The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 28 (2022) No. 1

Girolamo Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali:

Music and Flowery Metaphors in Early Modern Europe

Rebecca Cypess*

Abstract

Girolamo Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali (1635) was one of many volumes of music with floral titles published in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This essay explores these titles and their connections to music, asking what associations they would have called up for early modern composers, performers, purchasers, patrons, and listeners. A sampling of volumes that bear such floral titles reveals some of the aesthetic choices that they imply. Floral titles seem to invite metaphorical thinking linking music with flowers, and the essay explores this approach in the context of early modern European floriculture. The essay concludes by considering the interest in flower gardening among Frescobaldi’s Barberini patrons and suggests that, in the Barberini worldview, flowers were symbols that united the sacred and worldly domains.

2. Floral Titles and Music Books Between Variety and Order

3. In Defense of Flowery Metaphors

4. The Power of Flowers and the Music of Gardens

5. The Barberini and the Meanings of Flowers

6. Reconsidering the Floral Metaphor in Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali

1. Introduction

1.1 The definitive biography of Girolamo Frescobaldi by Frederick Hammond dispatches quickly with the title of Frescobaldi’s magnum opus, the Fiori musicali of 1635: “Titles such as Fiori musicali, Sacri flori, and even Sudori musicali were commonplaces of seventeenth-century music publishing. Nonetheless, Frescobaldi’s Fiori, the last complete collection that he issued, does in fact represent a final flowering in its summary of the genres that he had cultivated throughout his career.”[1] This statement implies that it was the publisher, Alessandro Vincenti in Venice, and not the composer, who settled on the title of the volume, and, in doing so, Vincenti was yielding to commercial interests. Hammond’s concern, by contrast, lies in the volume’s internal contents: its counterpoint, its formal construction, its purely musical qualities. In this respect, Hammond is not alone: the cultural significance of flowers and flower gardens for collections of seventeenth-century music has yet to be adequately explored. Understandably, most discussions of the Fiori musicali are concerned with its remarkable formal and compositional aspects, its performance practices, and its influence on later composers such as Johann Sebastian Bach, who viewed it as a model of contrapuntal writing.[2]

1.2 Frescobaldi’s volume was, of course, not alone in adopting a floral title. The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw the publication of dozens of volumes of music across Europe with titles such as Ghirlanda dei madrigali, Giardino armonico, Le bouquet aux roses, Florilegium, and Celesti fiori musicali, among others.[3] Again, such titles have generally been dismissed as bearing no connection to the music contained in the volumes they adorn. Yet I think this approach may be too hasty. After all, even if it was the publishers of these volumes and not the composers who selected these ornate titles, one must still ask why the publishers thought such titles would appeal to potential purchasers. Why flowers?

1.3 In this essay I will explore these titles and their connections to music, asking what associations they would have called up for early modern composers, performers, purchasers, patrons, and listeners. I first consider a sampling of volumes that bear such floral titles to understand the aesthetic choices that they imply. In my understanding, such titles are not merely “floral” in the sense that they refer to flowers, but “flowery” in the sense that they constitute metaphors that aspire to rhetorical and epistemological flights of fancy. Therefore, I seek to broaden the discussion of volumes with floral titles to explore the kind of metaphorical thinking that they seem to invite. I view these titles in the context of remarkable developments in early modern European floriculture. The sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries saw the rise of a veritable flower mania, sparked by the influx of hundreds or thousands of species of flowers from the New World, the Ottoman Empire, and Asia.[4] With their arrival came a new concern with the classification, study, and collection of flowers, innovative techniques of gardening, notions of the garden as a site of recreation and humanist self-fashioning, and a busy international flower trade. These phenomena were grafted onto such age-old associations as flowers’ medicinal qualities, flowers as Marian and Christian images, and flowers as symbols of womanhood. The layers of meaning embedded in flowers were thus many and rich. Weaving together these different floricultural strains and juxtaposing them with musical composition and practice can offer a new perspective on musical volumes with titles such as Fiori musicali.

1.4 If the floricultural issues to which I have alluded seem far from the field of music, I suggest this apparent ontological gap may result from our modern perspective, which too often views fields of knowledge as separate and distinct from one another. By contrast, early modern writers often embraced the apparent gap between areas of knowledge, linking them metaphorically to generate new ideas and new ways of perceiving the world. Metaphorical thinking was inherent in a Neoplatonist worldview, in which natural and artificial phenomena were understood to be linked through deeply rooted sympathies. As the Neoplatonist perspective made way for—or, more often, merged with—systems of knowledge based on a balance of empiricism and reason, the study of the natural world came to involve extrapolation from one field to the next, with metaphors serving as a springboard for new areas of inquiry. Allowing ourselves to explore and revel in these metaphors may grant us access to a method of learning and discovery that was central to the early modern imagination.[5]

1.5 In fact, Frescobaldi was connected to an active culture of flowers when he published the Fiori musicali. The volume is dedicated to Cardinal Antonio Barberini, whose activities as a cultivator of flowers are richly documented; this documentation suggests that the use of a floral metaphor for Frescobaldi’s volume may have borne a deeper significance than has been recognized up until now. The survival of such evidence attests to the Barberini family’s intense interest in flower gardening and its symbolic meanings, from the humanist to the theological, from the scientific to the mystical. Thus, even within a context in which floral titles were relatively common, Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali stands out as linked to a particularly strong interest in floriculture among the composer’s patrons. This intense interest suggests that the metaphor linking flowers and music—a metaphor proclaimed by the title of the Fiori musicali—would have been one of particular importance for the Barberini.

1.6 In sum, this essay may serve as a thought experiment: if we attempt to orient ourselves in early modern floriculture—and in the metaphorical thinking that the title of the Fiori musicali seems to invite—can we learn something new about this remarkable book of music?

2. Floral Titles and Music Books Between Variety and Order

2.1 Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali has long been recognized for several innovative features, including its overall form, its novel approaches to counterpoint, the great variety of ways in which it treats individual melodies, and the distinctiveness of its toccatas in relation to Frescobaldi’s earlier toccata style. In addition, musicologists have puzzled over the inclusion of the two capriccios based on secular tunes that appear at the end of the volume, with some even calling them “additional” or “extra” pieces—as if they were superfluous—despite their contrapuntal complexity.[6]

2.2 The structure of this collection has been discussed at length in other contexts, but a brief summary is in order here. As shown in Table 1, the bulk of the volume consists of three organ masses—a Messa della Domenica, a Messa degli Apostoli, and a Messa della Madonna—each including a toccata to be played before the Mass, versets for the Kyrie and Christe, a canzona to be played after the Epistle, one or more recercari to be played after the Credo, at least one toccata to be played during the Elevation (in the second mass, a recercar is offer as an alternative to the toccata), and, in the first two masses, a canzona to be played after the Communion. Two capriccios—one based on the Bergamasca and the other on the Girolmeta (Girometta)—close the book.

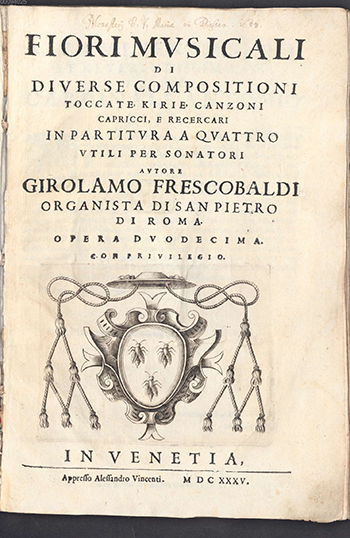

2.3 It is perhaps surprising that the title page of Frescobaldi’s volume (Figure 1) does not signal the book’s inclusion of organ masses at all, instead listing the genres in which the pieces may be categorized: “toccate, Kirie, canzoni, capricci, e recercari.” Even in the table of contents that closes the volume, the division of the collection into three organ Masses plus the two capriccios is obscured by the appearance of all the compositions in a single, undifferentiated list. How can we account for the gap between the relatively organized structure of the Fiori musicali and the obscuring of that structure on the title page and in the table of contents?

2.4 The title Fiori musicali may offer an answer. Although Frescobaldi’s letter of dedication and his note to the reader do little to explain this connection, consideration of other volumes that use similar titles may shed light on the construction of the book. As Christopher Stembridge has already noted, titles with floral imagery are often employed in anthologies; sometimes those anthologies consist of music by a variety of composers, while in other cases they are collections of a variety of compositions by a single composer, often with a printer or other colleague acting as editor.[7] While Frescobaldi’s title page and prefatory material do not make this point clear, the organization of his Fiori musicali can be elucidated through the aesthetics of collecting, curating, and anthologizing. In this respect, it is noteworthy that the word “anthology” itself refers to flower collections, with the Greek ἄνθος (anthos) meaning “flower” and λέγειν (légein) meaning “collection.” This word was translated as florilegium, a title sometimes used in connection with music. The aesthetics of anthologies are thus intimately linked with flowers.

2.5 A handful of examples will illustrate these points. Two volumes titled Celesti fiori that appeared in the years just before Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali—one by Alessandro Grandi (1625) and the other by Horatio Tarditi (1629)—offer some clues as to the implications of floral titles. Both these volumes consist of sacred vocal works, and both indicate that a certain amount of pruning and selection took place to ensure that the volumes would contain the best music possible. The title page of Grandi’s volume indicates that it was not the composer but Lunardo Simonetti, cantor at St. Mark’s, who had chosen the pieces to include in the volume.[8] The letter of dedication in Tarditi’s volume uses the imagery of the garden to explain that he had assembled this book by selecting the best of his own compositions: “I resolved, with animated feelings of devotion, to present to you these, my HEAVENLY FLOWERS, newly collected from the garden of my works.”[9] Yet the title page clarifies that the book was novamente composta, et data in luce (newly composed and published), suggesting that, unlike Grandi, Tarditi had retained control over the selection and assembly of his bouquet.

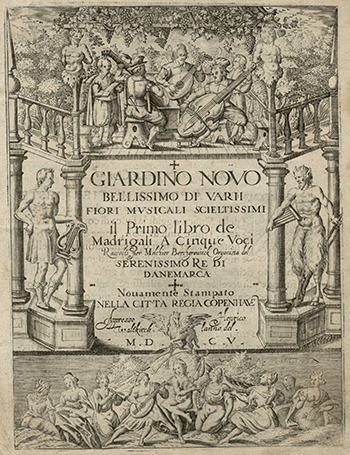

2.6 The theme of collecting is evident, too, in Melchior Borchgrevinck’s 1605 anthology of Italian madrigals, dedicated to King Christian IV of Denmark. This book bears the title Giardino novo bellissimo di varii fiori musicali scieltissimi, with the word scieltissimi (choicest) signifying that the editor had selected the best examples of the genre that he could find. In his letter of dedication Borchgrevinck used floral imagery to refer to the king’s adornment of the arts: “I have dared to pay my debt by planting the heroic name of Your Majesty at the entrance to a small garden, which I have adorned with gracious flowers.”[10] Moreover, the lavish engraving that appears on the cover of Borchgrevinck’s volume (Figure 2) suggests that the music contained in it could be performed outdoors in a garden. At the bottom of the page, classical figures play instruments in an Arcadian landscape; at the top of the page, more realistic characters in seventeenth-century dress play instruments and sing in a garden scene.

2.7 Another madrigal anthology was assembled by the printer Bartolomeo Magni from the oeuvre of Pier’Andrea Ziani: the Fiori musicali raccolti … nel giardino de madrigali à 2. 3. 4. voci del Sig. Pier’Andrea Ziani.[11] In his dedicatory letter, Magni equates his role as editor with that of a flower gardener: “The industrious and discerning gardener collects the most beautiful flowers born in the spring”;[12] similarly, Magni has “assembled a certain quantity of MUSICAL FLOWERS that were made in the green April of the age of S. Pier’Andrea Ziani.”[13] The floral associations of the Ghirlanda di madrigali a sei voci, di diversi eccellentissimi autori de nostri tempi: Raccolta di Giardini di Fiori odoriferi musicali, printed by Pierre Phalèse in Antwerp in 1601,[14] served as a springboard for the Dutch painter N. L. Peschier, who created two vanitas still life paintings incorporating pages from this anthology in 1659–60. In these paintings, pages from Phalèse’s anthology encapsulate both music and flowers in representing the brevity of life, alongside a skull, an hourglass, and other memento mori (Figure 3).[15]

2.8 The year 1632 saw the publication of Johann Hieronymous Kapsberger’s sixth book of villanelle, titled Li fiori.[16] The music in this volume was written while Kapsberger was in the service of the Barberini—a position he had assumed in 1624—so its implications for an understanding of Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali are considerable. The floral title of the book refers primarily to the subject of the texts that Kapsberger set to music. With poetry by Francesco Buti, secretary to Cardinal Antonio Barberini, Li fiori contains a series of songs dedicated to flowers: one song addresses the hyacinth, another the narcissus, another the jasmine, and so on. Kathryn Bosi and Ivano Cavallini have suggested that these songs reflect the contents of the Barberini flower gardens, to which I will turn below.[17] Yet, even in this case, the title also refers to the act of collecting. These pieces were raccolti (collected) by Signore Francesco Tempi, who explained in a dedicatory letter to Kapsberger: “These are the Flowers, poems by Signor Francesco Buti, which you set to music, not without public applause, which flourished in his celebrated academy; and I have been honored … with the task of collecting them.”[18] In fact, Tempi took the act of collecting even farther, interspersing the villanelle about flowers with songs on different subjects: “I do not believe anyone will be displeased to find, between these flowers, canzonets on other subjects; after all, it is not unusual in flower gardens for fruits also artificially to find their place.”[19]

2.9 While Frescobaldi’s volume appears to be the first book consisting entirely of instrumental music published in Italy with a floral title, it seems to have inspired later composers to apply such titles to collections of instrumental music.[20] The letter to the reader in Antonio Croci’s Frutti musicali (1642) pays overt homage to Frescobaldi, suggesting that the practice of Croci’s pieces “will render great benefit” to organists by “making it easier [to play] the compositions of the most illustrious Signor Girolamo Frescobaldi.”[21] The contents of Croci’s book echo the Fiori musicali in their inclusion of organ masses as well as canzonas and ricercars; the title implies that Croci’s music is inspired by Frescobaldi’s and its direct result—the “fruit” borne by Frescobaldi’s flowering plants. And, like other composers of musical gardens, Croci is explicit that the pieces in this book were “made at different times and on different occasions.”[22]

2.10 If these examples of books with floral titles point to the role of the composer or editor as a metaphorical gardener—someone responsible for collecting the best works available and arranging them with an eye to both variety and order—consideration of two contrasting examples helps to clarify the floral aesthetic still further. A first contrasting case is Orazio Vecchi’s Selva di varia ricreatione of 1590. In his preface to this volume, Vecchi explained that he had selected the title “selva,” meaning “forest,” to create a deliberate contrast with gardens:

I say “FOREST,” then, because it does not follow a continuous thread, just as we see the trees in forests placed without the order that we see in artificial gardens.… To this title “FOREST” I then add “of RECREATION,” because just as in a forest one sees that the variety of grasses and plants offers so much delight to the observers, so must the variety of diverse harmonies in these songs of mine resemble a “FOREST.” And I have likewise joined in one the serious style and the familiar, the heavy with the humorous, and with the dance-like, to give rise to the variety that the world so enjoys.[23]

Here, Vecchi proposes a distinction between a musical forest and a musical garden: just as real forests grow naturally, wildly, and randomly, his musical forest is replete with an ever-changing variety. By contrast, in Vecchi’s view, musical gardens are organized and cultivated. This view seems borne out in many volumes whose titles refer to flowers and flower gardens.

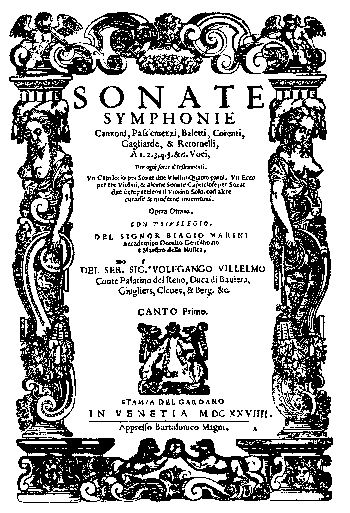

2.11 Books with floral titles are not the only ones that can be fruitfully considered analogous to collections, and this brings us to the second contrasting case. In another context, I have argued that Biagio Marini’s opus 8—the monumental Sonate symphonie, canzoni, pass’emezzi, baletti, corenti, gagliarde, & retornelli—is a musical collection that included curiosities similar to those housed in his patrons’ Kunstkammer. Like the title page of Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali, Marini’s (Figure 4) lists the genres that the book contains, and Marini also specifies some of the more innovative curiosities that the book includes: “un capriccio per sonar due violini quatro parti. Un ecco per tre violini, & alcune sonate capriciose per sonare due è tre parti con il violino solo” (a capriccio in which two violins play four parts, an echo for three violins, and a few capricious sonatas in which the violin plays two or three parts). The one possibly metaphorical aspect of the title is left for last: “con altre curiose e moderne inventioni” (with other curious and modern inventions).[24] Other metaphors are merely implied in the margins: the semi-nude women on the sides of the page point to Marini’s fertile imagination and classical precedents; the cherubs allude to his divine inspiration; the columns place him in the lineage of classical bards, and some of these columns are fused artfully with images of scrolls of the violin, Marini’s instrument. Naturalistic imagery in the form of fruit and leaves, shown at the very top of the page, seems incidental on this busy title page. By contrast, on the title page of Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali, the catalog of genres is relegated to the status of a subtitle, occupying a secondary position in relation to the floral title. Absent is the ornate border that graces Marini’s book—the columns, the women, the cherubs, even the fruit.

2.12 How, then, does Frescobaldi’s volume differ from Marini’s, such that Frescobaldi’s should possess the floral title? Two aspects of Frescobaldi’s book point toward an answer. One is its apparent balance between the variety and order. While Marini’s opus 8 has some pieces grouped together in what appear to be localized structures, his book is so massive in its length and scope that it gives the impression of being all-encompassing.[25] Moreover, Marini’s title page proclaims his interest in “curiosities” and novelties. Frescobaldi’s volume, by contrast, seems more carefully structured and less heavily concerned with musical novelties.[26] While it contains variety in compositional techniques such as contrapuntal devices, it also possesses a logical, internal structure that can be neatly laid out in a table. The works in the Fiori musicali are not simply collected—they are selected, curated, and arranged. Moreover, this helps to explain the apparent gap between the volume’s form—three organ masses plus two capricci—and its obscuring of that form in the title page and the table of contents. The volume is assembled with a view toward variety, but that variety possesses an internal logic.

2.13 While Frescobaldi does not state overtly that his Fiori musicali were anthologized from works created over a long period of time, Stembridge has advanced the theory that this was indeed the genesis of the volume’s contents—that the composer assembled it by selecting the best of his compositions that had not yet been published:

Frescobaldi’s primary concern was perhaps to present the world with a final anthology containing some of his best pieces. In his maturity he had composed a number of outstanding pieces in the various genres which he had developed during his lifetime. The revisions of the instrumental Canzonas found in the 1634 print … show that at this period he was interested in producing compositions of a more concentrated nature; a similar approach is evident in some of the pieces in the Fiori musicali, notably the short toccatas. In the case of some of the other pieces, the lack of a unified approach, including variations in the implied keyboard range, indicates that not all of the music had been newly composed for the volume.[27]

2.14 Additional support for Stembridge’s hypothesis comes from the composer’s use of the floral title, with its attending implications for the assembly of a collection that balances variety and order. Indeed, this notion is amplified by the imagery on the title page of the volume. From 1634, Frescobaldi had enjoyed the sustained support of the brothers Cardinal Antonio Barberini and Cardinal Francesco Barberini. The Fiori musicali is dedicated to Antonio, and the title page features the Barberini family’s insignia, which famously uses the image of bees to represent the family’s virtues. From ancient times to the Renaissance, bees bore such wide-ranging connotations as community, industry, discipline, chastity, monasticism, humanity, wisdom, and reason, sometimes even symbolizing Jesus himself.[28] In the case of the Fiori musicali, however, the bees prompt a metaphorical reading more directly related to flowers: here, the Barberini’s extensive patronage may be understood to have pollinated Frescobaldi’s art, allowing it to flower. And, in keeping with the other volumes with floral titles discussed above, the bees on Frescobaldi’s title page may refer to the composer’s collection of the best examples of his work, analogous to bees’ collection of nectar and pollen from choice flowers.

2.15 This understanding of the imagery on the title page of the Fiori musicali, together with my reading of other volumes with floral titles, suggests that Frescobaldi’s title was more than a mere commercial strategy deployed by the publisher. Rather, I think it reflects a general understanding of the artistic and authorial impulses that shape a musical flower garden—collection and curation, variety and selectivity. Although Frescobaldi does not discuss these aesthetic motivations in his dedication letter or preface, his volume does embrace these impulses as discussed in other volumes with similar titles, and his title page featuring the Barberini bees projects a similar ideal.

3. In Defense of Flowery Metaphors

3.1 The link between floral titles and the assembly of a collection is a metaphorical one: a music book adopts the qualities of a flower garden. Indeed, I think the implications of this metaphor might extend further than I have suggested thus far. The Fiori musicali and other books like it encourage open-ended metaphorical thinking by opening a discursive space between music and floriculture, and this space would have been filled by listeners, performers, patrons, and purchasers of the book in a variety of ways in accordance with the many and multifaceted associations that flowers called up in the early modern imagination. Gaining access to this kind of metaphorical thinking requires us to recalibrate our expectations of historical evidence. It requires a defense of flowery metaphors.

3.2 Early modern European writers in all fields, from the arts to the so-called “hard” sciences, used metaphor extensively as a legitimate methodological tool. As Wendy Beth Hyman has shown, early modern scientists relied heavily on metaphorical thinking to generate new understandings, new knowledge. Hyman cites the linguistic theorist Jeanne Fahnestock, who centers the literary metaphor as a “source of conceptual creativity.”[29] For Hyman, this notion is especially applicable and important in understanding early modern science, leading theorists and practitioners of which maintained a metaphorical approach as a means of creating new disciplines and unearthing new discoveries.

3.3 The suppression of metaphorical thinking in the sciences may be traced to the latter half of the seventeenth century, when members of the Royal Society made a conscious decision to abandon such a method. Thomas Sprat’s History of the Royal Society, first published in 1667, makes this point explicitly by decrying the evils that had been wrought by metaphorical language:

Who can behold, without indignation, how many mists and uncertainties, these specious Tropes and Figures have brought on our Knowledg? How many rewards, which are due to more profitable, and difficult Arts, have been still snatch’d away by the easie vanity of fine speaking? … I dare say; that of all the Studies of men, nothing may be sooner obtain’d, than this vicious abundance of Phrase, this trick of Metaphors, this volubility of Tongue, which makes so great a noise in the World.[30]

By contrast, according to Sprat, the members of the Royal Society

have therefore been most rigorous in putting in execution, the only Remedy, that can be found for this extravagance: and that has been, a constant Resolution, to reject all the amplifications, digressions, and swellings of style: to return back to the primitive purity, and shortness, when men deliver’d so many things, almost in an equal number of words. They have exacted from all their members, a close, naked, natural way of speaking; positive expressions; clear senses; a native easiness: bringing all things as near the Mathematical plainness, as they can: and preferring the language of Artizans, Countrymen, and Merchants, before that, of Wits, or Scholars.[31]

3.4 In fact, Sprat’s fury at rhetorical amplification in scientific thought and writing may be taken as a signal of its persistence. Examples of metaphorical thinking in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries abound. For example, metaphor prompted new experiments with acoustical instruments and the science of sound based on the model of optics. This is clear from the work of figures such as Giovanni Battista Della Porta and Galileo Galilei. When Della Porta attempted to create an ear trumpet to amplify faraway sounds, he made the analogy to catoptric lenses explicit: “In my Opticks I shewed you Spectacles, wherewith one might see very far. Now I will try to make an Instrument, wherewith we may hear many miles.” And, having presented a description of his ear trumpet based on the example of the ears of a hare, he finished by advising the reader: “Fit your instrument to put into your ear, as Spectacles are fitted to the eyes.”[32] Similarly, when Francis Bacon described a method for creating an ear trumpet, he likened it to optical lenses. First advising his readers as to how to make such an instrument, Bacon challenged them to “marke whether any Sound, abroad in the open Aire, will not be heard distinctly, from further distance, than without the Instrument; being (as it were) an Eare-Spectacle.”[33] As Matteo Valleriani explains, Galileo likewise adopted this mechanistic understanding of acoustics and attempted to apply it when, with his one-time student Paolo Aproino, he worked to create his own ear trumpet. However, realizing that he lacked the theoretical understanding of why the ear trumpet worked as effectively as it did, Galileo abandoned the project.[34] The tuba stentoro-phonica or “speaking trumpet” developed by Samuel Morland in 1670 (also claimed by Athanasius Kircher as his original invention) was likewise understood by Morland’s colleagues in the Royal Society as akin to Isaac Newton’s reflecting telescope.[35]

3.5 Thinkers concerned with the field of optics itself likewise drew on metaphor to understand the variability of sight. Paula Findlen has noted that natural philosophers referred repeatedly to the tale of Narcissus to understand the changeability that could be perceived through the study of optics; Ovid’s telling of the myth constituted a metaphorical point of reference. In Findlen’s understanding, “the scientific playfulness of mirrors was a conscious attempt to rewrite the fable of Narcissus, blending ‘poetic fiction’ and scientific fact.”[36] As a whole, Ovid’s fanciful tales of wondrous transformation came to be understood as a representation of nature’s endless variety: as Findlen explains, “It appeared that nature was constantly in flux, always in the process of becoming something else.”[37] Literary metaphor served as an important point of orientation for natural philosophers seeking to keep up with nature’s variability.

3.6 Other fields, too, drew on metaphor as a source of creativity and a prompt to discovery. Paolo Savoia has shown that the technique of surgical grafting emerged from an analogy to botany and horticulture. Savoia explores the treatise on plastic surgery by Gaspare Tagliacozzi, published in 1597, demonstrating that the practice of grafting “moved across disciplines as seemingly unrelated as agronomy and those of medicine.”[38] Likewise, as Lianne Habinek has shown, seventeenth-century studies of neuroscience used metaphors of the architecture of palaces, water works, and mazes to conceptualize the mystery and grandeur of the brain.[39] The workings of the human body could be understood as analogous to musical instruments. Most famously, René Descartes’s Traité de l’homme develops the mechanistic philosophy of human life in relation to mechanical musical instruments.[40]

3.7 The examples offered so far—from optics and acoustics to neuroscience, plastic surgery, and the mechanics of the human body—are just a handful of instances in which metaphor became a driver of early modern scientific thought. In some cases, metaphors between natural philosophy and human artifice worked in both directions. One instance is in the likening of the human body to musical instruments. Just as Descartes understood the human body as analogous to a musical instrument, some musical thinkers understood the mechanics of the human body as a model for understanding musical instruments and their wondrous effects. Thus, writers ranging from the practicing musicians Girolamo Diruta and Michael Praetorius to the poet Giambattista Marino adopted the metaphor of the human body to describe the organ.[41] For Diruta, for example,

The pipes, of whatever material they be, correspond to the throat through which breath passes to form the sound and voice.… Its sound, which reaches the ears like words reflecting the affects of the heart, stands for the interior disposition of the person who plays it. The bellows correspond to the lungs, the pipes to the throat, and the keys to the teeth. Instead of a tongue, the player with light movements of the hand, makes it sound smoothly and almost converse in a good-natured way.”[42]

The notion that this metaphorical trope traversed literary works as disparate as Diruta’s practical organ treatise and Marino’s theological essays, replete with metaphors of all sorts, is itself evidence of the import of metaphor in musical thought. Even if metaphors sometimes served commercial functions—as when a purchaser of a music book is drawn to that book by a floral title—they could still hold deeper significance within early modern arts and letters.

3.8 In fact, I propose that titles such as Fiori musicali constitute an example of a particular type of metaphor—one especially useful in the creation of knowledge. This type of metaphor is catachresis, which Fahnestock defines as a “substitute naming that occurs when a term is borrowed from another semantic field.”[43] Such juxtaposition brings fields of inquiry into proximity and dialogue, encouraging the metaphorical thinking in which countless early modern natural philosophers participated. Still, the question remains: why might Frescobaldi or his publisher, together with the many other composers and publishers who gave floral titles to their music books, have chosen this particular metaphor? Preliminary answers lie, I suggest, in the interest in flowers—an interest that occupied the worlds of natural philosophy, medicine, theology, and commerce—that consumed early modern Europe.

4. The Power of Flowers and the Music of Gardens

4.1 Early modern gardens invited the kind of metaphorical thinking that led to contemplation and the creation of new knowledge. Gardens epitomized the intense interest in exploring and mastering nature, fusing nature and artifice, and pressing all the senses and arts into service of these ends. Gardens presented beholders with the opportunity to explore the paragone (comparison or perceived equivalence) of the senses and the arts and to consider the wonders of nature through application of artifice and technology. That gardens served as a site for the contemplation of metaphor is evident from the association between books and gardens, as discussed above: the anthology was itself a metaphorical flower garden.[44] Jennifer Nevile has shown that European dance choreographies in the Renaissance were often based on and conceived as analogous to the arrangements of gardens.[45] Similarly, the arts of embroidery and lace making came to be understood as outgrowths of flower gardening.[46] Patterns for lacework and embroidery were modeled on the layout of flower gardens, and the templates provided in instruction books or samplers often assume the appearance of floral “knots,” in which flowers of different sorts were planted so that they would intertwine to form intricate patterns. An Italian sampler that makes this connection clear is the Ghirlanda di sei vaghi fiori scielti da più famosi giardini d’Italia, published in 1604, which took its patterns for lace and embroidery from “the most famous gardens of Italy.”[47] Decorative gardening was thus transferred to the domestic, interior space of women’s handiwork.

4.2 In Giambattista Marino’s L’Adone, the garden becomes a site of multisensory exploration: “Pleasure is represented in the figure of the Garden. The five doors symbolize the five senses of the body.”[48] In each area of the Giardino del piacere, Venus and Adonis encounter an enormous array of sensory stimuli, and the gatekeepers of the garden expound at length on the mechanics of the human body in translating these stimuli into affective responses. The sights of flowers, gems, and the dances of the nymphs; the smells of the flowery perfumes and cedar wood; the sounds of birds, which prompt the telling of the story of the nightingale and her infamous competition with a human singer; the taste of the garden’s fruits; and the touch of the beloved—all these contribute to the love story of Venus and Adonis, and they demonstrate the centrality of the garden in thinking about the arts, senses, and human emotions. Music plays a key role in Marino’s garden, and its centrality is only enhanced by its connection to affective and sensual responses to the various other media activated there.

4.3 The erotic imagery in Marino’s description of the garden in L’Adone draws on a long association of flowers with licentiousness and immorality—a factor that led to the censorship of L’Adone by church officials.[49] The garden as a site of women’s temptation was already well established from the biblical story of Eve; yet Eve met her match in Mary, who was often symbolized by flowers or by the hortus conclusus (enclosed garden) of the biblical Song of Songs.[50] The figure of Flora, codified in classical history and mythology and reanimated in the works of early modern poets and artists, is ambiguous. As Elizabeth Hyde has discussed, there were two contrasting origin myths in circulation around Flora—one in which Flora was originally the chaste nymph Chloris, who was raped by Zephyr but “rewarded” with marriage and immortality; and another in which Flora was a notorious prostitute of ancient times. The cyclic nature of flowers—encompassing birth, growth and beauty, withering and death, with ultimate rebirth in the ensuing year—meant that flowers lived between the mortal and the immortal, serving both as a memento mori and as a promise of future life. Thus, in Poussin’s Empire of Flora (Figure 5), the Ovidian figures who morph into flowers are shown at their moments of transformation, with Flora herself spreading her magical immortality.

4.4 The mythology and symbolism surrounding flowers gained a new currency and appeal in the second half of the sixteenth century, growing further in the seventeenth, as countless exotic species of flowers were introduced and proliferated across Europe.[51] As colonial emissaries and Jesuit missionaries encountered new lands and peoples, they sent home samples of floral species, as well as descriptions of their medicinal and decorative properties. Flowers became objects of study, curiosity, and collecting, as natural philosophers such as Ulisse Aldrovandi began to cultivate both private and university gardens for the purpose of learning about horticulture and floriculture.[52] The Accademia dei Lincei, so called because they sought to emulate the keen eye of the lynx, developed new methods for the observation and classification of floral properties, using both topical and internal aspects of flowering plants as means to understand their relationships.[53] The thousands of drawings of flowers and plants that they produced, first commissioned by academy member Cassiano Dal Pozzo, secretary to Francesco Barberini, attest to the Lincei’s fascination with the minute details of the natural world and their role in the creation of the field of botany.

4.5 Even as this scientific inquiry into floriculture arose, faith in flowers as a source of healing—sometimes based on lived experience and sometimes on superstition or the Neoplatonist worldview of sympathetic magic—persisted. In a world so often defined by disease and plague, flowers held the promise of both physical and spiritual healing. Of the many treatises on the healing properties of “simples” (plants, including flowers, thought to possess medicinal properties), John Parkinson’s treatise Paradisi in sole is representative: Parkinson offered to assist women who sought to heal their communities by identifying plants “that are also noursed vp by many in their Gardens, to preserue health, and helpe to cure such small diseases as are often within the compasse of the Gentlewomens skils, who, to helpe their owne family, and their poore neighbours that are farre remote from Physitians and Chirurgions, take much paines both to doe good vnto them, and to plant those herbes that are conducing to their desires.”[54]

4.6 Parkinson lists the “vertues” of many flowers. Violets, for example, could “coole and moisten,” and could be consumed “either fresh and greene, or dryed, and made into powder, especially the flowers.”[55] They were reported to be useful in combatting “the French disease,” but Parkinson notes that this was unproven by experience. “It is not vnknowne, I suppose to any, that Poppie procureth sleepe,” while the “herbe and flowers [of the marigold] are of great vse with vs among other pot-herbes; and the flowers eyther greene or dryed, are often vsed in possets, broths, and drinkes, as a comforter of the heart and spirits, and to expel any malignant or pestilential quality, gathered neere thereunto.”[56] Parkinson waxes rhapsodic and at great length about tulips, and indeed, he was far from alone. The infamous crash of the Dutch tulip market in 1637 should serve as an indicator of how far our own modern floral culture is from the flower mania of early modern Europe. Anne Goldgar has reckoned that, at that time, the cost of a single rare tulip bulb could have bought a small home in Haarlem and been equivalent to three years’ wages of a carpenter in Alkmaar.[57] Exotic types of tulips—alongside many other exotic floral species—attained the status of curiosities to be collected, cultivated, and guarded like the treasures of a Kunstkammer.[58]

4.7 Indeed, even as women (and some men) from the lowest farming class to the patrician housewife continued to cultivate their kitchen gardens and medicinal gardens, the wealthiest and most fashionable members of the aristocracy began to construct what Parkinson calls “gardens of pleasure”—elaborate spaces with flowers, plants, and trees designed in intricate patterns.[59] Such gardens symbolized the power of the aristocratic patron, and they served as vehicles for self-fashioning and sites of recreation, contemplation, and repose. These aristocrats often employed gardeners who were more than mere technicians, but who took on the character of educated gentlemen.[60] In the seventeenth century, treatises by some of the continent’s leading gardeners began to appear; these volumes touched upon everything from the nature and construction of gardening tools, to techniques for enhancing the scent and color of flowers, to methods for making all the flowers in a garden bloom at once, to quasi-mythological allegories and discussions of the virtues of gardens and the patrons who cultivated them.[61]

4.8 Even natural philosophers with wide-ranging interests busied themselves with the study of practical gardening. Francis Bacon, for example, set out a program for “the royal ordering of gardens” by which there could be “gardens for all the months in the year; in which severally things of beauty may be then in season.”[62] Bacon went on to enumerate dozens of species that should be planted to bloom in succession so that “you may have ver perpetuum.” This last phrase, meaning “perpetual spring,” alluded to Virgil’s Georgics, which describes the land of Italy as a vast garden: “Here is continual spring, and summer in unseasonable months.”[63]

4.9 As Marino’s L’Adone suggests, the garden represented the ideal place for consideration of the paragone of the arts and senses. Thus, Bacon continued his essay on gardening by comparing the scent of flowers to the sound of music: “Because the breath of flowers is far sweeter in the air (where it comes and goes like the warbling of music) than in the hand, therefore nothing is more fit for that delight, than to know what be the flowers and plants that do best perfume the air.”[64]

4.10 Indeed, music figured prominently in early modern gardens and floriculture. The engineer Agostino Ramelli proposed a means of arranging flowers indoors and enclosing in them a set of pipes to create the sonic illusion of birdsong. In Ramelli’s illustration (Figure 6), the pipes extend inside a cabinet set against the wall; behind the wall is a person who blows into the pipes. The flower arrangement, animated by sound, thus problematizes the line between nature and art.[65] In the still life by Evaristo Baschenis shown in Figure 7, a theatrical arrangement of musical instruments is supplemented by two items that refer to the garden outside: first are two apples, one seemingly perfect and one with a prominent blemish—perhaps a reference to the fatal fruit eaten by Eve in the Garden of Eden. The second is a book, the title of which appears on its spine: it is the Manuale di giardinieri, the gardener’s manual, written by Agostino Mandirola and first published in 1649.[66] Ornat Lev-er has linked this painting to Baschenis’s own private garden, where he cultivated orange trees and jasmine bushes.[67] This painting suggests that, for Baschenis, who essentially invented the genre of the still life with musical instruments, gardening could serve as an instructive counterpart to the art of music. Instruments of musical artisanship stood alongside instruments of gardening as vehicles to explore and understand both the natural world and humanity’s place in it.

4.11 The villas built in Rome and its environs in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were among the most elaborate in Europe, and their gardens were sites of true multisensory engagement. As David R. Coffin writes, “For the Renaissance Italian, the garden was primarily an outdoor room, where the enjoyment of the colors and fragrances of flowers, the cool shade of trees, and the melodious splash and murmur of water augment the pleasures of dining, social conversation, or amorous dalliance.”[68] Coffin and other historians have emphasized the multimedia nature of the gardens around Roman villas, with music, dance, statuary, and verbal epigrams complementing the cultivated nature contained therein.[69]

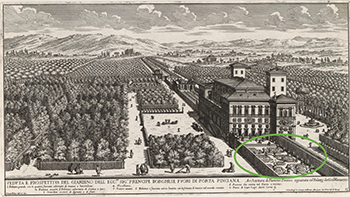

4.12 The Roman gardens were among the first devoted primarily to ornamental design and the recreation (or, to evoke the Garden of Eden once more, the re-creation) of the human spirit. In the gardens surrounding Roman villas, trees covered vast spaces; their organization into blocks, and the decorative layout of each block, can be seen in the view of the Villa Borghese shown in Figure 8. Walkways between the cultivated spaces featured sculptures, many drawn from the remains of classical culture that peppered the city of Rome and the areas around it. Increasingly, these were ordered programmatically to deliver a message—often a moralizing one—to the visitor.[70] Such sculptures were sometimes accompanied by epigrams that the visitor could puzzle out or contemplate during the course of a walk. Fountains—some extremely elaborate, featuring new sculptures to portray classical myths or fantastic scenes from nature—complemented the scene, as did water tricks, which surprised and delighted visitors by soaking them unexpectedly. The most valuable and treasured flowers were contained in the giardino segreto, an enclosed space analogous to the Marian hortus conclusus that was reserved for the owner of the home, his family, and his invited guests. In Figure 8, I have added a circle to show the location of the giardino segreto. As can be seen there, the plants and flowers in this area were arranged in highly organized patterns, though not identical to one another. The flowers in these organized beds would have been planted to create intricate patterns of color when in bloom.

4.13 In elite gardens, music, alongside sculpture and engineering, served as an essential complement to nature; nowhere was this truer than in the villa gardens of Italy. Travelers such as Michel de Montaigne and John Evelyn remarked on the extensive statuary, waterworks, and music that they encountered. Montaigne describes the music he heard at the Villa d’Este, Tivoli:

The music of the organ, which is real music and a natural organ, though always playing the same thing, is effected by means of the water, which falls with great violence into a round arched cave and agitates the air that is in there and forces it, in order to get out, to go through the pipes of the organ and supply it with wind. Another stream of water, driving a wheel with certain teeth on it, causes the organ keyboard to be struck in a certain order; so you hear an imitation of the sound of trumpets. In another place you hear the song of birds, which are little bronze flutes that you see at regals; they give a sound like those little earthenware pots full of water that little children blow into by the spout, this by an artifice like that of an organ; and then by other springs they set in motion an owl, which, appearing at the top of the rock, makes this harmony cease instantly, for the birds are frightened by his presence; and then he leaves the place to them again. This goes on alternately as long as you want.[71]

4.14 Likewise, Evelyn commented on the Muses who seemed to play hydraulic organs on the Mount Parnassus at the Pratolino, as well as the hydraulic organs and “all sorts of singing birds, moving and chirping by force of the water” at the Villa Aldobrandini.[72] Drawing on both these experiences and the writings of Athanasius Kircher, Evelyn included hydraulic music in his own plans for the ideal garden, the Elysium Britannicum.[73] Kircher’s plans for echo chambers and automatic organs both drew upon and contributed to Roman garden music. After remaking the organo ad acqua at the Pontifical Quirinal Gardens in 1647–48, Kircher included the plans for the instrument in his magnum opus on music, the Musurgia universalis.[74]

4.15 What types of music would these automatic organs have played? Fortunately, a handful of notated scores survive to shed light on this question, and these have recently been collected and analyzed by Patrizio Barbieri. As Barbieri notes, one important manuscript by the engineer Giovanni Battista Aleotti provides evidence that popular tunes and other such “light” genres served as the basis of much garden music. This is surely to be expected, given that the statuary of gardens was designed to appear rustic, evoking the pastoral Arcadian world or imitating, through marvelous artifice, the wonders of nature. Aleotti provides settings of the popular song “La Girometta”—one of the two secular songs for which Frescobaldi provided contrapuntal settings in the Fiori musicali—attesting that this tune was used for the hydraulic instruments in some Roman gardens.[75]

5. The Barberini and the Meanings of Flowers

5.1 Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali represents an ideal test case to consider the implications of the floral metaphor in early modern music, since the composer’s Barberini patrons situated themselves at the forefront of Roman floriculture. Indeed, extensive evidence survives to document the Barberini’s intense interest in flowers and gardening; this interest engaged associations ranging from the decorative to the scientific to the spiritual. I will propose that the multifaceted, open-ended symbolism of flowers and flower gardens can help to expand our understanding of the Fiori musicali, and, by extension, it opens new pathways to exploration of other volumes of music with floral titles.

5.2 In the 1620s, the learned Jesuit Giovanni Battista Ferrari turned his attention to gardening and was employed as Francesco Barberini’s chief gardener. Ferrari became one of the leading gentlemen-gardeners in Europe, publishing a lengthy treatise on gardening: the Latin De florum cultura (1633), translated into Italian as Flora overo cultura di fiori (1638).[76] The volume discusses all manner of practical issues related to gardening, including the types of tools that a gardener would need and recommending various ways to enhance the elaborate flower gardens that he tended. The scent of bulb flowers could, for example, be enhanced by cutting open the bulb and pouring in perfume; coloration could be varied by pouring in dye.

5.3 Yet Ferrari’s treatise moves beyond the practical. Drawing inspiration from the Barberini bees, he went so far as to invent new myths in the Ovidian style that incorporated the Barberini bees into floricultural lore. One of Ferrari’s stories tells the tale of two sisters: Melissa, who is devoted to the arts including music, and Florilla, who is devoted to flowers. Melissa begins to sing, and her song so moves Florilla that she languishes and is transformed into flowers. Seeing this, Melissa, whose name means “bee,” changes her song to one of mourning, and she turns into a swarm of bees. In Ferrari’s tale, depicted in Figure 9 in an engraving by Pietro da Cortona, music and flowers are complementary and analogous. The garden, where nature and art achieve a true synthesis, becomes a site of transformation—one that, like Marino’s garden, prompts contemplation of the paragone of the senses. Indeed, the symbolism of the Barberini bees may have enhanced the family’s interest in floriculture. When the Accademia degli Lincei sought to curry favor with the Barberini in the 1620s, they drew on this symbolism extensively. In 1625, the Lincei presented Maffeo Barberini, Pope Urban VIII, with an elaborate engraving of bees drawn in minute detail; according to David Freedberg, it represents the first instance of an artwork drawn with the aid of a microscope.[77] Thus the beauties of nature served as an inspiration or justification for its methodical study at the hands of some of the most revolutionary scientists in Europe.

5.4 Documents relating to the flower gardens of Cardinal Antonio Barberini, dedicatee of Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali, are now preserved in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Garden historian Elizabeth Blair MacDougall shows that these relate to the cardinal’s giardino segreto, his private space reserved for contemplation and repose which, as in many gardens, contained his most highly prized flowers. The library holds a detailed manuscript inventory of Antonio’s garden, a manuscript horticultural treatise, and an elaborate florilegium—literally, an anthology, a book of flowers—that includes artful illustrations such as the one shown in Figure 10.[78] The cultivation of these documents attests to their importance to the cardinal. The inventory and the florilegium attest to his desire to preserve evidence of his interest in flowers for posterity. These documents did not survive by accident: they fix, through writing and the visual dimension, the transitory art of flower gardening.

5.5 As we have seen, the transitory nature of flowers meant that they came to be understood as a memento mori; at the same time, their cycle of birth, death, and regeneration each spring meant that they also encompassed symbolism of immortality, and this symbolism drew on flowers’ Marian associations and the spiritual dimension. Music, like flowers, is temporal and fleeting, though it, too, has the capacity for rebirth with each performance. This temporality meant that music and flowers were natural companions, as seen in the many literary references to music in gardens, as well as in the music that was heard in gardens, carefully planned by engineers such as Aleotti and musical inventors like Kircher. So, too, Kapsberger’s Li fiori apparently seeks to capture Cardinal Antonio Barberini’s gardens through the medium of sound (see above, par. 2.8), and those sounds are preserved for posterity in the printed book. Kapsberger’s book also points to the role of commercial publication in cultivating the image of the Barberini as expert and learned gardeners: those purchasers who did not have direct access to the cardinal’s giardino segreto could gain a sense of its wonders by purchasing the songbook and using it as a script for their own music making.

5.6 The many associations that flowers carried—the spiritual, the classical, the scientific, the commercial, the decorative, the artful—rendered them potent symbols that were available for a wide array of metaphorical interpretations. At the outset of this essay, I suggested one level of metaphorical interpretation: Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali should be understood as an “anthology”—a terms that literally denotes a “collection of flowers,” but one that was applied metaphorically in the early modern era to refer to the selection and careful assembly of works from a larger group. Stembridge’s theory that Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali was assembled from pieces that Frescobaldi had composed over a long period of time thus finds additional support from the custom of using such floral titles for anthologies of music. In this sense, the Fiori musicali may be understood as a flower garden.

5.7 My aim in the remainder of this essay is to move beyond this first level of understanding of the floral metaphor, now considering the broader ramifications of metaphorical thinking for the interpretation of the Fiori musicali as a cultural and artistic document. I will propose a handful of admittedly speculative readings that may help to explain some of the anomalous features of the volume: its organization, Frescobaldi’s novel approach in the toccatas, the use of the contrapuntal technique combining the organ with the organist’s voice, the appearance of epigrams, and the inclusion of the two capriccios that close the book. Yet I think these proposed readings of some of the details of Frescobaldi’s book are less significant than consideration of flowers as a larger symbol. The multifaceted, open-ended meanings of flowers that I have explored in this essay prompt an understanding of Frescobaldi’s music that transcends the details of any one specific feature of his book.

6. Reconsidering the Floral Metaphor in Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali

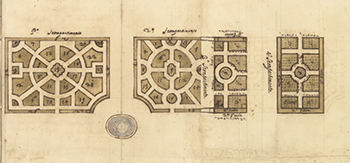

6.1 To begin exploring how we might apply the floral metaphor to the Fiori musicali, I first return to the organization of the volume. We have already seen how this organization seems to straddle the variety that informed early modern collections and the curation and careful assembly that characterized gardens. More specifically, however, I suggest that the organization of Frescobaldi’s volume may be understood as analogous to the compartimenti of a garden. The three organ masses plus the two capriccios based on secular tunes comprise four main sections of the book—three large-scale sections and a fourth, smaller one. While this may be purely coincidental, this four-part organization mirrors the structure of the giardino segreto of Antonio Barberini, documented so richly in the Vatican archive (see Figure 11: image 2 in the linked manuscript). As in flower gardens, the compartimenti are highly structured and similar to one another, but not identical: the scope and details of each are intricately designed to create a sense of variety within the generally unified structure. While Frescobaldi may not have known that Cardinal Antonio’s giardino segreto contained precisely four compartimenti, he would have been familiar with the sectional organization of such private garden spaces and with the dual ideals of variety and detailed organization that they encompass. In effect, Frescobaldi’s book provides a tour of four compartimenti, each displaying its own independent, intricate design.

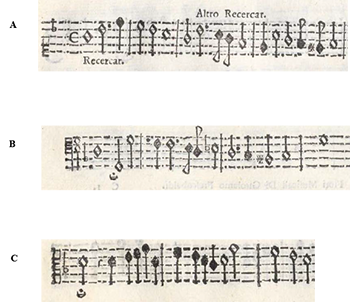

6.2 As in a flower garden, the structure of Frescobaldi’s compartimenti may be appreciated both through a birds-eye view and when experienced in time; in the latter scenario, music, like a garden, offered a path to recreation, re-creation, and healing. The “Altro recercar” of the Messa degli Apostoli offers an example of how this double-understanding plays out in music. In this piece, three subjects appear in three separate sections, as shown in Figures 12a–12c; in the final section (Figure 12d), all three are woven together in an arrangement akin to the embroidery of interlocking flowers. The knotting together of the three subjects exists in two realms: it unfolds in time, in the listener’s or performer’s experience, but, in the last variation, it also stands as a static tapestry to be appreciated through the medium of print and upon reflection after the sounding music has ended. This same double-understanding is evident in the dance choreographies that Jennifer Nevile has shown to be modeled after the construction of gardens. The choreographies unfold through time, but they can also be appreciated in their static form as representations of nature brought under human control.

6.3 The contemplation afforded by the experience of a garden—especially the private, restorative experience of the giardino segreto—resonates with Frescobaldi’s treatment of time in another respect, too. As I have suggested elsewhere, the genre of the toccata in Frescobaldi’s hands requires a negotiation of time in its various early modern conceptions, including both the subjective experience reserved for the individual and the coordinated, regular experience required for organization of the public.[79] This negotiation of competing or complementary ideas of time finds incisive manifestation within the Fiori musicali. Here, the toccatas, shorter than in Frescobaldi’s earlier books, serve as introductions to the Kyries, yet their brevity is matched by the intensity and expansiveness of their realization in the moment; they employ what Alexander Silbiger has called “sustained moods of passionate mysticism.”[80] The suspension of time is key to the experience of both the garden and the toccata, in that both offer the listener moments of repose—of suspended animation—and thus opportunities for spiritual exploration and healing. Scholars such as Gary Tomlinson and, more recently, Remi Chiu, have noted the importance of music in the process of healing illnesses ranging from tarantula bites to the plague.[81] Like healing plants, perhaps, music offered solace and a path to spiritual contemplation; if herbal remedies healed the body, music might heal the soul. Such a notion resonates with the Marian association of flowers in that flowers could represent a physical manifestation of divine benevolence on earth.[82]

6.4 Within the Neoplatonist worldview, remedies involving natural resources such as plants often converged with the Neoplatonist theories that saw music as a healing force. For example, to fight off the plague, Della Porta recommended the use of a lyra made of “no other Wood than the Vine-tree; since Wine and Vinegar are wonderful good against the Pestilence, or else of the Baytree, whose leaves bruised and smelled to, will presently drive away Pestilent contagion.”[83] For Della Porta, music absorbed the essence of the plant to deliver healing. Understood through the spiritual dimension, the garden offered a site of spiritual healing through reflection and consolation, perhaps, again, by invoking the Marian associations of flowers, and this helps to explain why titles such as Fiori musicali occur in sacred volumes such as Frescobaldi’s as well as volumes of, for example, amorous madrigals.

6.5 Within the overall structure of the volume, each organ mass contains its own variations, not only because of the different chants required for different occasions, but also in the seemingly endless variety of contrapuntal methods that the composer adopts. As discussed above, the appreciation of variety in nature and art was a fundamental theme of the early modern collections, including indoor sites like the Kunstkammer or studiolo as well as the cultivated outdoors as manifested in gardens. Gardens such as those of the Barberini juxtaposed the endless variety of nature—newly seen in the influx of exotic flora from other continents—with humanity’s ability to master and control it; this effect was enhanced through the introduction of human arts such as sculpture, waterworks, and music. For Alessandro Tosi, “the garden, like the collection, is an encyclopaedia and a space of knowledge, both metaphorical and real … in which aesthetic and emotional pleasure arises from knowledge.”[84]

6.6 In some respects, the phenomenon of curiosities—unusual or extreme examples of the wonders of nature and art that often figured into collections such as Kunstkammern and studioli—applies to Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali. While most contrapuntal techniques in the volume may not qualify as curiosities, it includes some such rarities. Among these is the “Recercar con obligo di cantare la quinta parte senza tocarla” (Recercar that obliges one to sing the fifth part without playing it) in the Messa della Madonna. These moments of singing are not marked, however. Instead, Frescobaldi presents this performance practice as a puzzle, urging the organist to seek out the solution by using a quotation from Petrarch as an epigram: “Intendomi chi puo che m’intend’io” (Understand me who can, for I understand myself). While Frescobaldi had used this same technique in his Capricci of 1624, its appearance within a volume titled Fiori musicali would prompt the reader, listener, and player to think of it in a new context. One interpretation that might result is that the vocal line is “grafted” onto the instrumental parts as plants or flowers are grafted onto one another. If this analogy appears farfetched, it is worth recalling, as mentioned above, that no less an art than surgical grafting was developed through the application of metaphorical thinking that stemmed from techniques of gardening. In this light, the notion of the garden as a metaphorical framework for understanding this musical technique seems plausible.

6.7 While I think these interpretations of some of the details of Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali are warranted in light of the catachresis effected by the title of the volume, they also seem simultaneously too speculative and too narrow to do justice to the broad, sweeping ideas that flowers called up in the early modern intellectual and scientific imaginations. Here, then, I will turn to a final, metaphorical reading of the Fiori musicali—one that I think is readily justified by aspects of the Barberini’s interest in floriculture but that may also be applied more widely to music books with floral titles. In this reading, the multivalent, open-ended symbolism of flowers is fundamental to contemplation of the divine presence in worldly matters.

6.8 The two capriccios on secular themes that appear at the end of the Fiori musicali serve as a point of entry to this final interpretation. As noted earlier, these pieces have often been regarded as ancillary relative to the rest of the volume, with its overtly sacred agenda. But, as we have seen, the garden was a site where the secular and the sacred converged, and where flowers represented both the divine and the worldly. That the Girometta was suitable for inclusion in a musical garden is clear from the manuscripts of settings of this tune, discussed above, created by the engineer Giovanni Battista Aleotti for the automatic organs in gardens that he designed. However, transplanted to the otherwise sacred context of the Fiori musicali, the Girometta assumes an additional dimension: it breaks down the apparent barrier separating the sacred from the secular, the indoor art of the church from the rustic sounds of the outdoors. The Girometta asks the performer, the listener, and the reader to perceive the beauties of a flower garden in the sacred music of the mass, and to reframe the garden itself as a component of the divine presence on earth. Through contrapuntal complexity and its situation in this predominantly sacred volume, Frescobaldi’s “Capriccio sopra la Girometta” juxtaposes nature and art, the worldly and the holy.

6.9 The epigram that appears at the start of the “Capriccio sopra la Bergamasca” elucidates this point further: “Chi questa Bergamasca sonerà non pocho imparerà” (Who plays this Bergamasca will learn not a little). Epigrams were central to gardens, where they appeared on engraved placards alongside sculptures and fountains, often on classical themes, as a means of inspiring contemplation. Epigrams were also part of the Barberini ethos. Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, who became Pope Urban VIII, was a poet who found meaning in epigrams. The sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini explained how Maffeo used an epigram to understand Bernini’s apparently erotic statue of Apollo and Dafne within a Christian framework:

He made an epigram from the fable of Apollo and Daphne; the story is that Apollo chased Daphne for hours; he was on the point of catching her when she was changed into a laurel bush, the leaves of which he grasped, and in the madness of love put to his lips. The bitterness of their flavor made him exclaim that Daphne was no kinder to him after her transformation than before. This was the substance of the epigram: the joy which we pursue will never be caught or, when caught, will prove bitter to the taste.[85]

6.10 Maffeo’s interpretation of the story of Apollo and Dafne underscores still further the continuity of symbolism enabled by gardens. Like flowers, classical, rustic tales such as this one bore multiple valences and opened themselves to numerous interpretations. The placement of epigrams in gardens allowed for the contemplation of these many meanings. The placement of the “Capriccio sopra la Bergamasca,” together with its epigram, in the Fiori musicali underscores the open-endedness and multiple valences of meaning that it could encompass. The metaphorical garden of the Fiori musicali, like a real flower garden, resists a single interpretation. Instead, it activates a network of associations and meanings, from the sacred to the secular, from the decorative to the scientific, from the commercial to the mystical—a network as complex and intricate as any flower.

6.11 Seen in this light, the two capriccios on rustic songs that close the Fiori musicali are not “extra pieces,” but gestures at the fundamental continuity of the spiritual and the natural. This understanding was encapsulated in a statement by Pirro Ligorio, designer of the Villa d’Este at Tivoli, who reflected on the presence of classical and pastoral themes in the garden that he created:

The good Muses, Clio, Calliope, Erato, Euterpe, Melpomene, Polyhymnia, Terpsichore, Thalia, and Urania. Their mother Mnemosyne, Apollo, Minerva, and Hercules, all these are depicted to signify the labors and happy days of those who are dedicated to higher things, and who lead man to the immortal pleasures of the greatest knowledge, to high and profound meditation on seeing with the eyes of the mind how wonderful is the Prime Mover who made the heavens and the earth, so varied in its concetti. Thus, the force and the essence of the Divine Light can be recognized in plants and animals.[86]

7. Conclusion

7.1 The reading of the Fiori musicali that I have presented offers the possibility of a richer understanding of the cultural and intellectual context that gave rise to this remarkable publication. First, I have suggested that floral titles such as this one refer to the act of collecting, selecting, and arranging. Most often used in connection with anthologies (literally, “collections of flowers”), the floral title appears to refer to Frescobaldi’s own selection and careful arrangement of his music, perhaps lending support to Stembridge’s claim that the works in the Fiori were composed over a long period of time and carefully selected for inclusion in his magnum opus.

7.2 Second, the floral title effects a catachresis that would have prompted metaphorical thinking that linked flowers and music. The implications of this metaphorical thinking are varied and open-ended. Whether for the composer, his patrons, performers, purchasers and users of the book, or others immersed in the musical culture of seventeenth-century Rome, flowers and music had potent connections, and the Fiori musicali opens a dialectic space between them. Making ourselves receptive to the metaphorical thinking implied by Frescobaldi’s title can yield new understandings of the cultural history of this remarkable book.

Acknowledgments

This essay originated as a keynote lecture for the conference “Music and Science During the 1620s,” Luleå University, Piteå, Sweden. I thank Aaron Sunstein and the other conference organizers for providing the opportunity to pursue this project, as well as H. Floris Cohen, Yoel Greenberg, Alexander Silbiger, and the anonymous reviewers for this journal, whose generous comments helped to shape its final form. I am especially indebted to Sally Cypess and Dr. Sandra Messinger Cypess, who helped me develop the initial ideas over games of anagrams during Sukkot 5782.

Figures

Fig. 1. Title page of Girolamo Frescobaldi, Fiori musicali di diverse compositioni (Venice: Vincenti, 1635). Bayerische Staatsbibiothek, Munich, shelfmark 2 Mus.pr. 98. https://stimmbuecher.digitale-sammlungen.de/view?id=bsb00094025.

Fig. 2. Title page of Melchior Borchgrevinck, Giardino novo bellissimo di varii fiori musicali scieltissimi: Il primo libro de madrigali a cinque voci (Copenhagen: Henrico Waltkirch, 1605). Universität Kassel. https://orka.bibliothek.uni-kassel.de/viewer/image/1349423702555/5/LOG_0003/.

Fig. 3. N. L. Peschier, Vanitas Still Life (1659). Oil on canvas, 66.6 cm x 88.8 cm. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O132430/ivanitasi-still-life-oil-painting-peschier-n-l/.

Fig. 4. Title page of Biagio Marini, Sonate, symphonie, canzoni, pass’emezzi, baletti, corenti, gagliarde, & retornelli (Venice: Bartolomeo Magni, [1626]). Biblioteka Uniwersytecka, Wrocław.

Fig. 5. Nicolas Poussin, The Empire of Flora (1631). Oil on canvas, 1810 cm x 1310 cm. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden. The Web Gallery of Art, https://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/p/poussin/2/01flora.html.

Fig. 6. Agostino Ramelli, Le diverse et artificiose machine … nellequali si contengono varij et industriosi movimenti, degni digrandißima speculatione, per cavarne beneficio infinito in ogni sorte d’operatione (Paris: In casa del’autore, 1588), plate 187. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

Fig. 7. Evaristo Baschenis, Still Life with Musical Instruments and Books (seventeenth century). Accademia Carrara, inventory no. 06CB00108. © Fondazione Accademia Carrara, Bergamo. Reproduced by permission.

Fig. 8. View of the Villa Borghese. Giovanni Falda, Li giardini di Roma con le loro piante alzate e vedute in prospettiva (Rome: [Gio. Giacomo de Rossi], [1670]), [p. 32]. The Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/gri_33125008634194/page/n31/mode/2up.

Fig. 9. Pietro da Cortona, The Metamorphosis of Melissa. Giovanni Battista Ferrari, De florum cultura libri IV (Rome Stephanus Paulinus, 1633), p. 519. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/337940.

Fig. 10. Giacinto (hyacinthus orientalis). Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Ms. Barb. Lat. 4326, fol. 34. Thumbnail image: © 2022 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Reproduced by permission of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, with all rights reserved. Overlay image: Elisabeth Blair MacDougall, Fountains, Statues, and Flowers: Studies in Italian Gardens of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Washington, D. C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1993), plate 7.

Fig. 11. Plan of the Barberini giardino segreto. Ms. Barb. Lat. 4265, frontispiece. © 2022 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Reproduced by permission of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, with all rights reserved. https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Barb.lat.4265, [image 2].

Fig. 12. Contrapuntal themes in the “Altro recercar” of the Missa degli Apostoli, in Frescobaldi, Fiori musicali, pp. 53–57: a. first theme; b. second theme; c. third theme; d. the three themes woven together in the final section of the piece. Images from Bayerische Staatsbibiothek, Munich, shelfmark 2 Mus.pr. 98. https://stimmbuecher.digitale-sammlungen.de/view?id=bsb00094025.

Tables

Table 1. Structure of Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali