The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 28 (2022) No. 1

Martyrdom and the Mythical Phoenix: Quirino Colombani’s Il martirio di Santa Cecilia

Holly Roberts*

Abstract

In the oratorio Il martirio di Santa Cecilia (Rome, 1701), librettist Giovanni Nicolò Benedetti and composer Quirino Colombani merge Saint Cecilia’s Medieval identity with early eighteenth-century religious mysticism. The performance of Cecilia’s ecstatic martyrdom becomes “aural iconography,” a form of religious spectacle comparable to the visual arts, where performed rapture is moved from the private to the public realm. This study provides a new lens for investigating the treatment of saints’ legends in late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Italian oratorios, and demonstrates how saints’ identities were repurposed to serve church and audience needs, and realigned to reflect contemporaneous religious philosophies and devotional practices.

2. Cecilia and Valeriano: the Rhetoric of Religious Conviction

3. Tiburtio’s Conversion: a Sensory Appeal to Faith

4. Music and Mystical Transformation

1. Introduction

An ecstatic woman of holy life, who later died in the aura of great sanctity, was sometimes constrained by the pleas of her companions … to offer a sign and an example of what the harmony of paradise might be. Because she was most humble and did not think that she was more favored than her companions, she used to at first put up some resistance, but then she would do as they desired with good will and a happy soul. And thus, in their presence alone, she used to take into her hands a lute, which she had learned to play when she was very young, and touching the strings, she used to play a song that was both most delicate and most far removed from the melody and the form of songs that we hear on earth: it has been certified by the worthiest people of faith that here on earth such a manner of singing and such successions of harmonies had never before been heard. Now, this woman continued to sing and play for only a little while before she was enraptured, and although she ceased to sing, she continued to play, never once erring in her choice of harmonies. When some time had passed, she came out of her ecstasy and blushed because she had lost touch with the world of normal sensations in the presence of her companions; and her right arm and hand, with which she plucked the strings [of the lute] hurt her somewhat.[1]

1.1 Cardinal Federigo Borromeo’s description of Caterina Vannini’s musical rapture is well known to scholars who have focused their attentions on the devotional activities of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century women religious in Italy. For twenty-first-century readers, Vannini’s story serves as a window into the activities of Italian convents that were concealed from outsiders, while at the same time offering key insights into the broader milieu of religious mysticism that existed in Italy throughout the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. The passage includes a number of allusions that tie Borromeo’s description to literary accounts of musical ecstasy that had been in wide circulation since the late Middle Ages (for example the musical raptures of Saint Francis of Assisi,[2] and the musical rapture of the Virgin Mary recounted in the fourteenth-century Revelations attributed to Saint Elizabeth of Hungary[3]). It is also markedly resemblant to sixteenth- and seventeenth-century iconography, in which saints and music are featured together in representations of celestial rapture (see Fig. 1, for example, Guido Reni’s Santa Cecilia).[4]

1.2 Within the span of a few sentences, Borromeo arouses the reader’s curiosity by constructing an unmistakable resemblance between Vannini and illustrious mystics such as Saint Teresa of Ávila, and legitimizes their experiences by aligning his description of celestial rapture with those previously articulated by ecstatic saints. His description makes it clear that Vannini experienced a moment of rapture, or ecstasy,[5] during which she was overcome by divine love, her spirit momentarily transported to heaven and no longer sensible to the physical world. The story, like many others of the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and early modern era, beautifully elucidates the coalescence of music’s dual roles as antecedent to and consequence of rapture; singing and playing are crucial to initiating contemplation, after which Vannini is pulled into rapture where the music is no longer her own, but a product of the celestial ecstasy.

1.3 Disseminated accounts of ecstasy—whether literary or iconographic—serve as a form of spectacle that forges a performer-audience relationship with the reader or viewer. In these cases, the rapture is a real, lived experience for the mystic and the mystic’s community (the reader or viewer momentarily joining the latter) while also existing as a performed or artificial representation of paramount spirituality.[6] Reading and viewing become avenues by which the outsider looks upon the mystic and may imagine, even vicariously experience, their own divine spiritual union. This same relationship exists between the enraptured mystic and the viewer in musical representations of ecstatic saints in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Musical performances of saintly rapture, then, function as a type of living iconography, viewed by audiences who were immersed in the devotional milieu of meditation, contemplation, and ecstatic transcendence.

1.4 The divine love, mysticism, and rapture that infused Medieval hagiography and late Renaissance literature and iconography were similarly present throughout the seventeenth and into the eighteenth century. In music, these themes were especially potent in the Italian oratorio, where divine love and mysticism became inseparable from the Old Testament stories and tales of saints’ martyrdoms that were features of librettos. By the late seventeenth century, most oratorios did not include an extended plot or dramatic sequence of events, but rather focused intently on saints’ emotions and their spiritual development as they faced opposition to the faith and fought to uphold Roman Catholic ideals.[7]

1.5 In oratorios, core tenets of Catholicism were fused with affective music, the purpose being that performances would teach audiences about the path to salvation by delighting their senses and moving their emotions toward a heartfelt connection with God, Christ, and the Church. This meant that the fundamental nature of the oratorio was predicated upon an amalgamation of old and new: biblical stories and Medieval religious heroes were adorned in fashionable music akin to that heard in the oratorio’s sister-genre, opera, while librettos referenced all manner of contemporary literary, philosophical, and devotional trends, including those that were mystic—even ecstatic—in nature. And so Italian oratorios, particularly those of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, provide a unique opportunity to recognize and consider how in music as well as in literature and iconography, influences of contemporaneous ecstatic devotional practices are exhibited in the representation of saintly figures whose identities were forged long before the documented raptures of Saint Teresa of Ávila or Caterina Vannini.

1.6 In this article I examine a representation of the early Christian martyr and patron saint of music, Saint Cecilia, by librettist Giovanni Nicolò Benedetti and composer Quirino Colombani (ca. 1671–1711),[8] and argue that their depiction of her within the oratorio, Il martirio di Santa Cecilia, merged her Medieval identity with early eighteenth-century religious mysticism. My study consists of analyses of Benedetti’s libretto and Colombani’s musical setting, as both are essential to the rearticulation of Cecilia’s identity and the representation of her as a mystic saint who achieves spiritual union with God by way of a musical rapture. Informing this study is Thomas Connolly’s investigation of the origins of Saint Cecilia’s cult and her Medieval characteristics.[9] Of particular importance is Cecilia’s recognition as a healer or giver of sight, as a converter, and as a mythical phoenix. These traits, each an integral component of Cecilia’s Medieval identity, remain foundational in Benedetti’s and Colombani’s representation of her in the oratorio. New, however, is Benedetti’s infusion of early modern mystic philosophies into his portrayal of Cecilia—a reformation of her saintly attributes that is supported by Colombani’s musical setting.

1.7 As Cecilia is the patron saint of music, the viewer may anticipate a moment in the oratorio akin to the single musical scene within her legend (a newlywed, Christian virgin, singing in her heart, imploring the preservation of her chastity). Yet Benedetti and Colombani do not include this anecdote in the oratorio. Instead, the audience witnesses an interpretation of Cecilia’s musical devotion that more closely resembles the raptures that are detailed by early modern mystic saints and depicted in contemporaneous ecstatic iconography. Cecilia begins the oratorio as a Medieval saint of conversion and healing, but through Colombani’s musical representation of her rapture, she is reborn a mystic, spiritual martyr of the Counter-Reformation.

1.8 I argue that the representation of Cecilia’s ecstasy in this oratorio may be described as “aural iconography,” a musical interpretation of saintly rapture comparable to that featured in religious iconography of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This label presupposes specific types of audience engagement with Cecilia’s ecstasy: it was a moment intended to inspire increased emotion and heightened devotionality in the listener, and perhaps even suggested the possibility of lay religious transcendence, but it was also a moment in which the saint’s most intimate, even sensual, relation with God was placed within the gaze of the audience. Through the act of performance Cecilia’s rapture becomes religious spectacle, drawn from private domain and exposed to public observation. Considering the potent erotic undercurrents of early modern descriptions of saintly rapture, oratorios featuring comparable moments of ecstasy inherently held the potential for similar erotic interpretations. Although primarily a devotional genre, the late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century oratorio was performed at private residences with increasing frequency. In these cases, the possibility for erotic interpretations of saints’ melting at the overwhelming force of divine love, and of their requests for pleasurable torments, may have been even more likely.[10]

1.9 Overall, this study of Colombani’s Il martirio di Santa Cecilia provides a new lens for investigating the treatment of saints’ legends within late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Italian oratorios, not only to determine how saints’ identities were repurposed to serve the current needs of the Church and of audiences, but also to discern how librettists’ and composers’ treatments of their subjects aligned those subjects with contemporaneous religious philosophies and devotional practices. My analysis, though certainly focused on Colombani’s setting, also looks beyond the music to literary and iconographic sources of influence, as these same mediums worked upon audiences to shape their interpretations of the oratorio’s contents. The result is a reading of Colombani’s Il martirio di Santa Cecilia that places the libretto and musical setting within a broader context of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Italian devotionalism.

2. Cecilia and Valeriano: the Rhetoric of Religious Conviction

2.1 Although Giancarlo Rostirolla has contributed an important biographical sketch of Quirino Colombani and compiled an index of his compositions,[11] the composer has otherwise received minimal attention in recent academic scholarship. His oratorio Il martirio di Santa Cecilia was first performed in 1701 in Rome at the oratorio of San Girolamo della Carità, under the name L’ape industriosa in Santa Cecilia.[12] The libretto was written by Giovanni Nicolò Benedetti, about whom little is known. Two additional Italian performances are documented: one in Perugia (1705), and another in Spoleto (1707).[13] The two-part oratorio is written for four voices: Cecilia (soprano); her husband, Valeriano (contralto); his brother, Tiburtio (tenor); and the antagonist, Almachio (bass), prefect of Rome. The piece is scored for two violins, violoncello, violone, and continuo, with violin and violoncello each highlighted prominently as soloists at various points throughout the oratorio.[14] Prevalent among the arias is Colombani’s scoring of unison strings above the continuo. Structurally, Il martirio di Santa Cecilia is reflective of compositional trends in contemporaneous oratorios in that its two halves alternate consistently between simple recitatives and da capo arias.[15]

2.2 By 1701 the protagonist of Colombani’s oratorio, Saint Cecilia, was firmly established as the patron saint of music, even though her legend focuses almost exclusively on the conversion of her husband, Valeriano, and his brother, Tiburtio, as well as on the martyrdoms of all three saints. A single reference to music appears within the first few sentences of the legend: amidst Cecilia and Valeriano’s nuptial celebration, Cecilia joins the festive music in silent singing, and pleads with God to keep her heart and body chaste.[16] This musical detail is minute, yet it became the focal point of late Renaissance and early modern iconographic representations that featured Cecilia. From Raffaello’s iconic depiction of the saint surrounded by perishable instruments of the secular world, to representations of Cecilia as a performer (for example as a lutenist in Carlo Saraceni’s version, as a violinist by Guido Reni, and as an organist in Sebastiano Conca’s painting),[17] the emphasis on Cecilia’s martyrdom was gradually replaced by an underscoring of her association with music, and more specifically musical rapture.[18]

2.3 These varying representations frame Cecilia as a saint who harnessed the power of music to communicate with the heavens. Whether explicitly depicted or merely implied (as in, for example, Saraceni’s and Reni’s paintings), early modern iconography featuring Cecilia habitually exhibits a discernible connection between the saint and divinity—a connection, or even transcendence, that is forged by music. The majority of depictions in which Cecilia is a performer emphasize the moment that she experiences climactic spiritual elevation. Although her internalized singing is now instrumental performance, it is still through music that the contemplative Cecilia becomes enraptured: she looks up toward the heavens or to an angel, her gaze transfixed, her soul transported to a higher sphere. Inherent in these early modern representations, then, is Cecilia’s role as an ecstatic—a holy individual who experiences a sacred coupling with God when her soul is brought from the highest degree of transcendence into a state of rapturous unity.

2.4 The privileging of musical rapture in iconographic representations of Cecilia already constitutes a refashioning of her identity to bring it into accordance with early modern mysticism. No longer were conversion and physical sacrifice the predominant foci of her legend as they were for Medieval readers. Rather, her musical communion with God distinguished her as a mystic akin to early modern ecstatic saints (for example, Teresa of Ávila, John of the Cross, and Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi). Considering the prevalence of seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century images that feature Cecilia as an ecstatic, rapt in the sonorities of heaven—representations that amplify the fleeting account of her silent singing—it is worth considering how this reformation of her identity may or may not be similarly represented in contemporaneous music, and more specifically, in Colombani’s oratorio.

2.5 Colombani’s Il martirio di Santa Cecilia begins after Cecilia and Valeriano’s wedding festivities. Valeriano, anticipating the marriage consummation, soon discovers that Cecilia has already accepted the Christian God as her true spouse and is devoted to a life of chastity. Valeriano’s anger and frustration at Cecilia’s abstinence prompts her to teach him the differences between profane and divine love. Through skillful rhetoric and expressions of religious conviction, Cecilia soon converts Valeriano to Christianity.[19] The audience is later introduced to Tiburtio and Almachio, who reflect upon the atmosphere of animosity between pagan Rome and the growing community of devout Christians. To Almachio, the Christians are a source of aggravation, one he wishes the Roman gods would eliminate. As Tiburtio contemplates the ability of the Christian mind to comprehend suffering as joy, he encounters Cecilia and Valeriano, who blissfully sing of their love for God and their delight in each other’s conversions. Tiburtio, overcome by the presence of celestial music and fragrance, is similarly converted. Almachio orders the brothers to renounce their new faith or be executed, but to Valeriano and Tiburtio death is most welcome; martyrdom will bring them closer to Christ and provide them entry into heaven. The oratorio ends with tearful, yet joyous goodbyes between Cecilia and the two brothers. Cecilia, who has not yet been sentenced to death, must remain alive while Valeriano and Tiburtio are allowed to die and be reunited with God.

2.6 The most significant difference between Benedetti’s libretto and Medieval and early modern renditions of Cecilia’s life is that the libretto ends before Cecilia makes her physical sacrifice in the name of Christianity. Except for this “omission,” the contents of the libretto perpetuate (or, perhaps, preserve) those elements of Cecilia’s identity that were fundamental to the recognition of her saintliness in the early Middle Ages. As in Medieval anecdotes, Cecilia’s silent singing is not of dramatic significance to the libretto plot. Instead, Benedetti includes the events of her life that take primacy within the early Medieval legend and subsequent literary renditions, such as the Legenda aurea (as Giacobo di Voragine’s Legendario was commonly known). Frequently referenced in the libretto is Cecilia’s work as a teacher and a converter, character traits that Thomas Connolly argues extend back to the Medieval formation of Cecilia’s cult. Connolly demonstrates a strong connection—possibly even a conflation—between the early Christian veneration of Cecilia and the pagan veneration of the Good Goddess, or Bona Dea, a deity known for her ability to heal, and to cure eye disease specifically.[20] Through the conflation of the two subjects, Cecilia could be seen as a saint who healed the figurative blindness of unbelievers. These Medieval associations are similarly present in Benedetti’s libretto, where Cecilia’s role as healer, or giver of sight, is closely tied to her actions as teacher and converter: the blind will see, she promises, once they accept Christianity and obtain faith. Further, the theme of conversion is directly tied to the original title of the oratorio, L’ape industriosa in Santa Cecilia, which may itself be a reference to a single corresponding phrase in the Legenda aurea in which Pope Urban I remarks upon the fruitful results of Cecilia’s proselytizing: “Giesu Christo, Pastor buono, conosco che Cecilia ti serve come fecondissima Ape” (Jesus Christ, Good Shepherd, I know that Cecilia serves you as a productive bee).[21]

2.7 Cecilia’s labors are first exemplified in her conversion of Valeriano, who is initially blind to truth and unable to view the celestial guardian that protects Cecilia’s virginity. In his aria “Se vuoi l’Alma ti ceda,” Valeriano tells Cecilia that his acceptance of her vow of chastity requires proof of the Christian God. [22] Without the knowledge produced by sight, his lust for her will not be tamed. Cecilia, however, insists that Valeriano first abandon his veneration of the pagan gods (recitative: “Se de Numi bugiardi”);[23] only then will he receive the sight that he desires. Yielding to the Christian faith is insufficient, he must open his eyes to the deceits of idolatrous worship.[24] If Valeriano does not acknowledge the error of pagan worship and advance toward Christianity, he will remain blind; faith and action are prerequisites for healing and sight.

| VALERIANO Se voi l’Alma ti ceda, Fà che quel Nume io veda, Per cui ardendo tu, gela il cor mio. Scioglier non può il mortale Quel nodo sì fatale Onde il Ciel in un sen due spirti unio. |

VALERIANO If you want me to yield my soul to you, make it so that I see this God for whom—since you burn for Him—my heart freezes. A mortal cannot untie the fatal knot by which Heaven united two spirits in one breast. |

| CECILIA Se de Numi bugiardi Il Culto detestando, A i raggi della fè non apri i lumi, Li corporei tuoi sguardi In quel Sole Divino, Cieca talpa fissar in van’ presumi. |

CECILIA Unless you open your eyes to the truth of faith, detesting the cult of the lying Gods, in vain do you presume, blind mole, to fix your bodily eyes on that Holy Sun. |

| VALERIANO Già la tua Fede inchino. |

VALERIANO I already yield to your faith. |

| CECILIA E ciò non basta. |

CECILIA And that is not enough. |

| VALERIANO Eccomi pronto, imponi. |

VALERIANO Here I am, ready, direct me. |

2.8 Once Valeriano expresses his readiness to accept Cecilia’s instructions, she directs him to Pope Urban I where he must denounce the pagan idols and confess the truthfulness of the Christian God. In the final lines of her recitative “Se de Numi bugiardi,”and in her succeeding aria, “Spera sì, che dà quell’Onde,”[25] Cecilia delineates the path all souls must follow in their pursuance of cured blindness and restoration of sight: action, faith, and righteous love. Valeriano’s enthusiasm to accept Cecilia’s instructions is indicative of his faith, his movement toward baptism demonstrative of his willingness to act. These two pillars—faith and action—culminate in Valeriano’s righteous love for Cecilia, love in which all carnal lust has dissipated. Through the performance of Valeriano’s conversion, the underlying didactic purpose of the oratorio is achieved: music and education converge in order to instruct the audience what they themselves must do to illuminate the divine beauty of their souls and gain salvation. In this regard, Il martirio di Santa Cecilia is a mixture of earlier and contemporary media technologies. On the one hand, the oratorio draws primarily from Medieval literary renditions of Cecilia’s legend, in which conversion and restorative sight reign supreme; but the delivery of these theological concepts is rooted firmly in the present, relying heavily upon the music to move the affects and draw the heart of the listener to desire comparable spiritual transformation.

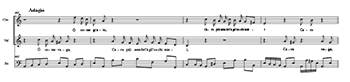

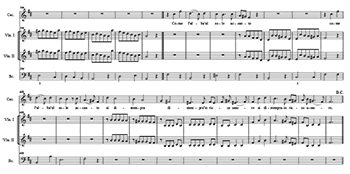

2.9 Colombani represents the sweetness of conversion and clarified sight in Cecilia and Valeriano’s duet “O come vaga o come grato.”[26] Here the spouses’ musical lines alternate fluidly, then join in the perfect harmony of their faithful unity, the peacefulness of which Colombani depicts through an abundance of major and minor thirds. In the beginning of the duet, the thirds appear by way of alternation, where Valeriano’s melody begins on c², and is immediately followed by Cecilia’s reiteration of the tune, now beginning on e² (see Ex. 1).[27] This alternation, representative of the souls as individuals, continues until the two voices join in a string of parallel thirds that represent the unity of the souls in sacred, chaste matrimony, and the clarity with which they now view each other’s beauty (see Ex. 2).[28] Now that each has become an “eternal acquisition” of heaven, their individual beauty and the beauty of their union are reflections of celestial love and goodness.[29]

3. Tiburtio’s Conversion: a Sensory Appeal to Faith

3.1 Overall, the focus on Cecilia’s activities as teacher and converter, and the exclusion of her silent singing, create a parallel with long-established literary traditions such as the Legenda aurea, and seemingly position Cecilia within the established framework of her Medieval saintly identity. Rather than interpreting her legend through a more contemporary lens of early modern mystic devotion, as do the previously discussed iconographic representations, Benedetti uses the libretto to accentuate her pre-established qualities. Cecilia is predominantly a teacher and converter who demonstrates that sight, or understanding, is provided to those who have the faith to act. Colombani supports the contents of Benedetti’s libretto by providing the audience with a musical setting that represents the sweetness and harmony that is given to souls who embrace a higher, rather than earthly, love. In “O come vaga,” his setting is merely a musical reflection of the libretto’s content: the harmony of Colombani’s parallel thirds mirrors the harmony of Valeriano and Cecilia’s congruous souls. The function of the music begins to shift, however, as the audience observes Cecilia’s conversion of Tiburtio. It is within this conversion story that Colombani’s setting begins to take on an exegetical function. Instead of mirroring or emphasizing Benedetti’s story, Colombani uses music to shift the larger message of the oratorio; through his compositional settings, Colombani situates the Medieval foci of the oratorio within a more contemporary context of mystic devotion. The pivotal moment in this thematic alteration is, surprisingly, Cecilia and Valeriano’s performance of “O come vaga,” or rather, the moment in which Tiburtio hears the spouses in duet. The appealing harmonies draw in the unassuming Tiburtio.

3.2 Once Tiburtio hears the duo’s pleasing sonorities, he seeks to discover their origin (“O concenti graditi”).[30] He relishes in the delicacy and grace of the harmonies, but incorrectly identifies the cause of Cecilia and Valeriano’s rejoicing as a celebration of their earthly union. Tiburtio further remarks that a strong scent of lilies and roses is diffused throughout the room, the source of which is unknown to him. This moment of the oratorio references the legend of Cecilia and Valeriano’s celestial coronation, a story included in the Legenda aurea and frequently represented in iconography of the late Renaissance and early modern era (see, for example, Fig. 2, Lelio Orsi’s SS. Cecilia and Valeriano, ca. 1555). In this anecdote Cecilia and Valeriano are visited by an angelic being who crowns the spouses with floral wreaths. To Cecilia and Valeriano, whose faith in Christianity has afforded them perfect sight, the angel and wreaths are fully visible. Tiburtio’s sight, however, remains obscured: although he perceives their sweet aroma, the garlands are concealed from view.

3.3 Scent continues to play a prominent role in Tiburtio’s conversion. Like Valeriano, he desires proof of that which he cannot see. Cecilia again assumes the role of converter as she patiently informs Tiburtio that his inability to see the fragrant wreaths stems from his own blindness: as long as he rejects Christianity, never will his darkened vision see the splendors of the Sun. Valeriano agrees that once Tiburtio’s eyes “catch fire with the beautiful clear light of faith,” Christ will discover him.[31] Once again emphasis is placed upon the key components of conversion: faith and action. The figurative healing of Tiburtio’s blindness will only take place once his internal fire of righteousness is ignited. He must have faith and devote himself to righteous actions. Whereas Cecilia’s command of rhetoric, and more specifically dialectic, is the driving force behind Valeriano’s conversion (the spouses debate the veracity of Cecilia’s love for Valeriano, his faithfulness to her, and his dedication to Christianity over the course of six recitatives and six arias), Tiburtio’s attraction to Christianity is grounded in sensory appeal. More persuasive than religious exhortation is the overwhelming attraction of the heavenly aroma.

3.4 In her aria, “Vago serto di gigli, e di rose,” [32] Cecilia explains to Tiburtio that he is drawn to the garlands’ scent because of their sweetness and celestial origin—the aroma is an invitation to enjoy the pleasures of heaven. Imbedded within her message are references to mystic devotion, namely, the Neoplatonic recognition of scent as an important tool of conversion.[33] These references, however, are purely literary. Through music, Colombani transforms the angelic perfume into a sonic realization of the alluring fragrance, one that also serves as a reference to music’s ability to alter the heart of the listener—first, by delighting the ears, thereby enticing the listener toward conversion, and second, by igniting the affects, stimulating physiological change and moving the listener’s soul toward unity with God or Christ. The heavenly melody of Cecilia’s aria is representative of the music of the spheres, “celestial” harmonies that (as Ficino tells us) spur a realignment of the soul in order to forge a connection between the hearer and divinity.[34] (For more on Ficino’s comments, see Appendix 1.) And so, it is Colombani’s melody that shapes the listener’s interpretation of Benedetti’s libretto. Alone, the text emphasizes the role of scent in Tiburtio’s conversion and by doing so references both the established anecdote and Neoplatonic philosophy. Encased in Colombani’s musical setting, however, the legend’s anecdote and contemporary mystic philosophy are bound to the audience’s auditory senses—docere and delectare converge—and Benedetti’s literary references take on a sensory component: the power of scent is transformed into music’s potent ability to change listeners’ hearts and guide them toward a deeper connection with Christ. As such, the melody is itself a complex tool of mystic devotion: it is sound, it is scent, it is celestial, and it has the power to elevate and change the hearts of those who listen, both anecdotally (Tiburtio) and in reality (the audience).

| CECILIA Vago serto di gigli, e di rose La fronte ne[35] infiora Del Ciel per mercè. E soave, se senti che odora, Con voci odorose T’invita alla fè. |

CECILIA A beautiful garland of lilies and of roses, decorates the brow by the mercy of Heaven. And if it smells sweet to you, with scented sounds it invites you to faith. |

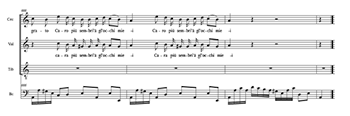

3.5 Colombani sets the celestial melody of “Vago serto” in the key of A major within a series of I–IV–V progressions.[36] The stability of the harmony allows for an active Cecilia, who nimbly lilts across the span of a tenth within the first few measures (see Ex. 3).[37] Her graceful octave and fourth leaps alternate with rising and falling stepwise motion, creating a sonic representation of the fragrance that reflects its diffusion throughout the room; while the aroma wafts around Tiburtio, the melody drifts among the audience. The legerity of the fragrance is similarly present in Colombani’s instrumental setting, which features continuo and a single unison violin line that mirrors the octave leaps and sixteenth-note turns of the voice. Overall, the aria is pleasant and joyful, it is a musical representation of the inviting smells that lead Tiburtio toward conversion and consequent visual clarity. As such, it also serves as an invitation to the audience to move toward Christ, strengthen their faith, and let the music guide them toward perfect sight.

3.6 To Tiburtio, the garlands’ heavenly perfume (and by extension Colombani’s melody) becomes irresistible. He is converted and hastens toward Christianity (“Corro, volo a Giesù”).[38] Now that he has acted, he will be filled with warmth and light; he will gain the ability to see. According to Cecilia, this conversion renders more than restoration of sight. Through his faith and action Tiburtio will be reborn as the phoenix; his transformation through death and toward renewed spiritual life was prompted by the smell of the lilies and roses, represented to the audience as Colombani’s melody. In the oratorio, then, Tiburtio’s spiritual death and rebirth are occasioned by music.

| CECILIA Vola in grembo a Giesù alma felice, Che nel divino ardore Dell’Indiviso benche Trino lume. Arso l’empio costume Risorgerai del Ciel vera Fenice. E tu mio Dio intanto Mi permetti[39] pietoso, Che de trionfi tuoi, io goda il vanto. |

CECILIA Fly into the bosom of Jesus, happy soul, so that in divine warmth of the indivisible, although triune, light, having burned your blasphemous custom, you will be reborn as a true Phoenix of Heaven. And meanwhile, you, my God, full of compassion, allow me to delight in your triumphs. |

4. Music and Mystical Transformation

4.1 The likening of Tiburtio’s religious transformation to his rebirth as a phoenix—an established metaphor for resurrection and continued life after death—is the oratorio’s first reminder to the audience that spiritual death and rebirth are consequences of heartfelt conversion. It is also another example of how the oratorio realigns Cecilia’s Medieval legend within the more contemporaneous framework of early modern mysticism. As Connolly observes, frequent reference to the phoenix is made throughout Cecilia’s Medieval passio, especially in regard to the saint herself.[40] Of particular interest is a passage detailing the conversion of Maximus, a Roman officer who is tasked with confining Valeriano and Tiburtio prior to their final judgments.[41] The brothers persuade Maximus to shelter them in his home; while there, they seek to explain their unwavering devotion to Christianity. During the night, Cecilia arrives and converts all who are in the house. While this section of the passio makes frequent reference to the phoenix, it is within the ensuing passage that Connolly recognizes Cecilia’s own resemblance to the mythical creature:

And so as dawn put an end to night, and a great silence fell, Cecilia spoke: “Hearken, soldiers of Christ! Cast aside the works of darkness and put on the armour of light! You have fought the good fight, you have finished the course, you have kept the faith! Go to the crown of life which God, the just judge, shall give you—and not only you, but all who love his coming!”[42]

4.2 In Connolly’s estimation, the soon-to-be-martyred Cecilia’s “heralding of the approaching day” is a direct reference to the phoenix. For Medieval audiences, the phoenix was a bird that gained new life by experiencing death and was therefore primarily associated with cyclical transformation.[43] The phoenix was a bird of the sun,[44] and in select sources turns to the East and greets its death at dawn.[45] In Lactantius’s De ave phoenice—a source of monumental importance to the cultivation of the phoenix myth among Medieval Christian authors—the phoenix turns toward the rising sun, then “begins to sing a sacred song and to summon the new day with a beautiful sound.”[46]

4.3 Similarities between the phoenix and Christian mysticism are immediately apparent. Most prominently, the phoenix is a bird that awaits, even longs for death, and sees in it the opportunity for continued life. This aspect of its mythology speaks directly to the desires of Christian martyrs to physically die for their faith. But the bird’s physical death is also resemblant to a mystic’s ecstatic or rapturous death, the moment in which God draws the mystic’s soul from their body, and joins it with his spirit in the celestial realm. According to Santa Teresa, this “death” is excruciatingly painful, but it is also overwhelmingly pleasurable, so much so that the soul desires to “die a thousand times” for God.[47] The eroticism inherent in this manner of phrasing was not lost on contemporary readers, regardless of the devotional nature of the phenomenon to which it was applied.[48] Complementary to Teresa’s writings are those of Miguel de Molinos (1628–1696). In his Guida spirituale, Molinos details God’s cleansing and preparation of the soul with whom he wishes to unite in rapture.[49] This occurs through “bitter waters of afflictions, temptations, anguishes, straits, and interior torments,” and through the “burning fire of inflamed, impatient, and ravenous love.”[50] Molinos defines the rapturous death that follows the soul’s preparation as “spiritual martyrdom,” inflicted by God and welcomed by the mystic.[51] After being drawn out of the body, the ecstatic soul is reborn in God, then returned to the body where it may continue the cycle of rapturous death and spiritual life—a cycle that is resemblant to the death and resurrection of Christ, and therefore also the death and renewed life of the phoenix. In addition to this correlation, the phoenix waits for the sun—at times specifically described as the rays or fire that ignite the bird—which, in early modern mysticism, is mirrored in the mystic’s desire for the flames of God’s fiery arrows, arrows that scorch and melt the enraptured soul in the sweet pains of divine love. Finally, there is the phoenix’s song, which calls to mind the power of music to transport the mystic from earth through ecstatic death, and toward renewed life. (For more on Molinos’s Guida spirituale, see Appendix 2.)

4.4 Parallels between the phoenix’s song and early modern mysticism are easily discerned in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century iconographic renditions of Cecilia’s musical rapture. The sonorities of Cecilia’s performance temporarily commingle with the harmonies of the spheres, thereby transporting her soul from the earthly realm and into the realm of divinity where her chastity is guarded, her soul is sustained, and her resolve in Christianity is strengthened. Through her musical performance, she is saved from the severing of her soul from heaven—a necessary consequence of her would-be physical transgression—and instead enjoys a righteous spiritual death, unification with God, and rebirth by way of rapture. As noted previously, however, Colombani’s oratorio begins after Cecilia and Valeriano’s nuptial festivities, and does not mention her ecstatic music or silent singing. Instead, Colombani positions Cecilia’s rapture at the end of the oratorio as the saints prepare for execution, thereby securely aligning her ecstasy with the topoi “death” and “martyrdom.” In doing so, he refashions Cecilia’s Medieval characteristics to be in accordance with early modern iconographic depictions and contemporaneous mystic philosophies: musical rapture, death, and the mythical phoenix coalesce to position Cecilia as an ecstatic (rather than exclusively physical) martyr of the Counter-Reformation.

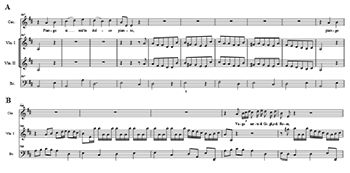

4.5 In Benedetti’s libretto, Cecilia’s desires for physical martyrdom are in vain. Her sentence is postponed while Valeriano and Tiburtio are condemned to death. Cecilia expresses her anguish during her tearful aria “Piango sì, ma in dolce pianto.” [52] In the recitative immediately following (“Così al mio Dio”),[53] Cecilia explains that her tears are an offering, made in honor of Christ’s bloody sacrifice and in place of the physical martyrdom she is denied. Physical death in the name of Christianity, the quintessential sacrifice, remains beyond her reach. As a musical expression of the tears that replace her sacrificial death, Cecilia’s aria “Piango sì, ma in dolce pianto” is the focal point of the oratorio’s mysticism. In the aria, Cecilia proclaims to Valeriano and Tiburtio that although she cries, her tears are sweet and joyful; divine love melts her heart, just as the dawn dissolves at the sight of the sun.

| CECILIA Piango sì, ma in dolce pianto Strugge il cor divino Amore;[54] Come l’Alba al Sole accanto Si distempra in ricco umore. |

CECILIA I cry, yes, but in sweet affliction. Divine love melts my heart; like the Dawn next to the Sun dissolves in rich liquid. |

4.6 Cecilia’s aria does not contain descriptive indicators of rapture found in contemporaneous writings of mystics such as Santa Teresa and Miguel de Molinos: she does not express a longing for death, she does not include dichotomous literary couplings to signal both pain and pleasure, and she does not speak of celestial union. Cecilia does, however, describe her heart as melting (“strugge”), and compares this “sweet” event to the dissolving (“distempra”) of the dawn—words used in mystic literature to describe varying sensations associated with ecstasy.[55] Yet the absence of death—both the literary exclusion of the word from the aria’s text, and Cecilia’s inability to die for Christ—seems to preclude the aria from an ecstatic categorization. I argue, however, that Cecilia’s “Piango sì, ma in dolce pianto” is the epitome of a musical representation of ecstatic death. Cecilia does not describe rapture, nor does she desire it. She experiences it in real time, before the eyes of a watchful audience. Her once private rapture has become public, communal in nature like those of other early modern ecstatics. It is both observed as an embodiment of the iconographic depictions of saintly rapture that surrounded eighteenth-century viewers, and participated in by the audience by way of their visual and auditory senses.

4.7 Critical in discerning Cecilia’s rapture are her tears—the “dissolving” and “melting” of her heart—actualized by divine love, a reference to the tender affection of God or Christ, but also to Divine Love—a Neoplatonic shadow of God.[56] We may, therefore, consider Cecilia’s tears to be an actualization of the emanation of God’s divinity. In other words, her tears are a physical realization of the overwhelming force of Divine Love, the shadow of God, within her heart: God’s love and divinity literally pour from Cecilia’s eyes. Perhaps the most important element of the aria’s text is the metaphor that the melting of Cecilia’s heart resembles the dissipation of the dawn, a sentiment that harkens back to her connection with the phoenix. Like the phoenix, Cecilia too welcomes the sun with singing. In the myth of the phoenix, the rising sun ignites the bird in flames, consuming it and leaving it in ashes. From this, the phoenix emerges reborn. Considering “Piango sì, ma in dolce pianto” in this sense, the aria becomes the phoenix’s song and Cecilia herself the phoenix. Divine Love acts upon her as do the flames upon the bird: it melts and dissolves her heart as it does those of mystic saints, just as fire disintegrates the bird’s physical body. Through her aria, then, Cecilia experiences a metaphorical death and rebirth as the phoenix, akin to that of religious ecstasy. Interpretation of Cecilia’s aria as a musical representation of rapturous death and subsequent rejuvenation is supported by Colombani’s musical accompaniment.

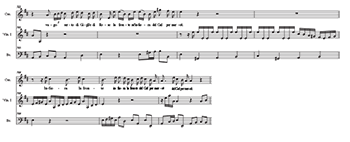

4.8 Colombani sets “Piango sì” in 3/4 time in A major and F-sharp minor, and supports Cecilia’s line with continuo and a series of heartbeat-like eighth notes occurring in unison in the violins. The resulting texture is two voices—Cecilia and accompanying unison violins—above the bass line. Colombani’s texture already creates a breathtaking effect, but most striking is Cecilia’s opening phrase, which is an exact melodic replica of that of “Vago serto” and is similarly composed within a I–IV–V framework (see Exx. 4a and 4b).[57]

Ex. 4b. Colombani, “Vago serto,” mm. 700–4

4.9 Recall that in “Vago serto,” Colombani created for Cecilia a melody that sonically realized the alluring fragrance that drew Tiburtio toward conversion—it was a melody that transformed affects and created a physiological link between the listener and the heavens; it was a melody that had the power to compel the listener toward Christ; it was a melody that elevated the listener. In repurposing the music of “Vago serto” for “Piango sì,” Colombani musically illustrates the moment in which Cecilia experiences her metaphorical death and rebirth by providing her with a melody that has already proven its transformative capabilities. In doing so, he establishes a sonic link between the two arias that signals to the audience the mystic nature of the scene.

4.10 If we consider the enraptured Cecilia in the act of performance, music’s role in her mystic transformation becomes increasingly clear. In the “A” section of the aria Cecilia sings of her tears and of their origination in Divine Love: “Piango sì, ma in dolce pianto / Strugge il cor divino Amore.” Her ecstatic transformation begins in the “B” section, when her death and rebirth are represented in the dissolving of the dawn: “Come l’Alba al Sole accanto / Si distempra in ricco umore.” In other words, Cecilia’s song as the phoenix, in which she welcomes her approaching death or rapture, is initiated in the “A” section, before the true rapture of the “B” section. In Colombani’s oratorio, then, for Cecilia (as it was for Vannini: see par. 1.1 above) music is both a contributor to and consequence of ecstasy. The music of the “A” section, the quoted melody of “Vago serto,” is a key factor in Cecilia’s ascension into ecstasy. Once she is enraptured, the music of the “B” section, though similarly in F-sharp minor, features a melody not found in “Vago serto” (see Ex. 5).[58] This melody is the product of her celestial union with God; it is the melody of Cecilia’s musical rapture.

4.11 Also noteworthy is Colombani’s use of the violin to create an aural relationship between the “A” and “B” sections of “Piango sì.” Not only is the violin featured prominently in the beginning of the aria, where it sets the stage for Cecilia’s ecstatic transformation, its recurring motifs emerge prominently during her moments of rest, effectively creating a sense of dialogue between the vocal and instrumental voices and sustaining the heartbeat-like current throughout the aria. Notable within this dialogue are repeated occurrences in the “A” section of anabasis, during which the violin ascends with sequential triadic figures that intensify the feeling of forward motion and create a sense of drive toward the cadence. This anabasis first occurs in mm. 562–64 of the aria, and is then reiterated in mm. 571–73, where the violin outlines the chords D major–E major–f-sharp minor (supported by root position chords in the continuo: see Ex. 4a).

4.12 The same figure reappears in the violin within the first few measures of the ecstatic “B” section, though here it is condensed (see Ex. 5 above, mm. 604–6). Not only is the violin figure now offset by one beat, occurring after the downbeat rather than as the anacrusis in the previous measure, the sequential pattern is truncated by the omission of the third triad. Additionally, the pattern is no longer pushed forward by the stepwise ascent of the bass line. Instead of driving toward the cadence, the violin’s sequential figure now dissolves into cadential decoration. While a melodic remnant of the anabasis remains intact, the figure itself has disappeared. When the violin rejoins the voice, after the abbreviated recurrence of this motif, it does so without the support of the continuo; it is alone with the rapturous saint, intertwining with the voice in an intimate duet of religious ecstasy.[59]

4.13 After Cecilia’s musically ecstatic death and metaphorical rebirth, and her explanation that her tears must serve in place of physical sacrifice, Valeriano calms her with the reassurance that the rapture she experienced in “Piango sì” is sufficient emulation of Christ’s sacrifice (“Consolati, non piangere”).[60] Physical death, he says, is not a prerequisite for Cecilia’s martyrdom; the languishing of her heart, her desire for death, and her dedication to divine love have already made her a martyr in the eyes of God.

| VALERIANO Consolati, non piangere, Non sospirar più nò. Che l’aspro tuo dolore Già martire[61] d’Amore Al Cielo ti donò. |

VALERIANO Console yourself, don’t cry, yearn no longer; because your biting pain already gave you, a martyr of Love, to heaven. |

4.14 Present in Valeriano’s words is the implication that Cecilia has already achieved martyrdom through rapture. The connection between ecstasy and martyrdom once again references the spiritual death described by Saint Teresa, and more specifically the spiritual martyrdoms of Molinos. Both of these texts claimed a large, lay readership in the late seventeenth and (for Teresa) early eighteenth centuries; and while Molinos had experienced societal ruin almost fifteen years prior to the first performance of Colombani’s oratorio, the internalized devotion, meditative exercises, and veneration of mystic saints promoted by him and other spiritual advisors were firmly rooted in the devotional activities of Colombani’s audiences. We may wonder, then, what Valeriano’s words may have signaled to listeners, particularly those who sought an elevated state of devotion—i.e., transcendence or rapture—that was conventionally exemplified as a saintly phenomenon. Perhaps they too could experience ecstatic, celestial martyrdom through intense longing for Christ and a languishing for death. And, perhaps music could aid them in their mystic journey.

5. Concluding Thoughts

5.1 In this examination of the oratorio’s three protagonists we see a clear adherence to the primary components of Cecilia’s Medieval legend, as well as a refashioning of the saint in accordance with contemporary devotional practices. In Benedetti’s descriptions of Valeriano’s and Tiburtio’s conversions there is continual reiteration of the importance of faith, action, and healing—the keys to righteous veneration. Further, Benedetti’s libretto makes numerous references to the myth of the phoenix, at first directly in description of Tiburtio’s renewed spiritual life (he will be “reborn as a true Phoenix of Heaven”), then indirectly during Cecilia’s rapturous death and rebirth (in the aria “Piango sì”). In both of these approaches there is a strong sense of docere, the primary objective of the oratorio. Benedetti strongly relies on established anecdotes, themes, and metaphors to guide the audience through the most instructive aspects of Cecilia’s legend. The result is a privileging of her identity and priorities that had been promoted since the Middle Ages. Yet his application of the phoenix metaphor—first to Tiburtio and then to Cecilia—presented an opportunity to pivot the reflection of Cecilia’s character toward contemporaneous mystic devotion. Cecilia’s saintly repositioning is aided by Colombani’s musical settings. During Tiburtio’s conversion, scent becomes melody, a virtuous lure toward Christianity (“Vago serto”). Colombani later repurposes this same melody to depict the musical catalyst of Cecilia’s rapture. This melody, which for Tiburtio contained the power for conversion, becomes the impetus behind Cecilia’s ascent into ecstasy. The result is performed rapture, a scene of saintly ecstasy that is brought to life by music. It is a powerful creation of “aural iconography,” in which the sounds of rapture that in literature and iconography are only imagined, envelop the audience and provide multi-sensory access to the most holy of saintly phenomena. Inherent is an eroticized reading of the scene, during which the audience momentarily becomes voyeur, unacknowledged observer of sensuous transcendence as Cecilia performs her climactic ascent into unification with God. The effect is in every way Baroque, for not only does the oratorio teach and delight (docere and delectare), it moves the listeners to engage with the events of the story on a personal level, to allow the music to stimulate their affects (movere) and in doing so deepen their own religious conviction.

5.2 As a final example of the affective power of performances of rapture and the vital role music plays in such depictions, I provide here a quotation extracted from Barbara Russano Hanning’s discussion of representations of Cecilia in seventeenth-century Florence.[62] I invite the reader to imagine in this example Colombani’s Cecilia and her performance of musical ecstasy. Hanning’s quotation is excerpted from Jacopo Cicognini’s dedication of Ottavio Rinuccini’s “sacred verses,” published in Florence in 1619:

But I absolutely must not fail to mention the wonderful amazement that signora Arcangela Paladini Brohomans left in the hearts of everyone there as she represented Saint Cecilia in such a beautiful and devout manner, both with her presence and her song … because she expressed the words and their conceits not only with her truly angelic voice but also with heavenly gestures and movements, sometimes emitting from her upturned eyes the purest rays of humility and devotion, sometimes her face so glowing that it seemed to burn with seraphic love; and, depending on the sense of the song, sometimes her face glistened with a serene and sparkling HOLY JOY (una santa Letizia serena e scintillante), so that with sweet force she imprinted on the heart every affect so vividly that the listeners, stunned, resembled those who have been transported out of themselves.

5.3 Hanning’s example antedates Colombani’s oratorio, but it provides crucial insight from the perspective of an audience member witnessing a musical performance of ecstatic transformation. Primarily, the quotation is exemplary of musical ecstasy as artificial representation—i.e., divine phenomenon becomes religious spectacle. Furthermore, it likely serves as a case of rhetorical hyperbole: signora Arcangela Paladini Brohomans depicts rapture in a way that is so convincing and so enchanting that even her listeners begin to resemble those experiencing mystic elevation. And yet, the passage may indicate an even stronger connection between the viewer and musical rapture. “Rassembravano,” translated by Hanning as “resembled,” was in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries synonymous with “sembrare,” or “to seem.”[63] In this case, Cicognini may have been remarking that the listeners seemed enraptured: not only did they resemble those who are ecstatic, in his estimation they appeared to be so themselves. His word choice may still amount to rhetorical hyperbole,[64] intended to impress upon the reader the captivating power of the performance; but it may also indicate that for some listeners, Brohomans’s artificial representation of saintly joy (una “santa letizia”) —or, saintly rapture—was powerful enough to overwhelm the senses and urge the soul into a state of devotional transcendence.

5.4 Crucial is the single clause “depending on the sense of the song.” In this phrase music’s importance to the representation of celestial rapture is affirmed: the first half of the quotation describes Brohomans’s representation of ecstasy as compelling, and enthralling, but it is the composer who dictates whether the performance of rapture will be transferred onto the listener. We should therefore question the influence Colombani’s transformative melody may have had on audiences, first in “Vago serto” and then in “Piango sì,” especially in consideration of contemporaneous views (articulated explicitly by Valeriano) regarding the accessibility of a martyred union with Christ through rapturous, spiritual death.

5.5 This raises the question of whether performances of saintly rapture, like that in Colombani’s Il martirio di Santa Cecilia, were in fact intended to produce among audience members a shift of affect that could induce celestial rapture. After all, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century descriptions of music as ecstasy or rapture inducing are not uncommon; but as stated previously, I view these descriptions as instances of rhetorical hyperbole, distinct from accounts of musical raptures like those of ecstatics such as Caterina Vannini.[65] Recorded accounts resembling Vannini’s are much less frequent, despite the prevalence of mystic devotional practices and the undoubted connection such practices had to music.[66] This is, perhaps, because of the controversial nature of celestial rapture. In reports documented by and about Church-verified ecstatics, rapture is not an experience that the individual achieves by way of guided meditative exercises or physical preparation (indeed, ecstasy, or rapture, is not even listed by Saint Ignatius as a goal of practiced contemplation); it was an experience that was given to the individual at the behest of God.[67] God alone chose with whom he would unite, regardless of the individual’s engagement in meditation or contemplation. While spiritual exercises were encouraged by certain ecclesiastics, monastics, and lay practitioners, there was an understanding—rooted in theological traditions stemming back to the Middle Ages—that rapture was not arrived at by the soul’s own efforts.[68] Meditative transcendence and rapture were distinct, and while the one could lead to the other, there was no understanding in the early modern mind that the event would occur so sequentially. The selectiveness of the experience, and the lack of necessary aid or guidance by Church authorities (God did not need an authoritative intermediary) made rapture a contested phenomenon, as is evident by the intense ecclesiastic scrutiny placed upon the writings of mystics like Saint Teresa, Saint John of the Cross, and Miguel de Molinos.

5.6 Equally problematic for Church authorities was mystics’ intended readership. Like the oratorio, mystic guides such as Teresa’s Cammino di perfezione and Il castello interiore, and Molinos’s Guida spirituale were written and disseminated in the vernacular, specifically for lay devotees. And so, I return to the question of whether the music in performances of saintly rapture was intended to spur the listener into a meditative transcendence culminating in rapture. I do not believe so. Instead, I propose that performances of rapture were put forth as consequences of idealized model saintliness to which the audience was intended to aspire, but could nevertheless not achieve. By canonizing influential mystics like Teresa and Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi (in 1622 and 1669, respectively), after intense scrutiny of their reported experiences, Church authorities elevated their episodes to events indicative of their saintly status. To be chosen by God for rapturous death was to be marked as the most holy of persons. As individuals who died for God, they became the Counter-Reformation’s ecstatic martyrs. Rapture and designation as a spiritual martyr were reserved for saints. Yet just as saints’ legends were intended as guides and motivation for the improvement of the soul toward hoped-for salvation, so too could the affective music in performances of rapture be influential to individual contemplation and a deepened personal connection with God. Valeriano’s observance that Cecilia’s rapture delivered her soul to heaven as a martyr of love is, therefore, comparable to Cecilia’s instructions concerning the process of conversion. Both illuminate for the listener a path to God. Conversion—detailed by Cecilia and experienced by Valeriano and Tiburtio—was rooted in Cecilia’s Medieval legend, yet still relevant to early eighteenth-century audiences, especially considering the ever-growing strength of Protestant sects beyond Church borders. Rapture—experienced by Cecilia and interpreted by Valeriano—spoke to the devotional milieu that surrounded eighteenth-century audiences on a daily basis.

5.7 Cecilia’s rapture in Colombani’s oratorio may be best understood, then, as a spiritual phenomenon that was simultaneously removed from audiences and made increasingly more available through the act of performance. As a topos repeatedly associated with saints and their longings for martyrdom, ecstatic death was positioned as a spiritual event that was reserved for the holiest of souls, something unattainable for the laity and accessible only vicariously, through the act of listening. In the form of devotional spectacle, the ecstatic phenomenon—once intimate for the individual and unmediated by the Church—became public and controlled. And while the oratorio was first and foremost a devotional genre, the continual use of “death” as a signifier of holy and erotic desire (both in literary and symbolic reference) fostered within it an increasing secularization. Inseparable from these cultural underpinnings was the music, designed to convey the meanings and affects of the libretto, and to intensify the listener’s connection with saints and their desires. At the turn of the eighteenth century, then, the rapturous death depicted in oratorios certainly did serve as a type of aural iconography, where the brilliant representations of ecstatic saints that could be seen throughout sacred and secular spaces came to life, and Counter-Reformation icons died erotic spiritual and physical deaths before the audience’s very eyes.

5.8 Overall, Nicolò Benedetti and Quirino Colombani’s representation of Saint Cecilia in Il martirio di Santa Cecilia elucidates an important function of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Italian oratorios: to rearticulate saints’ established saintly identities and align them within the contemporaneous devotional atmosphere. Oratorios like Benedetti’s and Colombani’s undertook this function by framing traditional aspects of saints’ characteristics within a mystic context. In their rendition of Cecilia’s legend, healing becomes conversion, conversion becomes rebirth, and rebirth becomes reference to the cyclical process of death and rejuvenation by way of celestial rapture. By presenting her in this way, they rebranded Cecilia a saint of musical ecstasy and an ecstatic martyr of the Counter-Reformation. With her identity transformed, she became a figure with whom audience members could forge a connection, like whom they could aspire to become. Cecilia’s physical martyrdom was a sacrifice of the distant past; but her spiritual martyrdom as an ecstatic, identifiable in depictions of her musical rapture in iconography and music, was something much more familiar. Although audience members may never have become one with whom God chose to spiritually unite, though they may never have been able to partake of the sweet pains of ecstatic ascension, musical performances of rapture provided a window into the intimate experiences of mystic saints. Performances of rapture, like that in Colombani’s Il martirio di Santa Cecilia, afforded sensory access to stories of rapture that were previously only known in literature and iconography. Through the act of listening, audiences entered the intimate realm of ecstatic devotion; aural iconography, performed rapture, moved them toward deepened conversion, melted their hearts, and allowed them a taste of overwhelming divine love.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Marc Vanscheeuwijck for extensive discussions and invaluable feedback on the material presented in this article, and for his collaboration on the translation of Nicolò Benedetti’s libretto, L’ape industriosa in Santa Cecilia. I am also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their insights, recommendations, and translation suggestions. Acknowledgement and thanks are also owed to F. Regina Psaki for her detailed review of the translation, and proposed modifications. I would also like to extend my thanks to my mentors/colleagues at the University of Oregon—Margret Gries, Lori Kruckenberg, and Nathalie Hester—for their feedback and performance insights. Special thanks must also be given to the organizers of the UO Musicking Conference, the UO Oratorio Ensemble, and to Susanne Scholz and Dario Luisi for their performance of Quirino Colombani’s Il martirio di Santa Cecilia during the 2019 Musicking Conference.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Ficino on the role of music in the journey of the soul

Appendix 2. A note on Molinos’s Guida spirituale

Examples

Ex. 1. Colombani, “O come vaga o come grato,” mm. 662–65

Ex. 2. Colombani, “O come vaga o come grato,” mm. 666–68

Ex. 3. Colombani, “Vago serto di gigli, e di rose,” mm. 705–711

Ex. 4a. Colombani, “Piango sì,” mm. 567–76

Ex. 4b. Colombani, “Vago serto,” mm. 700–4

Ex. 5. Colombani, “Piango sì,” mm. 601–19 (“B” section)

Figures

Fig. 1. Guido Reni, Santa Cecilia (1606). Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena. www.nortonsimon.org. Courtesy of The Norton Simon Foundation.

Fig. 2. Lelio Orsi, I Santi Cecilia e Valeriano (ca. 1555). Galleria Borghese, Rome. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lelio_Orsi_003.jpg.