The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 31 (2025) No. 1

“All kiend of Musicke: and Instriments of Warr”: British Travel Writers in Seicento Venice

Alana Mailes*

Abstract

A large number of British travelers ventured into the Italian peninsula in the early seventeenth century, sparking an enduring vogue for Italian music in Britain and a resulting “Italianization” of English music. Few musicological studies on this period of Anglo-Italian musical exchange have looked beyond the activities of professional composers and performers. This article gathers together several different descriptions of music in English and Scottish travel accounts of Venice, in both printed and manuscript sources from the first half of the Seicento, to examine how this group of visitors from a nascent rival maritime empire collectively responded to cultural life in the Venetian Republic. These writings––which comment on everything from opera and courtesan singers to elaborate state ceremonial and the sacred rites of minoritized religious communities––reflect an emerging British cosmopolitanism rooted in inter-imperial power dynamics on the early modern Mediterranean. These accounts were penned by famous authors including Fynes Moryson, Thomas Coryat, Richard Lassels, and John Evelyn, as well as by lesser-known travelers such as Bullen Reymes and James Fraser.

3. Catholic Institutions and Ceremonial

5. Jewish and Greek Orthodox Rites

1. Introduction

1.1 Italian influence is a dominant theme running through histories of Tudor and Stuart music. The tale is typically told as a narrative of Italian court musicians and repertoires exported to Britain and of professional English musicians who picked up Italian compositional techniques while traveling across continental Europe. Few musicological studies have explored other dimensions of early modern Anglo-Italian musical interactions, and the broader geopolitical and economic stakes of this sustained period of transcultural exchange are virtually never considered.[1] And yet, the seventeenth century saw a game-changing renewal of diplomacy between England and Catholic Europe that encouraged international travel across confessional lines, attempts at a religiopolitical alliance between England and the Republic of Venice, a flurry of British merchant activity in Venice that would facilitate England’s eventual commercial conquest of the Mediterranean, and the beginnings of a famed cultural phenomenon, the Grand Tour, in which countless Englishmen flocked to the Italian peninsula on prescribed educational journeys to cultivate a cultural refinement and cosmopolitanism that would serve England’s global ambitions.[2] Consideration of this wider historical context encourages a reading of England’s musical “Italianization” as a form of inter-imperial mimesis, driven by a spirit of expansion, emulation, and competition.[3]

1.2 This article gathers together all descriptions of music that I have found in surviving English and Scottish travel accounts of Venice from the first half of the seventeenth century, to examine how this group of foreign amateur musicians and other visitors from a nascent rival maritime empire collectively responded to cultural life in the Venetian Republic. In bringing together this diversity of printed and manuscript sources, I suggest that these writings on music reflect an emerging British cosmopolitanism rooted in inter-imperial power dynamics on the early modern Mediterranean. This assemblage of British chroniclers ranged from aristocrats and students to ecclesiastics, itinerant merchants, and professional travel writers. All of them were men and nearly all would have identified as English, with the exception of one Scottish traveler, the Protestant cleric James Fraser.[4] All quoted authors and texts are listed in Table 1, in chronological order of their travels.

1.3 Venice was a prime destination for British grand tourists and other peripatetics, who wrote in detail about the many varieties of music that they heard in Italy. Their travelogues are certainly not a monolith, but some commonalities do emerge in their descriptions of music in the Serene Republic. First, most British travelers remarked on music’s general importance to Venetian sacred devotion, civic ritual, and daily life. Italians are frequently portrayed as a highly musical people; one author, the English priest and travel writer Richard Lassels, even asserted that Italians were physio-psychologically predisposed towards music making. Second, British travelers tended to write about Venetian musical pageantry with awe, associating the Republic’s ceremonial music with slave labor and military spectacle. Third, this set of writers usually marveled at the many musical and organological technologies showcased by musical performances in the Republic, known as a major center for instrument making and music printing. Multiple British travelogues note that Venetian instrumental ensembles, virtuosic vocalists (especially women and castrati), stage machinery, and other novel astonishments had a powerful, rapturous effect on spectator-auditors.[5] Finally, multiple British tourists to this “world city” participated in a larger national project of global knowledge acquisition through proto-ethnological study of foreign musical practices, including those of local religious and ethnic minorities.[6]

1.4 The voyages and discoveries made during the English age of exploration, in conjunction with the advent of print, engendered a widely circulated corpus of travel literature, framed by an emergent English Protestant national identity and driven by commercial, imperial, and colonial ambitions.[7] Analyzing English travelogues of India, for example, Pramod Nayar has argued that early modern English travel writing cultivated a socially energizing cultural imaginary of foreign lands, inspiring readers to quest for distant, decadent, and uncharted places. Discovery was a mode of “imaginative mapping” that demystified the foreign through empirical inquiry and would later inform state colonial ventures. These knowledge-gathering efforts abroad were an exercise in self-definition: through repeated cultural comparison, English travelers began to see themselves as a superior race worthy of jurisdiction over a colonial empire.[8] In this way, many seventeenth-century British travelogues laid the groundwork for England’s subsequent global enterprises; some travelogues were even written by government officials and functioned as didactic advice texts that primed state agents for entry into foreign territories.[9] Travel writing also served as a vehicle for British participation in international debates about the body politic, societal structure, political representation, individual liberties, religious persecution, foreign cultural influence, and state rivalries.[10]

1.5 A handful of these travel texts were published for commercial purposes while some have remained hidden away in private collections down to the present. Whether these accounts were truthful or fanciful, and whether they were written for private reference, family, friends, or a public readership, collectively these many descriptions of music abroad provide significant insight into early modern British perceptions of Venice and its musical cultures. On the one hand, the travel accounts herein build on one another and on earlier practices of travel writing outside of Britain, for example Franciscus Schottus’s Itinerarium Italiae rerumque Romanorum libri tres (Antwerp: Jan Moretus, 1600). A genealogy of their numerous shared narrative traditions is beyond the scope of this study, though it is important to remember that the chronicles of British travel writers in Italy were guided by a shared itinerary, narrative structure, and language specific to the European and especially English travelogue genre. On the other hand, although early modern British travel writing was highly derivative and formulaic, the opinions of any one author quoted below should not be assumed to reflect any other individual author’s point of view. I aim not to conflate the experiences of these travelers but to highlight what their diverse accounts have in common. Any general claims that I make should be taken to mean that commonalities arise in multiple but not all of these texts.

2. Italian Musicality

2.1 Most evidently, the majority of these British travelers to Venice agreed upon a general excellence of Italian music, and they noticed a widespread appreciation for music throughout the peninsula. The travel writer John Raymond, who published an account of his visit to Venice in the 1640s, characterized Italians as “so addicted to Musick, especially that of the Voyce, (which indisputably is the best …).” He claimed that in Italy there was “no Fachin [porter] or Cobler but can finger some Instrument; so that when the heats of the Day are tyr’d out to a coole Evening; the Streets resound with confused, yet pleasant Notes.”[11] The scientist, writer, and colonial administrator John Evelyn evoked a similar scene of gentle, sonorous chaos when he recalled that he had heard individuals on the Grand Canal of Venice “singing, playing on harpsichords, & other musick & serenading their Misstriss’s….”[12] Like Raymond, Evelyn also described countryfolk around Naples as “addicted to Musick.”[13] Evelyn kept a much-cited diary of his journey to Venice in the 1640s and studied for a short time at the University of Padua. He wrote often about music, played the lute, and took theorbo lessons while in the Veneto. See Fig. 1.[14]

2.2 Richard Lassels, who chronicled a journey that he took with the Catholic noblewoman Catherine Whetenall and her husband, Thomas, through the peninsula in the Jubilee Year of 1650, penned an especially direct discourse on the supposedly innate musicality of Italians. A revised version of his travel account was published posthumously in Paris and then in London before it was also translated into French and German. It became an influential guidebook of the period, and Lassels famously coined the term “Grand Tour.”[15] Lassels described Italians as

… good for Nunciatures Embassies, and State employments, being men of good behaviour, looks, witt, temper and discretion. They are great lovers of musick, meddals, statues and pictures, as things which either divert their melancholy, or humor it. In fine Pliny somewhere sayth, that the Italians were a people chosen by the Gods for to teach man manners.[16]

2.3 In Lassels’s estimation, musicking was a civilized and also civilizing means by which Italians maintained control over their own inherently unstable emotional state: “They have strong phancies and excellent iudgements both together, which make them such good politicians, painters, Poëts, musitians and ingeniers; but withall too jealous and melancholick.”[17] Lassels explained that young Englishmen could learn from the civilizing, mood-stabilizing influence of Italian cultural practices by traveling to Italy and “viewing the several courts, studying their maxims, imitating their gentile conversation, and following the sweet exercises of musick, painting, architecture, and mathematicks.…”[18]

2.4 This portrayal of a melancholic Italian temperament parallels a handful of aphorisms that the travel writer and political secretary Fynes Moryson published in 1617 after he had journeyed to the Veneto in the 1590s, where he had briefly been enrolled at the University of Padua.[19] He described the Italian style of singing in three different ways: as bleating, sighing, or lamenting:

For singing Art, the Germans are said to houle, the Flemmings to sing the Spaniards to sob, the French to deskant, the Italians to bleate. Or otherwise: the Italians to lament, the Germans to crie, the French to sing: or otherwise. The Spaniards weep, the Italians sigh, the English bleate like Goats, the Germans bellow, the French sing.[20]

Aphorisms of this kind were not unique. The seventeenth-century German polymath and music theorist Athanasius Kircher, for example, quoted a similar passage, which he called an “old saying,” in his Musurgia universalis, vol. 1, book 7 (Rome: Ludovico Grignani, 1650): “The Italians bleat, the Spanish bark, the Germans bellow, the French warble.” Kircher explained that this Italian vocal “bleating” had not a glum but a comedic effect.[21] The term “bleating” could refer to the sound of a specific Italian vocal ornament popular at that time, the trillo.

2.5 In this period, melancholy was widely considered a musical style as well as a physio-psychological condition, both of which were associated with musical genius. Early moderns typically linked melancholy to an excess of black bile in the body and to a state of cosmic, spiritual misalignment. Many seventeenth-century thinkers believed that this mental, physical, and spiritual affliction could be remedied through music making, as musicking restored harmony between imbalanced humors and spirits and between body and soul.[22] Read in this context, Raymond’s and Evelyn’s identification of an Italian “addiction” to music (see par. 2.1) approaches real medical diagnosis, while Lassels’s description of Italian musicality pathologizes cultural difference by invoking an older geohumoral interpretation of musical melancholia as phenotypically linked to ethnicity and the Mediterranean climate. Early European ethnological writers theorized that melancholia was a side effect of African blackness, induced partly by the hot, dry climate of the Southern hemisphere. It was thought that the farther southward Northern Europeans traveled, the more susceptible they became to losing their “native” sanguine and phlegmatic temperaments. English authors responded to this idea with ambivalence, as the cultural adoption of melancholy was deeply in vogue but had long been theorized as a white bodily absorption of southern blackness, or of a racialized melancholic “darkness.” These harmful notions were foundational to climate determinism, an early form of scientific racism.[23]

2.6 According to Moryson, Venice in particular had always reigned supreme in “the Art of Musick,” and never more than at the turn of the seventeenth century:

The Milanesi are said to excel in the study of the Civill Law, the Florentines in natural Philosophy, the Calabrians in the Greeke tongue, the Neapolitans in the Hetrurian [ancient Etruscan] or Tuscane tongue, those of Lucca in Divinitie. those of Bologna in the Mathematicks, the Venetians in Musick, those of Ferraria, Paduoa and Salernum in Phisick, those of Sienna in Logick, those of Perusium in the Canon Law of the Popes, and those of Pavia in Sophistrie.[24]

Moryson stressed that Venetians excelled in “making lutes, Organs, and other Instruments of musicke.”[25] And yet, he clarified, Venetian expertise was not to be found “in light tunnes and hard striking of the stringes, (which they dislike),” nor was it in itinerant companies of fiddlers, as the Republic had “none or very fewe single men of small skill.” Rather, the Venetians preferred “Consortes of graue soleme Musicke.” Their sweet and soft “touching of the stringes” was often paired “with winde Instruments, and most pleasant voyces of boyes and men.…”[26]

2.7 Given these declarations about the excellence of Venetian instrument making and the known demand for Italian singer-lutenists and Venetian-made lutes in England at that time, it is only fitting that two English writers compared the lagoon’s topography and watercraft to musical instruments.[27] After scaling the campanile in Piazza San Marco, Evelyn expressed his surprise at the vast “sight of this Mira⟨c⟩ulous Cittie which lies in the boosome of the sea in the shape of a Lute….”[28] When the future politician, military officer, and colonial commissioner Bullen Reymes visited Venice about a decade earlier in 1633, he wrote in his personal diary that he had ridden “in a small boat in the shape of a lute, where I played a lute.…” Reymes had just bought that lute in Venice. He was also a guitarist, pochette player, and composer who spent a significant amount of time hearing, studying, and making music throughout the Republic. He kept a detailed trilingual diary of his daily experiences there throughout the 1630s.[29]

3. Catholic Institutions and Ceremonial

3.1 British travel accounts demonstrate a conflicted response to Venetian sacred music. Their authors were dazzled and yet, at times, suspicious. Not only did British spectator-auditors find themselves immersed in an urban landscape boasting a remarkably high number of first-rate sacred musical institutions, but many of the instruments and voices that they heard––particularly of women and castrati––were also new to the world of post-Reformation church music in England. Even if Protestant travelers held onto their faith, they were easily spellbound by the Catholic sonic world.[30] Raymond professed that the high quality of Venetian music was his primary reason for visiting churches in the Republic.[31] Most English travelers in Venice were especially awestruck by music at Saint Mark’s Basilica, the Scuole Grandi, and the Ospedali Grandi.

3.2 The exceptional string, wind, and vocal talents of musicians in Venice, Moryson explained, had a strong spiritual effect on listeners, whether in public or private settings. Rapturous consort music was usually performed in churches and seemed “to rauish the hearers spiritt from his body,” elevating the affections and thus intensifying the religious devotion of the Republic’s Catholic churchgoers.[32] On Sundays and feast days throughout all of Italy, Moryson wrote, one could hear “consortes of excelent musicke, both lowed and still Instruments and voyces” as well as processions with “Images caryed and Priests singing before them.…”[33] The anonymous author of British Library, Sloane MS 682 (1610)––possibly Thomas Berkeley or another member of his travel party––stated that on feast days Venetian churches resounded with “all Musicke as Voices Hoboies Cornets Shackybouts Consort and Vialls.…”[34]

3.3 Moryson, a Protestant, was nevertheless wary of this enchanting music and did not always write so favorably about Catholic processions in Venice, which featured

… Companyes of Prists and Fryers of Religious Orders, carrying with them the Crosse and banners of the Images of Saynts, and singing all the way they march, as likewise in the attendance of the bretheren of the Schooles, espetially of the six great Schooles.…[35]

Moryson particularly disapproved of the Republic’s decadent Corpus Christi processions, in which he witnessed “the Patriark singing Masse.” The whole affair, in his opinion, was “performed as they say with much humility, but it may be better sayd with grosse Idolatry.”[36] He viewed all of Italy as saturated with excessive religious ceremony:

… in sprincklings of holy water, hallowing of Churches, Chappells, Alters, and Bells, in Baptising of Bells, in Processons vpon the Saynts festiuall dayes, at the Churches dedicated to them, wherein the Prists with lighted tapers, with banners, and singing, and Trumpitts, carye the Saynts Images about the Church and parish to be adored by the people.[37]

3.4 Moryson described San Marco in detail, as did another professional English travel writer, Thomas Coryat, who visited Venice in 1608 and later published a famous account of his sojourn there.[38] Both Moryson and Coryat mentioned a “singers pulpit” in the chancel of San Marco “where the Musitians sing at solemne Feasts” and relics and newly elected doges were displayed before the congregation.[39] Coryat described the pulpit as “another faire round thing … wherein the Singing men do sing upon Sundaies and festivall daies.”[40] Moryson attended a Christmas Eve Vespers service there, “song with most exquisite musicke both of Instruments and voyses,” as well as a Mass before midnight.[41] At San Marco on the Feast of the Assumption, Coryat heard “much good musicke,” “but especially that of a treble violl which was so excellent, that I thinke no man could surpasse it.” The service also showcased yet more sackbuts and cornets which, in Coryat’s estimation, “yeelded passing good musicke.”[42] Moryson would have heard the basilica’s music program under the direction of Baldassare Donato, while Coryat visited during the tenure of Giovanni Croce. Both foreigners likely heard elaborate polychoral and lush instrumental music.[43]

3.5 Reymes also frequented San Marco during his time in Venice. He heard Christmas Eve and Christmas services there in 1633 and watched the doge’s procession to the island of San Giorgio for the Vigil of Saint Stephen. Reymes wrote that on Christmas Eve, he “saw the ceremony where the Doge was: there were many musicians and candles.…” In this period, the basilica’s maestro di cappella, Claudio Monteverdi, was expected to compose new mass settings for annual Christmas celebrations at San Marco, for large ensembles of both singers and instrumentalists. The ducal andata across the lagoon to San Giorgio Maggiore on Christmas Day (technically the next liturgical day’s Vigil of St. Stephen) would have been a grandiose affair, accompanied by trumpets and shawms and culminating in plainchant by the church’s Benedictine monks at Vespers.[44] In 1659 the English travel diarist Francis Mortoft also visited San Marco and witnessed a grand musical procession for Good Friday:

… First went multitudes of People with great wax candles, then came 9 or 10 Priests singing in a kind of doleful manner, then followed one man which carried a Crucifix on his shoulders, after him, many Priests.[45]

3.6 Beyond the musical offerings of San Marco, Coryat was impressed to hear “much singular musicke” at the convent of San Lorenzo, notably featuring sackbuts and cornets.[46] Reymes went often to hear music at the Franciscan church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, at the Augustinian church of Santo Stefano, and at the Dominican church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo. He had the opportunity to hear Monteverdi’s compositions and musicking in multiple Venetian spaces, for example recounting on New Year’s Day 1634 that he had heard “some beautiful music by Claudio Monteverdi” at Santi Giovanni e Paolo. A few days later, he heard Mass at the church of San Zulian (or, San Giuliano), “where Monteverdi beat time” for the Feast of Saint Lorenzo Giustinian.[47] On Saint Catherine’s Day in 1633, Reymes heard “good music” (“bon musique”) at the church of Santa Caterina, and in 1636 he heard music at the nunnery of San Zaccaria for the Feast of Saint Leodegarius.[48] Robert Bargrave, an itinerant merchant who was an amateur composer, music copyist, and viol player, kept a travel diary of his visits to Venice in the 1650s and was deeply impressed by what he heard at the Ospedali dei Mendicanti and della Pietà. On his visit to the Ospedale della Pietà in 1655, he heard a particularly dynamic performance by what he described as a famous singing nun. Bargrave penned in both prose and music notation a detailed record of her expressive vocal ornamentation, which included cascate, intonazioni, portamenti di voce, trills, and echo effects.[49]

3.7 Coryat had the great pleasure of attending multiple musical performances at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco for the Feast of Saint Roch in August 1608. He declared it to be the best music that he had ever heard and repeatedly lauded its splendor. Evoking Moryson’s general description of Venetian consort music, Coryat’s account gushes that the music at San Rocco was both ravishing and stupefying to listeners who had never heard anything like it. He too had been “rapt up with Saint Paul into the third heaven.” Although Coryat did not name any of the performers himself, present-day scholars have determined that he heard an ensemble of twenty male singers under the direction of Bortolo Morosini, along with sixteen instrumentalists led by Zuanne Bassani and Niccolò dalla Casa. The instrumental group––comprising cornets, sackbuts, violins, violoni, and theorbos––was joined by no fewer than seven organists: Giambattista Grillo, the organist of Santi Giovanni e Paolo, and five others provided by Giovanni Gabrieli (the scuola’s regular organist). Coryat was especially bowled over by the event’s talented vocal soloists, Bartolomeo Barbarino, “Giulio da Padoa,” Mattia Fernando, and Vido Rovetta. At least a couple of the singers appear to have accompanied themselves on theorbos and violins. The music might have included polychoral and instrumental works by Monteverdi, Giovanni Gabrieli, Alessandro Grandi, and Giovanni Rovetta. One piece could have been Gabrieli’s Sonata a tre from his Canzoni et sonate (Venice: Gardano, 1615).[50] In 1636 Reymes also reported that he “went morning and evining to the fest of St. Roche wher I heard very good musique.”[51]

3.8 Moryson proclaimed that Roman and Venetian ceremonials were the most frequent and grandiose in the world.[52] He described many of them in detail, particularly the Marriage of the Sea ceremony and other Ascension Day festivities (called the Sensa in Venetian dialect). Moryson and his fellow British travel writers were generally astounded by the feast’s musical magnificence. Spectator-auditors attending these Sensa events would have heard a rich variety of vocal and instrumental music in different settings. First, Moryson explained, during the andata in trionfo,

… 8. standards are carryed, then followe six siluer Trompitts, then march two by two the Dukes officers … being all 50. in number.… Then follow the waytes of the Citty, and the Drumms, attyred in Red, sounding and beating all the way.[53]

Fraser, who saw the Sensa when he visited Venice in 1659, explained, “At the Sound of a Trumpet” the doge would descend from his palace and would be carried on a throne to the other end of the piazza to board his stately bucentaur, or ceremonial barge. Fraser mentioned that upon this grand barge was also “a Cabin, for the Músitians.”[54] The doge would then embark, surrounded by drums, silver trumpets, and, as mentioned by more than one travel writer, a number of gilt statues evidently representing enslaved laborers.[55] Coryat proclaimed the bucentaur’s sculptures to be “a wondrous ornament to the galley.” The barge’s collection of statues also included winged lions and Skanderbeg, who, in Coryat’s words, had led the Venetian military in many “glorious victories” against the Ottoman Empire.[56] The politician, soldier, and antiquary Richard Symonds also witnessed the Sensa and wrote of the bucentaur, “The upper end or prova is supported by 8 Slaves cutt in Wood & guilt.… Below [are] the Rowers in a Roome underneath….”[57]

3.9 Lassels recalled that on Ascension Day, the unfree rowers of the doge’s “noble galley” below deck were “placed underneath and unseene; but their great oares (twenty on a side) moveing all at once, [made] it steere maiestically.”[58] Once the bucentaur’s anchor was weighed, Lassels explained, the ship’s rowers moved in sync with the music onboard: “the slaves being warned by the Captains whistle and the sound of trumpets, begin to strike all at once with their oares.…”[59] Fraser similarly wrote that the barge would take off “at the Sound of a Trumpet,” at which point twenty oars would begin to row “all so uniformly” and majestically.[60] (See Fig. 2.) Then, according to Lassels, the ship would set off on its ceremonial excursion “gravely and slowly to the tune of trumpets and the musick of the voyces which sing chearfull Hymeneal tunes.”[61] “[T]hus they steere for two miles upon the Laguna, while the musick plays, and sings Epithalaiums all the way long, and makes Neptune jealous to heare Hymen called upon in his dominions.”[62] Fraser’s account also mentions “Musitians & Trumpeters” on the water and raves that the “Melodius harmony of Musickall Instruments, & vocall tunes. would ravish the Stupidest fancie. all the belles Ringing musicall cheimes.…”[63]

3.10 As Bargrave put it in 1655, the doge’s galley was

… lanchd to Seae; a vessell most richly adornd, and rowed by a multitude of men on the lower Deck unseen, whiles the upper Deck is covred, as it were, with a rich Canopy of Gold, borne (towarde the Sterne) upon the Shoulders of Slaves, most artificially resembled in Statutes [statues], which lively imitate the paine they suffer under the burden: and under this Canopy is carrièd the Dóge … and the whole Senate of Venice, as farr as the barr of Lio [Lido], attended by innumerable Piotta’s and Gondola’s, filld with Gallants and Ladies, some in Masquera; some barefaced, with litle Companies of rare Trumpetts and Drummes.[64]

The ship in question, perhaps except in Moryson’s account, would have been a new bucentaur completed in 1606 by Marcantonio and Agostino Vanini. It was rowed by forty-two oarsmen and apparently featured multiple telamons holding up a canopy (Fig. 3), which, according to the poet Ferdinando Donno, depicted Black subjects (“negri di viso”).[65]

3.11 It is not known who exactly would have manned the bucentaur on these occasions. The vessel’s oarsmen could have been free men hired for this specific event, or they might have indeed been interned. Although the Venetian navy had famously depended on free galley rowers before the sixteenth century, by the Stuart period the Republic’s galleys had largely been converted into galee sforzate, or “forced galleys,” powered by Ottoman prisoners of war, incarcerated debtors, and other criminal convicts (condannati).[66] Beyond galley internment, the Venetian empire had a long history of slavery, no doubt well known to British visitors. Since the Medieval period, Venice had enslaved peoples from Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the African continent to work as boatmen and galley rowers, in domestic service, on farms in the Veneto, or on sugar plantations in Crete and Cyprus. Venetian traders were also major suppliers of slave labor for both Muslim and Christian markets far beyond the peninsula.[67] For early modern British travelers, the Mediterranean region was often their first significant introduction to slavery, either as participants in slaving voyages, beneficiaries of local slave labor, or themselves captives of the Ottoman Empire. These experiences shaped England’s rising pursuit of the Atlantic slave trade.[68]

3.12 By the Stuart century, British visitors might have been primed to look for the bucentaur’s statues and rowers. Whether or not the barge’s oarsmen were enslaved, Lassels chose to describe them as such, and British travel accounts rarely isolate the Sensa’s music from mention of slavery. The interest of these authors in the subject is unsurprising, as England was then asserting an increasingly aggressive presence in the Atlantic slave trade and shared a rivalry with the Ottoman Empire. Collectively, these British travel accounts illustrate an event in which the sights and sounds of the bucentaur operated in tandem to convey the might of the Venetian navy through musically choreographed subjugation of the subaltern. Past scholarship on the Marriage of the Sea ceremony has shared almost nothing about the laborers who rowed the doge’s glittering vessel in time to its sumptuous music, a historiographical erasure perhaps inherited from Italian primary sources.[69] In recent years, however, early modern galeotti have garnered much musicological interest. Nathan Reeves, for example, has shown that galley laborers in other regions of early modern Italy, such as Spanish Naples, were also subjected to this bodily entrainment of syncing their rowing movements to the musical rhythm of drums and trumpets.[70]

3.13 Whether or not they explicitly mentioned slavery on Ascension Day, most British travel writers agreed that the bucentaur and its music were magnificent to behold. Moryson wrote that the doge and senate boarded the bucentaur “with greate pompe and solemnity, and with loude instruments of musick,” and that the galley’s procession was “attended by the exquisite musicke of St. Marke, and with a strange number of Gondole wherein the Cittizens and strangers passe to see the pompe….”[71] The traveling merchant and amateur lutenist Peter Mundy was also impressed when he saw the vessel in July 1620. His diary explains that after the day’s metaphorical marriage ceremony, joining Venice to the sea, the doge and Venetian nobility would “retourne with the greatest musicke and Triumph they can Invent, there goeinge in Company diverse other vessels to assist the Marriage, all very gallantly set forth.”[72] Lassels likewise exclaimed:

I confesse, of all the sights that I ever saw, nothing ever appeared to me more maiesticall, then … to see the Sea covered with such rich boates (a thousand in number) all waiting upon the Bucentauro, as if Neptune himself had been going to be marryed; and all echoing with the fanfarres of trumpets.[73]

3.14 Evelyn described the ceremony as a fusion of musical and military sounds. Like his fellow travelers, he was enthralled by the

… gloriously painted, carved & gilded Bucentoro, invirond & follow’d by innumerable Gallys, Gundolas, & boates filled with Spectators, some dressed in Masqu⟨e⟩rade, Trumpets, musique, & Canons, filling the whole aire with din: Thus having rowed out about a league into the Gulph, the Duke at the prow casts into the Sea a Gold ring, & Cup, at which a loud acclamation is Echod by the greate Guns of the Arsenale, and at the Liddo …[74]

One anonymous British author similarly described the doge’s galley circa 1610 as outfitted with “[a]ll kiend of Musicke: and Instriments of Warr.…”[75] Bargrave also mentioned hearing guns, fireworks, and the “glorious Ascension Faire upon Saint Markes Place,” which featured mountebanks, jugglers, rope dancers, “monsters and other novalties.”[76]

3.15 Once the ceremony had ended (with, as Fraser wrote, “sound of trumpet”), Lassels recounted that the doge and his train continued on to “a monastery in a Little Iland hard by [San Nicolò al Lido]” where “he heares high Masse sung with excellent musick.” After dinner Lassels and his travel party proceeded to the island of Murano, where the English priest saw smaller Venetian boats (or “piottas”) racing up and down the island’s central canal:

… with their trompeters in each Piotta sounding several tunes and denounceing to one an other an airy warre, as the brawny leggd watermen striving to outrow one another denounce a watery one.[77]

3.16 It has been well established that early modern Venetian musical pageantry operated as state propaganda, perpetuating the so-called “myth of Venice” that distinguished the Serene Republic as an exceptionally powerful, harmonious, and well-functioning maritime empire. The Sensa was a rite of state possession that symbolically asserted Venetian dominion over international trade and the Adriatic.[78] It appears that for most British travelers to Venice, the ceremony’s musical majesty was inextricable from its robust demonstration of the Republic’s military strength. In these accounts, resplendent vocal and instrumental music resounds alongside cannons, guns, and statues of war heroes and the enslaved; galley oars move in time to the bucentaur’s music; and at day’s end, an “airy warre” on Murano between trumpeters on racing boats mimics real naval conflict.

4. “Instriments”

4.1 Organs, bells, and other musical instruments make numerous appearances in British travel accounts of Venice. Generally, these items are presented not primarily as sources of musical sound but as decorations, commodities, inventions, novelties, weapons, or tools of state ritual. In some cases, these various functions overlapped: Venetian “Instriments of Warr” could uncannily resemble instruments of music, and instruments of music could become sites of great violence. In and beyond British accounts of the Sensa, the connections drawn by some British travel writers between weaponry and instruments cast both as formidable Venetian technologies of empire.

4.2 In the armory of the doge’s palace, Lassels saw “The Divels organs,” a leather trunk filled with a dozen pistol barrels that would supposedly shoot every which way when the trunk was unlocked, assassinating everyone in the room. As Lassels wrote, “The holes thorough the sides of the trunck shew the Divelish effect of this invention, therefor called the Divels organ, because the pistol barrels lye in it in ordre like organ pipes.”[79] The sculptor and mason Nicholas Stone the Younger, who visited Venice in the 1630s and 1640s, mentioned the weapon in his diary as well, though he specified that it was not for practical use: “I have sene diuers peeces of artylyrye with three nossells, euen to seuen, the wch they cale organes, instruments made more for magnificence than usse and seruice of warr.”[80]

4.3 Coryat recounted one particularly violent musical accident atop Saint Mark’s Clocktower, where two fifteenth-century bronze mechanical figures of what Coryat called “wilde men” (most likely the work of Antonio Rizzo) had been constructed to periodically strike the clock’s bell. Coryat explained that although he had not seen this tragedy himself, several of his countrymen had witnessed it and urged him to record it in his diary:

… A certaine fellow that had the charge to looke to the clocke, was very busie about the bell, according to his usuall custome every day, to the end to amend something in it that was amisse. But in the meane time one of those wilde men that at the quarters of the howers doe use to strike the bell, strooke the man in the head with his brasen hammer, giving him such a violent blow, that therewith he fel down dead presently in the place, and never spake more.[81]

Evelyn narrated this same story over thirty years later, claiming that “an honest merchant” in the city had told him that

… the fellow who kept the Clock, struck with his hammer so forcably, as he was stooping his head neere the bell to mend something amisse, at the instant of striking, that being stunn’d, he reel’d over the battlements, & brake his neck.[82]

4.4 In an inventory that Coryat published of important objects and institutions in Venice, he counted “two hundred Churches in which are one hundred forty three paire of Organs.”[83] No doubt building on this quantitative tradition, the politician John Reresby, who played the lute and guitar and chronicled his travels to Venice in the 1650s, listed the exact same number of organs in Venice nearly fifty years later.[84] Moryson mentioned many of these, notably the organs in San Marco, “said to be the Worke of a most skilfull Artificer.”[85] Coryat described these instruments in greater detail, writing that on both sides of the choir he saw

… two exceeding faire payre of Organes, whose pipes are silver, especially those on the left hand as you come in from the body of the Church, having the brasen winged Lyon of S. Marks on the top, and the images of two Angels at the sides: under them this is written in faire golden letters, Hoc rarissimum opus Urbanus Venetus F.[86]

4.5 Moryson climbed to the top of the campanile in San Marco and reported in a consistently empirical manner that the tower

… beares foure great bels, whereof the greater called La Trottiera, is rung every day at noone, and when the Gentlemen meet in the Senate with like occasions: but when a new Pope or Duke is made, all the bels are rung, and the steeple is set round about with waxe candles burning.[87]

4.6 When Moryson and his travel party visited the Vendramin collection, they were shown “a paire of Organs having strange varieties of sounds.”[88] On Murano Lassels saw yet another curious “Organ in glasse three cubits high, so justly contrived, that by blowing into it, and touching the stopps it sounded musically.”[89] When Fraser visited Murano he saw glass “floútes” and glass sculptures of “a fidler wt his fidle or violin,” “a bass viol Consort,” and “a case of Organes. wch. as you Could judge gave Musicall sound.…”[90] Read alongside other British travel writing on Venetian music and commerce, these descriptions of tiny flutes, organs, and other glass musical sculptures suggest a British view of the Republic’s lucrative glass trade and instrument production as two interlinked commercial markets. Venetian-made glass and musical instruments were both desirable commodities in England, and British visitors certainly did more than admire them. By the end of the seventeenth century, the European glass trade was dominated by two men: the Venetian Alvise Morelli and an Englishman, George Ravenscroft. It was Ravenscroft’s own sojourn in Venice that enabled him to develop the capital, entrepreneurship, and manufacturing knowledge necessary for infiltrating international glass markets.[91]

5. Jewish and Greek Orthodox Rites

5.1 Beyond climbing the campanile, observing the Sensa, and visiting San Marco and the ducal armory, British travelers usually stopped at Venetian synagogues and Greek Orthodox services at the church of San Giorgio dei Greci. British tourists would have experienced both as a novelty, as Jewish worshippers were not legally permitted to practice their faith in England until the 1650s and there was no Greek Orthodox church in London until after Restoration. Visiting new cities like Venice brought many British travelers into contact with Jewish communities for the first time.[92] Gathering information about Greek and Jewish minorities in early modern Venice was no frivolous pursuit: British trade alliances with both communities in the Republic supported England’s entry into Mediterranean commercial networks.[93] Most British commentary on Greek Orthodox and Jewish rites can be interpreted as an early Orientalizing, proto-ethnological exercise in comparative assessment of diverse musical traditions. Coryat’s harsh opinions in particular relied upon overt anti-Judaism and xenophobia to assert the superiority of his own English Protestant identity.

5.2 According to Coryat’s derisive description of music at San Giorgio, when the congregation sang “to answere the Priest, they have one kinde of gesture, which seemeth to me both very unseemely and ridiculous. For they wagge their hands up and downe very often.”[94] He continued:

The Priest … saith service in a private Chappell, before whom most commonly there is a Taffata curtaine drawne at the dore, that the people may not see him, yet sometimes he removes it againe. When the Grecians in the body of the Church answere the Priest, a little Greekish boy in a short blacke gowne goeth oftentimes from one side of the Church, where they sit, to the other, holding a Bible in his hand, unto whom the Grecians sing by turnes, sometimes one at a time, sometimes three or foure.…[95]

5.3 The nuances of the Greek Orthodox liturgy were lost on Coryat, who had no musical details to share beyond mentioning cheironomy and responsorial, antiphonal singing.[96] The consensus among a handful of other British writers was that Byzantine rites performed at San Giorgio differed relatively little from those of the Catholic Church.[97] Approaching the San Giorgio services from a Catholic ecclesiastical perspective, Lassels was much less critical than Coryat and made an effort to learn more about what he heard. He found “an understanding Grecian to tell me in particular all the Ceremonies and their meaning; and in conclusion I found them saying masse perfectly.” Lassels comprehended that

… he that sung the Masse was a Bishop clad in his Pontificalibus with his miter upon his head, and his crosier staff in his hand; whiles the Deacon that sung the ghospel, and the subdeacon that sung the Epistle were clad in Tunicks as the Roman fashion is.[98]

5.4 Much has been written about Coryat’s recorded visit to a Venetian synagogue. The first author known to have penned the word “ghetto” in English, Coryat disparagingly portrayed the service as a cacophonous, disorderly affair, confirming his own preconceived stereotypes and deep-rooted theological prejudices. Coryat’s descriptions of the cantor’s “exceeding loud yaling, undecent roaring, and as it were a beastly bellowing” echo his accounts of a “noisy” neighborhood beyond the walls of the synagogue. Coryat also mentioned a group of “Clerkes,” who “do roare with him, but so that his voyce … drowneth all the rest.”[99] Scholars have analyzed Coryat’s comments as a representation of broader English disdain for Jewish “noise pollution” and negative impressions of Venice as a declining republic overrun with undesirable sounds and peoples.[100] Early modern Christian observers often described the chanting of Jewish communities in Europe in similar terms, contrasting the perceived coarseness of participatory Jewish cantillation with what they heard as more orderly, refined Christian musical repertoires.[101] In this and many other ways, Coryat’s travel text persistently differentiates his own English Protestant ethical “seriousness” from unfamiliar religious and ethnic communities that he encountered abroad.[102]

6. Secular Revelries

6.1 British travel writers frequently shared their recollections of Venetian opera, theatre, Carnival, and other secular musical events. During the Feast of Saint Martin throughout Italy, Moryson noted “the boyes singing in the streetes in Italian, long liue St. Martin with his cup of wyne and his goose rost, giue me a bitt my host.…”[103] He similarly shared that around All Saints’ Day every year, local Venetian artisans “haue a Feast, wherein they weare feathers, and haue Trumpitts continually sounding, and during the tyme of this worke all the shops about Rialto resounde with the blowing thereof.”[104] Moryson also wrote that after aristocratic weddings in Venice, guests would be invited to the home of the bride’s parents, where the bride would be escorted around the room “with the sounde of Drumms, Trumpitts, and other musicall Instruments, going in a Comely measure of daunsing, and so often bending the body to the guests as shee passeth.…”[105] Contemporary Italian accounts of this tradition explain that during a typical Venetian wedding reception, or parentado, a young bride would be led about the room in a circle by her dance master. The newlywed woman would then perform a few dances for her friends and family to the sounds of sundry musical instruments.[106] In describing such private forms of Venetian musicking, Moryson’s travelogue invited his readers at home to vicariously enter the innermost circles of the Republic’s social life.

6.2 While Carnival celebrations and other comparable festivities did occur in England, they were nowhere near the scale of what British travelers experienced in Italy. Writing about Carnival and the carnivalesque in this period served as a vehicle for broader social, political, and economic commentary about the rise of capitalism and republicanism in Britain.[107] Visiting foreign Catholic locales where Carnival merriments reached their highest levels of extravagance enabled many travel diarists to contribute to these discussions in unique ways, in particular by recording their proto-ethnological perspectives on the sociopolitical functions of Carnival in different cultural contexts. Lassels portrayed these musical amusements as a means of maintaining the equilibrium of the Italian “midling humour.” He declared that the Italian “gravity is not without some fire, nor their levity without some fleame.” Italians were “as apish as any nation in the world, under a visard in their Comedies and Carnevals, and as serious againe when thats pluckt off.”[108] In Lassels’s eyes, periodically indulging these riotous tendencies allowed Italians to succeed in more serious political endeavors and thus maintain state order despite their melancholic affliction: “all this is allowed the Italians that they may give a little vent to their spirits which have been stifled for a whole yeare, and are ready to choke with gravity and melancholy….”[109] Reresby similarly theorized that the Venetian Carnival featured “almost as many dresses and extravagances as men, as if the folly of this nation reserved itself the rest of the year to deboard itself more violently at that time.”[110]

6.3 Moryson wrote that “[i]n generall the Italians loue not to be excluded from musicke or Comedyes.…”[111] Describing the overall Italian Carnival season, Moryson recounted that both men and women would “walke vp and downe the markett places, and some companyes leade musicke with them and table to place some Instruments in the markett places, where they play excelent musicke.”[112] He also wrote of public dances “where all that are masked may freely enter, and dance with wemen there assembled and he that danseth at the ende of his danse payes the musitians an ordinary rate of small mony.”[113] Reymes was a constant Carnival reveler. He regularly went to see comedies, masqueraded throughout the city, and partook in other public musical diversions.[114] Evelyn participated in “the folly & madnesse of the Carnevall” in Venice as well, with

… the Women, Men & persons of all Conditions disguising themselves in antique dresses, & extravagant Musique & a thousand gambols, & traversing the streetes from house to house, all places being then accessible, & free to enter.…[115]

6.4 Reresby also seems to have gleefully participated in such amusements. He explained that in order to “act the Frenchman” during Carnival, Venetians went about “frisking to the sound of a guitar and a pair of tongs, with a great many yards of cut paper of several colours, for ribbons, and bells for buttons.”[116] Then, Reresby continued, some Venetians “dance antiques, where they meet with convenient room, dressed like satyrs, apes, savages, to excellent concerts of music they carry with them.”[117] During one 1655 masquerade in Piazza San Marco, Reresby was attended by a young bagpiper whom he covered in so many petticoats that local listeners could only hear and not see the instrument. Curious to know the source of the foreign instrument’s sounds, excited Venetian crowds began to follow the two and attempted to unclothe the bagpiper.[118]

6.5 When Bargrave’s ship visited Venice again in 1656, it was quarantined for forty-three days after one crewmember unsuccessfully tried to smuggle wool––then thought to be a major carrier of contagion––onto Venetian soil. Bargrave and his crew were finally permitted to disembark in February 1656, at which point Carnival celebrations had only just commenced and were a much welcome respite from his troubles.[119] The city was bursting with the sounds of fireworks and dramatic entertainments. As Bargrave recorded:

At length our Penance expir’d, and our full Lent of Solitude at Seae, brake out into a glad Carnevale on Shoar; which was but newly begun when our Prattick was granted; & seemd so much the more delightfull, by how much our Restraint had been more hard and tedious: Nay at the first it seemd rather an Aparition then a reall thing; or as if the world was in a Frensy; while every man or woman appeared some new Creature, in as many shapes as there were persons: theyr Habits were from the extremitie of the Rich and Gallant, to the extravagance of base and ragged; some here dancing, some there singing, and others drolling.…[120]

6.6 Secular musical performances constituted a large part of the city’s daily commercial hurly-burly, whether funded by public audiences or presented as advertisement for medical wares, sex work, or other financial transactions. Venice offered ample opportunity for British travelers to see public plays and hear theatrical music. Coryat saw a comedy but thought little of its quality. In his opinion, the Venetian playhouse was “very beggarly and base in comparison to our stately Play-houses in England: neyther can their Actors compare with us for apparrell, shewes, and musicke.” He was nonetheless fascinated to see women onstage and insisted that they had performed just as well as their male counterparts.[121] Once again, Coryat here adopted a comparative and competitive tone, not only to insist on the superiority of English theatre but also to highlight an unfamiliar dramaturgical practice that had worked well; indeed, casting women would be common practice in English theatre after the Restoration. It was no coincidence that one of the most influential proponents of introducing women onto public English stages would be the playwright and theatre impresario Thomas Killigrew, who served as English ambassador to Venice in the 1650s.[122]

6.7 As for the lowest levels of the Venetian theatrical hierarchy, both Coryat and Lassels recorded their impressions of musicking mountebanks in Piazza San Marco. Moryson described a general prevalence of mountebank music throughout Italy.[123] Coryat noticed an especially high toleration of mountebanks in Venice as compared to other Italian cities.[124] As he narrated, once these “Ciarlatans” were all onstage, vocal and instrumental music would begin to play, which was but “a preamble and introduction to the ensuing matter.” The company’s leader would then proceed to open his trunk and set out his wares until the music ended. After giving a lengthy speech, “he delivereth out his commodities” to the sound of yet more music.[125] These commodities included everything from oils and medications to “amorous songs printed.”[126] Coryat remembered seeing one blind mountebank who was “noted to be a singular fellow for singing extemporall songs, and for a pretty kinde of musicke that he made with two bones betwixt his fingers.”[127] Lassels, clearly unimpressed with these trifles, mused on the strangeness of the mountebanks’ daily “new fooling” in the piazza and on the apparently ridiculous expectation that onlookers “throw them money too for such poore contentments.”[128] He wrote that every night in the summer, such “ciarlatani” worked the crowds “with their little comedies, puppet playes, songs, musick & storyes, and such like buffonnerie.”[129]

6.8 The outlandish street entertainments of these traveling snake oil salesmen combined music making with other jests in order to attract potential customers for their quack medical wares and other merchandise. Musicking also contributed to mountebank sleight-of-hand routines. Typically costumed as religious and ethnic Others, mountebank troupes sometimes marketed their products by interspersing musical performances with shocking spectacles such as fire eating, tightrope walking, parodied medical procedures, self-inflicted wounds and poisoning, and the handling of dangerous animals like venomous snakes. Both men and women in mountebank productions sang and played instruments such as flutes, lyres, and violins. As English law more strictly prohibited most street activity, such performances never took hold in Britain and so would have been a uniquely foreign experience for most British travel writers.[130]

6.9 In Coryat’s words, “amongst many other things that doe much famouse this Citie, these two sorts of people, namely the Cortezans and the Mountebanks are not the least.…”[131] Coryat’s writings about courtesans fluctuate between fascination and moral indignation, portraying the beguiling songstresses as manipulative and dangerous. (See Fig. 4.) He issued a warning to his English readers:

… [S]he will endevour to enchaunt thee partly with her melodious notes that shee warbles out upon her lute, which shee fingers with as laudable a stroake as many men that are excellent professors in the noble science of Musicke; and partly with that heart-tempting harmony of her voice.[132]

6.10 Multiple authors have analyzed this representation of Italian courtesans as bewitching seductresses, interpreting Coryat’s words as a conflicted moralizing treatise betraying a broader cultural discomfort about the dangers of English exposure to a supposedly degenerate Venetian state that vacillated between sophistication and depravity.[133] Musicking courtesans represented a feminized, sexualized, Catholic decadence that threatened the moral health of English travelers, as evidenced by Coryat’s didactic tone and erotic double-entendres. It was a well-established European trope that Italian courtesans were sinister sirens whose entrancing music and seductive powers could unravel an unwitting male aristocrat’s reputation and drain him of his wealth. British travelers determined their own role within global religiopolitical hierarchies through the lens of sexuality; they often criticized the power structures of Catholic Europe by condemning its licentiousness and perversity, establishing a moral high ground for themselves in spaces where they were the minority. In early modern English literature, Italy was usually coded as feminine, while England typically took on a more masculine characterization. English authors tended to portray Italy as a weakened and morally corrupt land that had abdicated its status as a world power, leaving a void to be filled by the emerging British empire.[134]

6.11 Reymes, by the 1630s, seems to have been unconcerned by the alleged lure of the Italian courtesan’s captivating song. He and the English ambassador to Venice, Basil Feilding, Second Earl of Denbigh, spent multiple evenings in the homes of musically inclined local women who were presumably courtesans: at one point, Reymes heard a woman named “Felicina” sing, and another night he visited a certain “Paulina” and “heard her playe one [on] the vergingles [virginals] and sing.”[135] Reymes had a chance to hear other women in Venetian society perform music as well. One day in 1636, he and Feilding went to “Sigr de la Galles house wher we heard his wife sing. and I playd on the lute.”[136] About a month later, he wrote, “I fidled, I went after dinner with my lords to Torcelle. where we heard som weomen sing and play on the lute.”[137] Evelyn noted that he had also crossed paths with some musicking Venetian women in public, though he did not specify whether the women themselves were singing or playing instruments: on his return to Venice from Murano, he “met several Gudolas [sic] full of Venetian Ladys, who come thus far in fine weather to take the aire, with Musique & other refreshments.”[138]

6.12 Apropos of singing women, most known British travelers to Venice during the British Civil War and Interregnum passed their time hearing operas. This would have been a rare opportunity, since public theatres remained closed in England until the Restoration. The reflections of these writers on opera, as with sacred music, convey more than a detached appreciation for a Venetian art form: opera was regarded in Britain as an impressive Venetian commodity and technology. It was highly coveted and was eventually imported to Stuart England by Killigrew and his contemporaries, a highly political process contingent upon mercantile modes of transnational exchange.[139]

6.13 Reresby wrote that the Venetians celebrated Carnival “with stage plays, indeed no better than farces; [and] operas, which are usually tragedies, sung in music, and much advantaged by variety of scenes and machines.…”[140] Raymond, Evelyn, and Bargrave were especially fascinated by castrati. Raymond exclaimed that the Italian addiction to vocal music was so strong “that great Persons keep their Castrati viz. Eunuch’s whose throates and complexions scandalize their breeches.”[141] In June 1645 Evelyn heard Giovanni Rovetta’s Ercole in Lidia and raved about the opulent production’s magnificence.[142] He lauded the opera’s vocalists, instrumentalists, machinery, and scenery, describing what he had heard as “Recitative Music.” Among his favorite singers were the soprano Anna Renzi, an unnamed castrato, and an unidentified Genoese bass.[143] When Evelyn returned to Venice in 1646, he saw three more operas and once again praised the vocal and instrumental talent that he had heard. These operas might have been Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea and Francesco Cavalli’s La prosperità infelice di Giulio Cesare dittatore. So strong was Evelyn’s admiration for Renzi that he invited her to dinner. She attended, along with a castrato, and entertained her hosts by singing with a harpsichord. The English consul in Venice later welcomed Evelyn to his home to hear yet another private performance by “the Genòeze, the most celebrated base in Italy, who was of the late Opera.…”[144] Bargrave was also taken with “theyr Operas, (or Playes) represented in rare musick from the beginning to the end, by Select Eunuchs and women.”[145] He praised the richness of Venetian operatic costuming, scenery, machinery, and dances. In the Carnival season of 1656, Bargrave became so infatuated with Francesco Cavalli’s L’Erismena that he saw it sixteen times and would later copy his own English version of the score.[146] Bargrave’s adoration of the opera was probably made all the more fanatical by his recent emancipation from cabin fever.

6.14 Evelyn’s inventory of collected music books mentions two 1646 collections of “Recitatives from ye opera at Venice” and “Some Excellent Compositions of the greate Masters of the Opera at Venice.” It also includes many volumes that appear to have been purchased during his time in Venice, including a 1589 Venetian print of madrigals for four voices by Jacques Arcadelt, a 1600 Venetian print of Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi’s Balletti a cinque voci, and a 1600 print of Vincenzo dal Pozzo’s madrigals, probably his Il primo libro de madrigali a quattro voci, con un dialogo a otto (Venice: Ricciardo Amadino, 1600).[147] Richard Symonds similarly purchased “2 bookes of Songs” in Venice, which contained repertoires by Monteverdi and Orazio Tarditi. Symonds visited Venice while on a long tour of the Continent between 1649 and 1651. He kept meticulous notebooks about his travels and studied at the University of Padua. He was almost certainly a theorbist; he owned multiple theorbos and carried at least one with him while traveling.[148] Many other British travelers to Venice in this period bought a high volume of printed Italian music.[149]

7. Conclusions

7.1 This case study on foreign travelers to Venice is a survey of how several different English and Scottish chroniclers represented and responded to musical activity in the Serene Republic. More than just a motley accumulation of entertaining stories, this collection of early Stuart travel accounts provides a foundation for better understanding how musical exchange between England and Venice figured into broader cultural, diplomatic, commercial, and confessional relations between both polities during a critical period of their heightened interaction. During this boom of British travel to the Continent thanks to improved international relations, music in Venice was ripe for British observation, classification, comparison, and consumption. Taken together, these Stuart accounts of foreign musical practices in Venice communicate a British impression of the Republic as an exceptionally musical maritime empire of enviable naval strength and technological and commercial prowess. More than that, Venice was for these travelers a cosmopolitan metropolis that opened England’s transalpine window into the Eastern Mediterranean and wider world.

7.2 This portrayal of Venice perhaps explains why English intelligence operatives attended so carefully to musical events in their reports on Venice, why Stuart emissaries in the Republic regularly engaged with Venetian music, and why itinerant British merchants frequently made and heard music while in Venice—to say nothing of how cultural stereotypes about Italian musicality may have informed detrimental theories of biologically determined ethnic and racial difference.[150] If these travel accounts represent a broader British view of Italo-Catholic music as capable of intensifying religious fervor in churchgoers, it is no wonder that choral and instrumental forces in the Anglican musical establishment expanded in an accordingly Italianate manner.[151] Many British observers were especially captivated by the multisensory marvels of Venetian nautical pageantry, and, indeed, aspects of England’s own state spectacle can be traced back to influences on the Adriatic. In John Webster’s pageant for the 1624 Lord Mayor’s Show, for example, the mythological sea nymph Thetis exclaims, “What brave Sea Musicke bids us Welcome” and declares that they must surely be in Venice witnessing the Sensa. Another character, Oceanus, replies that they are in fact in England: “Venice had neare the like.”[152]

7.3 While this assortment of Stuart travelers tended to regard Venice as a highly musical city, they of course also recounted many other musical experiences elsewhere in Italy and beyond. Lassels, for instance, asserted that Roman, not Venetian, music was “the best in the world without dispute.”[153] We have now learned somewhat more about Moryson’s lamenting, sighing, and bleating Italians, but what of his Flemish singers, French descanters, sobbing Spaniards, and crying, howling, and bellowing Germans? How do Stuart travelogues of Venice compare to British impressions of music in other lands in and out of Europe, particularly musicking in other imperial metropoles such as Constantinople?[154] Future work in this area might aim to produce a more comprehensive examination of how British travel accounts collectively described music across several different municipalities, countries, and continents. Furthermore, it will be important for future research to compare these perspectives with other, non-British views on early modern musical cultures. For the time being, I offer here but a glimpse into the possibilities of prioritizing travel documents as sources for research on the history of transnational musical encounter.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Kate van Orden, Emily Dolan, Kay Kaufman Shelemay, and Diego Pirillo for advising the doctoral research that this article elaborates. Thank you to my colleagues at the University of Cambridge, Harvard University, the Villa I Tatti, the Sapienza University of Rome, and the American Academy in Rome for also sharing their insights on this project. I am especially grateful for guidance that I was fortunate to receive from Grace Edgar, Katharine Ellis, Iain Fenlon, Beth and Jonathan Glixon, Betsy Griffith, Louise Haywood, Deborah Howard, Mary Laven, Kate Lowe, Simone Maghenzani, Nicholas McGegan, Francesco Spagnolo, Bettina Varwig, Stefano Villani, and Richard Wistreich. I am indebted to Edward Chaney for granting me access to Reymes’s travel diary, and to François-Pierre Goy for sending me scans of his own copy. Peter Davidson informed me about Fraser’s travelogue and generously shared his transcriptions of it. Thank you also to the British Library Manuscripts Reference Team for assistance in navigating these sources. This research was funded by the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies; the Renaissance Society of America; the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation; the US-Italy Fulbright Commission; the Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences; the Harvard Department of Music Ferdinand Gordon and Elizabeth Hunter Morrill Graduate Fellowship; the Paul and Andrew W. Mellon Rome Prize in Renaissance and Early Modern Studies; the Thole Research Fellowship in Music at Trinity Hall, Cambridge; and the University of Southern California Society of Fellows in the Humanities.

Figures

Fig. 1. John Evelyn, painted by Robert Walker, 1648–ca.1656. National Portrait Gallery, London. Evelyn reported sitting for the portrait in 1648; the memento mori imagery was added later.

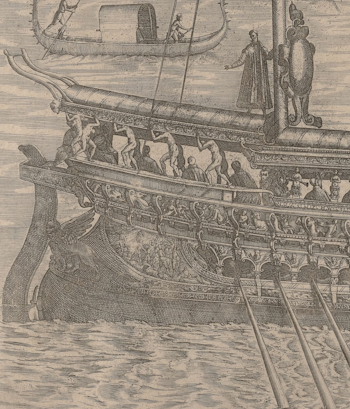

Fig. 2. “The Bucintoro [Bucentaur] at Sea with Accompanying Vessels.” Engraving in Giacomo Franco, Habiti d’huomeni et donne venetiane con la processione della Serma. Signoria et altri particolari cioè trionfi feste et cerimonie publiche della nobilissima città di Venetia (Venice: n.p., ca. 1610). Royal Academy of the Arts, London.

Fig. 3. Detail from an engraving by Justus Sadeler: Il Maraviglioso Bucintoro, nel quale il Ser.mo Principe di Venetia va solennemente il dì dell’Ascensa à sposar il mare … (Venice: n.p., ca. 1619). Cartes et plans, GE BB-246 (XIII, 42–43), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53170338m. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Fig. 4. Thomas Coryat meeting with a famous Italian courtesan, Margarita Emiliana, engraved by William Hole. In Coryat, Coryat’s Crudities: Hastily Gobled Up in Five Moneth’s Travels (London: Printed by William Stansby for Coryat, 1611), 260. Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Tables

Table 1. Quoted travelers and texts