The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 26 (2020) No. 1

Music in the Thirty Years War:

Towards an Emotional History of Listening

Bettina Varwig*

Abstract

This essay considers music’s contribution to the affective ecology of the Thirty Years War through engaging with recent approaches in the history of the emotions. It proposes that music constituted a unique kind of “emotive” that can offer insights into the corporeal, psychological, and social dimensions of emotional experiences at the time. With reference to some particularly dissonant moments in Heinrich Schütz’s output, I suggest not only that such dissonance could cause listeners actual physical discomfort, but that this discomfort formed a necessary element in the penitential process. This music’s efficacy thus reached beyond the domain of affective representation to offer a powerful form of sonic catharsis.

1. The Thirty Years War: An Affective Ecology

1. The Thirty Years War: An Affective Ecology

1.1 For anyone interested in the history of emotions and their expression in different cultural environments, the Thirty Years War offers an exceptionally rich area of inquiry. There was wide agreement among contemporaries that the war constituted an excess of suffering, fear, and grief, on a scale that had never been known before.[1] The consensus among later commentators, too, has been that the conflict represented, in the words of the historian David Lederer, a “conflagration largely defined by immense suffering,” thereby offering “an optimal test case for the analysis of suffering as an emotional category by historians.”[2] It is certainly worth noting that in much nineteenth- and twentieth-century German historiography, the war and its associated horrors were appropriated as key elements in a problematic broader narrative of national oppression, leading certain present-day historians to question any claims concerning its supposed exceptional status.[3] The statistical evidence, as most recently compiled by Peter Wilson, is nonetheless sobering: whereas the overall casualties in the First and Second World Wars amounted to respectively 5.5 and 6 percent of the European populace, population loss in the Holy Roman Empire during the Thirty Years War came to around 20 percent.[4]

1.2 Such figures tell us little, however, about any actual emotional experiences of suffering in the context of the war, whether individual or collective. Significantly, of the roughly five million people who lost their lives between 1618 and 1648, most did not die as a direct result of combat action, but from the accompanying effects of famine and disease. And the emotional climate of those decades was very much determined by this wider context, which fostered a kind of collective traumatic disposition even among those not immediately involved in military operations. But how can a twenty-first-century historian begin to capture this particular affective disposition? Those working in the history of the emotions have grappled intensely over the past decades with the methodological issues involved in reconstructing the emotional dimensions of historical events.[5] One key problem concerns the relationship between what people of the past may have felt and the terms used to express such feelings, as well as the stability of those terms across larger spans of time. Anyone attempting to write a history of, say, “pain” or “fear” will have to contend with the fact that such categories are culturally determined and historically mutable, with an elusive connection to any felt reality, which ultimately remains impossible to access.[6] Even if one might assume some kind of biological constant underpinning a basic human experience of fear or pain, their modes of expression would have been regulated by the particular emotional scripts operative in a given historical context. Here William Reddy’s notion of “emotives”—as affective utterances that translate an inner feeling into an outward-directed, socially determined gesture—has proven productive in accounting for the cultural work involved in any form of emotional expression.[7]

1.3 Several broad tendencies can be identified that fundamentally shaped these patterns of expression in early seventeenth-century Europe. Various authors have noted a “Baroque propensity to dramatize suffering” in those decades, linked to a conspicuous obsession with death and the Passion of Christ in particular.[8] Closely connected was the widespread expectation that the Last Judgment was imminent, with the apocalyptic temperature rising considerably in the years after 1600. Both Luther’s Reformation and the perceived subsequent increase in natural and human catastrophes were widely regarded as part of an unfolding end-time drama; and it was through this apocalyptic framework that contemporaries could begin to make sense of the exceptional levels of disorder and distress around them. Astrological considerations further intensified the apocalyptic hype, as heavenly portents such as comets and eclipses were routinely interpreted as signs of impending doom. A pamphlet describing a lunar eclipse in October 1631 foretold a whole catalog of disasters, from civil war, uprisings, and the destruction of cities to three-day fevers, fires, shipwrecks, and infectious air.[9] If theologians at the time agreed that the root cause of human suffering and death was original sin,[10] it was God’s wrath about people’s continued sinfulness that was thought responsible for the current depredations visited upon the faithful. A penitential poem of 1631 by the Lutheran pastor Johannes Cörber came to the following conclusion about the ongoing war:

Solch Ubel haben wir verdient

Mit unsern schweren Sünden/

Und weil wir bös gewesen sind/

Hat uns dein Straff thun finden

Man sieht viel Zeichen uberal/

Auff Erden/ und ins Himmelssaal/

Die uns deinn Grimm ankünden.[11](We have earned such misery with our grievous sins, and because we have been wicked, your punishment has found us; there are many signs everywhere on earth and in the heavens that announce your wrath to us.)

Heinrich Schütz, too, subscribed to this view in the dedicatory poem to his Musikalische Exequien of 1636, presenting the current situation as the punishment with which “the Almighty God out of righteous spirit scourged us for our grievous sins and great misdeeds through the fierceness of war.”[12] The collective emotional response to the war thus took shape within an eschatological framework of guilt, repentance, anxious expectation, and longing for salvation.

1.4 What, then, might a consideration of contemporary musical practices contribute to an understanding of this affective ecology? In certain ways, musicians and musicologists have been experts in such questions of emotional “translation” for much longer than the recent research on emotions I just noted, since “moving the affections” constituted the foundational artistic principle for composers and performers across the long seventeenth century. The ways of achieving this emotional communication formed a central topic of discussion among early modern music theorists, whose work was taken up in the early twentieth century by those German scholars postulating a comprehensive “doctrine of the affections” for the Baroque age. Even if this Affektenlehre has lost much of its credibility over the past decades, the consensus still holds, as Barbara Russano Hanning wrote in 2005, that “expressing emotion was at the core of the Baroque aesthetic.”[13] Perhaps surprisingly, then, music has thus far hardly figured on the agenda of leading historians of the emotions. In Jan Plamper’s landmark introduction to the history of the emotions, for instance, music (as well as any other mode of artistic production) goes unmentioned in the section on possible kinds of sources to consult.[14] The omission may be due in part to the persistence—outside of musicology—of a Romantic conception of music as the outflow of a composer’s innermost feelings, which would make musical works only useful for a sort of individual psychohistory. Yet, in Reddy’s terms, music potentially constitutes a uniquely revealing kind of “emotive,” one that not only enacts a (more or less) coherent set of shared affective tropes, but potentially offers insights not afforded by verbal discourse into the mental and bodily operations involved in emotional expression.

1.5 I’m less interested here, then, in contributing to the history of a particular emotion and its fluctuations over time, as much recent historical research on the emotions has done.[15] Instead, I hope to pinpoint some of the ways in which music might serve in the reconstruction of an “emotional history” more broadly, by asking how musical practices at the time reflected and shaped the era’s emotional regimes or “structures of feeling.”[16] As an emotive utterance intended not just to express but to arouse affections, music exerted a tangible force upon performers’ and listeners’ bodies, minds, and souls, thereby urging a holistic understanding of emotion that considers physiology and psychology, sensation and meaning in close conjunction. Traditional musicological approaches have tended to view the process of “moving the affections” predominantly as a matter of representation, in which a particular melodic gesture or harmonic progression might serve to depict a certain textual or affective content. Yet the standard analytical contention that, for instance, a dissonant interval could be used to express “pain” or “grief,” typically assumes a transparent process of translation from felt emotion to verbal category to musical sound and back, when potentially all these operations demand much more nuanced historical interrogation. Using the idea of dissonance as my test case, I propose to investigate here the particular ways in which musical sonorities could be experienced as emotionally charged; that is to say, what exactly was being moved, and how.

2. The Pains of Dissonance

2.1 Any inherited sense of familiarity with seventeenth-century musical patterns of expressing grief, joy, or other emotional states is easily called into question by delving into some of the less frequently cited aspects of contemporary discourse about music’s affective powers. Take this passage from Athanasius Kircher’s Musurgia Universalis of 1650: “If music is meant to move, it requires a listening subject whose natural moisture levels accord with the music.” Or another passage from the same volume: “The time from May to October is much better for making music because of the dry and thin quality of the air.”[17] Kircher is drawing here, of course, on ancient Greek theories of the elements and their properties as well as Galenic humoralism in his conception of the human body. One might argue that the esoteric musings in Latin of a Jesuit philosopher with mystical leanings may not be considered directly relevant to the compositional and listening practices of Schütz’s German Protestant environment. But Kircher’s book was translated into German, and his basic understanding of the physiological and emotive properties of the human body was widely shared among his Protestant contemporaries as well. Here is Andreas Herbst, writing in 1643: “Just as different types of food generate particular kinds of blood flow in the human body, likewise such songs that are embellished with numerous variations of the voices alter, take in, and move the hearts and souls of people.”[18] Or take Wolfgang Silber in his 1615 Encomion Musices, claiming that “the natural spirits of our soul and our blood are so germane and well-disposed to the pleasant melody and sound of music, that a person is easily moved and even enraptured through it.”[19]

2.2 I would suggest that, in order to gain a more grounded historical understanding of the emotional force habitually ascribed to the music of this period, we need to take more seriously the blood- and spirit-based physiology assumed by these writers. Bonnie Gordon, among others, has posited such an approach in relation to certain Italian repertories of the period; and Penelope Gouk has reconstructed aspects of this physiological model with respect to early modern English theories of hearing and the passions.[20] Heinrich Schütz, too, seems to have shared fundamental aspects of such a flow-based conception of human nature, evident for instance in the text for his Klaglied (SWV 501) of 1625.[21] Written as a lament on the untimely death of his wife, Magdalena, on September 6 that year, the piece constitutes an “occasional” and intensely personal utterance; but it also powerfully elucidates some of the broader ways in which music at this time could function as an “emotive,” lending outward expression to a private experience of grief that resonated with wider expectations with regard to that emotion. Its poetry, presumably penned by Schütz himself, echoes some of the physiological parameters set out in Kircher and Herbst:

All mein Freud in bitterm Leid

Ich einsam nun mit stetem Weinen büße;

Das Mark im Gbein mir trocknet ein,

Für Trauren ich kaum fürder setz mein Füße.(In bitter anguish I now atone for all my joy through ceaseless weeping. The marrow in my bones is drying up in me. I can hardly put one foot in front of the other out of grief.)

Tears of sorrow gradually drying out the body’s insides: this is originally a biblical image, but one that had become firmly embedded in early modern flow-based conceptions of human health and emotion. Sigismund Scherertz contended in his 1630 volume on melancholy that “where there is heaviness of heart and sadness of spirit and conscience, we find that the body declines and weakens by the day.” Citing Proverbs 17, he continued: “A sad spirit dries up the bones.… Nothing remains of the person apart from skin and bones, and what is inside them is devoured by sadness.”[22] The same language characterized contemporary descriptions of the mental and physical effects of prolonged warfare. Johannes Cörber reported in 1631: “We hear nothing in all the streets except sighs and groans, the poor people worry, fret, and lament so much that they almost do not seem human anymore; they shrivel like withered leaves, they dry up like shards, they shrink like a sponge, they pale like the dead from all the suffering and heartache.”[23]

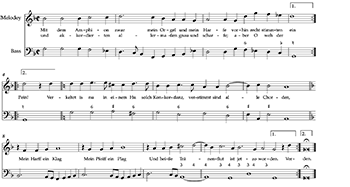

2.3 If early modern music purportedly had the power to move its listeners into or out of such states of sadness or joy, we must assume that this power was grounded broadly in the historical modes of being-in-the-body outlined here. And dissonance had a central role to play in those emotive processes. Schütz’s Klaglied (Example 1) opens with a striking depiction of the effects of grief on musical consonance:

Mit dem Amphion zwar mein Orgel und mein Harfe

Vorhin recht stimmten ein

Und akkordierten allermaßen gnau und scharfe;

Aber o weh der Pein!

Verkehrt ist nu in einem Hu

Solch Konkordanz, verstimmt sind alle Chorden.

Mein Harf ein Klag, mein Pfeif ein Plag,

Und heiße Tränenflut ist jetzo worden.(Although my organ and harp previously accorded well with Amphion, and concorded precisely and acutely in all respects, but oh, the pain! In one instant all such concords are now inverted, all strings are out of tune. My harp has become a lament, my pipe a plague and hot flood of tears.)

Such tropes of reversal formed a common strategy for capturing the extreme experiences of suffering in the wake of the war, most famously perhaps in Andreas Gryphius’s poem “Threnen des Vatterlandes” (Tears of the Fatherland) of 1636:

Wir sindt doch nuhmehr gantz/ ja mehr den gantz verheeret!

Der frechen völcker schaar/ die rasende posaun

Das vom blutt fette schwerdt/ die donnernde Carthaun/

Hatt aller schweiß/ und fleiß/ und vorrath auff gezehret.

Die türme stehn in glutt/ die Kirch ist umbgekehret.[24](So, now we are destroyed; utterly; more than utterly! The gang of shameless peoples, the maddening trumpet, the sword fat with blood, the thundering cannon have consumed our sweat and toil, exhausted our reserves. The towers are on fire, the church is overturned.)

I should note here that Schütz’s Klaglied dates from an early phase of the war, during which his city of residence, Dresden, had remained relatively unaffected; the plague arrived in the city only in 1632, and its suburbs were burnt down by Swedish troops in 1639. But while the piece should therefore most likely not be read as a direct commentary on the warfare raging elsewhere, it still issued from a particular worldview that regarded such “unnatural” phenomena of reversal as contravening divine order. Frequent reports of “monster births” at the time, for instance, upheld a direct connection between such anomalous occurrences and the nearing apocalypse.[25] Schütz’s Klaglied, meanwhile, not only made poetic use of this trope of nature overturned, but translated it into a specific sonic experience, with tangible effects on a listener’s body and spirits.

2.4 In the opening measures, the piece outlines its G-Dorian mode with conventional cadences on the fifth and first degrees, inflected by a number of E-flats in the bass that introduce a Phrygian flavor and draw the piece towards the softer, mollis region of the tonal spectrum. After the repeat sign, a wholesale musical “inversion” of chords is brought about through the introduction of a no-flat key signature, transforming mi into fa, and initiating a drastic sharpward pull via E-natural and C-sharp in the melody, as well as C-sharp, F-sharp, and G-sharp in the accompaniment, to cadence on A. The effect of this aberrant modulation brings to mind Andreas Herbst’s commentary on cadences foreign to the mode, the clausulae peregrinae, which “are used only when the text demands them, as when one wants to indicate something sad, unheard of, horrific, new or abhorrent to nature.”[26] A similar sonic effect of reversal characterizes the remainder of the piece, now back in a one-flat key signature. A consonant upward sequence in the mollis region is followed by a discordant descent on the word “Tränenflut” (Example 1; English translation given above, par. 2.3).

2.5 While these chromatic inflections may strike a present-day listener simply as an overfamiliar ploy of word painting, its effects on contemporary auditors would potentially have been rather more drastic. Here is Herbst again: “Dissonances arise when one puts the sounds or tones together in such a way that by nature they hurt one’s ears.”[27] Or take Kircher, in a characteristically more extreme formulation: “Certain sounds are so incongruous and difficult that one’s teeth grind and ache from them; whereas others are so pleasant and lovely that they want to draw the soul out of itself, so to speak.”[28] Elsewhere, Kircher continued:

If anyone knew the proportion that the sound of an instrument had to the spirits, muscles, and veins of the human body, they would be able to awaken and affect in them whatever they wished. When the sounds are disproportionate, they have an adverse effect on human bodies: because of their vehemence they either injure them or give rise to great pain within them.… Sounds that are too vehement can cause a fright, through which the blood flows together from the outer limbs into the center of the heart.[29]

As a phenomenon that contravened the natural order, dissonant sounds had a material impact on the human ear and body that potentially gave rise to actual physical discomfort. Not unlike diseases or the wrong types of food, such sonic disruptions could instigate a palpable disturbance in the body’s economy of flows. As one war-time medical thesaurus of 1625 noted, “owing to the lack of bread people are often forced to eat unnatural foods in order to still their hunger, from which evil moistures and putrid blood arise in the human body.”[30] Dissonance, too, at least in Kircher’s account, could alter a body’s constitution in ways detrimental to a healthy equilibrium. According to some writers, dissonance even shared with disease and death its origin in original sin. In his Musices Poeticae of 1613, Johannes Nucius noted that prior to the Fall, human nature concorded perfectly with the image of God, but it subsequently fell into a state of deformity as it became infected with the serpent’s venom; owing to this deformity, dissonant sounds now issued from human musical activity, as from “organ pipes that have been mixed up and bent out of shape.”[31] Kircher asserted, too, that humans live in “quotidian discordance,” claiming moreover that illness made the limbs and organs of the body dissonant against each other.[32] The phenomenon of musical dissonance was thus closely connected to both physical health and eschatology in a manner that clearly went beyond the metaphorical—woven into the corporeal fabric of postlapsarian humanity, just as the pain of sin was imagined to break forth, literally, from the spaces between one’s bones. One contemporary medical tract portrayed the often very painful symptoms of gout as follows: “When there is a pain that feels as if one’s bones are being broken, it seems to me that depravity is hiding between those bones and the skin that covers them: where there is a pain, there is evil in the flesh.”[33]

2.6 Such morally charged experiences of physical pain could take on a variety of different shades, often characterized in terms borrowed from other domains of sensory perception. In the same medical handbook, the pains of gout were portrayed as arising from a “sharp, salty moisture” in the body that could cause “sharp and penetrating” or “contracting” or “rough and earthy” spasms of pain, depending on the level of salinity.[34] The pervasive references to categories of taste in the attempt to capture a felt corporeal reality may make us wonder, too, about reassessing some of the standard gustatory tropes for describing the effects of musical sound, as, for instance, when Herbst discussed the Phrygian mode as “by nature angry and sour; it is a martial, heroic, religious, and suffering mode. It is suited to sour and hard words, conflict, mockery, aversion, and so on.” Tellingly, Herbst continues: “In our current times, this mode has become so attractive that it moves people miraculously beyond all measure.… Hence the Phrygian is used especially in prayers, songs of consolation, and funeral songs”[35]—including, not least, in Schütz’s Klaglied, as well as in the Lutheran hymn tune Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu Dir, to which Cörber’s penitential poem cited earlier was meant to be sung. Schütz himself set this tune in his Becker Psalter of 1628 (SWV 235), another compositional venture undertaken in response to the death of his wife.[36] Perhaps, if we are to take Herbst at his word, his harmonization could indeed have made one’s blood run sour, with all the attendant physiological-spiritual ramifications of such a modification of bodily flows.

3. Bodily Penitence

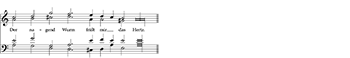

3.1 The Becker Psalter contains a host of other salient examples of this musical physiology at work. In Schütz’s setting of Psalm 38 (SWV 135), the text itself focuses on the corporeal effects of sin, culminating in the image of the worm of evil gnawing on the heart.

Herr, straf mich nicht in Deinem Zorn,

Lass mich dein Grimm verzehren nicht,

Wie scharfe Pfeil und stechend Dorn

Dein Rach verwundt, dein Hand drückt mich,

An meinem Leib ist Gesundes nicht,

All Glied empfinden Leid und Schmerz,

In Mark und Bein hab ich kein Fried,

Der nagend Wurm frisst mir das Herz.(Lord, do not punish me in your anger, do not let your wrath consume me. Like sharp arrows and stinging thorns your vengeance hurts me, your hand presses me. There is nothing healthy in my body, all my limbs feel pain and woe, there is no peace in my bones, the gnawing worm devours my heart.)

This final line of poetry is harmonized in a way that once again effects a striking shift towards the hard or sharp end of the tonal spectrum, with a grating augmented fourth in the inner parts on the word “nagend” (Example 2).

Whether or not the discordant progression would have caused congregants to feel an actual stinging pain in the heart region is impossible to ascertain; but certainly the experience of “heartache” as a symptom of melancholy was widely discussed not simply in metaphorical terms, but taken as literally as a toothache. As Michael Stolberg has explored, the distinctly somatic language of the emotions in this period appears to reflect “their actual experience … as bodily phenomena.”[37] This somatic grounding shaped strategies for rebalancing one’s emotional-physical state as well: a medical thesaurus of 1628 advised that “if the heart-worm torments and stings from fear and gnaws on the heart,” one should get hold of an actual earthworm and tie it to the navel until it dies, in order to draw out the powers of the beast within.[38]

3.2 This direct contiguity between the realms of the physical and the metaphorical, of matter and faith, is evident, too, in the familiar invocation of the “bitter-sweet,” the Petrarchan dolce-amaro, as a sensory-affective category.[39] As Seth Calvisius outlined in his Melopoeia of 1592, dissonances mixed into a consonant harmony had the power to render those concords sweeter and listeners more grateful, “just as light after darkness and sweetness after bitterness causes increased delight.”[40] And once again, there was a deeper theological dimension to these categories of sensory perception. A 1623 devotional volume by the Lutheran pastor Christoph Reymann, which offered “treatments and medicine from the well-stocked pharmacy of the Holy Spirit” to combat the melancholy mood of his time, stated that “our cross is a bitter wood, a sharp biting salt … but the cross of Christ is much more bitter and biting. Yet we cannot make our waters of the cross agreeable unless we pour the bitter wood of his cross into our feeding trough and bring his innocent suffering, his harsh bitter pain, death, and grave into our heart. As soon as we place this wood and this salt into our feeding trough, we will find that there is no better remedy to sweeten our waters of the cross.”[41]

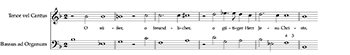

3.3 The spiritual experience of ingesting the bitter waters of Christ’s suffering in order to be released from one’s own earthly travails is arguably encapsulated in musical form in certain intensely bitter-sweet moments in Schütz’s music, such as the opening of the vocal concerto O süßer, o freundlicher (SWV 285) from the first volume of the Kleine geistliche Konzerte (1636): only through the bitter toils of that chromatic “hard passage” (“passus duriusculus” in Christoph Bernhard’s terms) can the sweetness of consonance and of spiritual union with Christ be attained (Example 3.).[42]

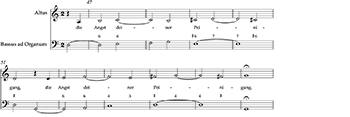

In a traditional text- and representation-based approach, such devices may appear more appropriate for setting more overtly anguished texts such as Was hast Du verwirket, which Schütz included in his subsequent volume of concertos (SWV 307). At the climax of this piece, drawn-out chromatic ascents in the voice accompany the repeated textual phrase “die Angst deiner Peinigung” (“the fear of your torture”) (Example 4a).

But earlier in the piece, too, the tender invocations of “allerholdseligster” (“most blessed”) and “allerfreundlichster” (“most benevolent”) attract similar chromatic progressions in the bass (Example 4b), underlining the emotive agency that music could unfold independently of the specific words it set.

The initial bars of SWV 285, too (Example 3, above), in this way offered an aurally striking and corporeally felt reminder of the central Christian paradox that Christ’s suffering was born of love, that bearing the cross is sweet, that salvation was only attained through due penitence. In the closely analogous opening of another of the Becker Psalter settings, Psalm 84, Wie sehr lieblich und schöne (SWV 181), the same chromatic ascent over a triadic bass accompanies the textual image of Christ’s heavenly abode (Example 5).[43]

Wie sehr lieblich und schöne sind doch die Wohnung dein!

Herr Zebaoth, mit Sehnen verlangt die Seele mein

Den Gottesdienst zu bauen, des Lebens Gott zu schauen,

Mein Leib und Seel sich freun.(How very lovely and amiable are your dwellings! Lord of Hosts, my soul desires with longing to foster devotion, to behold the God of life, my body and soul rejoice.)

Here, too, the music does more than simply mirror the beatific words; it offers layers of affective resonance that would have reverberated through listeners’ bones, blood, and innards. Such passages may not simply have functioned as a sonic representation of the believer’s longing for salvation through Christ, then, but could have viscerally instilled that bitter-sweet sentiment in those singing or listening. What is achieved musically in these chromatically charged progressions, then, is an effective intermingling of various contradictory emotional strands, from the heart-rending realization of one’s own wickedness to anxious anticipation and delirious hope, which is only inadequately captured in any one particular emotion label.

3.4 But why put one’s own body, soul, and spirit voluntarily through this ordeal of being infected with the aberrant sounds of dissonance? By all accounts, the process was not simply gratuitous. If, according to Christoph Bernhard, the ultimate “purpose of composition” was “harmony or euphony,” he still advised that dissonances could be used in such a way that “they become not only inoffensive but actually pleasurable,” and that they could thereby “bring the art of the composer to light.”[44] But for contemporary listeners, the issue clearly reached beyond such artistic or aesthetic concerns. Countless writers at the time confirmed that the most effective remedy for individual heartache as well as the larger catastrophe of the war was heart-felt penitence before God. Thomas Marks has termed this phenomenon “feeling agency,” arguing that expressive gestures such as sighs and tears not only played a role in cultivating true repentance, but that those emotive states could themselves purportedly “enact change” in the material world.[45] And in this respect, dissonance had specific corporeal-spiritual work to do, for this required penitential state had to encompass body, soul, and mind: hardened hearts needed to soften, viscous spirits had to be liquefied, the putrid vapors that clouded the mind had to be expelled. An apocalyptic pamphlet of 1619 urged: “It is high and overly high time to wake up from the sleep of sin … to learn to be shocked by our sins, and to turn to the Almighty with beseeching supplications of our lips and flowing tears of our hearts, which melt our bodies and souls before the angry God, so to speak, as wax melts in the fire.”[46] In this light, the practice of congregational hymn singing, which in some places presumably included some of Schütz’s settings from the Becker Psalter, served not merely as a means of affirming religious doctrine. It constituted a collective bodily-spiritual discipline that aimed to bring about a particular devotional disposition, which may have held the power to avert earthly misery and catastrophe as well as setting the faithful on the path to salvation.

3.5 But if music could aid in the penitential release of tears and anguish, it also helped to rein in their potentially destructive emotional force. In line with Norbert Elias’s classic narrative regarding the increasing regulation of emotional expression as part of an early modern “civilizing process,” members of the higher social classes and men in particular were expected to conform to an emotional regime of restraint in displaying grief and suffering.[47] Moreover, both the medical and theological literature of the time acknowledged that excessive states of sadness and grief only made one’s body more susceptible to infiltration by the plague and other physical or spiritual afflictions. “Our mourning and crying shall nonetheless stay within bounds,” advised Reymann, “for sadness weakens the heart and drains people’s energies.”[48] A 1636 pamphlet about how to avoid catching the plague affirmed that people were more likely to become infected if by nature their bodies were disposed to a detrimental kind of moisture, which gave rise to melancholy— though one should also refrain from fornication, since it weakened the stomach, heart, eyes, and nerves, dried out the body, caused deadly fevers and generally shortened one’s lifespan.[49] Schütz himself agreed that grief needed to be regulated; in the dedication to his Psalm setting Gutes und Barmherzigkeit (SWV 95), written on the death of Jacob Schulte in 1625, he reminded the father of the deceased to “remember that you are a man and, more importantly, a Christian; therefore master your grief with Christian steadfastness.”[50] In this sense the strophic form of the Klaglied potentially served as much to contain and restrain the author’s feelings as to let them flow out of him.

3.6 Incidentally, this strophic arrangement, both in the Klaglied and in the above examples from the Becker Psalter, precluded any close association between melodic gestures and particular words, of the sort often sought out by later analysts. By the final stanza of the Klaglied, the singer has moved on to extolling the joys of heaven, but the music still enacts its opening dissonant reversals. Better, perhaps, to think of the piece as generally redirecting a performer’s or listener’s internal spirits towards a cleansing pattern of flow, not unlike the Aristotelian notion of catharsis in tragic theatre as a process of “purging” or “lightening.” As Kircher affirmed:

Sad people despise and cannot stand music because their spirits or humors are as if frozen and contracted with fear or sadness because of the vivid imagination of evil, so they reject all commotion … but should there be a musician who could dissolve this thickly set spirit with a well-disposed music, they could alleviate their pain and suffering, and dilate the spirits so the sadness passed and a joyful disposition could be reinstated.[51]

In such a scenario, music clearly exceeded the representational function to which artistic expression in this period has customarily been confined in later musicological discourse. Michael Schoenfeldt, for instance, has argued that “a world that had few genuine analgesics at its disposal … would have been more alert to the possible anesthetic effects of literary and artistic representation.”[52] But although Schütz’s Klaglied may in part have arisen out of an escapist impulse, the sonic evocation of pain through dissonance could, more importantly, function as an affective catalyst that created the appropriate kind of disposition for mental and bodily regeneration, until that promised time when no more dissonance was to be heard. Those “wondrously sweet tones and most beautiful melodies” invoked by Schütz in the preface to his Musikalische Exequien foretold of a coming world in which humanity would be liberated from all sin-induced dissonance and would come into harmony with the eternal Alleluias of the afterlife.[53] As Kircher outlined it, in death the believer “is freed from all dissonance of sin and comes into perfect concordance.”[54] Visions of the nearing apocalypse thus not only made sense of contemporary experiences of distress and suffering, but also of the anticipated progress of music from earthly defectiveness to heavenly perfection.

3.7 So did people feel any actual pain in their teeth or between their bones when hearing a dissonant interval or chromatic progression? I hope to have shown here that this is not a facetious question; but ultimately it may still be the wrong question to ask, given the impossibility of recreating the felt reality of any particular historical experience. What seems clear, however, is that these early seventeenth-century encounters with musical sound, and with dissonance in particular, took shape within a wider network of emotionally charged notions about spiritual and actual warfare, about bodies, illness, sin, disaster, apocalypse, morality, and faith, which jointly delineated the historically specific affective environment in which Schütz’s music was created and heard. As one particularly powerful form of emotive utterance, this music could give voice to and transform people’s emotional engagement with the war-torn world around them and the one they so eagerly anticipated.

Examples

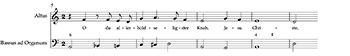

Example 1. Schütz, Klaglied, SWV 501, first strophe

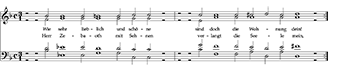

Example 2. Schütz, Herr, straf mich nicht in deinem Zorn, SWV 135

Example 3. Schütz, O süßer, o freundlicher, SWV 285

Example 4a. Schütz, Was hast Du verwirket, SWV 307, mm. 47–56

Example 4b. Was hast Du verwirket, mm. 5–9

Example 5. Schütz, Wie sehr lieblich und schöne, SWV 181