The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 30 (2024) No. 1

Music, Business, and Belonging in the Antwerp Salon of Leonora Duarte (1610–1678)

Elizabeth Weinfield*

Abstract

In the seventeenth century, Antwerp’s merchant class primarily comprised Jewish immigrants from Portugal and Spain; they were business savvy, exploiting familial, cultural, and linguistic connections to facilitate deal-making. The converso Duarte family forged networks that allowed for survival despite tenuous circumstances, and ultimately intellectual and professional flourishing; the home functioned as a semi-official space for these convergences. Business letters exchanged between members of the family and their royalist counterparts, such as the diplomat Constantijn Huygens, also shed light on the importance of the Duartes’ home as a place of performance, where women made music in the salon. Music facilitated business while establishing trust and friendship across racial, linguistic, and religious boundaries. The Duartes exploited the exclusivity of their social-religious community to subvert the notion of nationhood, at once challenging the position of the converso merchant as a wandering, nation-less minority and complicating a gentile claim to national heritage.

2. The Duarte-Huygens Correspondence: Extending the Salon Space

4. Music and the Performance of Religion

1. Introduction

1.1 On December 27, 1648, Gaspar Duarte (1584–1653), a converso jewel merchant, art collector, and appraiser in Antwerp wrote a letter to his friend, the poet and diplomat Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687). In it, he professed, “We have been very honored by your visit and grateful for the music sent; my daughter Leonora will sing [the songs].”[1] Huygens had recently brought the Duartes some of his compositions, a collection of pieces for solo voice and basso continuo in Latin, Italian, and French from his Pathodia sacra et profana (Paris, 1647). It must have pleased Huygens to know that the celebrated musician Leonora Duarte (1610–78), Gaspar’s oldest child, would perform his music, likely accompanied by members of her musically talented family. Just months before Huygens’s visit, William Swann, an English captain in the Dutch army, had recounted to Huygens his own experience of hearing the Duarte family perform: “For Monsieur de Warty [sic] and his daughters I have heard to the fulle. Indeed they make a fyne consort and harmony for luts, viols, virginals and voyces. I doubt not but you will fynde great contentment by hearing them.”[2] Swann was not alone in his admiration. Moved by the beauty of the city of Antwerp and the music he heard there, English diarist John Evelyn had noted seven years prior that “I was invited to Signor Duert’s [sic], a Portuguese by nation, an exceeding rich merchant, whose palace I found to be furnish’d like a prince’s; his three daughters entertain’d us with rare musiq, vocal & instrumental, which was finish’d with a handsome collation.”[3]

1.2 This testimony joins over a dozen surviving letters to, from, and about members of the Duarte family affirming that listening to the musically talented Duarte daughters perform at their palatial home on Antwerp’s Meir was a widely celebrated activity for travelers. The correspondence between Gaspar Duarte and Huygens, Gaspar’s close friend and associate, is particularly illustrative of the various ways in which music held meaning for the Duarte family. Many letters contain passages that pique the interest of the music historian, as they bring to light evidence of music’s presence in the domestic sphere. For example, on November 21, 1640, Gaspar wrote to Huygens:

Concerning the music, I would appreciate having a couple of these beautiful Italian and French airs; I believe that they were presented to you by a nobleman musician, by the name of Varenne.… We sometimes have a little music ensemble at home, like the one we formed for Miss Anna Roomers [sic]; namely, three instruments which are particularly suitable for three ladies, the spinet, the lute and the viola bastarda, and me the third treble on the violin, and for the voices: one lute and one viol for the two trebles with my two daughters singing, and sometimes two trebles with bass which I sing, either with the spinet or theorbo, for small madrigals of the book.[4]

Another of Gaspar’s letters to Huygens, dated January 9, 1641, contains the following passage:

Sir, thank you for the two songs, the one in Italian and the one in French, the latter of which, although no air de cour, is nice and good. In return I am sending you two other Italian songs, but I could not find the Occhi belli guarciri which I had also mentioned; I will send it later.[5]

And a few months later, in a letter to Huygens of April 21, 1641, Gaspar added, “Regarding the two pieces of music that I sent you earlier, only the upper parts were included. I am sending you here three others in two parts in Italian that my two daughters have been singing.”[6]

1.3 These citations provide fascinating details about the music-making practices of the Antwerp Duarte family—who had immigrated from Portugal in the sixteenth century and converted to Catholicism in the wake of the Inquisition—and Huygens, one of the most important figures in early modern diplomacy and a businessman who, like Gaspar, had a hunger for high art. In their letters we glimpse details about Gaspar’s oldest child, the composer Leonora Duarte, who was highly accomplished on the harpsichord, lute, viol, and in counterpoint,[7] and about the musical practices of some of her younger siblings, also musically prodigious.[8] Through these letters we learn of the “musique domestique” that Huygens heard the Duarte children perform at home.[9] We also learn that the family’s consort (“petit concert d’instruments”), which contained a lute and spinet, was a space for experimenting with the polyphonic performance technique of viola bastarda. We observe, as well, reference to the singer and composer of airs, Bernard de Varenne (“La Verane”), who visited Huygens in Holland in January 1640.[10]

1.4 Passages such as these are important source documents providing testimony of the sort prized by musicologists for their insight into music-making in the domestic sphere. The exchanges shed light on the importance of the Duartes’ home as place of performance, a destination that became a well-known port of call for traveling diplomats and literati—not only for Swann, Evelyn, and Huygens, but also the composer Nicholas Lanier; the natural philosopher and writer Margaret Cavendish; and Cavendish’s husband, William Cavendish, a patron of music and connoisseur of instruments. The exchanges also provide vital testimony about performance practice, the circulation of musical knowledge, and organology. They regularly take on a life of their own in the scholarly literature—they persist in citations and recopied citations, quoted in isolation from their original contexts.

1.5 The following study will analyze the Duarte–Huygens correspondence to illuminate music’s potential for uncovering how cultural and domestic forces converged for the Duartes, an ethnically Jewish family living in the shadows of the Inquisition, and how music positioned their home as a shared space for the business and artistic elite. The musical exchanges between Gaspar Duarte and Huygens appear in letters that are primarily concerned with their business dealings; these are documents that reveal that cultural and professional pursuits were interlocked. This is a contingency to take seriously, for it encourages further examination into how exactly music related to business for the Duartes, and how music helped facilitate what might have otherwise been complicated social and political transactions. One of the most crucial places where music happened, as reported in the letters, was in the Duarte salon, a place of solace and privacy that Marika Keblusek has recently argued “ensured [for] the visitor an informal, protected atmosphere, where a shared language of cultural pursuits—of music, art, literature—could be exploited to forge other, politically charged, bonds.”[11] Music, particularly conducive to socializing, facilitated and legitimized business and cross-cultural networking and, more crucially, functioned for the Duartes as a specific means to establish trust and friendship across racial, linguistic, and religious boundaries.

2. The Duarte-Huygens Correspondence: Extending the Salon Space

2.1 Private residences such as merchants’ homes served as cultural and intellectual repositories in the early modern world;[12] the Duartes, conversos of Judeo-Portuguese descent, were jewel merchants and art dealers whose function in sophisticated society aligns with what Cecil Roth deemed “an essential factor of cultural activity in the Renaissance.”[13] In other words, Jews were particularly important to the early modern social economy, as the purchasing and selling of wares was a shared concern of the merchant class, predominantly Jewish in the Low Countries. Mercantile transactions often occurred in the home, spaces where collections could be viewed extensively.[14] The merchant class in Antwerp primarily comprised Jewish immigrants from Portugal and Spain; they were unquestionably business savvy, consistently exploiting family connections and the familiarity of shared culture and language to facilitate deal-making as a means of survival, sometimes at the expense of remaining squarely within the fairly compact Judeo-Portuguese world from which they came. In the specific case of the Duartes who resided in Antwerp, a city increasingly anti-Semitic throughout the sixteenth and into the seventeenth centuries, their uncertain status as conversos, combined with their participation in the elite practice of music, facilitated interactions with segments of society that may have otherwise proved untenable.

2.2 Gaspar established a large international community that came together at his family’s house concerts and which his son Diego II (1612–91) continued to cultivate after his death. The Duarte home attracted English court musicians such as Nicholas Lanier[15]—who were themselves in exile in Antwerp during the English Civil War—and even royalty, such as Mary Stuart, who may have visited the city on her way to Spa.[16] Like Lanier, both Mary Stuart and her brother Charles Stuart (later Charles I) stayed in the Duarte home while in Antwerp, even though the English community entertained them elsewhere during their stay.[17] Margaret Cavendish grew to know the Duarte sisters and was entertained by their singing in their home, and at her own in the former Rubenshuis down the street.[18] So important and celebrated was the family’s role as artistic patrons and specialists that Huygens once deemed the Duarte residence “Antwerp’s Parnassus,” comparing the mythological mountain that was home to the Muses to the space that benefited from the family’s ability to draw together an array of guests for the purpose of sharing culture.[19]

2.3 Letter writing, like dining, music, and other aspects of daily life, bound communities together while they were apart, or away from the home.[20] The space created in letters became an extension of what Keblusek has aptly termed an entrepôt—another zone of sharing and belonging.[21] Henri Lefebvre identifies the early modern urban space as a vessel particularly conducive to these convergences, due to a shift in the social perception of spatial utility and purpose in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, “a harmonious whole, as an organic mediation between earth and heaven.”[22] Musical congregating established the Duarte home as a container of both social and economic processes and illuminated the salon as the sort of space Lefebvre has argued is connected directly to capitalist processes due to its multiplicity of meaning: such “diverse breeds of capital and of capitalists, along with a variety of overlapping markets—commodities, labor, knowledge, capital itself, land—are what together constitute capitalism.”[23] Letters extended this complex space: though not themselves contained places, they strengthened the business connections and social bonds that were built in the home and, in Gaspar’s case, reinforced the professional capital-building facilitated therein.

2.4 Gaspar Duarte’s letters are evidence of the fact that his networks were vast, an exceptional fact considering his subordinate position as a converso in Catholic Antwerp. As he wrote to Huygens about music, he grew his jewel business, his reputation as an expert in fine art, and his knowledge of instruments while simultaneously serving as the consul of the Portuguese Nation in Antwerp in the 1640s.[24] The Portuguese Nation (Nação) comprised conversos whose heritage connected them to the Iberian Peninsula during the Inquisition; as I discuss below (Chapter 5), formal organization permitted civic officials to closely monitor this population of recent immigrants. In some ways, the Portuguese Nation functioned as a social embassy, in which a sense of belonging was built on the shared experience of exile and unity amidst persecution. Although many merchants of Jewish extraction converted to Catholicism, some also remained steadfastly Jewish in identity and practice, despite edicts to the contrary. For this reason, the Jewish-Portuguese community, and especially recent converts, were considered suspect, a population marked as different; this threatened their ability to travel freely as citizens (a problem not experienced by their gentile counterparts).

2.5 While the Duartes belonged to this community of exiled conversos, their networks were extensive and they forged bonds with English Royalists—as mentioned above, in exile themselves in Antwerp during the English Civil War. Exile is a progenitor of social unification in Jewish histories at least as far back as the fifteenth century. Following the edict of expulsion from Spain in 1492, conversos in Castile were collectively suspected of continuing to “judaize” after their mass conversion to Catholicism. The Spanish Catholic church closely monitored the converts, who together never really integrated into either the Christian or Jewish communities; this group was subject to a new and intense hatred—an ethnic anti-Semitism—in which, as Renée Melammed describes, “the conversos and their descendants, or nuevos cristianos, bore the brunt of local anger.”[25] Similarly, despite the inferior political position that converso merchants held in Antwerp, no other group provoked as much existential anxiety amongst non-Jewish merchants; the conversos were large in number, multi-generational by the seventeenth century, and were persistent and successful in their work and trade.

2.6 The Duarte–Huygens correspondence suggests that the home functioned for the Duartes as a semi-official space for the convergence of exiled individuals, and that music-making enabled such interstitial and interracial dependencies between groups.[26] The Duartes’ musical abilities served to bring together and unify disparate entities and diplomatize what could otherwise have been, at best, fragile transactions between a Judeo-Portuguese family and their non-Jewish counterparts in post-Inquisition Antwerp. By extension, the correspondence exposes the intersection between women’s roles as musicians and as facilitators of business in the domestic spaces of early modern Antwerp, one not yet thoroughly examined in the musicological literature. The discursive uses of music in non-professional contexts by members of a converso merchant family alongside the Jewish mercantile community and the gentile elite illuminate the home as a shared space, the salon taking on aspects of a business space within the world of conversation and culture sharing.

3. Music and Business

3.1 Throughout their forty-year correspondence, Gaspar and Huygens used art, music, and the traffic of musicians and fine instruments to forge an international network between countries that were sometimes at war,[27] a network that granted Gaspar the connections he needed to distinguish himself as a businessman in a competitive industry. Huygens, who represented the House of Orange, was perhaps the Duartes’ most important business intermediary, particularly as he lived in and operated from the Low Countries during the Commonwealth of England (1649–60).[28] Gaspar’s and Diego’s letters to the diplomat—in Dutch, English, and French—reflect the ease with which the men navigated between national boundaries and call attention to the fact that the Duarte salons also must have been multilingual events.

3.2 Over the years, Gaspar engaged Huygens in discussions of matters entirely unrelated to the jewel business, but which served to increase a mutual sense of trust and maintain a groundwork for other interactions. Gaspar sometimes helped his friend with personal matters; in 1641, for example, his interventions proved crucial to the sale of Huygens’ country home just outside of Antwerp.[29] On January 9 of that year he writes, “I will do all that may be possible for you and your house,”[30] and again on April 21, “as for the sale of your house, I will conduct the business with industry and reputation as best as I can.”[31]

3.3 Musical discussion with Huygens helped to pave the way for one of the most significant business transactions the Duartes completed in their career as jewel merchants: the London sale of a priceless brooch destined for Mary Stuart, daughter of Charles I, on the occasion of her marriage to William II of Orange in May 1641.[32] Gaspar had first taken his oldest son, Diego II, to London in around 1632. Both men integrated into London society and, with Huygens’ help, swiftly moved into court circles;[33] within two years Gaspar’s commerce in the city was thriving.[34] In 1634 Gaspar and Diego were naturalized as English denizens and given status as residents, which facilitated trade.[35] In 1635 Charles I appointed Diego his “Jeweler in Ordinary”; Diego was now the king’s personal agent for procuring gems.[36] After Gaspar’s death, Diego brought his brother, Gaspar II, along with him on business trips to England and continued the family’s work with established clientele.[37]

3.4 In this capacity, Gaspar and Diego were the intermediaries between the English and Dutch courts as they and Huygens negotiated the sale of a brooch for Mary Stuart on behalf of Huygens’s employer, the Stadholder Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange.[38] Diego identified the jewel, a piece that was valued at the exorbitant price of 80,000 guilders, in London.[39] The plan was for him to bring it to Antwerp to show Huygens, while a facsimile was sent to the Stadholder through a messenger.[40] Gaspar remained in Antwerp and facilitated the deal in letters. On March 24, 1641, he writes to Huygens that the ambassadors of Holland had finally seen the jewel—and were very satisfied: “Their Excellencies the Holland ambassadors saw it in London, and also told His Highness about it, because they were so delighted to see so magnificent a piece. For the four diamonds in combination have the impact of a single diamond valued at one million florins.”[41]

3.5 In earlier letters initiating these business discussions Gaspar also engaged in musical conversation, for example mentioning some unidentified French and Italian airs that he hoped Huygens would send him—one of the passages quoted above (par. 1.2).[42] As Timothy De Paepe has noted, these musical details provide an entry into, and a transition away from, the thornier, anxiety-provoking, business matters that also drive their correspondence.[43] As Gaspar delicately describes the value of the jewel to his friend, he also poses questions about music meant to encourage response: the discussions that ensued paved the way for more serious dealings and ensured the progression of the lengthy negotiation process. This culminated in Huygens forwarding Gaspar payment, which the latter recorded receiving on May 9 of that year.[44] Music had not only forged neutral territory and maintained trust, but ultimately laid the groundwork for the sale.

3.6 As with performances in the Duarte family home, which brought various interlocutors into the family orbit, music functioned in their correspondence to enhance business dealings. Gaspar’s and Huygens’s letters testify to an investment in social capital. Following their exchange, the Dutch Stadholder was convinced by Huygens to complete the purchase, and the jewel was given to the nine-year-old bride; it features prominently on Stuart’s bodice in a marriage portrait of the royal couple by Van Dyck from the same year (Fig. 1). The discussion of music in the letters engaged those in the Duartes’ orbit, leveraged power, and ultimately helped determine professional success. The letters concerning the whereabouts and value of the jewel present what Lisa Jardine deems an “intriguing picture of a luxury object whose value … is being established by reference to its desirability in two locations.”[45] The story told in these letters is one of material culture, in which knowledge circulates in channels outside the confines of established spaces, in this case between two “fashionable societies”: those of the recipient and of the individuals making the sale.[46] The Duartes, making the sale, had arrived at the pinnacle of society at this juncture, despite the racial and religious prejudices against them. Gaspar’s musical connection to Huygens was an authentic point of contact based not solely on business dreams, but on a genuine interest that attracted the likeminded and which served as a basis for constructing advantageous alliances.

3.7 By 1648 music had become business for the two men. That year, Gaspar facilitated Huygens’s purchase of a Couchet harpsichord after an extensive correspondence with the Ruckers-Couchet firm, neighbors of his in Antwerp.[47] Gaspar took an interest in instrument building and kept up with the developments of many makers, sometimes contributing information based on his experience as a musician. Knowing of his friend’s expertise, Huygens sent Gaspar in pursuit of a particular type of instrument for his own collection, and must have been delighted when he received word, in a letter of March 5, 1648, that his friend had located “a harpsichord with one full keyboard reaching to the lowest G.”[48] Gaspar is likely speaking about the Couchet model III, which was a large single manual harpsichord the firm produced at the time. The correspondence details an essential fact with regard to the instrument’s construction, namely that Couchet’s single-manual harpsichords usually had a range of four octaves from C with a short-octave bass—in other words, that the low note, if not a commonly-used bass note, would have been tuned down to a lower, more useful pitch, fulfilling the octave yet leaving some pitches out (hence “short octave”). As late as 1644, Couchet’s partner, Andreas Ruckers, is known to have been making these single-manual harpsichords (based on the older Couchet model II) with the range indicated in the above correspondence (Fig. 2 depicts a similar instrument).[49] Indeed, further letters between Gaspar and Huygens reveal that Couchet had already made four such extended-range instruments by 1648, chromatic from GG (model III). For example, Gaspar writes, “The length of the large harpsichords is around eight feet; at choir pitch with three registers, there are three different strings, that is to say, two strings at unison and one at the octave; all three can be played together or each string alone.”[50]

3.8 The instrument that Huygens ultimately purchased was the Model III, an extended single manual without the four-foot, with a range of FF to d′′′, an unusual range compared to that of other Model III instruments being made at the time.[51] The low F, however, is indicative of the fact that the harpsichord in this configuration could easily have been used to accompany the viol, as F is a very common key employed by seventeenth-century viol composers, Gaspar’s daughter Leonora chief among them. Gaspar’s familiarity with the early days of the Ruckers-Couchet firm and expertise in the mechanics of the instruments are likely what encouraged Huygens to seek his council: Huygens’s purchase of the very sort of instrument that Gaspar procured is proof that he trusted his advice and speaks to music’s role in fusing the business and social worlds of the two men.

4. Music and the Performance of Religion

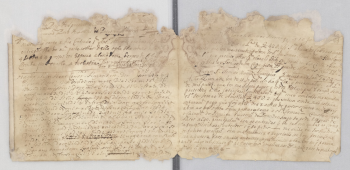

4.1 Gaspar’s multifaceted connection to Huygens was shared by other members of the Duarte family and continued into the next generation; two of Huygens’s sons were close with the Duarte children. After Gaspar’s death, Diego, in particular, continued to cultivate an intimate musical connection with Huygens. In 1684 Diego sent Huygens some of his own compositions, seeking the diplomat’s approval. He also sent drafts to at least two of Huygens’s children, the mathematician Christiaan Huygens (1629–95), and Susanna Huygens (1637–1725).[52] A letter from Diego to Huygens, dated January 1684 (Fig. 3), explains his having set a collection of psalms from the Paraphrase des Pseaumes de David of 1648 by Antoine Godeau (1673–85).[53] After opening with a friendly inquiry about his friend’s health, he writes: “With regard to the paraphrases of Antoine Godeau … although it was my intention to set only a few to music, I think it is a subject so divine and suitable, insofar as they are psalms, to praise and thank God, and especially your encouragement … [letter is damaged from this point forward]”[54]

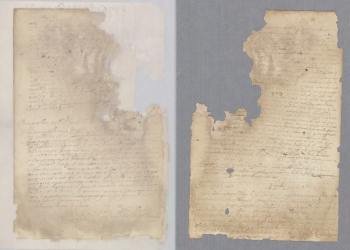

4.2 On January 6, 1687, the year of Huygens’ death, Diego writes another letter to his friend on the same subject (Fig. 4). This one, like the above, is greatly eaten away and missing many words, but within its remains we witness Diego revealing to Huygens that he has dedicated the Godeau settings to him:

I have taken the liberty of dedicating it to you, with the wish that you will have at least some of the satisfaction with this that it gives me … so that my time and my work have not been in vain. You will forgive me this freedom, with which I wish you a happy new year and a future of many to come.[55]

4.3 Diego’s Psalms to Huygens are a paean to his father’s close friend and colleague, a man who was a key figure in seventeenth-century cultural diplomacy and whose connections had greatly sustained his family’s business and ensured their ability to give full purpose to their cultural pursuits. The works also acknowledge a man known for helping the careers of many young musicians and painters in the 1640s and 1650s, even while immersed in the political responsibilities associated with maintaining the reputation of the House of Orange after William II of Orange died in 1650.[56]

4.4 Huygens’s own compositions betray influences from England, France, and Italy: he was influenced by a variety of styles from the Continent as well as the British Isles, refashioning them into a quintessentially Dutch style that reflected the contemporary state of music in Antwerp. Diego may have taken the idea to set Godeau from Huygens, as De Paepe has suggested, likely influenced by the worldly man’s knowledge and fusion of musical language. Huygens himself had also set psalm fragments, when he was a younger man.[57] However, as De Paepe explains, while “Huygens, a staunch Protestant, had used the Latin, Catholic edition of the psalms[,] Duarte had used the edition by Godeau, intended for Catholics, but also taken up by Protestants.”[58] Setting psalm texts is a logical choice for one choosing to write liturgical music; yet his doing so also suggests that Diego’s works were intended for the multilingual elite of his circle and were meant to be performed in the home.

4.5 De Paepe notes that “originally Duarte had doubts about setting the psalms to music, but eventually decided that it would be appropriate as long as praising the Lord through song was the purpose.”[59] De Paepe observes in this rationale a similarity to Leon Modena’s defense of Salamone Rossi’s Songs of Solomon sixty years earlier.[60] Modena defended a newness in Rossi’s music,[61] perhaps what Roth might have meant when he claimed that Jews in the early modern period embodied a “cosmopolitan outlook” within the Christian world,[62] or what David Ruderman has described more recently as a kind of humanistic mobility amongst communities of Jewish intellectuals of this time.[63] Where Diego’s modernity was reflected in his musical adherence to Catholicism, Rossi’s music arose as part of a tradition within Italian Jewry of mourning the loss of musical art within Jewish music.[64] Modena wrote about this phenomenon in his Foreword to Rossi’s Hashirim Asher Lishlomo of 1622: “Shall the prayers and praises of our musicians become objects of scorn among the nations? Shall they say that we are no longer masters of the art of music and that we cry out to the God of our fathers like dogs and ravens?”[65]

4.6 Certain aspects of the Jewish liturgy continued to be performed traditionally during Modena’s and Rossi’s lifetime, and while in Hashirim Modena recognizes the poor state of music in the synagogue, he makes clear that things were not always so lackluster. As Joshua R. Jacobson observes, later in the essay Modena makes the argument that Catholic music and ritual practice saw their origin in ancient Israel,[66] thus forging a connection between art music and a Jewish identity. Modena’s and Rossi’s situation in Italy, and their ability to live openly as Jews, differed greatly from that of the Duartes and other conversos in the Netherlands in the second half of the same century. Rather than emphasize the relationship between ancient Jewish and traditional Catholic practices, Diego may have felt compelled to defend his compositional decision within social circles where his ethnic origin was known, as a means of reinforcing his identity as a second-generation Catholic. Referring jocularly to a Sarabande that Diego wrote for the Annunciation, one of the holiest days in the Catholic calendar, Constantijn Huygens’s daughter, Susanna, remarked upon “a devotional (Catholic) song on a Flemish text set by a Jew.”[67] Even while setting sacred music, Diego’s identity was still understood by others as Jewish—an exception to the rule—his religious fervor suspect.

4.7 Diego’s writing of concerted music crucially serves, however, to distance him from the stereotype of the Jew as noise-maker, particularly the creator of Jewish sounds emanating from the home, and which Ruth HaCohen cites as a major tenet behind the music libel against Jews in the early modern period.[68] The association of animalistic noise with Jews presents a complicated historiography in which Jewish cacophony born of the synagogue stands in relief against concerted Christian music. The topos, HaCohen argues, is particularly embedded in the early modern period,[69] and is a phenomenon that Michael Marissen suggests culminates in the eighteenth century. Marissen proposes, for example, that the aria “Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron” and the “Hallelujah Chorus” in Handel’s Messiah are anti-Judaic, partially on the grounds that the “people of Israel” whose destruction is celebrated in the “Hallelujah Chorus” are portrayed in “Thou shalt break them” with an evocation of noisy banter and confusion.[70] By looking at the mechanics of Jewish stereotyping in early seventeenth-century theater in Mantua, Emily Wilbourne, too, has revealed that actors in the seventeenth century understood voice to carry ethnic and social markers distinguishing Jewish meaning; one could enact Jewishness and one might also cover it up.[71] Amidst this soundscape, Diego’s music reflects a covering up, a quest on the part of non-religious Jews for a social emancipation, a material freeing from the binds of prejudice. Music, as Diego wrote to Huygens, “means harmony” (contra noise) and “does not tolerate contradictions within itself.”[72] The musical socializing enacted in the Duarte salon repudiates the anti-Semitic construct of synagogal domestic chatter and instead generates a secular domestic “embassy” in which culture is economy. The specific connection between observation and social status that is encouraged by the semi-public space of the salon is mimicked in the circulation of knowledge in the exchange of letters. De Paepe has suggested that the Duartes used their patronage of art and music to forge neutral territory between Jews and non-Jews;[73] the Duartes’ music-making also negated the construct of the Jewish home as a place of noise and heresy.

5. The Portuguese Nation

5.1 As Gaspar built and grew his international connections, he also maintained connections with Antwerp’s Portuguese community. Like many Portuguese enclaves in the Atlantic diaspora, Antwerp’s primarily comprised Jewish immigrants who had come to the city in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, and who had converted upon leaving Portugal or on arrival in Holland. This community was unified socially under the aegis of the “Portuguese Nation,” a term derived from the Portuguese term nação which was originally applied to groups of traveling merchants from Portugal whose identity remained unified in the diaspora via their shared beliefs or even professional activities.[74] The phraseology connotes a categorization of people by their race.

5.2 The terminology was employed to refer to recently converted Christians, in Antwerp and elsewhere, and grows from language utilized in the Iberian Peninsula during the Inquisition. At the end of the sixteenth century, the term “nation” was used to emphasize the conversos’ supposed ethnic or racial traits, at a time when, as Miriam Bodian notes, “religious suspicions merged with the general configuration of anticonverso thinking, which pointed to the conversos’ tainted blood as the source of their many evils,” and thus warranted categorization.[75] Bodian observes that “there was an increasing use of collective terms like gente del linaje, esta gente, esta generación, esta raza (‘those [people] of this lineage,’ ‘this people,’ ‘this lineage,’ ‘this race’), as well as los de la nación (‘those of the nation’)” to refer to the ethnically Jewish, whether or not they had converted to Christianity.[76] Bodian shows that, while this was first the case with conversos in Castile, this thinking quickly spread throughout the Judeo-Iberian diaspora.[77] It is unclear when the Duarte family converted, but all six of Gaspar’s children were baptized, and many members of the family are buried in front of the altar at their local parish church, Sint-Jacobskerk (St. James), an institution that the Duarte family also supported as patrons at one point, as De Paepe recounts, helping to build “stonework decoration of one of the church porches.”[78] Yet individuals like the Duartes, who openly associated themselves with Catholic enterprises, were not immune from exclusionary regulations that barred “new Christians” from fully participating in religious and municipal institutions, and from joining confraternities and guilds. As Bodian, Jonathan Israel, and others have shown elsewhere, conversos were subject to this segregationist thinking throughout the seventeenth century.[79]

5.3 Recognized as neither fully Catholic nor as Jewish, conversos like the Duartes were therefore living in a kind of bifurcated exile, a liminality that defined much of the experience of European Jewry in the seventeenth century.[80] The threat of expulsion even after conversion was likely one of many shared concerns among Antwerp’s conversos, whose recent ancestors had, at the end of the fifteenth century, been subject to a mass baptism, lured with promises of safety, then swiftly ordered to leave by the Portuguese king.[81] Although the conversos were legally permitted to stay in Antwerp as Catholics, legislative assurance of their right to remain was tenuous at best. They were a group marked as different—as a population apart. A sense of double identity must have been an intrinsic component of the converso experience in general.

5.4 Within this network, Gaspar was also part of a mercantile community with a deep sense of belonging. He served as the consul of the Portuguese Nation in Antwerp, first in 1641 and again in 1646.[82] Like the Duartes, many members of the Nation were merchants who helped to grow Antwerp’s economy substantially; most of them were also conversos who, whether crypto-Jewish or practicing Catholic, were restricted from participating in the guild system in any way and thus from most trades and crafts.[83] Portuguese Jews in both Antwerp and Amsterdam attempted to build community in spite of this; in Amsterdam, where the Dutch Republic granted Jews religious freedom, community was formed in large part by importing Sephardic rabbis from Italy, North Africa, and the Ottoman Empire, an action that forged a connection to a larger network of Jews in the diaspora.[84] Many leaders of the Amsterdam Portuguese-Jewish community adopted Sephardic surnames as a means of reclaiming this Sephardic legacy as émigrés.[85] Conversos in Antwerp, who could not practice Judaism openly, also discarded their Hebrew names in favor of Sephardic names, and the Antwerp Duartes, originally Abolais in Hebrew, were no exception.[86]

5.5 What we call a foreign embassy today was referred to as a “nation” in the early modern period, such that “nation” is at once a concept, a unifying marker, and a place of convergence. Unity among the nation was partly the result of self-fashioning in exile and in the wake of suffering, at a time when Portuguese Jews had let go of their religious traditions—and only within a generation of the Portuguese Inquisition—and in which, therefore, the Inquisition was crucial to a sense of belonging and to a new “founding mythology.”[87] Gaspar’s involvement in this network even while cultivating business connections outside of it entitled him to a double professional existence as well; part of the nation, and as a member of the Nation, he benefited from an additional community unified by shared experience of past and present and the desire to preserve heritage. These connections proved crucial to the success of his business endeavors.

5.6 Occasionally Gaspar’s letters reveal that, while he cultivated trust on the part of his clientele, he was also acutely aware of the professional activity of other Jewish merchants in the jewel business. His letter to Huygens of April 21, 1641, which discusses the sale of the Stuart gem discussed above, also contains the following information:

I remain greatly indebted to you for the great affection you have shown towards my son Jacob [Diego] Duarte, by tomorrow showing His Highness that beautiful jewel which I mentioned to you previously. And although I understand that Mr. Alonse de Lope has already managed to sell His Highness four other pieces [of expensive jewelry], nevertheless I hope that your particular favor will have the power to be successful in this matter, since this is such an extraordinarily rare piece.[88]

Gaspar may refer here to Alvaro Lopes, a religious Jewish diamond merchant based in London who is known to have advised many Jews who arrived in the city in the seventeenth century, following the defeat of the Spanish Armada. Gaspar’s knowledge of this man’s whereabouts would have positioned him advantageously while conducting business in London, a major hub of the jewel business in the seventeenth century due to the demand for high quality jewels from noblewomen returning from exile who needed them to wear at court.[89] No evidence exists to my knowledge that Lopes and Gaspar ever met or, by extension, that Gaspar had any direct interaction with other Jewish merchants in London that was not purely business in nature. Travelers to London around the time of the Stuart gem sale report having encountered people openly practicing Judaism, many of whom were a part of the mercantile community in the city. Some members of this community are reported to have been religious, some holding services in their homes before the resettlement of the Jews in England in 1655, gatherings that included several prominent physicians and theologians.[90] Like an embassy, these London homes were presumably also destination points for travelers who had recently arrived in England, many of whom were also jewel merchants. And yet, despite their shared occupation, the social circles of these English Jews and that of the Duartes may not have aligned.

5.7 The Duarte home, too, attracted travelers who converged around a shared locus. However, the Duartes’ visitors came together as fellow ambassadors of culture, exemplifying the “correlation between motion, cultural production, and creativity”—the theme of “intellectual mobility” that David Ruderman suggests as a feature of Jewish life in the early modern world outside the boundaries of religious identity.[91] The intellectual mobility that converged in the intimacy of the family home was part of a larger sense of human movement that had offshoots in transnational mercantile matrices across the globe and against which Jewish self-identification and the representation of Jewish civilization became reified in the non-Jewish world.[92] Yet for Gaspar it was not solely these mercantile networks, but music that permitted him to push his business enterprise to the highest level, and cultured conversation that encouraged transnational competition amongst merchants in the Low Countries. Unlike many of his counterparts, Gaspar’s involvement in a gentile world within the nexus of what was primarily a Jewish trade, “[contests and complicates] the borders imposed by Jewish law and Christian society on its Jewish minority.”[93] For Gaspar ultimately to succeed, he had to integrate his family with the gentile world—and yet he could not distance himself completely from the transactions occurring within religious Jewish networks.

5.8 In some ways, Gaspar’s community- and network-building resemble that of his religious cousin Manuel Levy Duarte, also a merchant—a man who was married to Gaspar’s niece Constancia Duarte (ca. 1631–1707), and who lived in Amsterdam where it was acceptable to practice Judaism openly. Levy Duarte’s professional success, like that of so many in his position, relied upon a close network of other merchants of Portuguese extraction. His papers, which survive in the Amsterdam City Archives, are mostly in Portuguese, revealing that the small Amsterdam Judeo-Portuguese community largely conducted business between families.[94] In fact, Levy Duarte was one of the Jewish merchants with whom Gaspar remained in closest contact, likely due to family ties; the other was Levy Duarte’s business partner, jewel merchant Jacob Athias.[95] Levy Duarte would become the executor of Diego’s will and eventually was responsible for the disbursement of the family’s collection of over one hundred paintings.[96] He and Athias traded internationally in Brussels, Antwerp, London, and Paris, but unlike the Antwerp Duartes they did so primarily with other Jewish jewelers, despite occasionally dealing in other trades such as cloth and cocoa, as was typical of businessmen in the seventeenth century.[97] Like Gaspar and Diego, Levy Duarte engaged in profitable trade relationships with contacts in London. Yet, as Gaspar cultivated connections with the House of Orange, Levy Duarte and Athias built a prosperous trade network that depended, as Edgar Samuel has demonstrated, on two customers who worked with them regularly: Luis Alvares of Paris and Olympe Mancini, the Brussels-based Countess of Soissons.[98]

5.9 Levy Duarte’s success was contingent upon his belonging to an ethnic minority within a major trading city, which was connected by language and kinship with similar communities in other major cities. One reason the diamond trade remained a Jewish specialty is due to what Samuels calls the “compatibility of the commercial needs of the gemstone trade with the structure of Jewish communities.”[99] Levy Duarte is a test case that reveals how language, religious identification, and identity-building amidst persecution bind and to some extent insulate and protect professional communities. Traveling internationally, yet maintaining a fixed linguistic identity, Jewish merchants like him (and Athias, and Lopes) connected with their “nations” in foreign cities. As such these communities stood in for sites like Gaspar Duarte’s home—places where both business and belonging converged to create what Donatella Calabi and Derek Keene have termed “social conformations of exchange, reproduction and innovation,” or networks of trust, shared identity, and purpose, where the exchange of commonalities between foreigners leads to success.[100]

5.10 Levy Duarte was limited in his ability to engage in the artistic and musical small talk perfected by the Antwerp Duartes. His letters make little mention of music, although details about the context for music in his life occasionally appear, for example that one of his harpsichords was placed in the landing in his home in The Hague.[101] A reference to the instrument in the inventory compiled after his death reads, “In the portal over the hallway / The harpsichord with its stand.”[102] His writings about art were constrained to business documentation chronicling the collection from Antwerp he would later inherit. In Antwerp from 1691 to 1696, to settle the Duarte estate following Diego’s death, he fully documented his efforts to sell the collection of paintings. The following entry is from his inventory, currently in the archives of the Portuguese-Jewish Community of Amsterdam.[103] It tracks both those sold and those which had not yet been sold at the start of 1693. De Paepe has recently highlighted the end of the entry for Lot 403, which reads (with my bold marks added):

Permigiano junto ao cabinet 1: Maria met i[eu]us kint e Josef …. f200 1: dito ao lado de lucresia contem St ana Cri[s]tus e s’ Jean … f200

(The Parmigianino together with the cabinet[:] 1: Mary with the child Jesus and Joseph … 200 Florins 1: The same [cabinet] beside the Lucrecia contains Saint Anne, Christ, and Saint John … 200 Florins)[104]

Levy Duarte does not write out the names “Jesus” or “Christ” in his letters about art, in keeping with strict Jewish religious practice,[105] in which the name of God is not written down, leaving no possibility that it might be erased. This is in direct contrast with both Gaspar and Diego Duarte’s practice in correspondence, for example Diego’s letter describing his decision to set all of Godeau’s psalm paraphrases, in which “God” is spelled out in full. Gaspar’s and Diego’s business letters are written in many languages—Levy Duarte’s are mostly in Portuguese.[106] And while Levy Duarte, a practicing Jew, engaged in overlapping networks of influence, they converged on the synagogue, a place which, as Samuel observes, “was the social and charitable focus of his community as well as its house of prayer.”[107] Gaspar’s and Diego’s social and—importantly—musical capital allowed the two men to forge networks outside the confines of the Judeo-Portuguese trade network. For the Antwerp Duartes this convergence happened in the home; the salon in which Gaspar and his daughters performed was simultaneously a business space and a zone of shared experience. The music that the Duartes performed for guests served to suture the bonds that Gaspar and Diego built in their business world.

6. Conclusion

6.1 At their home on the Meir, the Duartes used music to construct a community comprising exiled royalists, businessmen, and musicians; their music brought together non-Jewish members of Antwerp society and travelers from elsewhere in Europe.[108] Comingling in the home of a Jewish merchant during remarkable times, these guests were privy to some of the most sought-after musical performances of their day. A sense of ethnic belonging comingled with an outwardly focused inclusivity is expressed in the multilingual aspect of their correspondence. The social and professional networks the Duartes cultivated were wide-ranging. On the one hand, they ensured their survival in spite of tenuous circumstances, and on the other enabled an intellectual and professional flourishing that would ultimately lead to dealing in jewels with the British royal family at a time when Jews in England were a subjugated minority.[109] Gaspar’s correspondence with Huygens highlighted above is evidence that he skirted various constrictions held over the tightly knit community of Portuguese Jewish jewel merchants, many of whom, like Levy Duarte, communicated with one another exclusively in Portuguese, despite having left Portugal two, and in some cases three, generations earlier. The Duartes exploited the exclusivity of their social-religious community to subvert the restrictive notion of nationhood as an ethnic marker. Their consistency and success challenge the position of the converso merchant as a wandering, nationless minority; their home, a destination point for the convergence of music and business, complicates a gentile claim to national heritage. Gaspar’s success bridged the worlds of both music and business, and was contingent on creating, maintaining, and embodying his family’s image as heirs to the literary and artistic traditions of Europe. Their interest in these traditions was not aspirational or bourgeois, to draw on a nineteenth-century term, but involved them achieving a mastery over artistic practice with which they impressed and outshone their peers. Edmund De Waal has written about similar convergences occurring in the salons of the great homes of Jewish merchants along the newly-built Ringstrasse in nineteenth-century Vienna; the steadfast lure of the social environment, De Waal argues, is echoed in the imposing architecture, both interior and exterior defying a society uncomfortable with Jews.[110] The informal concert hall the Duartes created was the ultimate material expression of their consistency and success—a landmark—“certainly not a house for a wandering Jew.”[111]

6.2 The social capital that this converso family built in some sense resembles that of contemporaneous Christian gentlemen merchants and travelers on the Grand Tour, who also used culture as political economy to maintain and establish social bonds. Music was utilized by the English diplomat Robert Bargrave, for example, to provide continuity in his life while on missions abroad, ultimately engendering feats of diplomatic success.[112] Michael Tilmouth observes that Bargrave’s “musical talents seemed to have smoothed the path for him” as a Protestant traveling in Catholic Italy in 1647, quoting from an account in Bargrave’s diary of a meeting with the governor of Siena, Mattias de’ Medici:

Here my litle Skill on the viall appearing to the advantage, because none else could play on it, endangered my playing before Principe Matteo; but waving it as well as I could, I was only heard by his chief Capellan’s who repaid each lesson with Interest, Each affording me the excellency of theyr voices and severall Instruments, as they were peculiarly quallified, and in presenting me divers admirable Songs.[113]

Bargrave’s skill and knowledge of music masked and enabled his own crypto-identity. In his case, as with the Duartes, cultural currency was a family affair—for Bargrave this had been cultivated by his father, Isaac Bargrave, who had been the recipient of a substantial bequest of Italian books and a viola da gamba by his close friend Sir Henry Wotton, English ambassador to Venice.[114] In 1652, as Bargrave returned from Constantinople to England, music helped to facilitate passage when his party were invited to an “abundant Feast,” in Danzig, where it was “bestowed on mee a gallant Banquett of musick, in a consort of a German Viall and Violine, with an Italian Lute and Voice; little inferiour to the best I ever heard.”[115] As it did for Bargrave, music presented common ground for the Duartes and their stakeholders and granted them access to an international community of outsiders.

6.3 Music also permitted the Duartes acceptable interactions with gentiles, which ultimately meant that their place in society extended beyond that of racial signification—remarkable in a climate in which accusations of judaizing could lead to death, as it had for Athias’s father, Abraham, burned at the stake in Cordoba in 1665.[116] Music functioned for the Duartes as a means to legitimize relationships across these social, religious, national, and ethnic borders, much as it would in the Jewish salons of early nineteenth-century Berlin—spaces in which enlightened people peacefully co-existed, devoid of identity-driven segregation.[117] The Duartes’ domestic congregation extended into their letters, and not the synagogue, and thus became a metaphoric space for identity-building and networking that permitted the family, like the liberal German Jews of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, to abandon strict belief and therefore integrate with less effort.[118] Gaspar’s interest in instruments, his musical banter with Huygens, Leonora and his other musically-prodigious daughters, Diego’s French setting of Godeau, and the Duartes’ multilingual letters all betray a certain citizenry of the world. Business and domestic networks were interchanged in a worldly setting in the Duartes’ milieu, and this is reflected in their deeply rooted investment in culture and the business successes that grew out of such fertile soil.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this article were presented at “Historical Performance: Theory, Practice and Interdisciplinarity,” Indiana University, Bloomington, 2019; The Society for Seventeenth-Century Music, Virtual Conference, June 2020; and The Renaissance Studies Association, Virtual Conference, May 2021. I owe enormous thanks to the many colleagues who have read previous versions of this paper and whose commentary made it stronger, chiefly Emily Wilbourne and Timothy De Paepe; also, Rebecca Cypess, Janette Tilley, Tina Frühauf, Jane Gottlieb, Barbara Hanning, Robert Wilson, Jonathan Yaeger, and Jude Ziliak. I also wish to thank Lois Rosow and the anonymous reviewers of this Journal.

Figures

Fig. 1. Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of William II, Prince of Orange, and his Bride, Mary Stuart (later Princess Royal), 1641. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Fig. 2. Andreas Ruckers the Elder, Harpsichord, Antwerp, 1644. Vleeshuis Museum, Antwerp.

Fig. 3. Diego Duarte to Constantijn Huygens, Antwerp, January 9, 1684. Letter Book of Diego Duarte, Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Hs. Arch. 334, No. 682.

Fig. 4. Diego Duarte to Constantijn Huygens, Antwerp, January 6, 1687. Letter Book of Diego Duarte, Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Hs. Arch. 334, No. 682.