The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 31 (2025) No. 1

Jeffrey Kurtzman and Licia Mari – Music and Worship in Mantua: Gonzaga Patronage and Monteverdi’s Role as maestro di cappella; an Investigation and a Rebuttal to Roger Bowers

Appendix 1. Critique of two articles by Roger Bowers[1]

1. Bowers’s Foundational Premise

3. The Church of Santa Barbara

4. Monteverdi as Church Musician in the Gonzaga Court, 1590–1612

5. Monteverdi’s Composition of Sacred Music, 1590–1612, as Represented by the Mass and Vespers of 1610

1. Bowers’s Foundational Premise

1.1 The driving force behind Bowers’s research and argument is the perfectly appropriate desire to know where and in what context Monteverdi’s sacred music was performed—not just that of his sole-surviving sacred print from his time in Mantua, popularly known as the Mass and Vespers of 1610 (see main text, Figs. 39, 40, 41), but his other Mantuan sacred music as well. There are, in fact, only a few documentary references to Monteverdi’s role as a sacred musician in Mantua.[2] The first is his letter of 28 November 1601 from Mantua, petitioning Duke Vincenzo, who was en route home from a military campaign against the Turks at the time of the death of maestro di cappella Benedetto Pallavicino, “to request … the title that formerly Signor Giaches [de Wert] had over the music,” and to be appointed “master of music for both the chamber and the church” (on the meaning of this sentence and Wert’s role at court, see chapter 3 below and main text, par. 11.5–11.8).[3] What is less frequently noted in citing this letter is that Monteverdi, in fulsomely obsequious language, declares that it is his duty as a devoted servant of the duke to seek “the post now vacant in this part of the Church” (emphasis ours).[4] Moreover, Monteverdi also refers earlier in the letter to his negligence were he not to show to the duke’s refined musical taste his “somewhat little worth” in motets and masses.[5] Reference to “the church” in this letter cannot mean the large palace Church of Santa Barbara, where Giovanni Gastoldi had served temporarily as an occasional substitute for maestro di cappella Giaches de Wert from at least 1582 and as Wert’s successor as maestro di cappella since at least 1588 until his death on 4 January 1609—i.e., during most of Monteverdi’s tenure at the Gonzaga court (on Wert’s role at Santa Barbara, follow the link above to the main text, par. 11.5–11.8).[6]

1.2 If Monteverdi was not responsible for music in Santa Barbara, then where was his sacred music performed? Referring to the citations of his role in charge of music “for the church,” Bowers declares:

Such references to “la chiesa” did not apply to church buildings at random. It was the duty of the personnel of the duke’s cappella, as officers of his household, to conduct divine service not at large in city churches or elsewhere, but exclusively [our emphasis] on his premises and in a physical proximity to his person sufficiently close to enable him to be in attendance at any time of his choosing.”[7]

1.3 This statement, presented as established fact with no documentation and no effort at substantiation, forms a fundamental premise of Bowers’s argument. If Monteverdi as the duke’s maestro di cappella could perform divine services only within the palace grounds, and the Church of Santa Barbara was under the direction of a different maestro, then the only other locations for such services must be the Church of Santa Croce in the corte vecchia or the several small chapels in various palace buildings.

1.4 But in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, just as today, la chiesa, or ecclesia, had multiple meanings; it could refer to a specific church, most often by name unless the immediate context made it obvious, or to the Roman Catholic Church as an institution, or to any aggregate of elements that the church as an institution comprised, including a more-or-less explicitly defined group of church buildings.[8] Nor are “church buildings at random,” the only alternative to a particular church. We could isolate as a non-random aggregate the churches of Mantua, or the churches of a specific order, or the churches visited by the duke according to contemporaneous documentation. What is problematic about Bowers positing only one possibility for the meaning of “la chiesa” is that he himself offers contradictory interpretations: (1) Bowers accurately translates the letter as referring to “the position now vacant in this branch of the Church” and correctly declares that “he [Monteverdi] expected the duke to perceive the office as primarily ecclesiastical in character”;[9] (2) he recognizes Monteverdi’s use of “la chiesa”and Vincenzo Gonzaga’s understanding of the phrase “in questa parte de la chiesa” as non-specific and general; and (3) he demands that the general interpretation of the word can only apply to ecclesiastical buildings “exclusively on his [the duke’s] premises.”[10]

1.5 That exclusivity is a basic premise of the syllogism on which Bowers’s argument about the Church of Santa Croce rests: (Premise 1) Monteverdi and the ducal cappella performed only on the palace grounds in Mantua; (Premise 2) Monteverdi and the ducal cappella had nothing to do with the Church of Santa Barbara; (Conclusion) Monteverdi’s sacred music must have been performed in the Church of Santa Croce, which must, therefore, have been large enough to host “grand liturgical occasions.” As Bowers concludes, “Santa Croce offered a building of substantial space and height, fully sufficient to have accommodated performances of the church service even in the elaborate style, enhanced with the concerted polyphony of voices and instruments, likely to have been undertaken on the grandest occasions after the accession of Vincenzo [as duke] in 1587.”[11]

1.6 But the conclusion of a simple syllogism is valid only if both premises are true and in a relationship that clearly leads to the conclusion. Yet Bowers goes on later to describe a variety of instances where Monteverdi and members of the ducal chapel performed outside the premises of the ducal palace, beginning with Monteverdi’s role as maestro di cappella on the duke’s expedition against the Turks in Hungary at the behest of the Emperor in 1595, where he and other musicians performed their duties in the presence of the duke, but not at the palace.[12] And further:

It is possible too, to discern glimpses of the cappella’s participation, at Vincenzo’s order, in the church service at venues external to the palace in Mantua. Thus when in January 1610 one don Francesco, a tenore and “musico di Sua Altezza Serenissima,” celebrated at the altar his first Mass following ordination, he was assisted by a choir of cappella singers in the ducal presence at his residence of Gazuolo.[13]

1.7 And further:

Meanwhile, under certain circumstances the cappella might also perform, in the ducal presence, at select locations within the city of Mantua. The collegiate church of Sant’Andrea served as the spiritual headquarters of Vincenzo’s chivalric Order of the Knights of Christ the Redeemer; this he had founded in May 1608, and intermittently in late spring thereafter it hosted the congregation of the current Company of Knights. It may readily be understood that on each such occasion, conducted under the personal presidency of the duke, all musical performance was contributed by his own cappella.… On the eve of Ascension Day itself there had been held in Sant’Andrea the customary observance of Solemn Vespers, in the presence of the duke and all the Knights of the Order.… That the participating musicians had been those of the ducal cappella appears to be confirmed by Campagna’s report that the service had been particularly distinguished by some “most beautiful music and new invention of Sr. Monteverdi.”[14]

1.8 We find it impossible to reconcile these and other indications of performance outside the palace grounds with Bowers’s fundamental premise that the duke’s chapel performed exclusively on the duke’s premises. Bowers’s basic syllogism leading to his conclusion about the Church of Santa Croce collapses under his own observations.

1.9 It is indeed inaccurate to claim that Monteverdi and the duke’s cappella performed services only on the duke’s premises. In fact, the only documented performance in Mantua of Monteverdi’s sacred music is the aforementioned Vespers service on the Feast of the Ascension, 1611, in the Church of Sant’Andrea, as reported by Mari and Kurtzman in Early Music in 2008. While Sant’Andrea at the time had its own maestro di cappella and some singers, it strains credibility to imagine Monteverdi not directing his own music in the church, with the assistance of other court musicians (as Bowers also believes) joining, or even replacing, those of Sant’Andrea.[15]

2. The Church of Santa Croce

2.1 Ippolito Donesmondi, the Mantuan ecclesiastical historian, explicitly stated the reason for Guglielmo Gonzaga’s decision to construct the Church of Santa Barbara, the largest palace church in Europe:

The most religious Prince Guglielmo; both because of his devotion and also for the convenience of the most Serene Eleonora, Archduchess of Austria, his consort, and for the desire that both had to attend the divine hours every day, because of the sung music (for which the small church of Santa Croce was insufficient), he initiated in this same year [1562, recte 1561] the sumptuous fabrication of the most noble temple of Santa Barbara.”[16]

Bowers himself quotes from this passage, but mistranslates picciola as “humble” and twists its meaning to declare that “only by comparison with Santa Barbara, of course, was Santa Croce in any way “humble.”[17] In neither the Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca (first edition, 1612) nor John Florio’s Queen Anna’s New World of Words, or Dictionarie of the Italian and English tongues (London, 1611) do the definitions of picciolo and umile intersect in any way. Picciolo quite simply means “small.” Donesmondi describes the church as picciola but nobile (which is the opposite of umile), in concord with the apostolic visitor Angelo Peruzzi’s 1576 description of the decorations.

2.2 Bowers bases a number of his conclusions regarding Santa Croce on Peruzzi’s 1576 apostolic visitor’s report but does not quote directly from it except for a few brief passages, mostly in reference to Santa Barbara.[18] Bowers’s comments on services in Santa Croce, based on his reading of the report, are as follows:

The Mass [Monteverdi’s Missa in illo tempore], for six voices with basso continuo for organ, was conceived on an especially expansive scale, and would have been particularly suitable for performance in S. Croce at High Mass on such occasions as the reception of foreign princes and other guests of high rank described in the Visitation Report of 1576.[19]

The manner in which service was thus conducted within the palace of Mantua for the good estate of the duke, his family, and the souls of his forebears, is disclosed by the fortunate survival of the report of an archiepiscopal visitation of the province of Bologna conducted in February 1576. This reveals that there were available two sites wherein, daily (in principle), when in residence, the members of the ducal cappella might assemble in their surplices or other ecclesiastical vestments to discharge their principal function of celebrating High Mass and observing the more important services of the Office. One such site was apparently the sizeable chapel which then occupied a central location within the Palazzo del Capitano, while the second was a larger and self-contained ecclesiastical building known as the church of Santa Croce in Corte. On most days on which the court was resident both locations were put to use.[20]

Bowers’s mention of the chapel in the Palazzo del Capitano and Santa Croce as two sites where the ducal cappella would don ecclesiastical vestments for the performance of daily Mass and Offices is confounding, since in 1576 these were performed in Santa Barbara (as observed by the visitor) by the personnel listed in Duke Guglielmo’s 1568 Constitutiones Capituli Sanctae Barbarae Manatuae, established precisely for this purpose. For an enumeration of these personnel, see main text, par. 11.2.

2.3 Letters regarding the use of the Church of Santa Croce and the visitation report itself (App. 3; main text, par. 7.8–7.13), describing the church as in disrepair and rarely used, reveal a much different picture from that painted by Bowers. Moreover, Bowers’s failure to quote the relevant passages from the report makes it impossible for readers of his articles to check the accuracy of his interpretation against the original text.

2.4 Bowers also comments on the 1592 funeral of the two-year-old third son of Duke Vincenzo, Guglielmo Domenico, in which Santa Croce played a role. The funeral, on 18 May, was described in a letter by Federico Follino (court chronicler and organizer of events) to the duke, who was away at the time. (See main text, par. 7.17–7.18, and App. 4, letter 1). Bowers describes Follino’s account rather freely:

It was within Santa Croce that Vincenzo had ordered that the body be laid in state … For the funeral itself, Santa Croce did not offer space adequate to admit and also readily to manoeuvre the immense procession of cathedral clergy and Franciscan friars, and these waited instead just inside the palace entrance. However, the principal members of the funeral procession, still numbering several dozen, duly assembled within Santa Croce, when in solemn cortège all escorted the body to Santa Barbara for burial.[21]

2.5 It is curious that Bowers would use a description of a space inadequate to admit the participants in the procession, who waited outside the palace entrance, to support an argument that Santa Croce was larger than the Sistine Chapel. But comparing Bowers’s comments with Follino’s letter (linked just above, par. 2.4), the reader can see he has also subtly misrepresented Follino’s actual description, where the number of individuals “within Santa Croce” clearly numbered far fewer than “several dozen.”

2.6 Every single written reference to Santa Croce we have been able to find directly refutes what Bowers has claimed regarding the Church of Santa Croce. It is repeatedly described as small (picciolo), and in one case “narrow” as well (conveniente alla strettezza del luogo). It clearly had devolved into limited use, especially by the duke, after the construction of Santa Barbara, and fell into disrepair to the point of requiring not only restoration of damaged fixtures, but also re-consecration of the repaired elements which were by 1576 unsuited for sacral use.

2.7 All our sources except for the two letters to and from Rome of 1575 (main text, par. 7.8–7.9) are actually cited by Bowers in his Music & Letters article, and thus available to him, but either ignored as contradicting his thesis about Santa Croce, or distorted in their interpretation or translation in order to appear supportive of it. Nowhere in our research have we been able to find a single suggestion of “grand liturgical occasions known to have been conducted within S. Croce church.”[22]

2.8 Bowers’s reaction to the studies of Santa Croce by architecture historians specializing in the ducal palace is as follows:

It must be remarked that in much recent writing a different and far smaller structure [than that claimed by Bowers] has been identified as the church of Santa Croce [citations].… This proposal must be considered unsustainable, since it appears indisputable that the diminutive two-bay structure so identified was far too small ever to have been the locale for the elaborate ceremonies described in the visitation report of 1576 and the funeral report of 1592 … moreover, the building so identified was located actually some distance to the south of the position indicated for Santa Croce by [Gabriele] Bertazzolo on his engraving of 1628.[23] Rather, this tiny structure was ideal in size, character, and location to be identifiable as the separate ducal oratorium secretum described in 1576.[24]

2.9 We have already shown that neither the 1576 visitation report nor Follino’s letter of 1592 describing the funeral of Guglielmo Domenico support in any way Bowers’s contention that elaborate ceremonies were conducted in Santa Croce. Nor do any of the other descriptions of the church and its functions. But how is it that someone who neither shows nor claims any expertise in architectural history and forensics can dismiss out of hand the work of those who not only have expertise in the field, but have employed it specifically in the careful and detailed study of the corte vecchia and the Church of Santa Croce, without even attempting to counter the analysis and arguments in those studies? How can he claim credibility for his own thesis, which is contrary to every aspect of those studies, without engaging them?

2.10 Here is what Bowers has to say about the corte vecchia in the two maps engraved by Gabriele Bertazzolo, published in 1596 and 1628 respectively:

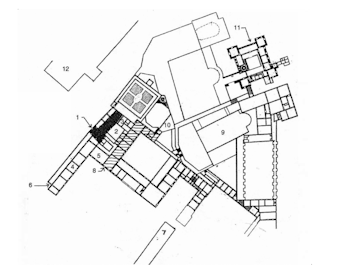

Bertazzolo’s engravings show that the church stood within the Corte Vecchia, and lay along the northern flank of the internal Cortile di Santa Croce. It is clearly depicted as having occupied the greater part of the oldest of the palace’s many component buildings, that known as the Magna Domus. As still somewhat crudely pictured in 1628, it was laid out on a liturgical east-west alignment parallel to that of the cathedral just across the piazza. Its design is presented as having extended to an unaisled nave of some three or four bays, one supporting the tower and spire. A putative but obligatory additional bay, forming an eastern chancel and sanctuary, is unfortunately obscured by the perspective of the plan.[25]

But the plan is quite different from Bowers’s description, and we are unable to find any basis for his claims. For extensive discussion of the Bertazzolo engravings, see main text, par. 8.1–8.10.

2.11 We also find ourselves confused by Bowers’s comments on the tower and spire of the church. Citing Bertazzolo’s 1628 engraving, he declares of the Magna Domus that “its design is presented as having extended to an unaisled nave of some three or four bays, one supporting the tower and spire.” In the footnote to this sentence, we read the following: “The location of its remains shows that in fact the tower was not central, but western [northern in our terms]”; here he cites Stefano L’Occaso’s studies of the medieval structure of the Magna Domus.[26] L’Occaso’s discussion is about a tower over the entrance to the palace, which was at the southern end of the Magna Domus and joined with the Magna Domus in 1308. But Bowers cites this tower and the Magna Domus as “the space which in c. 1420–5 was to be converted into Santa Croce church.” Yet the spire of the church in both Bertazzolo engravings, which Bowers employs to prove his thesis, is unequivocally at the northern end of the cortile di Santa Croce, not the southern end, and cannot be the tower described by L’Occaso. We fail to comprehend how to reconcile these contradictory observations.[27]

2.12 The prior existence of the Magna Domus leads Bowers to claim that Santa Croce was not constructed in the period 1420–25, but rather converted from the Magna Domus: “This conversion was finally accomplished c. 1420–5.” He goes on to declare that “Bertazzolo’s plan shows clearly that hereby there was preserved intact the narrow northern flank of the Magna domus facing the Piazza di San Pietro, while the church was created by means of the conversion to sacred use of all five bays of the structure’s broad southern flank.”[28] Bowers supports his assertion by means of an unattributed architectural drawing, apparently his own (our Fig. A.1), in which his putative open-nave Church of Santa Croce is blackened, thereby obscuring the actual room divisions of both the ground floor and piano superiore clearly marked in Bernardino Facciotto’s 1580–81 plan of the ducal palace and Gaetano Crevola’s 1773 plans of the corte vecchia (Figs. 16, 20, 21, discussed in main text, par. 8.12–8.13).[29] He repeats the argument later, illustrating his point with a detail from Crevola’s ground floor plan (Bowers, plate 6), declaring that “it appears that the lines of the ancient walls within which the church was contained can be clearly perceived on a ground-floor plan of the Magna Domus made in 1773” (i.e., our Fig. 20).[30] But despite Bowers’s darkening of the same space on Crevola’s plan as in his own diagram (Fig. A.1), the separate rooms on Crevola’s plan remain clearly visible, negating, as before, his claim that this space had been an open nave. Again, we are unable to find any justification for Bowers’s description or his conclusion.

Bowers’s key:

- Church of Santa Croce (shaded)

- Cortile di Santa Croce

- Ducal “Oratorium secretum” of Holy Cross

- Sala della Crocefissione

- Sala del Pisanello

- Palazzo del Capitano (whole range)

- Collegiate Canonica of Santa Barbara

- “Appartamento Verde” of Duke Guglielmo (hatched)

- Basilica di Santa Barbara

- Sala dello Specchio

- Castello di San Giorgio

- Cathedral Church of San Pietro

2.13 Bowers identifies his no. 3 as the “ ‘oratorium secretum’ of Holy Cross,” i.e., the “oratorium secretum” mentioned in the 1576 visitation report of Angelo Peruzzi (see App. 3, par. 1.8, and main text, par. 9.1). Bowers is both correct and mistaken in identifying this space, numbered 34 on the 1773 Crevola ground plan (Fig. 20) and no. 81 on the Crevola piano superiore plan (Fig. 21), as the “oratorium secretum.” What Bowers has failed to recognize is that this space comprised two distinct levels: the “oratorium secretum” occupied not the ground floor but the second level of the structure, and the consecrated Church of Santa Croce lay directly beneath it, at ground level.[31] The duke’s oratorium secretum, on the upper level—whose wooden altar and images of saints the visitation report of 1576 describes—was accessible separately from the level of Duke Guglielmo’s apartments.

2.14 Bowers justifies his separation of the oratorio of Santa Croce from the church by misinterpreting the opening phrase (“Apud eandem ecclesiam visitavi oratorium secretum serenissimi ducis”) in par. 8 of Peruzzi’s visitation report (App. 3, par. 1.8). He declares, “Use of the preposition apud (in the close vicinity of) rather than intra (within) or iuxta (adjacent to or contiguous with) served to indicate that the oratory lay separate from the church of Santa Croce, but still in its immediate vicinity.”[32] He must interpret apud as meaning “in the close vicinity of” in order to sustain his claim about the location and large size of the Church of Santa Croce as a separate structure elsewhere. Thus, he has declared as fact, without providing any rationale, one possible interpretation of the word apud and ignored another: “at,” consistently used in this period to identify publishers on the title pages of prints (e.g. Venetijs, apud Ricciardum Amadinum, as in Monteverdi’s 1610 publication). We argue that Peruzzi’s apud must be understood as “at” in the sense of “at this same church I visited a separate [or private] oratory of the most serene duke.”

2.15 Ironically, Bowers has used his interpretation of apud to locate this oratory where it actually was:

It is in fact still possible to identify exactly the location of this oratory, since there can be little doubt but that it is marked by the presence of certain fragments of ecclesiastical architecture of late Gothic date found embedded within the successor suite of rooms located on the eastern side of the Cortile di Santa Croce. This mere oratory was, however, far too tiny ever to have been used for any liturgical purpose involving ceremonial music.[33]

That said, both the frequent references to the oratorio as sopra Santa Croce (main text, par. 8.13 and main text, par. 9.3–9.4), and the architectural remains, as analyzed by Rodella and L’Occaso, indicate that the Church of Santa Croce from its inception had been divided into two levels (remodeled into three in the late eighteenth century).[34] Thus, Bowers’s comment on the oratorio as “far too tiny … for any liturgical purpose involving ceremonial music,” applies also to the Church of Santa Croce below, confirming Donesmondi’s report: it was a desire for elaborate sacred music—for which Santa Croce was too small—that led Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga to build the “noble temple” of Santa Barbara.

2.16 As we have shown, neither Facciotto’s piano superiore plan nor Crevola’s pian terreno and piano superiore plans support Bowers’s thesis. Bowers himself notes the similarity of the plans, but then declares that “The former [Facciotto’s] plan thus appears in fact to have originated at a date in the 17th c. or even later; so that its depiction of a domestic pattern of rooms at the Magna Domus location in which Bertazzolo shows Santa Croce to have been standing in 1596 and 1628 [emphasis ours] is of no consequence to the present discussion.”[35] Thus, since Facciotto’s plan contradicts Bowers’s thesis, it must not date from the period of his construction in the corte vecchia, amidst all his other plans relating to that construction, or even from Facciotto’s lifetime, and it must be discarded as irrelevant (though Bowers offers no evidence for such a bizarre declaration).

2.17 Bowers also asserts:

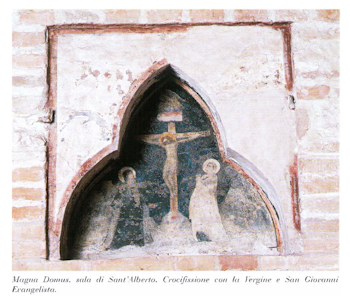

Of the erstwhile church the last surviving trace is a small trilobe niche of late medieval date, its interior decorated with a painting of the Crucifixion with Saints Mary and John … [which] appears to have been a small closed aumbry, certainly for sacred use (and perhaps for the reservation of the Sacrament), incorporated into a western gallery occupying at this point the building’s whole width (see Fig. A.2).[36]

2.18 This niche in the Sala di Sant’Alberto (Sala dei Fiamminghi) in what was originally the tower incorporated into the Magna Domus in 1308 may be thought the remnant of a small chapel (cappella parva) of Saint Francis cited in a document of 1393. On the other hand, the brief description of the chapel of Saint Francis, mentioning an adjacent studiolo, suggests a different, unknown location.[37] In any event, particularly problematic for Bowers’s argument is that the Sala di Sant’Alberto is situated on the piano nobile, whereas Bowers locates his Church of Santa Croce on the ground floor. Bowers’s declaration that such a niche signifies a pre-existing church in that space, larger than the Sistine Chapel, contradicts his own thesis of the church’s location on the ground floor.

3. The Church of Santa Barbara

3.1 Bowers’s position on Wert’s role at Santa Barbara is as follows:

Wert had never occupied any formal office at Santa Barbara at any time. He was never its maestro di cappella, for the simple reason that no such office existed there until 1588, when it was established not for him but for Gastoldi. However, it is clear that from his position of eminence as maestro di cappella of the ducal household, Wert had for the lengthy period prior to Gastoldi’s appointment exercised—albeit from a distance—a strong determining influence over music making at the basilica, advising duke Guglielmo and composing much polyphony for the musicians of its internal chorus.[38]

The documentary record, however, refutes this. (See main text, par. 11.6.)

3.2 Bowers describes Santa Barbara—which, as we have seen, eventually met its normal expenses with its own income—as “wholly independent of the ducal household,” and he refers to the “totally separate church, choir, and musicians of Santa Barbara.”[39] Yet, only two pages later, after reiterating Tagmann’s finding that “until about 1582 Santa Barbara employed no full-time professional singers on its own account,” Bowers goes on to say:

Indeed, it had no need to do so, for when suitable Guglielmo was prepared to supply the services of the singers of his own cappella. Thus in 1578 and again in 1579 correspondents noted on his behalf the manner in which he was prepared to make the maestro, organist, and singers of his cappella available for the basilica, seeking from the Abbot and Chapter no payment in return for this generosity.

Presently, however, such arrangements necessarily ceased. During 1581–83 Guglielmo received final papal authority for the implementation and observance within the basilica of its own unique liturgy, compiled during the preceding years at his initiative and under his personal direction—and upon the full inauguration of the Santa Barbara liturgy it ceased to be practicable for the basilica to borrow singers from Guglielmo’s household any longer. The Santa Barbara liturgy was authorized for use solely within the basilica and nowhere else. Thus the duke enjoyed no capacity to direct its adoption also at services held in Santa Croce and the Corte Vecchia chapel by the staff of his own household cappella, who consequently must perforce have continued to observe only the standard Tridentine liturgy universally authorized. It was impractical to expect Guglielmo’s singers to have to stumble between one liturgy on their home ground and another, pervasively and significantly different, in Santa Barbara. With effect from 1582/83, therefore, the chapter of Santa Barbara ceased to borrow the ducal cappella, and began to appoint professional singers of its own.[40]

3.3 There are a number of problems with these assessments, which are manifestly false. In the first place, an earlier form of the Santa Barbara liturgy had provisionally received papal approval in 1571, as noted above, and had already been continuously sung, with ongoing revisions, from 1567.[41] There was therefore no abrupt change in the liturgy with the publication of the breviary of 1583 and the final completion of the chant revisions in 1584. Secondly, the Santa Barbara missal was used in Santa Croce for services when the duke was present (see main text, par. 7.11, and App. 3, par. 1.5). Thirdly, the liturgy of Santa Barbara was sung mostly in plainchant, falsobordone, or simple polyphony. As Bowers himself puts it:

In musical terms, the concern and emphasis of the statutes lay entirely on the achievement of perfection in the rendering of the plainsong of the services. There was nothing to stop the priests, clerks, and boys embarking upon the performance of polyphonic music, whenever suitable.… it appears that in respect of music-making actually by members of the foundation, the founder and the chapter envisaged nothing more elaborate than items in unwritten polyphony improvised to plainsong (e.g. falsobordone), or sung in such relatively undemanding styles of written polyphony as those composed to Guglielmo’s special commission by Wert and Palestrina.[42]

3.4 Bowers’s concern over singers stumbling between one liturgy and another is misguided. The singers from Vincenzo’s cappella supplementing those in Santa Barbara would not have been performing the Santa Barbara plainchant, which differed from the Roman rite, but rather polyphonic psalms, canticles, hymns, masses, responsories, lessons, and other liturgical items whose texts are identical or only slightly different from the Roman rite, even if some of them were distributed differently between the two liturgies. Contrasts between the two rites would have been a matter of indifference to the singers from the ducal cappella performing polyphony in Santa Barbara to the same texts with which they were familiar from the Roman rite. If any of the unique texts on the two annual feasts of Santa Barbara had been performed in polyphony requiring (as likely) more professional singers than those on the Santa Barbara payroll, rather than in plainchant, falsobordone, or few-voiced polyphony, it would hardly have been overly cumbersome for the ducal singers to learn them.

3.5 Apart from his inaccurate declaration that Santa Barbara was “wholly independent of the ducal household,” Bowers makes another “statement of fact” regarding Monteverdi and the Church of Santa Barbara: “It has already been established that Monteverdi was never associated with the music of Santa Barbara. He never occurs on its chapter’s surviving payrolls as either a member of the collegiate foundation or as an employee, and not a note of his music was contained within its library of polyphony for performance at service.” He cites as his authority Iain Fenlon’s article “The Monteverdi Vespers: Suggested Answers to Some Fundamental Questions.”[43] But Bowers has misrepresented his source. What Fenlon said, in an article that was already long outdated by 2009 and had been superseded by other studies well before the publication of Bowers’s article:

A strong argument against the idea that the Vespers were written for Santa Barbara is that the cantus firmus of Monteverdi’s Ave maris stella is from the Roman rather than the Santa Barbara use.… All these arrangements argue against uncanonical services such as the Vespers being held there, and not only did Monteverdi never have responsibility in the chapel, the Santa Barbara library of music which survives virtually complete contains none of his music.[44]

3.6 But in 1998, in an essay Bowers cites in his Music & Letters article, Paola Besutti, through more detailed study, demonstrated just the opposite of Fenlon’s conclusion: the Ave maris stella cantus firmus and its text underlay, as well as a slightly divergent Ave maris stella by Giaches de Wert from the church’s library, are closer to the Santa Barbara rite than to the Roman rite.[45] As Besutti states in her concluding summary: “As none of these (by no means minor) features [of Monteverdi’s Ave maris stella] occur in the many examined contemporary Gregorian sources of Roman or north-Italian provenance, there is sufficient cause to conclude that the cantus prius factus of Monteverdi’s hymn was drawn not from any Roman hymnal, but specifically from the book in use at the Gonzaga chapel of S. Barbara.” Once again Bowers misrepresents the purport of his source, declaring, in justifying his theory, that the hymn had undergone recomposition for “a putative adaptation for chamber use”: “It [the Ave maris stella cantus firmus] diverges also from the Santa Barbara version of the chant.”[46]

3.7 But apart from Bowers’s misrepresentation of Fenlon’s argument as a blanket claim that Monteverdi “was never associated with the music of Santa Barbara,” and ignoring Besutti’s contradiction of it, the idea that the absence of any of Monteverdi’s music in the Santa Barbara library proves that Monteverdi never had anything to do with music there does not meet the test of basic logic. It is impossible to prove a negative of this sort: the absence of evidence is not the evidence of absence. Nor does the absence of evidence mean “It has been established.” The absence of Monteverdi’s music from the Santa Barbara library by no means proves that he didn’t compose for the church. Paola Besutti has more recently introduced evidence that the library of Santa Barbara as preserved in the Conservatory of Milan is, in fact, missing part of its original contents (see main text, par. 11.25).

4. Monteverdi as Church Musician in the Gonzaga Court, 1590–1612

4.1 At the outset of his Music & Letters essay, Bowers asserts that “it has long been considered that his engagement there was as almost exclusively a secular musician involved but little with sacred music. However, a new appraisal of the evidence suggests that this may be rather a misapprehension.” A footnote to this statement says, “For an initial assessment of this evidence, see Roger Bowers, “Monteverdi at Mantua” in The Cambridge Companion to Monteverdi.[47] Bowers’s claim to be the first to acknowledge Monteverdi’s significant role as a composer and performer of sacred music ignores the statement by Giulio Cesare Monteverdi in the Dichiarazione in Claudio’s Scherzi musicali of 1607 about Monteverdi’s responsibilities for both the church and the chamber (see par. 4.6–4.7 below) as well as the long history of quotations, citations, and discussions of just this evidence in the secondary literature on Monteverdi. Guglielmo Barblan, Domenico Paoli, Denis Stevens, and Paolo Fabbri, none of whom is cited by Bowers, had all written previously of the evidence, limited as it is, of Monteverdi as a composer and director of sacred music in Mantua, apart from the Mass and Vespers of 1610.[48] Bowers’s article in the Cambridge Companion to Monteverdi focuses at first on his theory regarding the Church of Santa Croce and then incorporates most of the well-known information about Monteverdi’s activity in sacred music at Mantua into his account of Monteverdi’s years there. To call this an “initial assessment” is, as already suggested, inaccurate. In fact, in the very same volume, Kurtzman had published the article requested of him by the volume’s editors, “The Mantuan Sacred Music” (a draft of which was sent to Bowers at least a year before the volume’s publication), which is actually the first synthesis known to us (though certainly not advertised as such) of what had appeared about Monteverdi’s sacred music in scattered form in these earlier publications, plus Kurtzman’s own commentary on the Mass and Vespers of 1610, about which he has been publishing since 1972.[49]

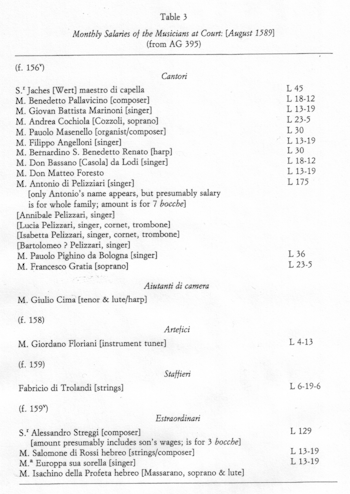

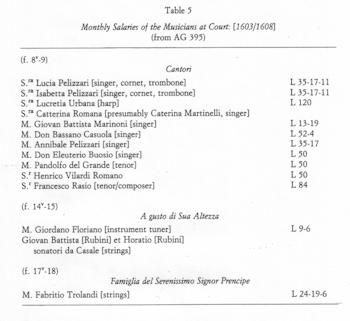

4.2 We turn now to the performing resources for sacred music in the Gonzaga household. In assessing the size and personnel of the duke’s cappella, Bowers refers to two payroll documents from the Archivio Gonzaga (AG) in the Mantuan state archive: b. 395, fol. 156v, and b. 3146, fol. 64r. These payroll lists were first published and discussed by Susan Parisi in her PhD dissertation, and subsequently with much expanded commentary in her article “Musicians at the Court of Mantua.”[50] Bowers cites from the list in AG b. 395 “a principal chaplain, four priests, a maestro di capella and ten singers” (see Fig. A.3).”[51] But neither these numbers nor all these positions are derivable from this list.

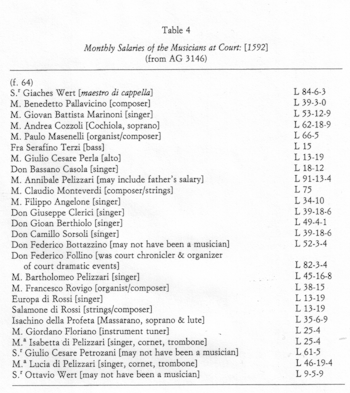

4.3 The document AG b. 3146 (see Fig. A.4) is dated by Bowers as “some month apparently towards the end of the year 1591,” though Parisi dates it as 1592 based on the absence of Alessandro Striggio, who died on 29 February 1592, and the presence of the organist and composer Paulo Masenelli, who left Mantua in December 1592.[52] Bowers breaks this list down into “a principal chaplain, four other chaplains (several likely to be qualified additionally as singers), a maestro di cappella, and ten adult male singers,” under which he includes the composers Benedetto Pallavicino and Monteverdi, as well as the organist Paulo Masenelli, but skips Annibale Pelizzari.[53] If we assume that both Pallavicino and Masenelli also sang, the number ten doesn’t include the three or four singing priests. The remainder of the list, which Bowers says “Vincenzo employed primarily for the salon, by 1591 numbered some eleven.” However, the remainder of this list numbers ten, not eleven, and includes the organist of Santa Barbara, Francesco Rovigo (who also served at court), the instrument tuner Giordano Floriano, and two others, Giulio Cesare Petrozani and Ottavio Wert, for whom Parisi was unable to find evidence of their being musicians. Bowers acknowledges:

Doubtless the boundary between the two groups was at this time very porous; it seems likely that the members of the cappella were routinely available also for secular music-making in the salon, while the male Christian members of the salon group could doubtless be made available for service in church and chapel when appropriate on special occasions.[54]

4.4 But what and where are the “church and chapel” that Bowers mentions? According to Bowers, the Church of Santa Barbara “was wholly independent of the ducal household.”[55] For Bowers, that leaves only the Church of Santa Croce, which, as already noted, he must displace to a new location where he claims it was “slightly larger than the Sistine Chapel” (main text, par. 1.3). But, as we have demonstrated in the main text, chapters 7–9, it was located where the architectural plans show it to have been, was small, rarely used, and serviced, when needed, most often by a pair of mendicant friars from various local orders. On the occasion of sung masses, sometimes ten or twelve friars from one or another of the orders might come to perform the celebration (main text, par. 7.11).

4.5 The largest other chapel in the palace was in the Palazzo del Capitano, which may even have been used occasionally for public events (main text, par. 10.6). There were also three small chapels in the Castello San Giorgio (main text, par. 12.7). In the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century, Vincenzo had a chapel constructed in his own apartments in the corte vecchia, but it is not clear it was available as early as 1592 (main text, par. 12.6).

4.6 That Monteverdi was active as a composer of sacred music for Vincenzo is proven not only by his newly acquired appointment, likely in early 1592 (see main text, par. 4.31), but, as already mentioned, by Giulio Cesare Monteverdi’s Dichiarazione della lettera stampata nel quinto libro de’ suoi madrigali (1605), published in the Scherzi musicali of 1607. In this famous response to Giovanni Maria Artusi’s L’Artusi, ovvero, delle imperfezioni della moderna musica of 1600, Giulio Cesare notes that he is responding in place of his brother, who is too busy “non solo per il carico de la musica tanto da chiesa quanto da camera che tiene, mà per altri servitij non ordinarij … hora in tornei, hora in balletti, hora in comedie, e in varij concerti …” (not only because of his responsibility as much for music for the church as for the chamber, but also because of other extraordinary services … now with tourneys, now with ballets, now with comedies and various concerts …). Monteverdi also reports, in a letter of 26 March 1611 to Prince Francesco Gonzaga at Casale Monferrato, that he is sending him a Dixit [Dominus] for eight voices, a two-voice motet for the Elevation, and a five-voice motet for the Virgin. He then promises to send some madrigals “once Holy Week is over,” since at the time of writing he must have been fully occupied both composing and leading the ducal cappella, not only in 1611, but annually.[56]

4.7 Giulio Cesare’s wording suggests that Claudio’s regular duties (in contrast to the “extraordinary” ones) were approximately equally divided between church and chamber music. Could services in the small court chapels have demanded so much of his compositional and directorial time? These would have infrequently involved anything more than chant. Apart from the possibility that he may have composed sacred music for Santa Barbara (see par. 3.5–3.7 above; main text, par. 11.25–11.26)—a possibility that remains undocumented—Sant’Andrea and Santissima Trinità are prime candidates as well as San Pietro for such activity (main text, chapters 3–5). Occasional visits to other churches in Mantua may also have entailed music composed and directed by Claudio (see main text, chapter 6). Moreover, Vincenzo may have taken Claudio and other members of the cappella with him on his many sojourns to his villas and other locations in the vicinity of Mantua, or even more distant travels for which we have no information. But wherever it may have been, it is clear that Monteverdi was significantly occupied with the composition and direction of sacred music from 1592 until his employment was terminated in the summer of 1612 and that a substantial part of his activity must have been outside the palace itself.

4.8 According to Bowers, another salary list, which is contained in AG b. 395, fols 3–23, dates “to some month lying between January and November 1605” and

indicates that the corps of star singers and instrumentalists of the salon, then numbering twelve (four of them female), had come to be regarded as an elite body of musicians suitable for retention on the Treasury payroll, while all the others [i.e., other musicians] were relegated to some inferior means of payment. Monteverdi and the rank-and-file cantori of the cappella were excluded from the elite group, and appear nowhere on this list.[57]

4.9 This document (see Fig. A.5), cited by Parisi as well as Bowers, lists 11 singers and instrumentalists (some of the singers played instruments as well) on fols. 8v–9, headed by the label cantori; a tuner and two string players on fols. 14v–15, labeled A gusto di Sua Altezza (at the pleasure of His Highness). The salaried total is twelve, supplemented by the two supernumerary strings hired according to the duke’s volition.[58] Parisi’s analysis of the possible dating of these lists, based on the presence and absence of individuals whose arrival and departure from the court are known, places them between 1603 and 1608. Where Bowers obtains his more precise dating “to some month lying between January and November 1605” remains without explanation. His designation of this group as singers for the “salon” also remains unexplained. There is no expressed rationale for his excluding either the male singers or the female singers and instrumentalists from performing in Santa Barbara, or the male singers and instrumentalists from participating in any other sacred venue where members of the cappella performed. Indeed, the instrumentalists would have had to do so, since none of the institutions we have described had instrumentalists (other than organists) on their payrolls. The female singers and wind players, Lucia Pelizzari and Isabetta Pelizzari, are documented as having sung in Santa Barbara; Lucretia Urbana and Catterina Romana may well have sung or played instruments in Santa Barbara as well.[59] While there is a distinction between “salon” (i.e. secular venues) and ecclesiastical venues, there is no reason to assume a distinction between singers and instrumentalists for one or the other. The duke’s cappella, including females where they were allowed, sang and played in both as needed.

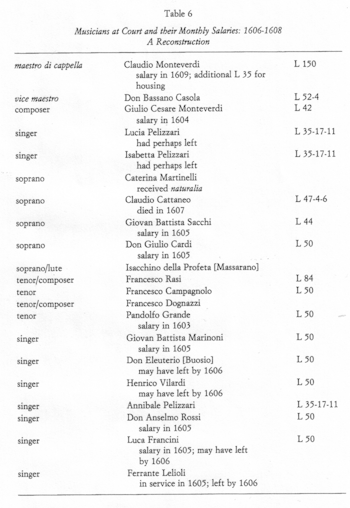

4.10 Why Bowers designates these performers as an “elite” group also receives no explanation, nor is there any explanation offered as to why the maestro di cappella, Claudio Monteverdi, and other musicians, such as the famous tenors Francesco Rasi, Francesco Campagnolo, and Francesco Dognazzi, should have been relegated to an “inferior” means of payment.[60] It is obvious from Parisi’s analysis of surviving pay registers that they are spotty and incomplete. From other documents, Parisi was able to reconstruct a roster of court musicians and their monthly salaries for the period 1606–8 (see Fig. A.6).[61] This roster contains eighteen singers, including two who had left by 1606 (but excluding Claudio Monteverdi), nine string players (also excluding Monteverdi), and a variety of other players of keyboard instruments, harps, and winds. It is also possible that Giulio Cesare Monteverdi, who was an organist (see main text, par. 3.27), may have also been a singer, like his brother. This roster does not suggest that the number of singers was fixed at ten.

5. Monteverdi’s Composition of Sacred Music, 1590–1612, as Represented by the Mass and Vespers of 1610

5.1 Attempting to explain why the only surviving sacred music by Monteverdi from his Mantua period are those pieces published in the Mass and Vespers of 1610, Bowers declares:

Through the availability to him of singers and instrumentalists of outstanding capacities, he was able to compose music whose performance few other institutions in Italy or anywhere else could realistically contemplate. Commercially, its [Monteverdi’s Mass and Vespers] publication was therefore not a viable proposition; there was simply no sufficient number of potential buyers. Consequently, it may be understood to have been not even partially for satisfaction of the market that he planned his album of sacred music of 1610. It was never intended to be merely an ordinary working volume for the use of any conventional ecclesiastical choir; rather, its role was to be primarily a representative showcase of its composer’s talents, offered essentially for admiration.[62]

5.2 We agree that Monteverdi’s print (as a whole) “was never intended to be merely an ordinary working volume for the use of any conventional ecclesiastical choir” and that one of its roles (but not to the exclusion of others) was to represent the composer’s talents, but not that it “was offered essentially for admiration.” Bowers’s claim that Monteverdi’s sacred music would not have had enough potential buyers is belied by the state of sacred music publication in Italy in the last decade of the sixteenth century and the first decade of the seventeenth century.[63] (See main text, chapter 13.)

5.3 Bowers makes several statements about specific pieces from Monteverdi’s Mass and Vespers that do not survive examination. Regarding the Missa in illo tempore, he opines:

Probably a mass founded upon music set originally to a text [from Luke 11:27–28] so broadly acceptable at service was considered perfectly suitable for performance on any prominent occasion—not least, perhaps, at High Mass in Santa Croce in the presence of foreign princes and other guests of high rank, as described in the Visitation Report of 1576.[64]

5.4 We have already demonstrated the inaccuracy of Bowers’s commentary on the apostolic visitation report of 1576 (main text, par. 7.11–7.12; par. 2.2–2.3 above). Whether the Missa in illo tempore was ever performed in Mantua is unknown, though performance corrections and annotations in various surviving copies indicate that it was performed elsewhere. It was copied in Rome into Sistina Cappella MS 107 without the organ part, since no instruments were used in the Sistine Chapel.[65] The manuscript was restored on two occasions, testifying to actual performance in the chapel. Performance elsewhere is also suggested by its 1612 publication in Antwerp by Pierre Phalèse in an anthology curated by Orazio Vecchi, again without the organ part.[66]

5.5 Bowers notes with regard to a letter of 26 July 1610, by Bassano Cassola to Cardinal Ferdinando Gonzaga, describing the mass as requiring “much study and effort,” that “nothing in this passage suggests that Monteverdi’s ‘much study and effort’ were necessarily immediately recent.” But the purpose of the letter was to report fresh news about the mass and vesper psalms that Monteverdi was coming to Rome to dedicate to the pope, as well as other compositions that were eventually published in the Sixth Book of Madrigals in 1614. In that context, it seems likely that Monteverdi was in the process of completing, or had only recently completed, the mass, otherwise the detailed description for Ferdinando would have been unnecessary.[67]

5.6 We have no objection to Bowers’s descriptions of the psalms and Magnificats of Monteverdi’s Vespers, which are in accord with those previously published by John Whenham and Kurtzman, other than a footnote regarding the high clefs of the Magnificats, which denies the relevance of these clefs for pitch level in performance. This is a position with which we strongly disagree, though this is not the place to enter into an extended discussion of the issue, which has already been much vetted in the musicological literature.[68]

5.7 In speculating on occasions for the composition and first performance of the Magnificat for seven voices and six instruments, Bowers suggests “the state visit to Mantua made by Pope Paul V in 1607,” without citing any source of information about this visit. In fact, there is only one such original source: Kurtzman’s book The Monteverdi Vespers of 1610: Music, Context, Performance. Unfortunately, Kurtzman misinterpreted at the time the relevant passage in Donesmondi, which he quoted in a footnote.[69] Donesmondi’s remarks speak only of the pope favoring Sant’Andrea with indulgences at the beginning of 1607, not of an actual visit to Mantua. A copy of the diary of the Sistine Chapel’s Master of Ceremonies, Paolo Alaleona, shows that Pope Paul V remained in Rome throughout the first half of 1607, with the exception of a few brief summer excursions to cardinals’ palaces near Rome, making no such “state visit” to Mantua.[70] By offering his claim without citation, Bowers again presents his readers with an unsubstantiated “statement of fact” that turns out not to be a fact at all, which an attentive reader of Kurtzman’s footnote, with the Donesmondi wording, could have ascertained.

5.8 While Bowers’s discussion of the individual psalms and Magnificats is, with the above exceptions, satisfactory, that of Monteverdi’s sacri concentus is problematic in its limitations and underlying assumptions. Foremost among these is that texts not officially sanctioned by the liturgy would not have been performed as part of a liturgical service. According to Bowers:

Monteverdi’s duties for his employer evidently extended also to the composition of miscellaneous motets characterized by instrumental accompaniment either continuo or obbligato, set to texts which were of a sacred nature but owned no place in any authorized liturgy. That is, such pieces were intended less for use in church or chapel, intruded without authority into the course of Mass or Office, than as edifying chamber music of a sacred nature, performed in the salon for upliftment as well as for entertainment on occasions when the lord of the house felt minded to call for moments of reflection and devotion.[71]

5.9 While Bowers seems to leave the door open a crack to the possibility of non-liturgical texts intruding “without authority” into the Mass or Office, his commentary on Monteverdi’s sacri concentus is exclusively within the framework of devotional performance of what he calls “non-liturgical” texts at court outside of any liturgy. That usage, of course, is one possibility, with which we have no argument, but Bowers ignores the other equally real possibility: that such motets might be inserted into the performance of the liturgy as an integral part of that performance. He also insists, incorrectly, that the hymn Ave maris stella lies outside the liturgy, including it among the non-liturgical “motets.”[72]

5.10 Bowers’s view on the Vespers part of Monteverdi’s 1610 print unfolds as follows:

There has been much debate concerning the character of the Vespers section of this publication, and its identity as either (1) a unified aesthetic whole, offering a serial menu for the presentation of a self-contained, unitary, and comprehensive service of festal Marian Vespers, or as (2) no more than a superficially tidy aggregation of piecemeal and discrete single items, assembled and ordered simply for the purpose of publication. Of these, the first interpretation has long been in the ascendant. Nevertheless, it has persistently given rise to contradictions, inconsistencies, and irrationalities that have defied all satisfactory resolution, and the material offered here, aligned with some other recent research, does suggest that it is now possible to propose that it appears anachronistic and unsupported. Rather, many features of this volume—and, not least, the composer’s own words—strongly favour the alternative interpretation, that it is but an ordered aggregation of discrete items.

In particular, in every respect these pieces were in nature extremely diverse, and in his own words Monteverdi offered his selection not as any sort of unity, but as simply and solely a miscellany.… In his own estimation … his volume contained only a tidy compilation of individual pieces, whose engagement of a loosely methodical ordering he was presenting as conveying no suggestion at all of the presence of any internal pattern of coherence, either ecclesiastical or aesthetic.[73]

“In his own estimation” refers to the opening sentence in Monteverdi’s dedication to Pope Paul V: “Res quasdam Ecclesiasticas modulis Musicis concinendas quum in lucem emitter vellem, Maiestati tuae (Pontifex Pontificum) qua verè nulla ad Deum propius accedit in orbe mortalium, nuncupare decreveram …” (I wished to bring to light [publish] certain ecclesiastical things to be sung in music, for your Serenity, Pope of popes, whom I believe is closer to God than any earthly mortal). This is such a nonspecific and formulaic way of speaking that to claim that Monteverdi considered “his volume … only a tidy compilation of individual pieces … as conveying no suggestion at all of the presence of any internal pattern of coherence” is to impose on Monteverdi’s verbiage a meaning it simply does not justify. From this interpretation Bowers goes directly on to say,

From the invaluable and exhaustive researches of Jeffrey Kurtzman it is possible to conclude that up to 1610 composers had as yet engendered no regular practice whatever of issuing music to be either perceived or received as constituting a specific and self-contained menu for the performance of a single service of any class of festal Vespers.[74]

Such a statement might be flattering if Bowers’s conclusion were not exactly the opposite from what those exhaustive researches actually demonstrate (main text, par. 14.2–17.5).

5.11 Bowers attempts to support his conclusion by reference to Monteverdi’s Bassus Generalis title page, which he translates as saying “For the Most Holy Virgin, a Mass for sixfold voices [suited] to the choirs of churches, and Vespers to be sung by more [voices], with certain sacred concerti, works suited to the chapels of the chambers of princes.”[75] Apart from misinterpreting “pluribus” as “more,” instead of its clear meaning here as “several” [voices] or “a number of” [voices] (thereby removing the inconsistency Bowers claims between the six-voice mass and other six-voice pieces in the print), Bowers insists that the six-part scoring, “certainly further identified the performance of the sacri concentus written for fewer than six voices as possessing no envisaged propriety with any Vespers service.”[76] Other scholars, too, have noted the three-fold distinction of compositions on the title page—Missa, Vesperae, sacri concentus—and taken that to prove that the sacri concentus have no role in a Vespers service, though Bowers has taken matters even further by claiming that the sequence of psalms constitutes “discrete and non-sequential pieces” upon which Monteverdi has imposed “a cogent but purely cosmetic means of ordered presentation.”[77] This last phrase is especially befuddling, raising questions about what is meant by “cogent” and “cosmetic.” For our discussion of the title page, see main text, par. 14.3–14.5.

Sonata sopra Sancta Maria

5.12 Bowers attempts to make a case for a strictly proportional structure underlying the Sonata sopra Sancta Maria:

Not the least of the many remarkable characteristics of this piece is the pattern of mathematical equivalences and ratios by which its structure is underpinned. These constitute a rational pre-ordering of its prevailing ingredients of contrast and diversity, apparently undertaken to procure structure and cogency and to pre-empt any risk of descent into unstructured rambling. These patterns all grow from inventive manipulations of the first four primes after 1, namely the numbers 2, 3, 5 and 7. Thus the formula 2 x 3 x 72 yields the number 294, which in terms of semibreves produces the total length of this movement. Within this duration, the formula 7(5:25:5) generates the proportion 35:224:35, which, in semibreves determines the constituent lengths of the movement’s ternary structure A:B:A. Moreover, the alternating passages of tactus equalis and tactus inequalis (duple and triple time respectively) exhibit in aggregate the ratio 1:1, arising from the manner in which the formula 72 x 3, generating the number 147, determines the total number of semibreves under each mensural disposition. Probably it is no accident whatever that the next prime, 11, yields the number of utterances of the text.[78]

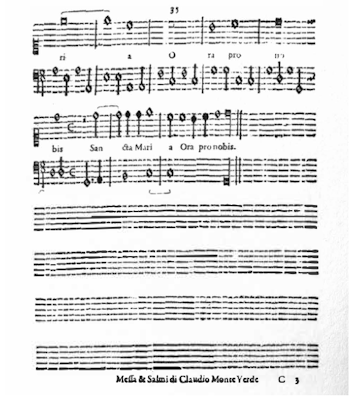

5.13 Bowers had already presented this idea in a slightly different form in 1992, to which Kurtzman voiced his objections at the time.[79] Rather than repeat any of the arguments presented there, we will focus on the fundamental observation that Bowers’s numbers are simply inaccurate. Bowers bases his total number of semibreves on the Bassus Generalis partbook, declaring that the final “breve” (recte longa) is ultra mensuram and not to be counted.[80] On that basis, Bowers counts the total number of semibreves as 294. But that is not the way Monteverdi understood it, for in the Cantus partbook, Monteverdi prints the vocal part and the Bassus Generalis together in score, where one can see that the cantus actually continues in mensural notation well into the Bassus Generalis’s final longa (see Fig. A.7).

5.14 While the printer has placed the Bassus Generalis’s final longa underneath the final note of the cantus, it is obvious in this notation that the final longa must sound earlier, halfway through the cantus’s first semibreve. But even if the Bassus Generalis’s preceding c (a breve in the differently barred Bassus Generalis partbook) were viewed as needing extension until the final note (by adding an additional semibreve), the end result is a composition of 296 (or 297 if one counts a semibreve for the final longa), not 294.

5.15 But this is not the only way in which Bowers’s numeration goes awry. He describes the overall structure as an A:B:A as in the proportion 35:224:35, but in fact, the opening section is actually 36 semibreves in length (16 under C + 20 under 3/2) and the closing 38 (or 39).[81] The overall proportion is 36:224:38 (or 39), which does not match his formula.

5.16 According to Bowers, “the alternating passages of tactus equalis and tactus inequalis (duple and triple time respectively) exhibit in aggregate the ratio 1:1, arising from the manner in which the formula 72 x 3, generating the number 147, determines the total number of semibreves under each mensural disposition.” Leaving aside the Sonata’s unique central section in blackened triplets, the total number of semibreves in the piece under the mensuration 3/2 is indeed 147; but the number of semibreves under C is 125 or 126, depending on how one wants to count the final longa. But even leaving the final longa aside, the number is 123.

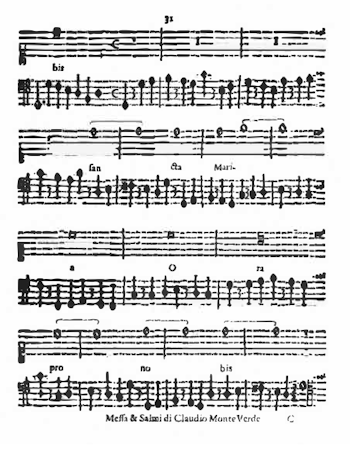

5.17 However, Bowers does not use mensuration as the determiner of his number of semibreves, but rather tactus aequalis and tactus inaequalis, which raises the question of which form of the tactus describes the performance of the central section, in which blackened triplets are notated under C. Bowers actually misinterprets the notation of this central section, though he is not alone in this regard. In fact, blackened triplet notation was the single most confusing notation to theorists in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, and it’s no surprise that about half the modern editions of the Sonata interpret it wrongly, as Bowers has, and about half understand it correctly.[82] The correct interpretation, as demonstrated by the notation itself in comparison with blackened triplet notations in Monteverdi’s Orfeo and in Frescobaldi, consistent with several early seventeenth-century theorists, is that the passage is one of diminution—i.e.,a blackened semibreve sounds as a minim, which is duply divided, and all blackened notes as well as rests at every rhythmic level must be interpreted as sounding one level smaller in the rhythmic hierarchy.[83] This relationship can be seen in the Cantus partbook, where the vocal part and Bassus Generalis are printed, as mentioned above, in score (see Fig. A.8).

5.18 The measure preceding the triplets is in undiminished 3/2 and represents two tactus inaequalis (the second one syncopated by the blackened semibreve). What appear as triplet quarter notes after the C in the Bassus Generalis are actually “blackened” minims, equivalent to quarter notes, the three to be sung in the same duration as two quarter notes under C. The two triplets under C equal a single void semibreve under C elsewhere in the Sonata, and thus a single tactus aequalis. The barring in this version differs from that of the Bassus Generalis partbook where the triplets begin after the barline concluding the 3/2 passage. The Cantus part in this passage is notated in void breves and semibreves, twice the length of the typical Cantus notation elsewhere in the Sonata, and therefore also requires diminution, which the singer would have automatically done in following the director’s tactus aequalis under C.

5.19 Bowers, however, ignores this diminution, counting the passage as 24 semibreves under C. Now, if one were to count the semibreves in this passage as semibreves regardless of whether or not they are diminished, there are indeed 24 semibreves under C, which, if added to the 125 or 126 semibreves under C Monteverdi notates in the rest of the piece, yields 149 or 150, though Bowers would reduce that to 147 by eliminating those pesky extra semibreves in the Cantus part. On the other hand, if one counts the beats sounding as blackened semibreves (i.e., diminished breve units) in this passage, then their number is 12, resulting in a total of 137 or 138 semibreves under C.

5.20 This is where the question of tactus aequalis and tactus inaequalis becomes critical to the analysis, for the tactus is not a count of note values, but of performative, i.e., sounding, beats. Under Bowers’s interpretation of this central passage, the beat is a tactus inaequalis, as Zacconi argues, comprising in modern notation groupings of three minims, raising the quantity of tactus inaequalis in the piece to 171, not 147.[84] On the other hand, if the tactus of this passage is aequalis, consistent with its mensuration under C, then the notation must be one of diminution, with two triplets of diminished minims for every sounding semibreve (i.e., diminished breve unit), resulting in a total of 12 for this passage and 137 or 138 for the Sonata as a whole. Thus, it is not possible for Bowers to achieve his 1:1 semibreve ratio counting either notated semibreves or sounding semibreves.

5.21 The notation of the central passage is unique not only within the Sonata, but in the entire Vespers, though, as noted above, it is used in Orfeo and elsewhere as a notation of diminution.[85] Bowers admits that in his interpretation the notation of this central passage results in the same sounding effect as the passages under the mensuration 3/2. His explanation for why Monteverdi notated the central passage in this unique way is so that he could achieve the 147 semibreve equality Bowers claims. The argument is wholly circular, and does not even yield the result he seeks, as demonstrated above.

The sacri concentus

5.22 Bowers, unfortunately, generates a thicket of inconsistencies, self-contradictions and misconceptions in trying to deal with the sacri concentus. He seems wedded to the premise that there can be no difference between a liturgical ideal as represented in the 1568 and 1570 reformed Roman breviary and missal (as well as subsequent revised editions), the Caeremoniale Episcoporum of 1600 (as well as subsequent revised editions), and actual liturgical performance as we find it represented in practical publications and descriptions of ceremonies. Bowers seems fixated on the notion that apart from special courtly traditions, liturgical performance cannot deviate from the liturgical ideal articulated in official church publications, which results in some bizarre conceptions with regard to Monteverdi’s 1610 Vespers, the first of which he formulates as a set of questions:

Why … did he [Monteverdi] choose to generate the illusion of an apparent elaboration upon a single, overarching but purely notional service of festal Vespers, illicitly interrupted and immensely extended? And what caused him to think of the calculated intrusion of the sacri concentus piecemeal between the psalms (albeit ordered in merely the crudest manner available, by rising number of parts) as a felicitous means of creating this illusion? Certainly the liturgy for festal First Vespers as authorized by the principal service-books offered no legitimate opportunity for the insertion at these points of such extraneous material.[86]

5.23 Bowers deals with the question of the sacri concentus and their interspersion between the psalms at some length, as we will discuss presently, but at the moment we skip to the conclusion of his argument, which ties into the paragraph quoted above. After relating the Vespers (which begins with a reworking of the Orfeo toccata) to the opera as equally displaying “a grand scheme of rational and all-inclusive narrative order,” and declaring that both “should be perceived as bearing a common temporal of orderly linear disposition”—general propositions with which we agree—Bowers goes on to describe that order as it pertains to the Vespers as “purely cosmetic”:

His volume was indeed never anything other than an aggregate of discrete and unconnected pieces, its messy inconsistencies veiled behind a cunningly contrived façade of temporal linearity and intellectual cohesion.[87]

5.24 How such a “grand scheme of rational and all-inclusive order” could be filled with messy inconsistencies, sacri concentus that possess “no envisaged propriety within any Vespers service” and a “kaleidoscopic heterogeneity and patently incoherent diversity of forms, styles, and scorings”[88] is itself an inconsistent, incoherent argument whose self-contradictions we are at a loss to reconcile. The only explanation Bowers offers seems to be that Monteverdi wished to create some kind of illusion. But Bowers doesn’t attempt to answer the obvious question why Monteverdi would “choose to generate [such an] illusion” in the first place. Instead, we receive a non-answer, not even a definable speculation: “Conceivably, in this procedure he was exploiting a particular pattern suggested to him by standard custom and practice in the Gonzaga household cappella.” This is justification by fantasy; moreover, such imagined customs and practices that there might have been in the Gonzaga household cappella hardly seem relevant to a publication dedicated to the pope and marketed widely in Italy and northern Europe and clearly put to practical use.

The role of the sacri concentus

5.25 Now let us turn to the question of the role of the sacri concentus in Monteverdi’s print. Based on the wording of the title page and the non-liturgical texts of the four motets (the Sonata uses a single phrase from the Litany of Loreto), Bowers concludes that the sacri concentus, despite their positioning in the print, can’t have anything to do with even an “illusory” Vespers service. Nevertheless, he examines the arguments that have been made in favor of their inclusion in an actual Vespers service, but refuses to accept any analogy to the use of the organ as described in the Caerimoniale Episcoporum: “It appears, meanwhile, that there survives no evidence suggesting that at this period such substitution could be made by any musical means other than the organ.”[89]

5.26 Bowers subsequently quotes the passage from the Caeremoniale also quoted in our main text, par. 17.10, requiring a singer to recite in an intelligible voice a text which the organ is replacing (with an improvisation on the plainchant). But at this point he immediately makes a leap again to imaginary practices at the Gonzaga court:

Hereby there was offered due acknowledgement of the legitimacy, under certain circumstances, of thus replacing the repeat of the plainsong antiphon with music of comparable scale but somewhat greater elaboration, albeit only for organ and perhaps also a solo plainsong voice; and with the private chapels of the sovereign nobility, such as those within the palace of Mantua, probably there was little to inhibit regular festal application of such a practice at the two major offices of Matins (as certainly as permitted at neighbouring Santa Barbara) and Vespers. Consequently, it appears wholly probable that this custom was known at the Gonzaga chapel at Vespers on greater feasts, so providing Monteverdi with a practical template to follow in his published collection, in accordance with which, one by one following each psalm, he could make artificial intrusion of five of the non-liturgical pieces which he had decided to include within his showcase of sacred music.[90]

5.27 For some reason we cannot fathom, Bowers feels again the need to justify the succession of pieces in Monteverdi’s print on the basis of some kind of fantasized Mantuan precedent, even though the collection does not even mention Monteverdi’s position at the Gonzaga court. Moreover, he had just emphasized that “there survives no evidence suggesting that at this period such substitution could be made by any musical means other than the organ” and rejected suggestions by Whenham and Kurtzman of other seventeenth-century evidence regarding the use of motets in Vespers on the grounds that none of these “relates to Mantua and little refers to any location at all at a time antedating 1610.”[91] We are again confounded by the self-contradictions. (For our arguments regarding the sacri concentus, see the final portion of our main text, starting with par. 17.9.)

5.28 Our critique of Bowers’s articles has involved an exhausting, sad, and disturbing journey. We do have other disagreements with Bowers, but these are not of enough importance to the main issues to prolong further our discussion. Now, then, would be the time and this the place to summarize the findings presented here, but we will forgo such a summation. Instead, we will limit ourselves to remark on what virtually all of our readers understand: history is the accumulation of the research and writing of many different individuals. And even though our perspectives on what we consider important to research and commit to writing change over time, and we all make errors of various kinds—hopefully corrected by ourselves or others—what makes our historical contributions viable is not only our own research skills, methodologies, and integrity, but the trust we can place in the integrity of the information and history provided by others on which our own work is built. That integrity requires that conclusions follow from the evidence—even though the evidence can never be complete and is at times not entirely clear—not that the evidence is manipulated or distorted to achieve a priori or “original” conclusions. Scholarly methodology—our methods for searching, uncovering, and evaluating the truth as best we can know it—is of critical importance in a global society massively invaded by deliberate obfuscation, disinformation, falsification, and outright lying from so many sources and directions. Scholarly methodology must be the model and antidote for how we struggle to restore some sense of integrity to our societal relations. We do not pursue our investigations in a societal vacuum. We invite our readers to consult the Bowers articles that prompted this essay and to judge for themselves whether we have been fair or exaggerated in our rebuttal and whether these articles merited the trust that publishers placed in them and would render them viable and useful to others.

Figures

Fig. A.1. Bowers, “Claudio Monteverdi and Sacred Music,” 334, plate 1

Fig. A.2. Crucifixion with images of Mary and Saint John, Magna Domus, Sala di Sant’Alberto

Fig. A.3. Monthly salaries of the musicians at court, August 1589

Fig. A.4. Monthly salaries of the musicians at court, 1592

Fig. A.5. Monthly salaries of the musicians at court, ca. 1603–8

Fig. A.6. Musicians at court and their monthly salaries, 1606–8, a reconstruction

Fig. A.7. Claudio Monteverdi, Cantus partbook, Sonata sopra Sancta Maria, conclusion

Fig. A.8. Claudio Monteverdi, Cantus partbook, Sonata sopra Sancta Maria, excerpt