magie amorose, comparison between the Neapolitan libretto and the only two other extant sources (Cavalli’s autograph score and the editio princeps) reveals a link between the text printed in Naples and Cavalli’s score preserved in Venice. With respect to the 1651 Venetian libretto, in fact, the two sources present common disjunctive elements. First, apart from some banalizations,[148] they share absences, which reveal that since Cavalli never wrote the music for some lines found only in the Venetian libretto, they could have been added to the text to be printed after the composer had finished setting the text to music.[149] They also share some variants and the correct forms of some words that appear wrong in the Venetian print.[150] In addition, only in these two sources do we find, in Act 1, scene 2, an entire aria absent from the Venetian editio princeps: “Auretta soave” for Rosinda with an ending a due with Clitofonte.[151]

14.4 Although no libretto was printed in Venice for the 1641 premiere of Didone, the collatio of this opera’s extant sources, in addition to challenging some recent theories about its textual tradition, seems to produce results very similar not only to the ones presented here for Veremonda and Magie amorose, but also to those for Poppea. The Neapolitan libretto of this opera was published most likely in 1650, and consequently it is the oldest surviving printed text of the opera. In fact, only the Argomento e scenario had been printed in 1641, and the first Venetian print of the libretto appeared only in 1656, in Busenello’s Delle ore ociose.[152] Due to common line gaps and some textual variants shared exclusively by the Neapolitan text and the extant Venetian score, a derivation of the music source from the version staged in Naples in 1650 has recently been postulated.[153] In our opinion, however, the sources for Didone are related to each other in a different way, and the Neapolitan source could have played another role.

14.5 On the one hand, the surviving score and one extant Venetian manuscript libretto show a number of common elements likely linked to the composition of the music and to some early productions.[154] On the other hand, for textual reasons, the 1656 print and the manuscript libretto held in Florence seem to contain the earliest surviving texts for this opera, both linked to a very early version by Busenello.[155] The Neapolitan libretto, as in the case of Poppea, seems to bridge the two branches of this textual tradition. Indeed, apart from the elements in common with the score, it also shows many variants present in the 1656 edition, in passages where the score and the manuscript libretto held in Venice (and sometimes the Florentine one as well) show a different reading. The libretto printed in Naples shows traces of an active collation, wherein the texts of two different antigraphs were mixed (we do not know whether in Naples in 1650 or before). Therefore, its text is linked to the two distinct Venetian traditions, both the performative one and the one related to the librettist’s early intentions; in passages where it displays the same reading as the score (usually present also in the Venetian and Florentine manuscript librettos) it allows us to correct mistakes and misprints occurring in the 1656 edition.[156]

15. The Touring Companies’ Manipulations

15.1 Some of the Neapolitan texts share a number of variants and mistakes with the librettos printed by the touring companies before arriving in Naples. In the cases of Egisto and Finta pazza, this phenomenon is so strong that we find almost no manipulations added in Naples, and their texts are mere links in a textual chain. Compared to the previous sources, these two librettos’ few additions or modifications seem not to have occurred in Naples, and undoubtedly did not affect the subsequent productions.

15.2 The Neapolitan libretto to Egisto presents only a few differences with respect to the Venetian editio princeps printed in 1643, and some of them already appeared in the librettos linked to the first Febiarmonici performances (such as the ones in Florence and Bologna, in 1646 and 1647 respectively).[157] The same occurred with Finta pazza, but in this case, the relationship between the Neapolitan text and the earliest surviving Febiarmonici editions is much stronger. After the revival in Piacenza in 1644, the touring companies kept performing the opera. Between the libretto for Piacenza (mentioned above, par. 13.2) and the one for Naples, they printed at least five other editions: in Bologna (two different prints from 1647), Genoa (1647), Turin (1648), and Milan (undated, [1647–1651]).[158] Among all of the surviving sources published before 1652, the reading of Finta pazza in the Neapolitan source shows direct contact with only the Feboarmonico editio princeps printed for Piacenza in 1644, and does not contain any variants from the other editions.[159] Finally, the Neapolitan text contains only a small addition that we do not find in any other source: a third strophe for the protagonist Deidamia’s aria in Act 2, scene 4, “No, no, amar vogl’io” (“No, no, I want to love”).[160]

15.3 In contrast, the libretto and the score for Giasone both inherited a variety of Febiarmonici manipulations, including added materials that we find later on in subsequent productions. The libretto for Giasone published in Naples in 1651 reveals a strong relationship with the previous Febiarmonici editions, since it presents some modifications (such as line substitutions, line and scene cuts, and textual variants) that had already appeared in 1650 in Florence.[161] The most important among them is the aria-lament for Isifile, “Lassa, che far degg’io?,” which replaces part of her monologue in the penultimate scene of the first act in Cicognini and Cavalli’s version of 1649, and is also present in the Neapolitan score related to the 1651 performance. On the other hand, the libretto also presents modifications that very likely occurred in Naples (such as the lines in the Prologue that refer to the Spanish royal family, mentioned above in par. 5.1).[162] Some other additions, like the comic scene with the page Erino (Act 2, between scenes 6 and 7 of Cicognini’s drama), appear for the first time in Naples but could have originated earlier.[163] This scene entered very early into the Neapolitan performance tradition of Giasone, where it remained: we find it in one of the two later Neapolitan scores, and in all subsequent librettos printed in Naples or linked to the city.[164]

15.4 Finally, the influence of the Neapolitan texts on subsequent ones also appears in the textual tradition of Didone. Indeed, with respect to the Venetian sources, the 1650 Neapolitan libretto presents for the first time a number of manipulations that also appear later on, as for example in the texts printed in Genoa in 1652 and in Piacenza in 1655.[165] It appears that the version staged in Naples had an impact on the performative tradition of the opera after 1651. Still, another phenomenon could have occurred. Since we have no printed text for Didone from the 1641 premiere other than the Argomento e scenario, and indeed no printed libretto until the 1650 Neapolitan revival (see par. 14.4–5 above), some of the manipulations we find in the source printed in Naples could have occurred in between, on the occasion of some other unknown Feboarmonico revival. During that nine-year gap, a number of modifications could have taken place and consequently been inherited by the Neapolitan libretto.

16. Conclusions: Methodological and Historiographic Results