The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 27 (2021) No. 2

Madre d’Amore:

Redemptive Motherhood in Barbara Strozzi’s Sacri musicali affetti (1655)

Sara Pecknold*

Abstract

In 1655 Barbara Strozzi issued the Sacri musicali affetti, a print comprising fourteen passionately religious Latin motets. Strozzi may have composed these works in order to signify her transformation from the eroticized persona of her youth to a devout mother of consecrated, virginal daughters. Crucial to this transformation are the print’s dedication to Anna de’ Medici, Archduchess of Tirol, and the contents’ emphasis upon sanctoral motherhood as exemplified in Saint Anne, the mother of the Blessed Virgin Mary, as well as resonances with contemporaneous hagiography and the circumstances of Strozzi’s own life.

2. Le bellezze d’una Venere: Courtesans, Mothers, and Strozzi among the Unisoni

3. The Mother of Love and Giulio’s Poems for Strozzi’s First Opus

4. Earthly and Heavenly Patronesses: Anna de’ Medici and Saint Anne

5. Femmina super femminas: Strozzi’s Motets for Saint Anne and the Birth of Mary

6. “On lightest leaves do I fly”: The Joy of Ascent

1. Introduction

Why, oh my Heart, … do you crawl so timidly to her, to whom these pages have been consecrated? I understand you because, being within me, you cannot hide your feelings from me. You were at other times invited, and that hand, which was your gateway to the path [of virtue], assured you of your ascent; still, now you are no less cautious, even if you see that the foot that guides you on a solid basis does not waver. But which reproaches do I hear from you? You say to me: “Should one not consider those reasons for which a straight highway frees up a path to virtue?” … Since feminine weaknesses restrain me no more than any indulgence of my sex impels me, on lightest leaves do I fly, in devotion, to bow before you.[1]

1.1 These lines appear in the dedication of the Sacri musicali affetti (1655), the only sacred opus of the prolific seventeenth-century Venetian composer Barbara Strozzi (1619–1677).[2] Scored for solo voice and basso continuo, the fourteen Latin motets of Strozzi’s fifth opus praise a highly diverse group of saints, including Saint Anne (the mother of Mary), Saint Peter the Apostle, Saint Benedict, Saint Jerome, and Saint Anthony of Padua. The print also features music for the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Most Holy Sacrament, and the Most Holy Name of God. Despite its unique content, the Sacri musicali affetti has received scant scholarly attention. This is largely due to the fact that Strozzi’s fifth opus is an anomalous volume within the oeuvre of a decidedly secular composer, whose other prints comprise Italian madrigals and chamber cantatas, including some of a highly erotic nature.[3] Scholars have been puzzled but reluctant to ask the question: why, in the midst of a successful career as a secular composer, did Barbara Strozzi issue the Sacri musicali affetti? And furthermore, how does this opus signify an “ascent” and a “path to virtue,” as the composer herself claims in the dedication to Anna de’ Medici, archduchess of Innsbruck, quoted above? In this article, I hope to demonstrate that in order to answer these questions, we need to more fully understand Barbara Strozzi both as a woman of ambiguous morality and as a seventeenth-century Venetian Catholic who sought expiation and redemption, as expressed in the keen religious sentiments of her fifth opus.

1.2 The scholarly conversations concerning Strozzi’s fifth opus have been complicated by the reception of Barbara Strozzi as a woman of questionable morality, due partially to her status as the adopted daughter—and most likely the illegitimate offspring—of the libertine academician, poet, and librettist Giulio Strozzi (1583–1652). Scholars have also generally accepted that Barbara Strozzi was a courtesan—a hypothesis that was first advanced by David and Ellen Rosand in their assessment of Strozzi’s somewhat immodest portrait, painted by Bernardo Strozzi (no relation) around the year 1637 (Figure 1).[4] Robert Kendrick, however, has challenged this hypothesis, focusing principally on references in Strozzi’s sacred music to redemptive motherhood. Kendrick suggests that we may reinterpret Strozzi’s portrait, in which she poses with her left breast exposed, as alluding to early modern iconography of caritas, that is, Christian love embodied as a nursing mother.[5] Kendrick’s interpretation thus performs a redemptive reading of Strozzi’s body, in which feminine physiology is no longer eroticized; rather, the physical components of maternity become the loci of spiritual succor and, ultimately, salvation.

1.3 While Kendrick convincingly identifies sanctified, maternal love as the central element of the Sacri musicali affetti, we should not be too quick to dismiss the very convincing possibility that Strozzi was indeed a cortegiana onesta—a type of high-class prostitute, well-educated in the rhetorical and musical arts, and cultivated to serve as a suitable mistress to noblemen and their associates.[6] In fact, Strozzi’s sacred music can be understood only in light of her contemporaries’ perception of her as an object of amorous desire, fashioned in the likeness of Venus, the mother of erotic love. In other words, although motherhood is a crucial aspect of both the publicity surrounding Strozzi’s early career (including her portrait) and the Sacri musicali affetti, there are two distinctly different types of motherhood on display: the carnal and the spiritual, the illicit and the pure, the earthly and the heavenly.

1.4 These opposing models of motherhood seem to have come into conflict in Barbara Strozzi’s own life in the years surrounding the publication of the Sacri musicali affetti, as the young composer bore four illegitimate children by the married nobleman Giovanni Paolo Vidman. She eventually sent two of these children, her daughters Laura and Isabella, to the convent of San Sepolcro (in 1656, the year after the publication of her fifth opus).[7] This event, i.e., Strozzi’s gift of her daughters to the Church, may indeed have been the motivating force behind the composition and publication of the Sacri musicali affetti. In this essay, I argue that this opus—and in particular Strozzi’s motets concerning the birth of the Blessed Virgin Mary—signify the composer’s supplication for transformation from the immoral muse of her father’s literary academy (a muse fashioned in the likeness of Venus) to a devout mother of consecrated, virginal daughters (a mother formed in the virtues possessed by Saint Anne). I have divided this essay into two parts. First (Chapters 2–3), I discuss contemporaneous writings that liken Barbara Strozzi to Venus, often by utilizing tropes that were applied to early modern courtesans. In the second section (Chapters 4–6), I explore the significance of Strozzi’s motets about the birth of Mary, side by side with early modern writings that depict Saint Anne as an exemplar of virtuous motherhood. When placed in conversation with one another, these sources reveal that at the heart of the Sacri musicali affetti lie the themes of contrition, supplication, transformation, and redemption—the means by which the composer will accomplish the fulfillment of her professed desire for “ascent.”

2. Le bellezze d’una Venere: Courtesans, Mothers, and Strozzi among the Unisoni

2.1 A common early modern belief posited that the bodily senses exerted considerable power in the formation of virtue or vice.[8] While the contemplation of all things holy could prepare the soul for heaven, conversely, the penetration of the senses by lascivious art or other maliferous influences could corrupt the soul. Sight is foremost among the senses named as powerful spiritual influences: whereas looking upon religious objects and the Blessed Sacrament had sanctifying effects, the amorous meeting of the gaze was deleterious to the soul, as it was tantamount to a declaration of sexual availability. This belief is articulated clearly in the writings of the Venetian poet and nobleman Giovan Francesco Loredano, founder of the notoriously libertine literary society, the Accademia degli Incogniti.[9] In his Bizzarrie academiche (“Learned Eccentricities”), Loredano claims:

The greatest glory of beauty is to be the object of all eyes and the soul of every heart. If beauty has not this cortège of every soul, … it is poor in merit and in power. But if beauty is chaste, how much does it lose its merit, how much does it forfeit all regard, how much does it lose its virtues, how much does it forfeit its lovers. It is found only in the Idea of Plato, that lovers can love without an unchaste purpose. Thus, chastity condemns beauty, because she takes away a multitude of followers and an infinity of adorers.

The eyes are the perfection of the face’s beauty for this reason: because they are all light. And for no other reason are they located beneath the arches of the eyebrows, to show us [this perfection], bringing us the triumphs of beauty. Chastity, on meeting [the lover’s gaze], lowers her eyes.… [And] behold, this is how chastity takes away the greatest ornament of beauty; and with reason one can say that beauty is dead at the moment when the gaze is lost.[10]

Here Loredano has imparted an impossible conundrum to the beautiful—yet modest—woman, who must forfeit her beauty in order to safeguard her virtue. The converse scenario may be seen in Barbara Strozzi’s portrait, in which, as the Rosands have explained, Strozzi certainly did not eliminate her beauty by lowering her gaze; rather, her “glance … directly engages us, her viewers.”[11]

2.2 While the courtesan could use meeting the amorous gaze as a powerful aphrodisiac, the penetration of the lover’s ears by her singing voice was considered even more perilous, due to its invisible nature. As such scholars as Wendy F. Heller and Bonnie Gordon have shown, these aural associations carried special weight for courtesans’ musical performances.[12] In fact, early moderns—influenced by the ancient medical writings of Soranus and Avicenna—believed there to be an objective, biological connection between a woman’s singing mechanism and her reproductive organs. Some writers went so far as to link the various parts of a woman’s sexual anatomy to that of the voice, bit by bit and part for part.[13] This was especially important in regard to the courtesan, who nearly always offered virtuosic musical performance as an element of her bouquet of sensual delicacies. Caution was advised in beholding the woman’s mouth as she sang, and, above all, in the perception of the courtesan’s voice through the vulnerable portals of the ears. Many polemicists warned readers of the perfidious nature of the courtesan’s song. For example, in his anti-courtesan satire, La retorica delle puttane, Ferrante Pallavicino remarks:

She persists in moving the affections, on the one hand by penetrating (by her powers) the ears, ravishing them, and on the other by creeping in [through] the eyes. To that end, the puttana also uses this bodily eloquence, artificially employing the tongue and the movements of the limbs. She assists the efficacy of her persuasiveness with a sonorous and variable voice, according to the doctrines of music, being that song above all is the most singular enticement to love.[14]

2.3 The courtesan’s trade carried harmful effects beyond the dyad of the cortegiana and her current paramour. Not surprisingly, many courtesans had illegitimate daughters. Due to the restrictive Venetian dowry system, when these daughters came of age, they had few viable options; the two most common paths were religious life and courtesanship.[15] Indeed, many courtesans trained their daughters in the same profession—a practice that inspired such biting satirical writings as Pietro Aretino’s dialogues, in which an established courtesan schools her daughter in the tricks of the trade.[16] By the late sixteenth century, this practice had become pervasive enough to prompt prohibitive legislation: mothers who prostituted their daughters were sentenced to stand on a platform in the Piazza San Marco, as their crime was proclaimed aloud; these women were subsequently banished for two years. Men who committed the same crime were sentenced to two years’ service at the galley oars.[17] And, lest anyone should entertain the idea that courtesans themselves were able to enjoy a kind of liberated “sexual autonomy,” we can consider the famous letter of the wealthy and greatly admired sixteenth-century courtesan Veronica Franco, in which she implores a fellow cortegiana not to condemn her daughter to a life of prostitution:

You know how many times I have begged and warned you to protect her virginity; [however, where] once you made her appear simply clothed and with her hair arranged in a style suitable for a chaste girl, with veils covering her breasts and other signs of modesty, suddenly you encouraged her to be vain.… You let her show up with curls dangling around her brow … with bare breasts spilling out of her dress … and every other embellishment people use to make their merchandise measure up to the competition…. [Courtesanship] is a most wretched thing, contrary to human reason, to subject one’s body and labor to a slavery terrifying even to think of. To make oneself prey to so many men, at the risk of being stripped, robbed … along with so many dangers of injury and dreadful contagious diseases; to eat with another’s mouth, sleep with another’s eyes, move according to another’s will, obviously rushing toward the shipwreck of your mind and body.… And if to worldly concerns you add those of the soul, what greater doom and certainty of damnation could there be? … In matters crucial to life on earth and to the soul’s salvation, don’t follow examples set by others.[18]

Clearly, for Veronica Franco (and, we may assume, for many less fortunate cortegiane) the courtesan’s life was one of sexual slavery, a miserable state to which a mother should never condemn her own daughters.

2.4 These phenomena illuminate several unexamined passages found in seventeenth-century writings about Barbara Strozzi, who was the illegitimate daughter of Giulio Strozzi’s “longtime-servant and heir-designate” Isabella Garzoni.[19] Giulio promptly adopted Barbara after her birth in August of 1619. He provided for her excellent education, which included music lessons with the illustrious Francesco Cavalli.[20] By her early teens, Barbara was performing music for visitors to the Strozzi home; some of these performances are praised in writings by Giulio’s literary associates, as well as Giulio himself.[21] Like Loredano, Giulio Strozzi was a member of the Accademia degli Incogniti, and in 1637, Giulio founded the Incogniti’s musical sub-academy, the Accademia degli Unisoni, as a vehicle for the display of Barbara’s musical talents.[22] Rosand’s explanation of Barbara Strozzi’s role at Unisoni meetings (which occurred in the Strozzis’ home) is well known: Barbara “functioned as mistress of ceremonies, suggesting the subjects on which the members were to display their forensic ingenuity, judging the discourses, and awarding prizes to the best of them; she also performed songs during the course of the meetings.”[23] Drawing upon the Unisoni’s published minutes (the Veglie de’ Signori Unisoni) as well as a series of satires issued against the Unisoni in 1637, Rosand has demonstrated how Barbara Strozzi’s role in the academy was understood to be one of a highly sexualized nature.[24]

2.5 Yet several of the most revealing passages of the Veglie have never been brought to light. These include the prefatory content of the first Veglia, which was dedicated to Barbara. The dedication is marked by sensuality and sexual resonances:

Most Illustrious Signora.

You have the largest part in the glories of this new academy. The fruits that it collects are due to none other than you. It is usual to dedicate every object to the deity from whose benevolent influences it flows; therefore, I feel obliged to donate the first fruits of this tree, grafted with gifts, to you, who are the first sphere in these heavens. Indeed, the harmony of your voice makes it so, whence one can reasonably imagine this place to be an earthly paradise, in which our gaze enjoys the contemplation of all beauties, and the ear enjoys the excellence of your singing. Thus, the merits of your Ladyship will be borne out by these pages, penned with inks that function as shadows to the colors of your virtue. Because they have your name on the title page, they assuredly will spread the admiration of your values to every heart capable of appreciating the beauties of a Venus, or the melody of an angel. I would say more if your modesty did not blush at these concepts. May Our Lord preserve you as an ornament of this age, while I admire you as the Phoenix of our day.[25]

Several phrases undoubtedly captured the attention of the seventeenth-century reader. When the author boasts of his amorous delight in beholding Barbara’s beauty, he leaves open the possibility that she returns his gaze, offering an entrée to sexual access. When he praises the delight of Barbara’s harmonious singing, he refers to the courtesan’s most destructive attribute: her voice. Perhaps most significant is the likening of her beauty to that of Venus, whose image also served as an icon for la Serenissima—the Serene Republic of Venice—as well as for courtesans and mothers of children begotten in commercial sexual exploits.[26]

2.6 The most suggestive content is found in an aria that Barbara sang, Dite, amanti, as recounted in the Veglia seconda: “Tell, lovers, what beautiful fruit your flowers produce.…” See Text 1. The most provocative phrase appears in the refrain: “horti di Cupido” (Cupid’s gardens). John Florio’s Italian-English dictionary of 1611 defines the phrase “horti di Venere” (gardens of Venus) as “women’s quaints.”[27] It seems that in Barbara’s song, the poet replaced the conclusion of the euphemism “horti di Venere” with “di Cupido”—not a far stretch, to say the least.[28] Thus, the performance of Dite, amanti—especially when considered alongside the dedication of the Veglia prima—reveals that the Unisoni (under the sponsorship of the composer’s father) were keen to make public not only Barbara’s beauty and her musical talents, but also her eroticized objectification as a new Venus.

3. The Mother of Love and Giulio’s Poems for Strozzi’s First Opus

3.1 In addition to the writings of the Unisoni, the poems that Giulio Strozzi provided for his daughter’s first opus (Il primo libro de’ madrigali …, 1644) suggest that he continued to cultivate a courtesan-like persona for his daughter, which she did not reject as she embarked on her career as a published composer.[29] This is especially evident in the print’s multiple invocations of the human body. Consider, for instance, Le tre Grazie a Venere, a three-voice madrigal in which the Graces chide Venus for partially concealing herself (Text 2).[30] The first lines of Giulio’s poem are telling: “Beautiful mother of Love,” the Graces intone, “do you not remember how, naked … you won [the prize of Paris]?” Flummoxed that she should wish to cover her “beautiful limbs,” the Graces urge Venus to throw away her “ornaments, her mantles, and her veils.” Eventually, however, the poet is bound to concede that the partially concealed body can inflame the lover more than the wholly visible one. The poem’s conclusion evokes Barbara’s portrait, in which the composer’s body is partially clothed—and thus partially revealed.

3.2 As Anna Aurigi has explained, such poems as these, replete with erotic content and double entendres, were very much the fashion of the day, and it was not at all unusual for aristocrats renowned for their religious devotion (such as Vittoria della Rovere, the dedicatee of Strozzi’s first opus) to enjoy highly sensual musical fare.[31] At the same time, Aurigi acknowledges that Giulio Strozzi’s academic activities seem to have been not only libertine but somewhat “transgressive.”[32] Furthermore, while it is entirely possible that Barbara Strozzi herself may have disapproved of the lascivious content of her father’s verses and the sensuous praise she garnered from his fellow literati, it is paramount to acknowledge that during the first decade of her career—and in particular at the time when her portrait was painted—Barbara Strozzi was understood by her contemporaries to be a living icon of Venus, the mother of Eros. It is these undeniable, early associations that underline the significance of the content of the Sacri musicali affetti.

4. Earthly and Heavenly Patronesses: Anna de’ Medici and Saint Anne

4.1 Strozzi’s first gesture of transformation—as expressed in her fifth opus, the Sacri musicali affetti —is the replacement of the eroticized mother of Cupid with a devout mother of a consecrated, female offspring: namely, Saint Anne—the Mother of the Blessed Virgin Mary—who is praised in the first motet of the print, Mater Anna. The prominent placement of Mater Anna reflects Saint Anne’s importance as the heavenly patroness of Strozzi’s dedicatee, Anna de’ Medici, Archduchess of Innsbruck (1616–1676).[33] A few biographical details will help us grasp the significance of this dedication, especially regarding the importance of virtuous motherhood. Anna’s father, Grand Duke Cosimo II (1590–1621), died when she was about five years old; the Tuscan princess then lived under the regency of her mother, Grand Duchess Maria Maddalena (1589–1631), who famously commissioned the first opera composed by a woman, Francesca Caccini’s La liberazione di Ruggiero.[34] Throughout her childhood, Anna attended the Florentine court’s musical-theatrical spectacles on Biblical and hagiographical topics, often featuring strong, virtuous women protagonists.[35] In 1646, Anna de’ Medici married Archduke Ferdinand Karl of Tirol, a great patron of some of the finest musicians of the day, including composer and singer Antonio Cesti.[36] In the first ten years of their marriage, Ferdinand Karl and Anna engaged in many public displays of Catholic religious devotion, most of which included musical performances.[37] During this time, they also struggled to conceive a male heir: by 1655, Anna had given birth to one daughter, she had tragically endured a still birth (or the death of an infant shortly after delivery), and she was again pregnant.[38] A Florentine castrato resident in Innsbruck, Atto Melani, reported that during her childbearing confinement, the archduchess requested serenades (possibly motets to favorite saints) by various star singers of the court.[39] All of these phenomena—her childhood formation, her well-known religious devotion, her access to virtuoso musicians in her husband’s employ, and her reliance upon musical comfort during her perinatal ordeals—reveal Anna de’ Medici to have been an ideal recipient of the Sacri musicali affetti.

4.2 And indeed, for Strozzi—as for most seventeenth-century Catholics—Anna de Medici’s patroness saint was a familiar figure, appearing in myriad devotional writings as a paragon of feminine virtue and as a mother wholly invested in her daughter’s consecration to the service of God.[40] Whereas Venus, sometimes in the guise of the prostitute, spawns Cupid, the harbinger of illicit exploits, Saint Anne brings forth from her saintly body Mary, the portal of salvation. Several early modern writings describe Anne’s qualities by which she is the fitting recipient for God’s work in the Immaculate Conception. For instance, in Lucrezia Marinella’s vita of the Blessed Virgin Mary (1602, rev. 1604), the author praises Saints Anne and Joachim (Mary’s father) thus:

Obstinate wrath never disturbed their gentle breasts … nor did they allow themselves to be carried away by frenzied appetite … which seduces the pliant senses with worldly lasciviousness…. Their pure modesty was a model for others as to how to moderate their own desires, and therefore these others became chaste and holy through looking at them…. They lived together with calm souls, the world’s praise, and God’s gifts, with such a flame of charity, with so much strength in their religious beliefs, and with such a zealous faith that they enjoyed in a certain way down here on earth what is enjoyed to perfections in Heaven.[41]

Saint Anne’s virtues, therefore—especially her resistance to the “frenzied appetite … which seduces the pliant senses with worldly lasciviousness”—form the perfect foil for the license of Venus, which seduces men to indulge the inordinate and excessive passions of the flesh.

5. Femmina super femminas: Strozzi’s Motets for Saint Anne and the Birth of Mary

5.1 With Marinella’s praise of Saint Anne’s attributes ringing in our ears (or our minds, as the case may be), we are better equipped to investigate the content—both textual and musical—of the first motet of Strozzi’s fifth opus, Mater Anna (“Mother Anne”). Although the individual who compiled the texts of the Sacri musicali affetti is unknown, the poet seems to have owned a breviary and perhaps a missal, as all of the texts are in some way derived from the liturgy.[42] Robert Kendrick has demonstrated that the text of Mater Anna is a paraphrase of Saint John Damascene’s sermon read at Matins on the feast of Saint Anne.[43] Paramount to our discussion is the way in which—following the liturgical exemplar—the text of Strozzi’s motet praises the physical components of maternity as symbols of theological import: see Text 3 and Table 1.[44] For example, Anne’s womb becomes a temple within which “God has built an altar of sanctification [Mary],” Anne’s body brings forth “a meadow formed by the Divine beyond nature,” and many times she is likened to a tree or a plant that bears “the fruit of blessing” whom she “nourished … with [her] breasts.”

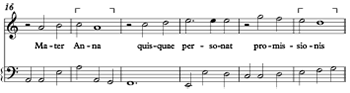

5.2 When she set this text to music, Strozzi bolstered the impact of the text’s repeated invocations of maternal physiology and the act of parturition in a variety of ways. For instance, the motet opens with a dulcet, lilting, triple-meter refrain, which is repeated twice thereafter in alternation with duple-meter, recitative-like sections. The refrain features a distinctive hemiola enacted through syncopation; see Example 1.

The somewhat jarring nature of the hemiola distinguishes it from the regularly undulating material of the rest of the refrain—and in every occurrence, this syncopated figure is used to set statements about giving birth, i.e., “promissionis foetum peperit” (gave birth to the offspring of promise), and “Jesus prodiit” ([which] brought forth Jesus). Strozzi also draws attention to the maternal body in the duple-meter sections by setting crucial words to stunning, extensive, virtuosic passaggi, including “fabricavit” (referring to God’s creation of Mary in Anne’s sanctified womb), “miraculum” (referring to Anne’s miraculous pregnancy—tradition holds that she was sterile), and “peperi” (in speaking of the divine seed that issued from Anne’s womb, i.e., Jesus as the offspring of Mary); see Example 2.

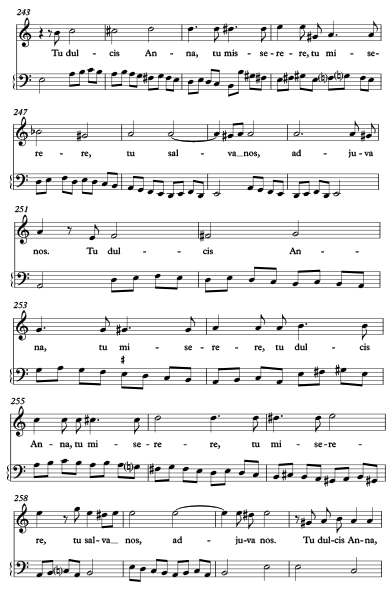

5.3 The unusual musical structure of Mater Anna also merits attention. The aforementioned refrain occurs at the beginning of the motet, and again after the first two duple-meter sections, but not after the third and final section. To the listener well-acquainted with seventeenth-century conventions, the lack of a final refrain is somewhat surprising. This absence of a closing refrain is preceded by a decisive change in affect that jolts the listener to attention, heightening expressive tension: whereas the first two duple-meter sections feature expostulations of joyful exuberance, the final passage pleads desperately for Saint Anne’s intercession: “you, sweet Anne, have mercy on us, save us, help us.” This obsecration is set to excruciating chromaticism, as the voice performs a harrowing ascent and weeping descent over the span of a tenth (from e′ to g″). The final cadence evokes the Phrygian mode, while the lack of a return to the triple-meter refrain lends the entire motet a somewhat truncated quality. See Example 3. Structurally—as well as melodically—the composer has incited anticipation, and she has left her listeners on a razor’s edge, as they uneasily await some sort of answer to these fervent supplications. The response seems to lie in Strozzi’s motet for the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Nascente Maria.

5.4 Scholars have failed to notice that Mater Anna forms a theological pair with Nascente Maria (Text 4). While the two motets are separated within the print (Mater Anna is the first motet, and Nascente Maria is the twelfth), the texts of both motets refer to the soteriological significance of Mary’s birth. Considered together, these two motets trace a trajectory from desperate supplication to triumphant joy, brought about by the birth of a holy female offspring.[45] Like Mater Anna, the text of Nascente Maria is also drawn from its associated feast; nearly every line bears resemblance to the Divine Office for the Nativity of the Virgin (see Table 2).[46] Nascente Maria also carries forth and broadens the theme of sanctoral femininity, by drawing the listener’s focus from Anne to Mary, and then ultimately to all women who join in Mary’s “yes” to God’s redemptive work. This becomes especially apparent if we consider two particular passages of the motet that address Mary as a new dawn, a new kind of woman, and a new exemplar for all of humanity.

5.5 The first passage under consideration concerns the traditional understanding of Mary’s birth as heralding a new, salvific day for humankind. In Marinella’s narrative, God responds to Anne’s pleas to bear a child by sending an angel who declares to her:

Great Lady, Lady of celebrated virtue, honor, and pride of little Nazareth, the One to whose power everyone bows down has sent me to reveal to you how will come forth from your most holy womb that fortunate tree.… Then the one who is the salvation of the incurable and inconsolable world will be born of you…. She will help and support the sick, the poor, and those falling into ruinous misfortune. Evil spirits will flee from the sound of her powerful words…. And thus the amazed world will consecrate chaste virgins to the glorious memory of the immortal Lady in wonder at her marvels…. Her name will be Mary, a marvelous name, meaning a star lighting the shadows of perpetual death.[47]

Mary’s nature is thus one of light, akin to that of the stars. This theme recurs in Marinella’s account of the Blessed Virgin’s birth, in which Mary is compared to Aurora, the goddess of the dawn:

Aurora, already appearing in the window to the East, let fall from her breast the most beautiful, fresh, and sweet roses she had ever gathered in the heavenly gardens, as Anna, gazing with her lovely eyes at the roads to Paradise, and absorbed with certain joy, worshiped the Lord.… And behold, the rose, brought forth with little pain by her mother Anna, peeps out from the maternal shell, fragrant in her fine features. Behold the blessed little Angel who, coming out of the holy womb, made the world worthy of itself. Behold the great Lady, a little baby girl who gazes at the world full of sorrow with the eyes of her merciful goodness.… The whole of her glorious body was a composition in ivory, which breathed, on which nature had sprinkled the rosiness of Aurora’s cheeks.[48]

Here, rather than the erotic gardens, the “horti di Cupido” of which Barbara Strozzi sang for the Unisoni, Mary’s birth brings to earth the “sweet roses” of the “heavenly gardens.” Here, rather than bearing Cupid, who incites disordered passions, Anne gives birth to a “blessed little Angel” who “makes the world worthy of itself,” and whose body is glorious, not for its sensual qualities, but for its immaculate purity.

5.6 It is useful to compare this pair of excerpts from Marinella with one of the most striking textual-musical moments in Strozzi’s motet:

| Strozzi, Nascente Maria | Marinella, La vita di Maria Vergine |

| Mary is born so that it may be the beginning of salvation.

Mary is born so that she may aid the fallen world. Mary is born so that there may be forgiveness of sins. Mary is born so that there may be the remedy of reconciliation. |

Then the one who is the salvation of the incurable and inconsolable world will be born of you…. She will help and support the sick, the poor, and those falling into ruinous misfortune. Evil spirits will flee from the sound of her powerful words.… The amazed world will consecrate chaste virgins to the glorious memory of the immortal Lady.… |

| When Mary is born, the Dawn [Aurora] of the Church rises, about to give birth to the pure sun of justice, with joy.

|

Aurora, already appearing in the window to the East, let fall from her breast the most beautiful, fresh, and sweet roses she had ever gathered in the heavenly gardens.… |

In Strozzi’s motet, this passage receives particularly lucid musical treatment; see Example 4.

Here, the music shifts abruptly from an exuberant, melismatic aria to calm, transparent recitative or quasi-recitative. Strozzi sets the words syllabically, repeating them at three different levels of transposition, as the music winds its way through the world of the hexachordal system.[49] The listener is enveloped in plain, declamatory statements about the cosmic fruits of the Virgin’s birth: salvation, aid, forgiveness, remedy, and reconciliation. Thus, the poet’s choices and Strozzi’s crystalline musical treatment thereof highlight the importance of consecrated virginity—in Mary herself as well as all future women in religious orders—within the narrative of salvation.

5.7 The penultimate section of the motet also merits our attention, as it extends the theme of redemptive femininity to include all women. Here, the singer exults, “O femmina super femminas” (O woman above all women). Curiously, in the 1655 print, the word “femmina” (woman) has been given the Italian rather than the Latin spelling, “femina.” It is possible that this is due to a printing error, especially since (as Wendy Heller has shown) many seventeenth-century sources spell the word “femina”—even in Italian—with one “m.”[50] However, given the various words used to describe women in the late Renaissance, this nuance is still somewhat puzzling. As William F. Prizer noted in his work on the sixteenth-century frottola source Antinori 158, different words for women denoted a hierarchy of virtue:

[The scribe of Antinori 158, Domenico di Benedetto, uses] three discrete words for “woman” …: donna, dama, and femmina.… Dama seems to be a more elevated and courtly word, the equivalent of “lady” or “madonna.” … Femmina, on the other hand, is a less complimentary word. Sir John Florio, in his late sixteenth-century dictionary, defines femmina as “a women, a wife, sometimes taken for a bad light woman.” The word was also adopted in Florence itself for prostitutes.[51]

With these associations in mind, the extent to which Strozzi’s music magnifies the notion of “femmina” is remarkable. By naming Mary “femmina,” the text gathers together all women, including those of ill repute, and places them all under the Blessed Mother’s mantle. Strozzi’s musical choices augment this gesture: the rhythmic acceleration, the echoing phrases, and the sustained note in the voice over the ciaconna bass line depict angelic exultation and a raucous party all at once; see the two excerpts in Example 5. Music and text together simultaneously overwhelm the listener with the solemnity and the jubilation encoded within this birth-event. For Strozzi and her poet, the birth of Mary offers a typological reading for the potentially redemptive nature of all motherhood and the birth of all daughters.

5.8 The importance of consecrated daughters must have been foremost in Strozzi’s mind during the first half of the 1650s, as (we can assume) she composed the Sacri musicali affetti. The decade surrounding the publication of her fifth opus was replete with momentous events: in May of 1648, Giovanni Paolo Vidman—Strozzi’s lover and the father of at least three of her children—died; Giulio Strozzi also died on 31 March 1652; and in 1653, Barbara’s mother died as well.[52] Strozzi’s fifth opus was printed and sent to Anna de’ Medici at least by April of 1655;[53] and in July of 1656, Barbara’s two daughters, Laura and Isabella, entered the convent of San Sepolcro. As Beth Glixon has shown, in a fascinating twist of exceptional irony, Barbara Strozzi was able to place her daughters in San Sepolcro only due to her extramarital liaison with her daughters’ father. This is because, as Glixon explains, the dowry required for Laura and Isabella to enter San Sepolcro was actually paid by Giovanni Paolo Vidman’s widow, Camilla Grotta Vidman. Strozzi’s daughters entered San Sepolcro in early July 1656; their entry cost a “spiritual dowry” of 2,000 ducats.[54] Glixon remarks that although neither Barbara Strozzi nor her children are named in Vidman’s will, the document refers to a “sealed codicil” inserted therein, the contents of which were to be “‘punctually, secretly, and faithfully executed.’”[55] Glixon suggests that the codicil may have contained information about dowries Vidman had set aside for his illegitimate daughters. Although insufficient for marriage—or even to situate Laura and Isabella in one of the wealthier Venetian convents—the funds were enough for entrance into the mendicant convent of San Sepolcro.[56] That San Sepolcro had family connections (Camilla Grotta Vidman was related to the abbess) made it the convenient and obvious choice.

5.9 Therefore, in Barbara Strozzi we see an illegitimately born courtesan who found herself at a crossroads when her own daughters approached puberty: how would her daughters survive when she could no longer support them? Would she follow her father’s example and have Laura and Isabella trained to operate in the literary circles that were the cortegiana onesta’s conquered territory? No, she would not; instead, Barbara Strozzi—possibly encouraged by her late lover’s will—chose a different path, thus breaking a cycle that was all too familiar in early modern Venice, where illegitimate daughters became courtesans, giving birth to illegitimate daughters who were also forced to become courtesans. Instead, in the Sacri musicali affetti, the new Venus is transformed into a humble and pious mother, whose submission to God’s will opens a path to Heaven.

6. “On lightest leaves do I fly”: The Joy of Ascent

6.1 The remaining motets of the Sacri musicali affetti explore the themes of contrition, supplication, transformation, and redemption. These works are addressed to Saint Peter the Apostle, the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Most Holy Sacrament, and the Most Holy Name of God, as well as Saints Benedict, Jerome, and Anthony of Padua. The motets for Saint Peter recount his attempt to walk to Jesus on the water (In medio maris; Matthew 14:24–33), and his miraculous liberation from prison by an angel (Erat Petrus; Acts 12:6–23). In both cases, Saint Peter requires supernatural intervention in order to participate in God’s work: in the first instance, the hand of Christ rescues him from the waves of the sea; and in the second, the angel of God frees him from the chains of his imprisonment. The penultimate section of Erat Petrus is particularly supplicative. Here, the recitative-like paraphrase of the narrative from Acts is interrupted by a lyrical, triple-meter section entreating Saint Peter to exercise his apostolic authority, i.e., to absolve the sins of his people—a point well in keeping with the Tridentine emphasis upon the frequent use of the sacraments of Confession and Communion. The motets to the Blessed Virgin Mary feature similar supplicatory sections, in which the Virgin’s intercession is implored in winding chromatic lines akin to the final section of Mater Anna. The motets to the Blessed Sacrament are masterpieces of Eucharistic musical adoration, extolling the sweet abundance of grace conferred in the salvific meal, alongside plaintive appeals to God’s mercy as administered in this most holy of banquets. Strozzi’s motet to the Most Holy Name of God, Oleum effusum, may have been intended as a votive musical offering for her deceased father’s soul, i.e., it may be connected to Giulio Strozzi’s request to be buried in the Dominican church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo, which housed the Venetian confraternity dedicated to the Most Holy Name of God.[57] The motets to Saints Benedict, Jerome, and Anthony of Padua feature meditations upon the human voice as an agent of conversion and the act of singing on earth as the prefiguration of participation in angelic exultation.

6.2 The question remains whether the gesture of transformation described herein extends beyond the pages of Strozzi’s fifth opus, that is, to the life of the composer herself. We do know that after the publication of the Sacri musicali affetti, Strozzi certainly continued composing, publishing, and fostering her relationships with such patrons as the Duke of Mantua.[58] At the same time, she had no more children after the death of her noble paramour, Giovanni Paolo Vidman. Furthermore, like her father before her and most of her Venetian contemporaries, she must have solicited the grace imparted through the sacrament of penance.[59] As Glixon has shown, Barbara Strozzi died in Padua twenty-two years after the publication of the Sacri musicali affetti, at the age of 58. Due to Glixon’s research, we also know that Barbara Strozzi died in the midst of receiving final rites, and in fact, immediately after she had received final absolution and before receiving Viaticum.[60] I have suggested elsewhere that Strozzi traveled to Padua in 1677, ill and aged beyond her years, in order to make a pilgrimage to Saint Anthony’s tomb and to receive the indulgence conferred upon the faithful who completed this journey on his feast day. If so, then the redemption of Barbara Strozzi’s very person—body and soul—was indeed accomplished at the end of her spectacular musical life.

Acknowledgments

The research for this essay was made possible in part by generous grants from the Cosmos Club of Washington, D.C., and the American Musicological Society. I am also grateful to Anthony DelDonna, Francesco Cotticelli, Ellen Rosand, Beth L. Glixon, Jonathan Glixon, and Andrew H. Weaver for their immeasurable help and advice, and to Anthony DelDonna and Ellen Rosand for patiently reading and improving earlier versions of the paper.

Examples

Example 1. Mater Anna, excerpt from first refrain

Example 2. Mater Anna, three passaggi in the first duple-meter section:

a. “fabricavit”; b. “miraculum”; c. “peperi”

Example 3. Mater Anna, final passage

Example 4. Nascente Maria, “Nascitur Maria”

Example 5. Nascente Maria, two excerpts from the penultimate section:

a. “O femmina super femminas”; b. “O gloria”

Figures

Figure 1. Bernardo Strozzi, Gamba Player (portrait of Barbara Strozzi, ca. 1637). Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden.

Tables

Table 1. Mater Anna, liturgical intertextuality with the Feast of Saint Anne: Matins, Lessons IV, V, and VI

Table 2. Nascente Maria, intertextuality with the Office of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Texts

Text 1. Dite, amanti. Veglia seconda de’ Signori Academici Unisoni havuta in Venetia in casa del Giulio Strozzi.

Text 2. Giulio Strozzi, Le tre grazie a Venere. Barbara Strozzi, Il primo libro de’ madrigali.

Text 3. Mater Anna. Barbara Strozzi, Sacri musicali affetti.

Text 4. Nascente Maria. Barbara Strozzi, Sacri musicali affetti.