The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 27 (2021) No. 1

Notating—Accompanying—Conducting:

Intabulation Usage in the Levoča Manuscripts

Jeffery T. Kite-Powell*

Abstract

Seventeenth-century organists of the Zips region (then in Royal Hungary, now in Slovakia) relied on German letter notation to intabulate works for practical use. Manuscripts in the Library of the German Evangelical Church in Levoča show that organists played works by internationally known, contemporary composers, that they composed new works, and that churches had the personnel to mount large-scale, Venetian-style polychoral performances. The manuscripts further show that, although organists had the know-how to play from a thoroughbass line or a reduced set of parts, they apparently preferred to play—and direct—from intabulations that served as conductors’ scores.

2. Cantors and Organists, Composers and Dates

3. The Aspect of Tablature Notation

5. The Aspect of Basso continuo

6. The Use of the Figured Bass

7. The Aspect of the Conductor’s Score

8. Performance Settings and Conditions

10. Rare Instructions in Organ Tablatures

11. “Blocked” and “Stacked” Format

1. Introduction

1.1 The purpose of this article[1] is to take up Cleveland Johnson’s plea found at the conclusion of the chapter on “The Purpose and Use of Intabulations” in his book Vocal Compositions in German Organ Tablatures 1550–1650: “Finally, a plea is due for the dozens of tablature sources catalogued in this work. Each volume is a fascinating microcosm of the immediate musical surroundings in which it was compiled and deserves a detailed study of its own.”[2] In the course of this study, references to the many points he discusses will be made and new ideas will be presented, all of which will be illustrated by examples found in organ manuscripts located in the Library of the German Evangelical Church in Levoča, Slovakia (SK-Le). MSS 13990a, 13990b, and 13993 are cataloged in Johnson’s work; MSS 13991, 13992, and 13994 are not.[3]

1.2 Levoča is located in the northeastern part of Slovakia known in German as the Zips region (Spiš in Slovak). Beginning in the fifteenth century, Germans from central Europe—Saxony, Thuringia, Silesia, Transylvania, among others—began migrating to the area, and by the early seventeenth century, the Zips region had become a highly developed center of music and the fine arts with Levoča as the principal city. As Jena Kalinayová-Bartová has noted, “The Spiš (Zips) … regions … belonged to the most economically developed areas of Royal Hungary. These regions were dominated by a German-speaking population concentrated in towns where music productions were organized under the patronage of local municipal patricians.”[4] The following account attests to the sophisticated lifestyle of well-to-do residents at the time:

According to a contemporary chronicler from 25 February 1626, a troupe of eight trumpeters, elegantly clad in red, with silver trumpets, rode into Levoča in front of a wagon carrying Katharina von Brandenburg, second wife of Gabriel Bethlen.[5]

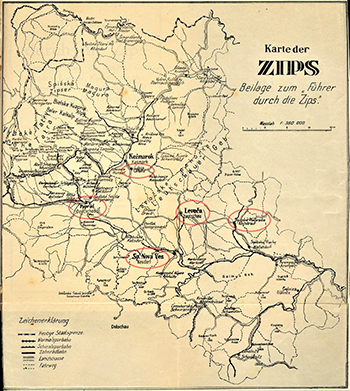

The Lutheran oriented Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession became the principal religion, and high-quality music, patterned on that of the German districts in the area, came to be an important part of church life, largely supported by the area’s wealthy residents. The map in Figure 1 will acquaint the reader with the region. Shown are the distances to Levoča of the nearby cities that may have contributed performers when large-scale works were performed.

1.3 There has been a great deal of research on the organ tablature books in the past two decades, led by Marta Hulková and her disciples, that has unearthed details concerning the origins of the manuscripts, the composers and copyists, the cultural settings that provided for large-scale performances in the local churches in Levoča and nearby cities, and more.[6] Hulková provides this assessment of the provenance of the Levoča tablatures:

The question of the place of origin of musical manuscripts … in the local environment has not been definitely solved yet. Based on contemporaneous notes and, at certain instances, on ducti, we can deduce that these manuscripts might have belonged to church communities in the territory of historical Hungary at the end of the 16th and in the first half of the 17th century. Therefore, we assume that this [music] might have been performed at this period in the local environment in Catholic (Franciscan) as well as Evangelical churches.[7]

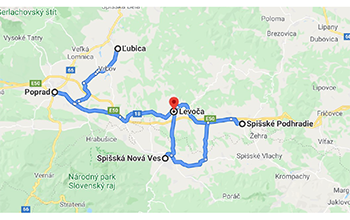

According to Hulková, the original printed editions (typically sets of vocal/instrumental partbooks) from which the compositions were intabulated are still in the Library of the Protestant Rectory. However, while certain alterations in the Levoča exemplars of the printed vocal sources (which are not found in duplicate exemplars elsewhere) correlate exactly with the organ tablature, “it is not exactly known where the musical prints were kept at the time when the tablature books were prepared nor when they were placed in the Library of the Evangelical Church in Leutschau”; nor can contemporaneous manuscripts of music be “claimed unequivocally” as sources for the tablature books.[8] In any case, the Leutschau/Lőcse/Levoča Music Collection in SK-Le does hold copies of the vocal music performed during this period, and (as we shall see below) several of the works in the tablature books were copied in the city of L’ubica (Leibnitz in German), just 25 km from Levoča. Figure 2 shows a current map of the principal cities that figure into the history of the six Levoča tablature books.

1.4 In considering more generally how the organists came into possession of the music they transcribed, Hulková describes the transmission of music throughout the region thusly:

The findings of research allow the conclusion that, besides Saxony and the territory of the present-day Saxony-Anhalt where the majority of the printed sources came from, the tablature books also reveal close connections and possible correspondences [concordances] with the Silesian music-cultural environment. At the time, Silesia was a crossroads for the exchange of cultural values for the German-speaking population of Central Europe. Occasionally, contemporaneous musical repertoire handed down in manuscripts was supplemented thanks to the migration of organists in Central Europe, whether from Bohemia and Moravia, Transylvania, or from the Baltic towns belonging to Prussia. From other musical centers of Europe, for instance Italy, a rich digest of works was presented in the collective prints of the time. The scribes (organists) of the tablature books preserved in Zips were attracted in this regard mainly by anthologies compiled by A. Schadaeus (1611, 1612, 1613) and E. Bodenschatz (1603).[9]

1.5 The approximately 1100 compositions in the six tablature books that make up the collection are written in new German organ tablature (NGOT), the standard notational system employed by all organists of German-speaking territories from the second half of the sixteenth century to 1720.[10] A brief description of how to interpret NGOT can be found in the Appendix. As these tablature books demonstrate, NGOT was not restricted to organ music alone, but was used for intabulations of large-scale polychoral works as well. In the case of the Levocă tablatures the vast majority were intabulated directly from partbooks with no elaborations or keyboard flourishes. “In these intabulations instrumental parts were copied as well as the vocal lines, providing a complete score for each piece. The intabulator clearly organized the large-textured compositions into separate ‘choirs’ of instruments and voices.”[11]

1.6 This study of four of the six manuscripts notated in new German letter notation—namely, MSS 13990a, 13991, 13993, and 13994—will show how organists in the Zips region of present-day northeastern Slovakia might have used the music contained in the six tablature books now located in the Library of the Evangelical Church in Levoča. Several possible applications of these tablatures will be considered, such as the preservation of the music, assistance in accompanying performers, or usage as conductors’ scores.[12]

2. Cantors and Organists, Composers and Dates

2.1 Cantors in German-speaking cities and towns had multifaceted duties similar to those of their North German counterparts, where Protestantism had become the principal religion. Most churches had a prescribed Order of Worship or Liturgy—Kirchenordnung in German—and precise instructions for conducting the liturgical service were laid out in great detail, not just for the cantors, but for organists as well.[13] The cantors, in addition, directed the church and school choirs and were also responsible for the music education of the children. The instructions for the cantor in the Levocă School Regulations (Schulordnungen) are quite detailed:

The teaching of the subject [music] becomes the duty of the cantor, who will teach the rules for the first few days of the week in such a way that he will present them intelligently for the students to practice. The following days he will teach singing, so that he can train the older and younger boys to modulate their voices equally. At the same time, he must explain how to straighten and modulate the voice by narrowing the throat, pulling down the mouth, and forming the vowels when singing. He [must] also draw attention to the fact that not everyone [should] draw their breath simultaneously so that there is a break in singing, but that they take turns breathing and holding out the voice [part].[14]

2.2 There were professional choirs and instrumental groups,[15] but their size and affordability depended on the financial well-being of the particular city.[16] It should also be noted that the responsibilities for music of any sort was quite different at royal courts from church settings. The court Kapellmeister, whether Michael Praetorius, Heinrich Schütz, Gustaf Düben, or even Joseph Haydn, had immense flexibility to organize music productions as needed or required.

2.3 Many organists are known and were generally of local origin and training. Indeed, there was a longstanding tradition in Levoča of providing scholarship assistance to the most promising organ students.[17] There is a considerable amount of information on the organs in the region—including size, disposition, number of keyboards, makers, dates, and cost of construction. The organ in St. James church of Levoča from the early 1630s, for instance, had 1652 pipes, twenty-five registers, six bellows, four windchests, two manuals and pedal, and until the middle of the nineteenth century counted as the largest organ in all of Hungary.[18]

2.4 Dates found in the tablature books of the Levocă collection show entries ranging throughout most of the seventeenth century, a time when turbulent occurrences were common, including the Thirty Years War, the fall of the Kingdom of Hungary, and the dissolution of the Hapsburg Empire. From a review of the contents of these tablatures and the many precise dates found in some of them, composers can be identified, and the origins of the music and how up to date it was can be established. There is music from as far away as Hamburg by father and son Hieronymus and Jacob Praetorius, and from Rostock by Daniel Friderici; likewise, music composed by such notables as Michael Praetorius (Wolfenbüttel), Melchior Vulpius (Weimar), Johann Hermann Schein (Leipzig), Samuel Scheidt (Halle), Heinrich Schütz (Dresden), and Giovanni Gabrieli (Venice) is also found. Numerous other composers, many indigenous to the Zips region and several of unknown origin, are also represented in the collection.[19]

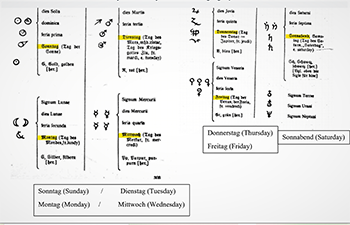

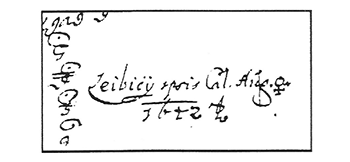

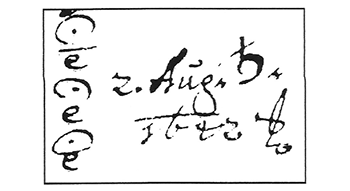

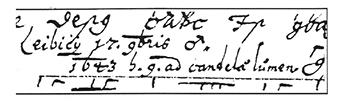

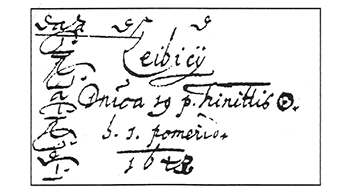

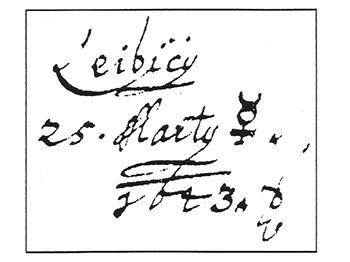

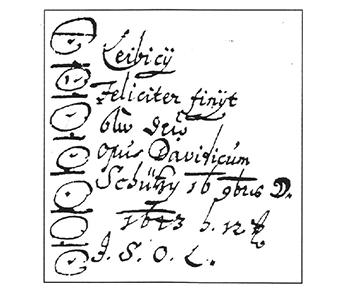

2.5 In his master’s thesis, Jerry Cain presented facsimiles, several reproduced here, of details from MS 13993 showing when and where the scribe penned each piece.[20] Altogether there are about fifty dates in the manuscript; seven are shown here. These scribal annotations include the astrological symbols that represented the days of the week; see the key in Figure 3.

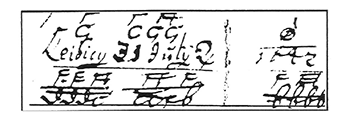

Figures 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, and 10 indicate explicitly that these works were all written in the town of “Leibicÿ” (modern-day L’ubica); the piece in Figure 6 likely originated there as well. The unusual sign following the year in Figures 5, 6, and 10 indicates “Finis” or finished, and a few examples have special notes, e.g., Figure 7, “h. 9. ad candela lumen” (“9 o’clock by candlelight”); Figure 8, “Dominica 19 p[ost] Trinitas” (“the 19th Sunday after Trinity”); Figure 10, “Feliciter finÿt” (“happily finished”) and “opus Davidicum / Schÿtzy” (“Davidic work by Schütz,” i.e., a piece from Psalmen Davids). “J.S.O.L.” in Figure 10 is apparently the initials of the scribe.[21]

3. The Aspect of Tablature Notation

3.1 Only a very small percentage of the works contained in these tablatures constitutes works originally written for organ, the overwhelming majority being intabulations of vocal compositions. Many of the pieces require sizeable choral and instrumental forces, while others call for small three- and four-part choral ensembles. It is precisely this great variety of forms and styles of notation that raises the question: how were the pieces in such manuscripts used? In her work Die Überlieferung der deutschen Orgel- und Klaviermusik, Lydia Schierning offers these thoughts:

All of these manuscripts can be said to be collections of compositions that have been put together according to their practical use. In addition, one or the other tablature was also used as a teaching book, but all manuscripts primarily serve as repertoire collections. The difference in their content lies in the numerous, unequal areas of responsibilities of the organists.[22]

Schierning’s proposition that such manuscripts served as “repertory collections” suggests that the tablatures were meant to function as scores that preserved all the parts of each composition for future performances or for future generations of organists—or even for posterity. Certainly, with many more large-scale works being created than in the previous century, organists and scribes using letter notation produced an immense collection of organ repertory.

3.2 Ironically, however, German-trained organists found themselves in a transitional state with regard to notation during the first half of the seventeenth century. As outlined in the Appendix, it had long been the custom, inherited from the preceding century, for organists to use letter notation with rhythmic signs placed over the letters—a system that extended well into the early decades of the seventeenth century, and, as is commonly known, was even used by J.S. Bach on several occasions when he ran out of staff lines while composing pieces in his Orgelbüchlein.[23] Using staff lines, it should be noted, requires considerably more space than simply using letters. Already by 1624, Samuel Scheidt (1587–1653) was making inroads into modernizing the German system of notation in his Tabulatura Nova by recommending the use of notes instead of letters.[24] This new system was slow to catch on, and even when it finally did become the norm, the young organ student was still expected to be able to read letter notation, as expressed in this satirical quotation from Friederich Niedt’s treatise of 1700, entitled The Musical Guide (Die musicalische Handleitung):

I had first to learn the letters of the German Tabulatur with the crow’s feet written above and beside them—purporting to indicate time—as well as the keys on the Clavier. But before I had but partially grasped this instruction, a few years had already passed. Meanwhile, I thought to myself, “Oh, had I but known that the organist’s art is so difficult, I would have lost all desire for it.”[25]

3.3 Another reference to the use of tablature notation comes from the third volume of Michael Praetorius’s Syntagma Musicum of 1619, where he responds to Agostino Agazzari’s admonition that an organist must have a good grasp of score notation:

However, since most German organists are accustomed to German letter notation (which is not only easy and convenient for them to play from, but also to compose with), it would be very difficult for them to become familiar with staff notation. My advice to them would be to transcribe the compositions completely into their normal letter tablature at first and determine from that how it conforms with the thoroughbass, and whether they could get accustomed to such a thoroughbass through hard work and practice.[26]

3.4 Even as late as 1643, Johann Andreas Herbst refers to German letter notation in his treatise Musica Poetica, suggesting that this method of composing organ music still had its place:

The third modus, way, and manner to compose is with letters according to the usage of the organist, in which the notes are recognizably designated and written with their own clavibus and letters; and this third way has been the most customary from ancient times and is at present still not to be disdained or discarded, as it has its special advantage.[27]

But in revisiting Niedt, some sixty years later, we find the following remark, which reveals that this manner of notation is indeed disdained:

I also realize that a person who knows a little bit about notes and is then led immediately to the thorough-bass will grasp it sooner than those who have played for years according to the German Tabulatur. By contrast, the person who has learned to play things written in Tabulatur will not be able to play even half a line of thorough-bass.[28]

Further on he says that organists who read only tablature notation are “paper organists,” even though they may have been playing for a long time.[29] And finally, he talks about how admirable the old Germans were for devising the tablature method of notating, but at the same time suggests that the primary reason the Italians won all the grand prizes before the Germans is because they never used tablature notation. It is a great deal easier to play from notes than from tablature, he believes, so why not give up the old, clumsy method, in favor of one that is easy and more accurate.[30]

4. The Aspect of Accompanying

4.1 On the prehistory of the basso continuo, Thérèse de Goede-Klinkhamer writes:

During the period preceding that in which organ players began to play thorough bass, it had been customary for the accompanist of vocal polyphonic compositions to compress the different parts of the piece onto staves (intavolatura) or to convert them into an organ tablature. In this way the parts of the composition were duplicated in the accompaniment. Since by the end of the 16th century compositions had become increasingly complex, and the number of parts greater, organ players turned to playing from the bass line only. These basses were unfigured, with at most some sharps and flats added to indicate whether the third needed to be major or minor.[31]

In fact, one of the most important attributes an organist should possess was the ability to accompany from a bass line:

Indeed, one suspects the better musicians of the sixteenth century were able to accompany from a bass line long before Viadana coined the term basso continuo in 1602. They would simply apply their knowledge of counterpoint and the standard harmonic progressions of the day, much as was done with the unfigured bass parts of the seventeenth century.[32]

4.2 Yet not everyone agreed on the best notation to provide an accompanist. Goede-Klinkhamer weighs in again here with this important perspective:

Thanks to their knowledge of counterpoint, organ players were able to judge which harmonies they had to play from the way the bass progressed.… From these [prefaces of printed organ collections] it becomes apparent that not all composers were equally enthusiastic about the new invention. In fact, right up to the second decade of the 17th century there were composers who preferred to have their pieces accompanied from an intavolatura, which they themselves sometimes provided. Others were not against “playing from the bass” per se, but declined to have their basses published with figures, because (as Piccioni says in his Preface): “… this causes confusion with the organ players who do not know them, while the knowledgeable organ player does not need them. Organ players who are not experienced in playing from the thorough bass [basso seguito] had better make an intavolatura.”[33]

Even as late as the beginning of the next century, Niedt, in Chapter 7 of the above-mentioned treatise, refers to this “unfigured” bass: “If nothing is written above the thorough-bass, then only the consonances, namely the third, fifth, and octave are struck.”[34] He discusses the radix unitrisona (three sounding as one) harmony which comes in three forms: radix simplex, harmony consisting of just three notes; radix aucta, the same as the former type, but with doubled octave; and radix diffusa, a spreading out of the three notes into different octaves.

4.3 In the early years of the seventeenth century, Lodovico Viadana had provided his readers with twelve rules in his Cento concerti ecclesiastici to assist them in performing his concertos. Rules six and ten are particularly enlightening to this discussion:

6. No tablature [keyboard score] has been made for these concertos, not in order to escape the trouble, but to make them easier for the organist to play, since, as a matter of fact, not everyone would play from a tablature at sight, and the majority would play from the partitura [open score] as being less trouble; I hope that the organists will be able to make the said tablature at their own convenience, which, to tell the truth, is much better.

10. If anyone should want to sing this kind of music without organ or clavier, the effect will never be good; on the contrary, for the most part, dissonances will be heard.[35]

4.4 With respect to exactly what the accompanist should play, some theorists suggest that there is plenty of flexibility. Agostino Agazzari writes that “there is no need for the player to play the parts as written if he aims to accompany singing and not to play the work as written.”[36] Johann Staden, an organist in Nuremberg familiar with the older styles as well as the new style, writes in the appendix of his Harmoniæ Sacræ of 1616 that “the score need not always be played faithfully. Its purpose is to make clear to the organist which kinds of voices the work uses, so that his accompanying chords can be adapted to them properly.”[37] And Praetorius, who wrote extensively on the concept of basso continuo,[38] suggests that “it is not necessary for the organist to play strictly what the vocalists sing, but to play notes that are consonant with the foundation.”[39]

4.5 In the following chapter, the discussion turns to the issues of basso continuo and figured bass, using examples from the Levoča tablatures.

5. The Aspect of Basso continuo

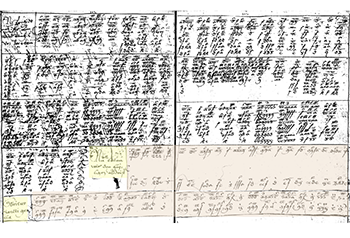

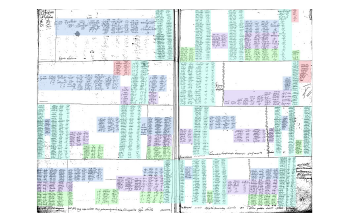

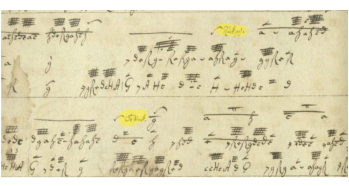

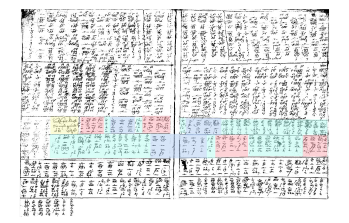

5.1 Several examples from the Levoča intabulations show how composers dealt with the issue of basso continuo. Figure 11 depicts an anonymous composition from MS 13994. Note that one reads the music across the open book, treating the verso and recto as a single page. Two chorale tunes are cited in the last two systems: Nun bitten wir den heiligen Geist begins in system 4 (yellow highlight) and continues across the open book; Spiritus Sancti gratia (German, Des heil’gen Geistes reiche Gnad) occupies system 5 on both pages. Note that the composition, as transcribed by the intabulator, has dropped from six parts in the previous three systems, a setting of the chorale melody Nu frewdt euch ihr arm unnd reich, “6 vo per 4tam,” to just the top and bottom parts in these two pieces—a clear indication that the organist was filling in the inner parts.

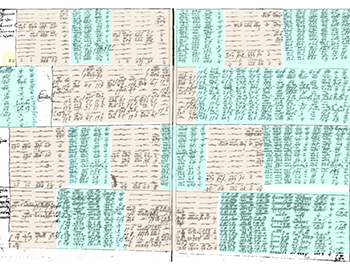

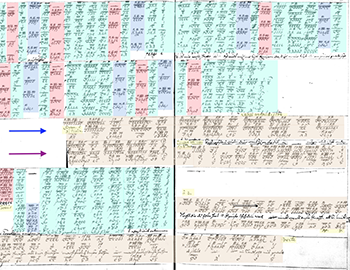

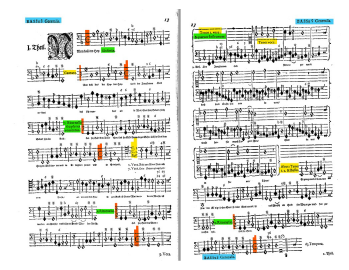

5.2 By contrast, Figure 12 (also from MS 13994), a piece composed by Ján Šimbracký, actually provides the organist with a bassus generalis or general bass line, as highlighted in yellow in the upper left-hand corner. From the way the basso continuo is placed on the page, it can be surmised that it does not accompany the eleven voices in the tutti passages (in turquoise). In the soli sections (in tan) nine voices rest and two are singing (but not always the same two), with basso continuo making twelve parts in all. See systems 1 and 3, verso and recto.

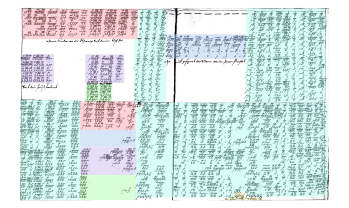

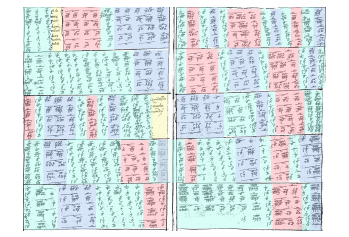

5.3 In Figure 13 from MS 13993, Meine Harfe ist verwandelt in trawren à 8 by Matthias Apelles, system 3 is divided into two parts with the blue arrow representing system 3a and the violet arrow 3b. At the start of 3av is the indication “Sinfon[ia] à 3 violin[i]” (highlighted in yellow), which suggests two violins and cello, with the organist presumably playing from the bottom line. This three-part section continues through 3ar and concludes at the end of 3bv. The short concertato section that follows (system 3br, highlighted in yellow) specifies the alto and tenor of the second choir, but provides three voice parts in all (note that the text, not highlighted, runs across the top where rests are provided for the cantus voice).

This is followed by another short section marked “Chorus” (system 4v, highlighted in yellow), which appears to be divided CCATB|ATTB and which, for two short measures, is polychoral. System 4r returns to two-part writing (“à 2,” highlighted in yellow)—presumably the alto and tenor again—but with the text now placed between the second and third voices; the third voice is much more active than the previous bass line. The meaning of the letters “rp.” and “lf.” at the end of system 4r (highlighted in yellow) is unclear, although they may refer to a change in registration or manuals. This section continues through system 5v–r at which point the duet ends. The concept of “proto-continuo” is clearly playing a role in this piece. The final tutti section of the piece continues on the next pages, as the scribe wrote “Verte” or “turn” at the end of the system (highlighted in yellow).

5.4 Systems 1 and 2 of this facsimile show a “stacked” procedure of writing for divided choirs as opposed to writing in “block” format; more about these two formatting approaches is discussed below. The colors red and blue indicate alternating choirs, while turquoise shows them singing together. At the end of this section (system 2r) the composer or intabulator inscribed the place and date of the composition: “Leibitz” (modern-day L’ubica, roughly 25 km from Levoča), “anno April [Wednesday] 1642” (highlighted in yellow).

6. The Use of the Figured Bass

6.1 Thus far in these facsimiles there has been a preference for writing out the complete parts—a practice that holds true for all of the Levoča manuscripts under study here—rather than reducing the parts to a figured bass. This is all the more remarkable when one consults the partbooks found in the Levoča collection that served as the basis for many of these intabulations;[40] in each set one partbook is marked “General Bass,” as is the case with the Psalmen Davids, op. 2, by Heinrich Schütz. It is interesting to note that even on the rare occasions when parts are reduced, as in the facsimiles above where there is an accompanied solo line, or when only the outer voices are used, the copyist or intabulator never once used any signs or symbols commonly employed when writing thoroughbass lines.

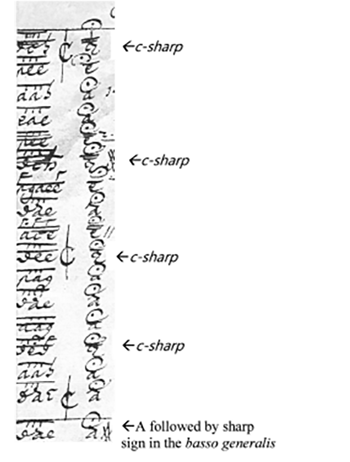

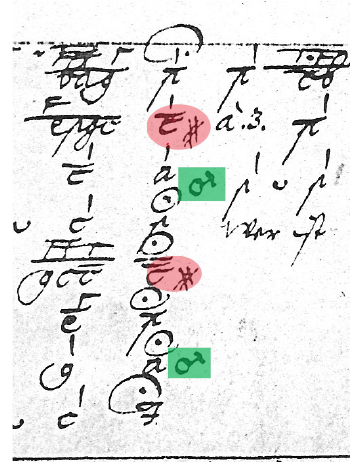

6.2 An exception to this lack of symbols in continuo parts can be found in Ich danke dem Herren von gamzem Herzen by Heinrich Schütz, in MS 13993, as seen in Figure 14. The A at the fermata in the basso continuo is followed immediately by a sharp sign, indicating the raised third. Note that on the preceding page, at the point where choir 2 drops out (shown in Figure 15), the E-major chord has no sharp sign in the basso continuo, a rather perplexing inconsistency. And in Figure 16, taken from Schütz’s Machet die Tore weit, SWV Anhang 8, in MS 13993, there are these symbols: a sharp sign and the Latin symbol for tertia or third (a circle with a right-slanting arrow), both perhaps cautionary signs suggesting that the third should not be lowered. Both seem superfluous for the F-major chord they accompany, as seen in Example 1.

6.3 As suggested above (par. 4.2), several theorists of the time expressed their opinions concerning the use of figures in a thoroughbass part. In 1607 Agazzari stated:

As no definite rule can be given, the player must necessarily rely upon his ear and follow the work and its progressions. But if you would have an easy way of avoiding these obstacles and of playing the work exactly, take this one, indicating with figures above the notes of the bass the consonances and dissonances used with them by the composer….[41]

Adding figures above the notes, according to Agazzari, has more to do with convenience than method, as he says that one can assemble a large number of pieces with very little trouble by using a figured bass; in addition, the beginner is no longer bound to the score, something that is not only difficult to use, but likely to promote error, due to the many parts that must be followed simultaneously—especially when it is concerted music and one has little or no time to prepare.[42]

The need to save space, he concludes, is alone sufficient ground to use the figured bass, for if an organist were to make a score of all the works that are sung in the course of a year in just one church in Rome where concerted music is performed, he would need to have a library larger than that of a Doctor of Laws.[43]

6.4 Adriano Banchieri was rather uncomplimentary regarding the whole idea of thoroughbass. In his Conclusioni nel suono dell’organo, published in Bologna in 1609, he writes:

Because it is easy to play from a Basso Continuo, many organists nowadays are highly successful in concerted playing. But in their great vanity on account of their sureness in playing with others, they give little thought to exerting themselves in improvisation and playing from score, whereas it is in this very domain that many a good man has made himself immortal. So that, in short, we shall soon have two classes of players: on the one hand Organists, that is to say, such as practice good playing from score and improvisation, and, on the other hand, Bassists who, overcome by sheer laziness, are content with simply playing the Bass. I do not mean to say that playing from a Basso Continuo is not useful, and is not easy, but I do say that every Organist ought to seek to play the Basso Continuo in accordance with sound rules.[44]

6.5 Responding to Agazzari’s comment that some people might regard the organist who uses numbers and symbols as clumsy and stupid, Praetorius writes:

To that I respond that without the use of these figures one is far more likely to think him a fool, whose characteristics, among other things, include having to guess and stumble around making thousands of mistakes. If the organist presumes to anticipate the composer’s intentions and thoughts he will come across as deranged and as a simpleton worthy of ridicule.[45]

To be sure, the score[46] of all parts was created in an earlier time, and one was supposed to be able to play from it accurately as written, which was certainly done; whoever has a good grasp of it and plays from it expediently can still use it as well as ever.… The thoroughbass was invented so that one could immediately play along in a concerted piece without such diffuseness and difficulty and thus produce a beautiful harmony.[47]

But it was recognized by some that the many dissonances that were heard were a result of the thoroughbass simply being played artlessly, since anyone could apply the rules of music in his own capricious manner. Consequently, it was vitally important to invent a method by which one could play correctly, without mistakes, and conform as much as possible to the composer’s composition. There was no easier way to achieve this than through the use of figures, by which any small boy only slightly familiar with the system could play the piece so well and free of dissonances, as if he were playing from the complete score.[48]

… the sharp and flat signs and the numbers 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, etc. denoting major and minor thirds and sixths above the bass line must be carefully observed.… It is not necessary for the organist to play the vocal parts as they are being sung, but to play concordances to the foundation independently.[49]

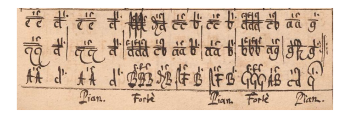

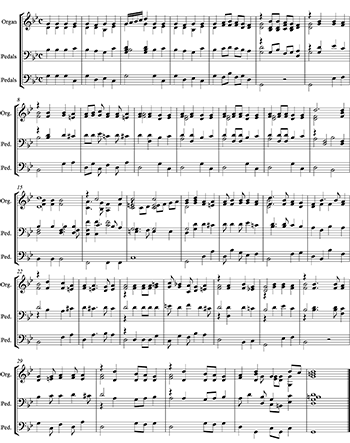

At this point, as seen in Figure 17, Praetorius provides the reader with an example of proper basso continuo execution: a two-line figured bass (blue highlighting), followed immediately by its resolution (green highlighting).[50] Under the example he writes: “Those who are not accustomed to note tablature can quite justifiably transcribe it into German letter notation and deduce from this how the inner parts are to be employed.”[51]

7. The Aspect of the Conductor’s Score

7.1 The theoretical discussions presented thus far demonstrate the various approaches an organist might have taken with respect to the thoroughbass, and how the organists in the Zips region of eastern Slovakia practiced the art of accompanying from German letter notation in the Levoča intabulations. Another type of intabulation found in these manuscripts—which might be described as conductors’ scores—will now be considered.

7.2 It may come as a surprise to some, but the idea of creating a score for a composition after it was written did not seem important to composers prior to the seventeenth century. Whether in manuscript or printed form, the music was either arranged in books according to their vocal range (e.g., cantus partbook, altus partbook, etc.), or it was written in one of many choirbook formats, in which each voice was placed in its own area of the open book—for instance, the cantus voice on the upper left, the tenor voice below it, and the altus and bassus parts on the opposing page with the altus above the bassus.[52]

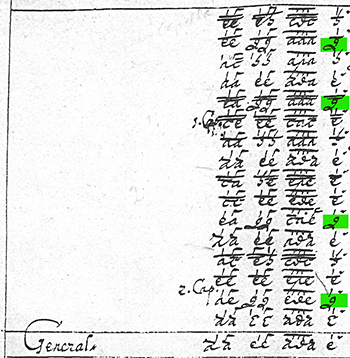

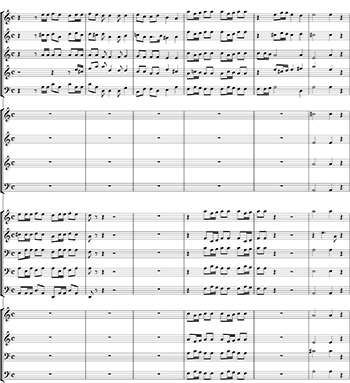

7.3 Praetorius recommends using the thoroughbass part as a score, as it not only indicates which choirs or soloists are performing at any given moment but provides a running commentary on the harmonic progressions and meter changes of the entire piece. He finds this especially beneficial to the music director or other conductors for purposes of cuing the performers, and suggests further that parts be copied out and distributed to the organists and lutenists of the various choirs with their specific parts underlined in red.[53] While such detail does not appear in the Levocă tablature books, it is illustrative to observe the specificity in the following bassus generalis pages from Michael Praetorius’s Polyhymnia Caduceatrix, no. 17, Nun komm der Heiden Heiland à 12 “cum Symphonia & Ritornello,” in Figure 18. I have highlighted the part name in blue, meter changes in red, portions scored for instruments in green, and voice parts in yellow. The items in green and yellow clearly show the formal organization of the piece into sections.

7.4 With the amount of detail Praetorius provides, the music director has everything he needs to perform a large-scale work. Note that on the second page, Praetorius introduces a staff for the tenor soloist, who is accompanied by four instrumentalists. Organists using the Levocă tablature books did not have the luxury of such a bassus generalis, however, and had to rely on the intabulations that are no larger than 22.5 x 32.8 centimeters (roughly 8.5 x 13 inches), which would easily fit on the note desk of a continuo organ.

7.5 The third and final part of the treatise Musica Nova: Newe Singekunst of 1626 by Nicolaus Gengenbach is a compendium of foreign terms in common use at the time—first the important Latin and Greek words, then those in Italian. He readily admits on page 127 that he was assisted by Praetorius’s Syntagma Musicum, volume 3, and refers his readers there for further instruction. He defines basso continuo as follows:

Basso continuo is a special, newly discovered part, which carries the fundamental line through the entire piece for organists and lutenists, etc., so that they can skillfully play along exactly as if the concerto or motet were copied out. Likewise, it is quite convenient for choir directors when it is transcribed. Then one can see, for one thing, when a proportion begins and ends in the middle of the piece. Thereafter, when only one voice is accompanied by the organ, underneath is written: solo voice, soprano solo, alto solo, etc. Likewise, when a ritornello or ripieno comes in. In the same way, when the first, second, third, or fourth chorus, or when two of them sing together, it is a fine compendium for the director, and a good novice, when it is necessary to signal and assist one choir or another with entrances, etc.[54]

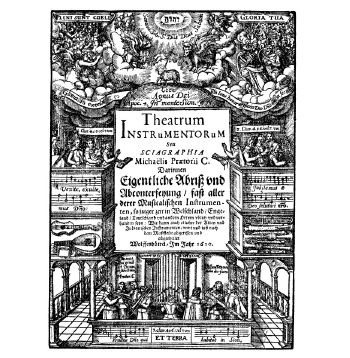

7.6 As uncommon as it may appear that someone was actually conducting these multi-choir pieces, it is clear from these excerpts that both Praetorius and Gengenbach are speaking to music directors. If these quotations are not proof enough, perhaps this well-known illustration seen in Figure 19, taken from the title page of Praetorius’s Theatrum Instrumentorum of 1620 (an appendix to volume 2 of Syntagma Musicum), will be sufficiently convincing.

Here, the primary director is leading a group in the lower center, which includes the large organ. Assistant directors are seen in the split balconies directing smaller groups including continuo organs, but clearly coordinating their efforts with the main director.[55] It cannot be ascertained with certainty whether the principal director is using notated music from which to lead the ensemble, but it is quite clear that his assistants are holding such music in their hands. Moreover, in discussing the placement of performing groups in Syntagma, volume 3, Praetorius specifically refers to keeping the beat by following the thoroughbass part:

With the help of the thoroughbass part, the choirmaster, or whoever is responsible for keeping the beat, must lead the group of musicians in the choir and the trumpeters in the nave [of the church].… All members must be able to see him and follow his lead.[56]

7.7 Twenty years later, André Maugars, a French viol player, wrote a letter from Rome describing a service he witnessed at the Santa Maria sopra Minerva church. The following excerpt from his letter provides conclusive evidence that conductors were not only a common feature of performances at this time, but highly necessary:

This church is rather long and wide and there are two large elevated organs, one on each side of the main altar, where they had also placed two choirs. Along the nave there were eight other choirs, four on one side and four on the other, raised on platforms eight or nine feet high, an equal distance from one another and all facing one another. With each choir there was a portative organ, as is the custom. The leading conductor beat [sic] the measure for the main choir, accompanied by the best voices. With each of the others there was a man who did nothing but keep his eyes on the leading conductor, to conform his own beat to the leader’s; in this way all the chorus [sic] sang in the same time, without dragging.[57]

7.8 At about the same time Niedt is denigrating the use of German letter notation, its use is mentioned in Andreas Werckmeister’s Musicalische Paradoxal-Discourse, published posthumously in 1707; nonetheless, Cleve Johnson asserts that Werckmeister (1645–1706) was only reporting a practice that had fallen into disuse, inasmuch as he consistently used the past tense. Werckmeister says:

… as I have known different directors who set their scores in German tablature and sang and conducted from them. I can thus attest [from] the eminent [Heinrich] Grimm’s own hand that he directed from the German tablature or letters.[58]

A little further on he continues:

And whether or not a singer or director understands the keyboard, he can still get the harmony and manner of singing in his head by using the letters. If he does not know the clefs and how they sound together, he will never be able to sing well using the staff lines.[59]

8. Performance Settings and Conditions

8.1 It is not always certain who was responsible for rehearsing and leading performances of large-scale works—it may have been the cantor or the Kapellmeister, a person who in most cases held the post of organist before being promoted, or it may in fact have been the organist. In any case, the enterprising leader who was responsible for directing these works and who preferred more concrete information than a thoroughbass part provided, would often transcribe each piece from the partbooks, in proper succession, into German tablature notation, so that he would be able to see at a glance which choir or combination of choirs—including instrumental choirs—was to be performing at any given time, and thus armed, assist them with their entrances and exits.

8.2 The situation at St. James church in Levoča may have been similar to that in other German-speaking cities where the cantor was responsible for the principal churches but was able to provide choral music (as opposed to simple hymn singing) at only one church per Sunday. The primary difference is that the cities in the Zips region were very modest in size and may have needed to enhance their performance forces by asking for assistance from churches in the surrounding area, such as Kesmark/Käsmark (Kežmarok), Leibitz (L’ubica), Kirchdrauf/Kirchdorf (Spišské Podhradie), Neundorf/Neudorf (Spišská Nová Ves), and possibly even Deutschendorf (Poprad)—most no further distant than 25 kilometers from Levoča, and therefore less than a half day’s walk (refer to the maps in Figures 1 and 2). It seems altogether likely that even if those independent churches had no need for additional singers or instrumentalists from these neighboring towns, they would want to share their music with those congregations.

8.3 It should be pointed out (as implied above in par. 1.3) that the six collections of intabulations located at the Protestant Rectory did not all originate in Levoča but were collected at the end of the nineteenth century and deposited there for safe keeping.[60] Ján Šimbracký, cited above (see n. 3), was, for instance, active in nearby Kirchdrauf (modern-day Spišské Podhradie). Organists known to have been active in Levoča include Johann and Caspar Plotz (father and son) and Samuel Marckfelner.

9. The Polychoral Scores

9.1 The next group of facsimiles depicts a variety of large-scale polychoral intabulations that could possibly have served as conductors’ scores.

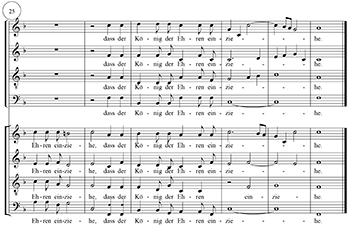

9.2 Figure 20, Dixit Dominus Domino meo by Hieronymus Praetorius, comes from MS 13990a and is written for twelve voices divided into three choirs of four parts each. The fact that it is textless does not necessarily mean that it was performed purely instrumentally, but it is certainly conceivable that it could have been. Notice how the choirs enter and exit—choir 1 in red, choir 2 in blue, choir 3 in purple—and how and when they perform together—highlighted in turquoise—and then try to imagine playing from this “score.”

Attempting to play these tall columns of chords on the organ in any kind of literal fashion is obviously quite out of the question. As a rehearsal score, this layout, while not always completely legible, provides the director with a great deal more specificity than an organist’s thoroughbass line, and, just from a visual standpoint, this overview enables him to assist the choirs with their entrances and exits more effectively. For a transcription through the first tutti on the second system, see Example 2.[61]

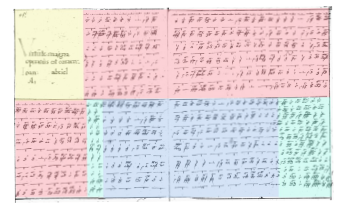

9.3 Figure 21, an Officium or Missa Brevis for sixteen voices by the as-yet-unidentified composer “A.S.O.C.,” is taken from MS 13994 and demonstrates even more conclusively that the user would have had to be the conductor. The four clearly separate choirs of four voice parts each (ch. 1–red; ch. 2–blue; ch. 3–purple; ch. 4–green; tutti–turquoise) would most likely have been placed in different locations in the church, possibly even on elevated platforms. Any one of the choirs might have been instrumental or perhaps a mixture of instruments and voices, and each would have had its own continuo instrument. The text would have been distributed to the parts being sung and adapted to the notes and rhythms by the singers. Naturally, the homorhythmic sections would have been performed similarly by all voices.

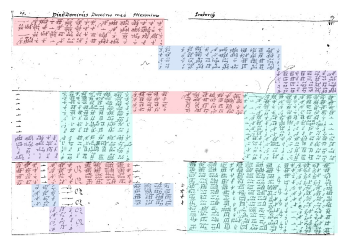

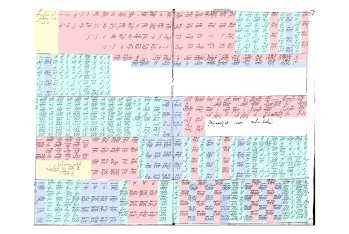

9.4 Figure 22 (with an analogous color scheme) comes from a setting of Psalm 128, Wohl dem, der den Herren fürchtet, SWV 44, by Heinrich Schütz, as found in MS 13993. The place and date (highlighted in yellow) are given as “Leibicÿ / 12 Novembris 3 [Thursday] 1643.” The setting consists of as many as eighteen separate parts. Though the piece is not as clearly divided into choirs as those in the previous two illustrations, there are occasions (see system 1r) in which only four voices are singing. In system 2v the clear layout of the score might have aided the director in bringing in the singers in these staggered entrances (after the first tutti in that system). Note that the text is found only when three of the four choirs are each singing by themselves—see underlaid text in system 1v–r—except for the word “siehe” in the lowest voice after the first tutti chord in system 1v. It is hard to imagine how an organist could have played from a part such as this.

9.5 Though the organ intabulation does not indicate any instruments, the partbooks (Schütz, Psalmen Davids, op. 2) call for one violin, four cornetts, three trombones, solo cantus and bassus, and continuo, plus two four-part choirs, as shown in Example 3. Example 4, a transcription (without underlaid text) made from the partbooks, includes system 1 of the tablature, from fol. 31v to the tutti entrance on 32r.[62] It should be noted that the vertical order of the choirs in the transcription follows the tablature, whereas in most modern editions the two five-part instrumental choirs (red and purple in the facsimile) are given on top, then the two four-part vocal choirs (blue and green) take the lower eight staves, with the bassus generalis at the bottom.

10. Rare Instructions in Organ Tablatures

10.1 Directions concerning dynamics, manual usage (i.e., registration), and indications of alternating choir and organ passages (alternatimpraxis) are rare in organ works in the seventeenth century—especially in intabulations—and none has been found in the manuscripts under study here. The following three facsimiles present examples of each of these topics.

10.2 Figure 23 depicts a portion of a work by Giovanni Valentini entitled “Echo à 3,” which clearly shows where the loud statements and soft echoes take place.[63]

10.3 Figure 24 shows An Wasserflüssen Babylon by Johann Pachelbel, copied by J.S. Bach’s student Johann Marin Schubart, in the years 1707–8.[64] Shown here is one of several places where a shift from the Rückpositiv (upper system, top line) to the Oberwerck (middle of the lower system, also top line) occurs.

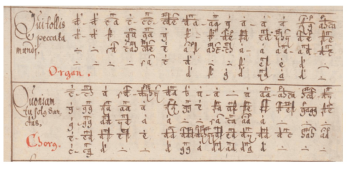

10.4 Figure 25 provides an example in which the practice of the organ alternating versets with the choir is made demonstrably clear. The upper system, on the text “Qui tollis pecatta mundi,” is not sung but played on the organ. This is noted by the scribe in red. The lower system has the text “Quoniam tu solus Sanctus,” which was to be sung by the choir (or celebrant), and it is clearly labeled by the scribe “Chorus,” in red.

10.5 In Syntagma Musicum, vol. 3, Praetorius gives insight into how the organist might adjust his registration and manual usage when accompanying solo singers and choirs:

If all voices … periodically join in together in such a concerto in which a few solo voices have previously sung alone, the organist should indeed use both manual and pedal keyboards simultaneously, but refrain from pulling additional stops, as the delicate and soft tones of the singers would otherwise be completely overwhelmed by the considerable sound of the many organ stops which would cause it to be heard more prominently than the singers.

However, some composers such as Agostino Agazzari and Bastiano Miseroca hold the opinion that the organ should engage more stops when the full ensemble enters. This can be accomplished more conveniently if two manuals are available. One manual could have a very soft registration and the other a louder one so that in such changes one switches to the other keyboard. For few voices one can use the soft register, but when many more voices join in, the louder or doubled one can be used together with full chords. However, with few voices, chords can be reduced in size and fewer stops used so that the two or three solo voices are not drowned out by the numerous chord tones and loud organ pipes.[65]

11. “Blocked” and “Stacked” Format

11.1 The purpose of the final set of facsimiles is to demonstrate the rather unusual way organists occasionally intabulated compositions for divided choirs. In all cases red and blue highlighting differentiates choir 1 and choir 2; turquoise shows them singing together. The typical procedure as shown in the second system of the anonymous work in Figure 26—Singet dem Herrn ein newes Liedt from MS 13991—was to indicate graphically how the choirs were to be divided, and when they were to perform together. In this intabulation when only one choir is active, the other choir’s space is filled with rests, thus making it perfectly clear which choir is singing. While this is typical, it is not always the case, as some copyists, perhaps in haste, only place rests in the top voice, while other scribes simply leave the entire space blank. This type of “block” notation not only enables the organist to assist the choirs with their entrances and exits but provides him with what might be looked upon as a diagram or chart depicting manual and registration usage. With this “block” format he can assign registrations of differing timbres to each manual and choir and use a larger sound for the tutti passages, as described in the Praetorius quotation above.

11.2 Figure 27, Giovanni Gabrieli’s Virtüte magna operatüs est coram in twelve parts from MS 13990a, is a clear example of what can be called “stacked” notation, meaning the amalgamated parts are lined up (i.e, stacked) vertically by pitch, with the two choirs interleaved.[66] By using this format, the organist was able to retain the integrity of the entire piece by placing the voice parts one below the next, from the highest to the lowest, but with rests inserted for the tacet choir. The ability to differentiate one choir from the other, however, is reduced to such an extent that the above-mentioned nuances would probably have been unattainable.

11.3 Divining the intabulator’s intent from the twenty-first century perspective is, of course, impossible, so attempting to explain his approach to copying parts from as many as ten to fifteen partbooks—whether into separate choirs, as in Figure 26, or with the two choirs interleaved, as in Figure 27—would be pure speculation.

11.4 Figure 28 shows Samuel Scheidt’s Angelus ad pastores ait (SSWV 77) from MS 13993. Ján Šimbracký, the organist and probably the intabulator, chose the “stacked” format to intabulate this eight-part work, but he omitted the rests when one or the other choir is silent. A score of this work is available online.[67] The intabulation omits the opening sinfonia and begins at m. 29 of the edited score (“Sans instr.”); system 1v ends in the middle of m. 44; the beginning of the imitation between choirs 1 and 2 in system 2v, after the tutti section, occurs at m. 70.

11.5 In Figure 29, from MS 13994, the title of the piece beginning in system 3, Also hatt Godt die welt geliebt (highlighted in yellow), indicates that the piece is for eight voices, but in actuality it appears to be a work for four voices in which the soprano and bass (in red) alternate with the alto and tenor (in blue) and these duets are interspersed with occasional tutti passages (in turquoise).

11.6 The final illustration, shown in Figure 30, is taken from MS 13994. Et in terra pax hominibus bone voluntatis is excerpted from the Officium super Casta novenarum in eight parts. Even though it is written in “stacked” format, the clarity of the parts on the page is such that one could conceivably detect the demarcations of the divided choirs, even while playing, and thus incorporate the desired registral and timbral subtleties.

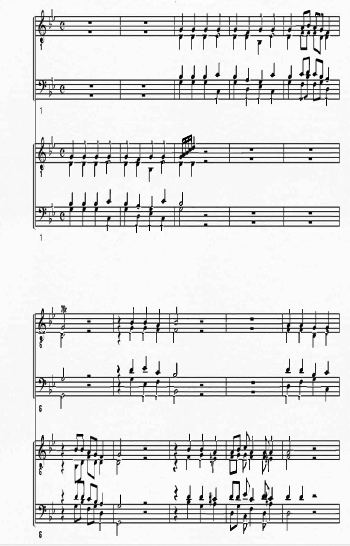

Two transcriptions give this piece in modern score notation. Example 5 represents the “stacked” approach to notation. Rests have been eliminated to reduce clutter on the page, but all doublings have been retained. Seen in this light, it is doubtful that this composition would be recognized as a work intended for divided choirs. Audio Example 1 demonstrates that if the music were played in this fashion, it would not be possible to differentiate one choir from the other.

Example 6 is a transcription of the same piece using the “block” format notation. It is plainly obvious that the divided choir approach to performing this work would be greatly enhanced by this format. Audio Example 2 demonstrates that with the clear separation of choirs in the block format approach, an organist could easily arrange for each choir to have its own registration, which, as heard in this example, enables the listener to distinguish between the two choirs with little or no effort.

12. Conclusion

12.1 In summary, this study has established that organists of the Zips region of Slovakia relied on German letter notation for a multitude of purposes, perhaps most importantly, to intabulate works for practical reasons. It is clear from an evaluation of the contents of these manuscripts that the organists were playing works by internationally known, contemporary composers, that they were composing their own works, and that they had the personnel to mount large-scale, Venetian-style polychoral performances involving the use of a variety of instrumentalists and singers. And finally, it has been shown that, although they had the know-how to play from a thoroughbass line or a reduced set of parts, they apparently preferred to play—and direct—from intabulations that served as conductor’s scores.[68]

Acknowledgments

The coloring of the facsimiles in this study was provided by Chris Rathbun to whom many thanks are due. Thanks to my friend and colleague Charles Brewer for sharing his thoughts on some of the abbreviations found in the dates. I am most appreciative of the many communications Marta Hulková and I had and the valuable information she willingly shared. I am grateful to Lois Rosow, editor-in-chief of the Journal, for her skillful and thoughtful editing of this article and for her patience in working with me.

Appendix

Appendix. An introduction to NGOT notation

Figures

Fig. 1. Spiš (Zips) region, showing Levoča (Leutschau) with distances to related cities

Fig. 2. Principal cities with Levoča tablature connections

Fig. 3. Astrological symbols for the days of the week

Fig. 4. “Leibicÿ 31 July [Thursday] / 1642”

Fig. 5. “Leibicÿ ipsis Cal. August [Friday] / 1642 [Finis]”

Fig. 6. “2 August [Saturday] / 1642 [Finis]”

Fig. 7. “Leibicÿ 17 Novembris [Tuesday] / 1643h. 9. ad candela lumen”

Fig. 8. “Leibicÿ / Dominica 19 p[ost] Trinitas [Sunday] /h. 1. pomerio/ 1642”

Fig. 9. “Leibicÿ / 25 Marty [Wednesday] / 1643”

Fig. 10. “Leibicÿ / Feliciter finÿt /… / opus Davidicum / Schÿtzy16 Novembris [Monday] / 1643 … [Finis] / J.S.O.L.”

Fig. 11. Anonymous composition, MS 13994

Fig. 12. Piece composed by Ján Šimbracký, MS 13994

Fig. 13. Matthias Apelles, Meine Harfe ist verwandelt in trawren à 8, MS 13993

Fig. 14. Heinrich Schütz, Ich danke dem Herren, MS 13993: sharp sign in figured bass

Fig. 15. Schütz, Ich danke dem Herren: G-sharps in choir but none indicated in figured bass

Fig. 16. Heinrich Schütz, Machet die Tore weit, MS 13993: sharp signs and the tertia symbol

Fig. 17. Michael Praetorius, Syntagma Musicum, vol. 3: a figured bass and its resolution

Fig. 18. Michael Praetorius, Polyhymnia Caduceatrix (1619), bassus generalis partbook: no. 17

Fig. 19. Title page of Michael Praetorius, Theatrum Instrumentorum (1620)

Fig. 20. Hieronymus Praetorius, Dixit Dominus Domino meo, MS 13990a

Fig. 21. Officium or Missa Brevis for sixteen voices by unidentified composer, MS 13994

Fig. 22. Heinrich Schütz, Psalm 128: Wohl dem, der den Herren fürchtet, MS 13993

Fig. 23. Giovanni Valentini, “Echo à 3,” showing forte/pian markings. Mus.ms. 4485, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

Fig. 24. Johann Pachelbel, An Wasserflüssen Babylon, showing manual shifts. Fol. 49/11, Anna Amalia Bibliothek, Weimar.

Fig. 25. An example of Alternatimpraxis (ca. 1630). Ms. Lynar B 3, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin.

Fig. 26. Anonymous, Singet dem Herrn ein newes Liedt, MS 13991: “block” notation

Fig. 27. Giovanni Gabrieli, Virtüte magna operatüs, MS 13990a: “stacked” notation

Fig. 28. Samuel Scheidt, Angelus ad pastores, MS 13993: “stacked” notation with omitted rests

Fig. 29. Anonymous, Also hatt Godt die welt geliebt, MS 13994

Fig. 30. Anonymous, Et in terra pax hominibus bone voluntatis, MS 13994

Examples

Ex. 1. F-major cadence in Schütz, Machet die Tore weit

Ex. 2. Hieronymus Praetorius, Dixit Dominus Domino meo

Ex. 3. Schütz, Wohl dem, der den Herren fürchtet: original clefs and instrumentation

Ex. 4. Schütz, Wohl dem, der den Herren fürchtet: transcription

Ex. 5. Transcription of anonymous Et in terra pax hominibus in “stacked” format

Ex. 6. Transcription of anonymous Et in terra pax hominibus in “block” format

Audio Examples

Audio Ex. 1. Anonymous, Et in terra pax hominibus in “stacked” format

Audio Ex. 2. Anonymous, Et in terra pax hominibus in “block” format