The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 27 (2021) No. 1

Jeffery T. Kite-Powell – Notating—Accompanying—Conducting:

Intabulation Usage in the Levoča Manuscripts

Appendix. An introduction to NGOT notation[1]

3. An Illustration with Transcription into Modern Notation

1. History

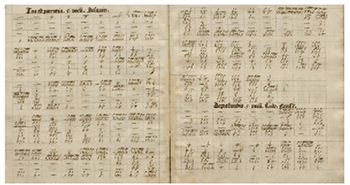

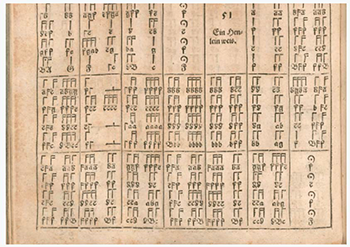

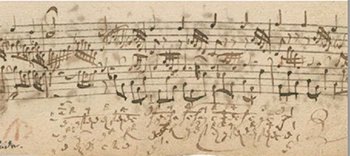

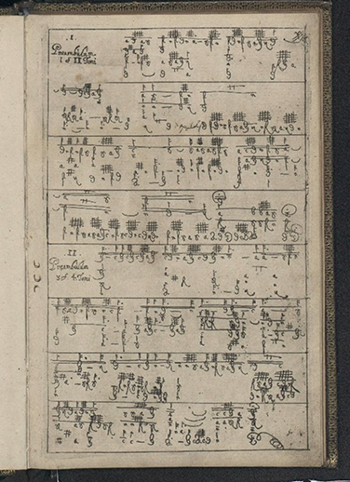

1.1 New German organ tablature (NGOT), often referred to as “keyboard” tablature since harpsichordists also read from this notation, came about as early as around 1520, when German keyboard players modified the style of the older tablature simply by eliminating the staff in favor of an additional row of letters for the uppermost voice. The Klangenfurt MS (1547) is the first complete manuscript to use NGOT (Figure A.1). The first printed example of NGOT was published in 1571 by Nikolaus Ammerbach (Figure A.2). Even J.S. Bach used NGOT several times in his Orgelbüchlein (1708–1717) when he ran out of staff lines, since staves use much more space than letters (Figure A.3). The last known printed example of NGOT is a copper-plate engraving by Johann Erasmus Kindermann from 1645 (Figure A.4). That it was reprinted in 1655 suggests that the compositions contained therein were still of interest, and that organists for at least that decade were able to read NGOT.

2. Characteristics

2.1 Page layout: The keyboardists typically, but not always, read the music across the full width of the open book, instead of down each page in succession; the Kindermann example in Figure A.4 is an exception to the open book approach.

2.2 All pitches are presented with the letters a–h (with b and h representing b-flat and b-natural respectively), and the parts in chordal or polyphonic textures are layered vertically as in a score.[2]

2.3 Rhythmic values are written above each letter or occasionally between two letters, and rests are written within the horizontal row of letters of the voice that is supposed to rest. The notes of the final chord of each composition are provided with a fermata instead of a rhythm sign. A dot affects the note in the same manner as a modern dot, and in some tablatures, ties are employed.[3]

2.4 Bar lines: Periodic use of bar lines can be found in some of the earlier manuscripts, while other manuscripts leave a small space between groups of letters, suggesting some kind of rhythmic grouping of the notes; still others do not give any indication of note groupings or any other organizing characteristic at all. Most of the later manuscripts prefer to separate groupings with spaces, but a few continue the use of the bar line.

2.5 Designation of octaves: Typical for most tablatures, the great octave is indicated by capital letters, the small octave by lower case letters, the one-line octave (cʹ–bʹ) by lower case letters with a horizontal line over them, and the two-line octave (cʺ–bʺ) either by a wavy line over the letters or by two horizontal lines. The octave reaches from c to b in most cases, but variances do occur. Since each letter can indicate only one pitch, clef signs are unnecessary.

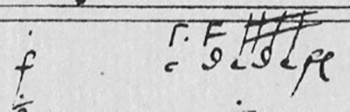

2.6 Chromatic alteration was achieved by attaching a tail-like flourish to the affected letter—usually functioning to raise the pitch—and is valid only for that one letter. This feature precludes possible ambiguities, except in rare cases of scribal carelessness, and eliminates the necessity of key signatures and natural signs. In Figure A.5, the loop on the final note (f-sharp) clearly differentiates that note from the f at the start of the line. In the same way, a loop added to the letter c indicates c-sharp (Cis), while flats were indicated enharmonically by loops added to the letters d and g, resulting in d-sharp (Dis) and g-sharp (Gis), understood as e-flat (Es) and a-flat (As).

2.7 Other points of interest: There are a few instances in which a scribe places the value of a note above the first letter in a series of letters but leaves the space above the remaining letters blank until the note value changes. Rests are placed in the space where a letter (or letters) would normally have been placed, but some scribes are often lax with the placement of rests. In polychoral compositions, rests are generally not inserted for the absent choir.

3. An Illustration with Transcription into Modern Notation

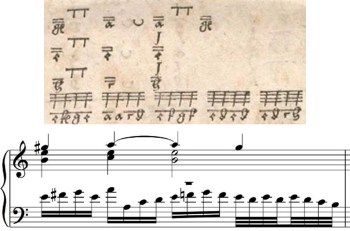

3.1 There are several things to observe in Figure A.6, an excerpt from a piece by Bernard Schmid (1567–1625): the π–like rhythmic symbol above the top row of letters, the tie between the second and third letters, the flourish attached to the first and last letters in the top line indicating the g has been altered to g-sharp, the two short horizontal lines above the letters in the first three rows indicating the two-line octave, the vertical J-like symbol above the third letters of the second and third row of letters showing the rhythmic values of those notes, the single horizontal line above the lowest row of letters indicating the one-line octave, and finally, the first three groups of fence-like patterns in the bottom line indicating groups of sixteenth notes, while the final two groups show thirty-second notes. Note the clash between the g-sharp in the top line and the g-natural in the bottom line (the first beat in the transcription)—a fairly common practice in the day.

Figures

Figure A.1. The Klangenfurt tablature from 1547

Figure A.2. Elias Nikolaus Ammerbach, Orgel oder Instrument Tabulatur (1571)

Figure A.3. J.S. Bach’s usage of NGOT in the Orgelbüchlein

Figure A.4. Johann Kindermann, Harmonia organica (1645)

Figure A.5. NGOT fragment showing f-natural and f-sharp

Figure A.6. Excerpt from Bernard Schmid, Tablatur Buch (1607): facsimile and transcription

References

[1] The content of this Appendix conflates material from Jeffery Kite-Powell, The Visby (Petri) Organ Tablature: Investigation and Critical Edition, Quellen-Kataloge zur Musikgeschichte 14 (Wilhelmshaven: Heinrichshofen, 1979), 37–39, https://www.academia.edu/42217807/; and the Introduction to Kite-Powell, “German Organ Tablature,” in Encyclopedia of Tablature, ed. John Griffiths (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, forthcoming).

[2] A transliteration of the German alphabet typically used in tablatures is given in Kite-Powell, The Visby, 38.

[3] A table showing the rhythmic signs and their equivalents in modern notation is given in Kite-Powell, The Visby, 39.