The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2024 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 26 (2020) No. 1

Music and the Leipzig Convention (1631)

Derek Stauff*

Abstract

The Leipzig Convention (spring 1631), convened by the elector of Saxony to address pressing issues of the escalating Thirty Years War, offered Schütz and the Dresden court chapel many opportunities to perform. Wolfram Steude hypothesized that Schütz’s concerto on Psalm 85, Herr, der du bist vormals gnädig gewest (SWV 461), was performed then. This essay questions his argument and proposes instead three settings of Psalm 83 (concertos by Tobias Michael and Samuel Scheidt plus an anonymous motet) that date from this time. Even if not performed specifically at the convention, these pieces are more strongly associated with its politics.

2. Electoral Saxon Politics and the Leipzig Convention

3. Music and Musicians at the Leipzig Convention

4. Schütz’s Concerto on Psalm 85 at Leipzig

5. Psalm 83 and the Leipzig Convention

6. The Hazards of Linking Music to Specific Occasions

1. Introduction

1.1 When the elector of Saxony convened the Leipzig Convention in February 1631, he and his moderate Protestant allies hoped they could prevent the further spread of a conflict already entering its second decade. From across the Holy Roman Empire, the meeting drew Protestants, Lutheran and Calvinist alike, under the aegis of electoral Saxony and Brandenburg. As all Europe looked on, the princes, councilors, and representatives debated and then ratified a neutral Protestant defensive alliance designed to keep the belligerent parties on all sides at bay. Presumably encouraged by the political gravity of the meeting, Johann Georg I of Saxony brought his court musicians and chapel master Heinrich Schütz along to Leipzig, the better to represent his electoral splendor and entertain his guests. The meeting, which lasted from February until April, offered dozens of opportunities for music, sacred and secular, from the Dresden court chapel or Leipzig city musicians. Although Schütz surely performed some of his own music in Leipzig that spring, and perhaps even composed it for the occasion, the historical record has not revealed specific works.

1.2 About twenty years ago, Wolfram Steude hypothesized that Schütz’s concerto on Psalm 85, Herr, der du bist vormals gnädig gewest (SWV 461), was performed at the meeting.[1] This essay will question his argument and its underlying assumption: that we can assign such a piece to a specific event chiefly on the basis of its biblical text. In cases like this, where reliable historical evidence has not surfaced, I argue that the next best solution is to identify pieces written or performed around the time of the event, which seem to resonate with its political aims. To that end, I propose that three settings of Psalm 83 can be more strongly associated with the convention and its politics than Schütz’s Psalm 85. If this still leaves us empty-handed in the search for repertoire definitely heard in Leipzig, the settings of Psalm 83 at least offer examples of a musical response to a major crisis point in the Thirty Years War.

2. Electoral Saxon Politics and the Leipzig Convention

2.1 The political position of the elector and his allies in 1631 helps explain the seriousness of the Leipzig Convention and, by implication, the music performed at or in response to it. The results of the meeting—a confederation of neutral Protestants within the Holy Roman Empire—marked a point of no return in Dresden’s slow drift away from Vienna in the late 1620s and early 1630s.[2] The major points of contention between Emperor Ferdinand II and the Protestant estates were chiefly religious, but they were embedded within major constitutional issues. Chief among these was the emperor’s Edict of Restitution (1629), which stripped Protestants of territory acquired after 1552 and strictly limited religious protections to adherents of the unaltered Augsburg Confession, thus excluding Calvinists. The conflict also took a new turn in 1630 when King Gustavus II Adolphus of Sweden set foot in northern Germany to campaign against encroaching imperial armies. Though Lutheran, the Swedish king did not find eager support among his coreligionists in the Empire, except for those most threatened by the emperor. But as operations expanded inland, pressure mounted on neutral Protestants to commit to one side or the other. To diffuse these tensions and steer them to his benefit, the elector of Saxony convened the meeting in Leipzig with his moderate Protestant allies. His goals were to maintain neutrality, preserve peace in the Empire, and yet hold out the possibility of a Swedish alliance to wrest concessions from the emperor over the Edict of Restitution.

2.2 The Leipzig Convention was really Saxony’s last-ditch attempt to maintain the status quo, a hallmark of Dresden’s imperial politics going back generations. Successive electors, as moderate Lutherans with a prominent seat in the College of Electors, firmly backed the Peace of Augsburg and vigorously, if somewhat blindly, supported the Empire and its institutions.[3] Electoral Saxony’s politics since the reign of Christian II (r. 1591–1611) were also propelled by a vigorous enmity towards Calvinism. When push came to shove, the Saxon electors and their pro-imperial councilors gladly sided with the emperor and the Catholic estates rather than Reformed Protestants.[4] Despite major religious disagreements, Saxony remained conciliatory toward the emperor and his Catholic allies into the 1620s, and this had spared it from the first decade of war and prevented, for the time being, an all-out religious war.

2.3 As the conflict dragged on, Dresden found it increasingly difficult to remain neutral. By the late 1620s, Emperor Ferdinand II had gained the upper hand, using his advantage to swing the balance of power in the Empire fully in the favor of his Catholic allies: he ensured Catholic hegemony in the College of Electors after transferring the title of Elector from a Protestant, the banished Frederick V, Elector Palatine, to Ferdinand’s ally Maximilian of Bavaria; he had ratcheted up the campaign to confiscate property of his defeated enemies, such as the dukes of Mecklenburg, whose territory he then handed to favored allies;[5] and he had pushed forward a more aggressive campaign of recatholicization culminating in the Edict of Restitution in 1629 and the suppression of Lutheranism in Bohemia and in biconfessional Augsburg.

2.4 Lutherans grew frantic. Rumors began to circulate that the emperor, guided by his Jesuit confessor William Lamormaini, would soon rescind the legal privileges that Lutherans had enjoyed since the Peace of Augsburg, putting them on par with Calvinists and other heretics. Fears were stoked by Jesuit writings such as Paul Laymann’s Pacis Compositio (Dillingen, 1629), which argued that even Lutherans no longer followed the unaltered Augsburg Confession and thus violated the terms of the Peace of Augsburg.[6] Johann Georg convened a meeting of theologians in Dresden in 1630 to refute this claim and defend the Augsburg Confession, and the celebration of the centenary of the Augsburg Confession that year must also be understood against this background.[7] Such fears, both real and perceived, drove a wedge between moderate Lutherans and the Catholic emperor.

2.5 At the same time, by late 1630, Johann Georg and his fellow German Protestants also had one eye fixed on north Germany, where King Gustavus II Adolphus of Sweden had recently landed and was trying to gather allies against the emperor and the Catholic League. Sweden’s intrusion into imperial affairs made it an enemy among moderate Protestants, who wanted to maintain the Empire’s constitution. If Gustavus Adolphus were to become too strong, he might coerce neutral Protestants into an alliance. Hence Brandenburg and Saxony looked for a third way between the Imperials and Swedes, a strategy that would finally bear fruit, however short lived, at the Leipzig Convention.

2.6 Johann Georg and his potential allies had debated a neutral and defensive Protestant force within the Empire for more than a year, but the group lacked clear direction and leadership.[8] But by 1630 some of Johann Georg’s advisors showed increasing interest in working with moderate Calvinists. Finally, in late 1630 both Dresden’s privy councilors and its Reformed neighbors pushed for a meeting in Leipzig. The participants arrived in early February, and on the tenth they converged on the St. Thomas Church for the opening service.

2.7 Because so much depended on the decisions made in Leipzig, the meeting drew international attention in the press and in private correspondence;[9] the major European powers eagerly awaited news from Leipzig, and many sent emissaries or secret agents to report on the proceedings.[10] Saxon officials carefully planned events, working with the city to ensure security and to place the proceedings in the most favorable light;[11] the elector instructed that as long as the meeting was in session, all pastors throughout the electorate were to read official prayers drawn up by the Dresden upper consistory.[12] Publishers immediately printed accounts of and documents from the events in pamphlets, broadsheets, and newspapers; and the pro-Imperial press countered with refutations and lampoons.

2.8 The opening service drew special attention because of a sermon on Psalm 83 delivered by Matthias Hoë von Hoënegg. As chief court preacher (Oberhofprediger) to the elector of Saxony, Hoë was by default a leading voice in Orthodox Lutheranism. His sermon was one of the convention’s first published documents, and as it spread rapidly across the Empire, it caused a stir.[13] The sheer number of reprints, from sympathetic and hostile presses alike, attests to its exceptionally broad circulation.[14] Catholics took note. In March 1631, for example, the Swedes passed along to the Saxons an intercepted letter between two Jesuits ending with a remark about the Leipzig Convention: “I sent to Father Gulielmo the sermon, which Herr Hoë preached at the convention at Leipzig. It is nothing other than bluster and enticement to war. He spares no Catholic. They are not a hair better than the worst enemies of God. I do not know with what kind of favor his Imperial Majesty will bear it.”[15] Hoë’s sermon spawned a pamphlet war, and years later he still found himself arguing with his opponents about it.[16] All this shows the weight that contemporaries ascribed to the happenings at Leipzig, including the onlookers at services where elaborate music was heard. Any music performed during or in response to the convention would have resonated against this political backdrop.

3. Music and Musicians at the Leipzig Convention

3.1 Because of the meeting’s seriousness, length, and formality, the elector also brought along his musicians: fifteen trumpeters and drummers plus twenty-four singers and instrumentalists, part of an entourage of over eight hundred.[17] We know their names, including among them Heinrich Schütz’s, thanks to a list uncovered by Wolfram Steude.[18] Schütz’s presence in Leipzig is corroborated by a letter and two albums signed and dated there during the convention.[19] He and the Dresden court chapel members are the only named musicians known to have traveled to the convention. Those from other delegations, apart from trumpeters, have not been documented.[20] Of course, Leipzig musicians were probably active in the city during the convention, especially Georg Engelmann the Elder and Samuel Michael, organists at the St. Thomas and St. Nicholas Churches respectively. At the time of the convention, Leipzig’s top post, city music director, remained vacant after the death of Johann Hermann Schein in November 1630, though Tobias Michael had been appointed Schein’s successor within a month of the latter’s death. But the activities of Michael or other city musicians remain unrecorded in city account books.[21]

3.2 Apart from the names of the Dresden court musicians, we know nothing specific about the music they or the local musicians performed at the convention. The princes gathered in the St. Thomas Church in February 1631 for the opening service did hear concerted music along with Hoë’s sermon on Psalm 83. As usual, contemporary witnesses speak only in generalities, as in this comment from the local chronicler Zacharias Schneider:

They came to the Church of St. Thomas, partly on horse, partly in carriage, and in that place attended the sermon and service, where, besides splendid vocal and instrumental music, Herr Matthias Hoë, Electoral Saxon Chief Court Preacher and Chief Consistorial Councilor, preached a lovely sermon on the eighty-third psalm.[22]

Fortunately, other reports mention a little more about the service, for instance Tobias Heidenreich’s chronicle:

After the sermon, besides other things, a reverent prayer directed at the present undertaking was read out from the chancel and after that concerted music was again made, all of which lasted until after 10 o’clock [in the morning].[23]

The prayer mentioned here may have been the one printed along with Hoë’s sermon.[24] Zacharias Schneider’s unpublished “Annales Lipsienses” adds a few more interesting details: the service was celebrated like an important Sunday or festival day. Psalm 80 substituted for the Epistle, Psalm 83 for the Gospel, confirming a longstanding association between the two texts. The congregation sang two chorales, Wo Gott der Herr nicht bey uns hält and Erhalt uns Herr bey deinem Wort, after which the creed was chanted.[25] Another source mentions drums and trombones during the service.[26]

3.3 Although insufficient to identify composers and specific works at the ceremonies, these details reveal the service’s overarching political and confessional tone, one that likely carried over to the music performed there. Besides the scripture readings and sermon, which foreground the theme of persecution against Protestants, the two chorales, full of anti-papal sentiment, reinforced the gathering’s confessional aims. Erhalt uns Herr shows this clearly with its opening strophe that calls on God to “curb the murderous pope and Turk” (“stewr des Bapst und Türcken Mord”). The other chorale is less specific but just as well suited to the convention, having as its basis Psalm 124, another text connected to persecution.[27] At the St. Thomas Church, the unidentified elaborate vocal and instrumental music stood alongside these texts and most likely added its own confessional significance to the service.[28]

3.4 One factor, however, may suggest that the music heard at the opening service was not newly composed: the service and Hoë’s sermon were not mentioned in records pertaining to the convention until two days before, when the councilors for Saxony and Brandenburg met privately. The minutes describe the meeting where the Saxon councilors work out the ceremonies, presumably involving a proposition to be read, as well as the procedures for the sessions. At the end, their minutes add: “Finally, it was announced to electoral Brandenburg that before [reading] the proposition, a sermon ought to be held here in the St. Thomas Church.”[29] This might indicate that the decision to include the opening service came rather late in the planning, with Saxony’s guests, including Brandenburg, not learning of it until two days before. If Schütz and the elector’s musicians also had only recently found out about the service, they may have had little time to prepare new music.

3.5 Besides the opening, the convention’s closing as well as regular Sunday worship would have offered other chances for elaborate church music. The convention ended with a service on Palm Sunday, April 3, where Hoë again delivered a sermon. The printed sermon itself notes that a concerted Te Deum with trumpets and drums closed the whole gathering.[30] Even after the convention ended, the elector remained in the city and attended numerous services. Again, the reports are vague. The manuscript chronicle of Andreas Höhl reports that the elector attended worship “for the fourth time” on Easter Sunday (April 10), then the following Monday and Tuesday.[31] The regular St. Thomas clergy Polycarp Leyser and Christian Lange delivered sermons then. Hoë, says Höhl, also preached vespers on April 13. Any of these services could have been the occasion for concerted music, perhaps even newly composed for the occasion.

4. Schütz’s Concerto on Psalm 85 at Leipzig

4.1 The only attempt to identify repertoire performed at the Leipzig Convention has come from Wolfram Steude, who proposed Schütz’s concerted setting of Psalm 85, Herr, der du bist vormals gnädig gewest (SWV 461).[32] His main evidence is a large quotation of the psalm at the end of the prayer Hoë gave to close the convention (Psalm 85:7–11, given in bold below; see Appendix 1 for the full psalm):

Vnd du Herr Gott sey vns freundlich/ fördere du das Werck vnserer Hände bey vns/ ja das Werck vnser Hände wollestu allezeit fördern. Ach Herr erzeige vns deine Gnade/ vnd hilff vns/ laß vns hören/ daß du redest/ vnd Friede zusagest deinem Volck vnd deinen Heiligen/ auff daß sie nicht auff eine Thorheit gerathen/ laß deine Hülff vns nahe seyn/ daß in vnsern Landen Ehre wohne/ daß Güte vnd Trewe einander begegnen/ Gerechtigkeit vnd Friede sich küssen/ daß Trewe auff der Erden wachse vnd Gerechtigkeit vom Himmel schawe: thue diß alles aus lauter Gnaden vnd Barmhertzigkeit/ O Herre Gott/ Vater/ Sohn Jesu Christe/ vnd Heiliger Geist/ Du Einiger/ Wahrer/ Hochgelobter/ Hochgebenedeyter Gott/ von Ewigkeit zu Ewigkeit/ Amen/ Amen.[33]

(And you, Lord God, be gracious to us, nurture the work of our hands among us, yea nurture the work of our hands always. Oh Lord, show us your grace, and help us, let us hear that you speak and assure peace to your people and your saints, that they not fall into folly; let your help be near us that in our land glory may live; that kindness and truth meet each other, righteousness and peace kiss, that truth may grow on the earth and righteousness look down from heaven: do all this from sheer grace and mercy, O Lord God, Father, Son Jesus Christ, and Holy Spirit, you only true, highly praised, highly blessed God, forever and ever, Amen, Amen.)

From this passage, Steude concluded:

The extensive quote of Psalm 85 in the closing prayer for the service makes it clear that this text had a central position in the chief court preacher’s field of vision. The probability is very high that at his suggestion Heinrich Schütz composed the psalm “Herr, der du bist vormals gnädig gewest” (SWV 461) either as an Introit for the opening of the convention on 10 February or for the closing service on 2 April 1631. The Dresden court chapel, staying then in Leipzig, as shown, was large enough to be able to perform the substantial work.[34]

4.2 Steude’s argument is questionable. In view of all the scripture quoted in this prayer and in Hoë’s two published sermons for the convention, these five verses from the middle of Psalm 85 did not receive particular emphasis. Hoë’s closing prayer alone also cites Isaiah 11, Proverbs 8, and Psalm 90. (See Appendix 2.) The quotation from Psalm 90 is nearly equal in length to the excerpt from Psalm 85. Moreover, Psalm 85 was common as a reading and as a quotation in prayers and sermons for political occasions during these years. In another sermon delivered a few months after the Leipzig Convention at the meeting of the territorial estates (Landtag) in Dresden, Höe again closed with a lengthy prayer featuring Psalm 85 in nearly its entirety.[35] This quotation far surpasses in weight and scope the one in Hoë’s earlier prayer for the Leipzig Convention. Steude, it turns out, knew this. In an earlier essay, he suggested the 1631 Landtag as a probable occasion for Schütz’s concerto on the strength of this prayer, later changing his mind in favor of the Leipzig Convention.[36]

4.3 Psalm 85 was also regularly read during special services in the Dresden Schlosskirche. It seems to have been a standard feature of the Landtag, being read in 1631, 1635, and 1640.[37] It also appeared at celebrations of the elector’s birthday and at the anniversary celebration in 1632 of the Battle of Breitenfeld, services where Schütz usually provided the music.[38] Although sermons published in Dresden during these years do not list the psalm as a main text, elsewhere preachers featured it at several important services of the era.[39] The text, it seems, was commonly associated with hopes for peace.[40]

4.4 In short, while Psalm 85 reflects the general political sentiment at Leipzig, at least at the convention’s end when the electors still thought their neutral federation would keep the peace, a quotation of a very common psalm buried in one prayer among several uttered at the ceremonies in Leipzig hardly makes sense as evidence that Schütz’s concerto was composed for or performed at the event.

4.5 Steude also based his argument on the manuscript transmission of the piece, but here again the argument is weak. The concerto survives in a single manuscript in Kassel, once part of the collection belonging to the court of the landgraves of Hesse-Kassel.[41] Steude tried to connect this manuscript to the Leipzig Convention via Landgrave Wilhelm V, who attended the meeting and who probably met Schütz there. A few years later, the landgrave wrote to Schütz asking for music, and according to Steude, this was the point when the concerto on Psalm 85 likely ended up in Kassel.[42] Yet although Schütz himself probably sent the concerto to Kassel, Steude provided no evidence that the landgrave first heard it in Leipzig and later asked for it. The landgrave did write to Schütz in 1635 but asked only for new music without mentioning individual pieces or the Leipzig Convention:

Because you have been accustomed to dignify this, our chapel, with your new compositions and pieces at all times but have not done so for some time, and we likewise would gladly have such new compositions in their entirety, this is our equitable and gracious disposition: that you would otherwise send us those pieces that you have recently turned out and yet are lacking in our chapel, and especially, too, whatever you further compose in the future.[43]

If anything, the landgrave seems to have wanted Schütz’s newest works, not those composed several years earlier.

4.6 The manuscript itself provides no links to Leipzig, and all evidence points rather to a later date around mid-century. The concerto is copied on Hessian paper and bears watermarks from around 1652–53.[44] Steude knew this but must have believed that it had been copied from an exemplar sent much earlier.[45] While we assume that the Kassel manuscript was copied from a source close to Schütz, if not stemming directly from the composer himself, we cannot assume that this copy entered the landgrave’s collection before 1638. It does not appear in the inventory drawn up in that year by the new chapel master, Michael Hartmann, which suggests that it probably entered the collection only later.[46] Another sign that the work dates from mid-century is a likely concordance in an inventory for the court chapel at Weimar, a collection compiled largely by Adam Drese from the late 1640s to 1662.[47]

4.7 In sum, most evidence points to a date for the concerto well after the Leipzig Convention.

4.8 In the end, we know only that the number of Dresden court musicians traveling to Leipzig in 1631 was theoretically large and diverse enough to mount a work like SWV 461, and it seems likely that the Dresden chapel master wrote something elaborate to suit the occasion. At the same time, we should not overlook the possibility that Schütz performed long existing music during the convention. In 1632 at the anniversary celebration of the Battle of Breitenfeld in Dresden, he performed his setting of Psalm 100 from the Becker Psalter (SWV 198), published in 1628.[48] At the Leipzig Convention, it is equally possible that Schütz performed existing music written by himself or his contemporaries.

5. Psalm 83 and the Leipzig Convention

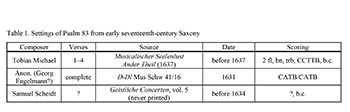

5.1 Using Steude’s own rationale, I suggest consideration of several settings of a different psalm. Psalm 83, “Gott schweige doch nicht also” (Keep not thou silence, O God), was the text on which Hoë preached at the convention’s opening service, and his remarks, as I showed above (par. 2.8), attracted controversy. Yet the eighty-third hardly enjoyed the same level of popularity as Psalm 85 in sermons, prayers, and music of this era, meaning that its appearance in Hoë’s sermon and in music around this time is less likely to be a coincidence. Few composers across the seventeenth century set the text in an elaborate manner. Apart from metrical paraphrases in psalters, I know of only seven substantial musical settings of this text, all from roughly 1630 to 1650. More specifically, the earliest three—a concerto by Tobias Michael, an anonymous eight-voice motet, and a lost concerto by Samuel Scheidt (see Table 1)—can be dated to the early 1630s and have indisputable Saxon provenance.

It hardly seems accidental that musical settings of this rare psalm suddenly appeared around the time when Hoë’s sermon shoved this text into the political spotlight. These settings, then, might prove more closely connected with the Leipzig Convention than Schütz’s Psalm 85.

5.2 Psalm 83 attracted the attention of Protestants, including Hoë, because it seemed to address the most serious political concerns driving them toward war.[49] (See Appendix 3 for the full text.) Lutheran writers of this era consistently interpreted this psalm as a prayer of the Church under persecution. They viewed the Hebrew people in the psalm as a type representing the Church, with their afflictions prefiguring the persecution of the Christian Church since New Testament times. In the psalmist’s enemies, Lutherans likewise saw their own opponents. In verse five, “For they have allied with each other and made a league against you,” Protestants could find allusion to the Catholic League, the confederation of Catholic states within the Empire, formed in 1609 in response to the Protestant Union.[50] Hoë himself also interpreted the psalm as an argument against the Edict of Restitution, finding a clear reference to one of its key points in verse twelve, where the psalmist’s enemies exclaim, “let us take the houses of God.”[51] Mimicking the voice of his Catholic opponents, Hoë linked this verse directly to the current outrage over the confiscation and conversion of church property:

And since the present enemies are not a hair better than those [from the Bible], so the Church of God also prays not unreasonably that our Lord God would do to the former as he did to the latter. Especially because they let it be known: “We want to take the houses of God. Where thus far God’s Word has been purely and sincerely preached, this shall no longer happen from now on. The houses of God, the temples, the churches, the schools, the diocese, the monasteries, which the people of God previously held, possessed, and used for God’s glory, these we want to take from them, strip from them, chase them out, and take all for ourselves.”[52]

Psalm 83, then, seemed to address Protestant grievances leading up to the Leipzig Convention in more specific ways than other psalms. Even if not every setting of this psalm consistently included the most politically contentious verses, any part of the psalm and its associations with the Leipzig Convention could turn the music into a timely statement about contemporary politics and religious persecution.

5.3 The three pieces listed in Table 1 all originated in Saxony: Tobias Michael and Samuel Scheidt worked in Leipzig and Halle respectively, and the anonymous motet comes from a set of partbooks once owned by the Saxon town of Schwarzenberg, south of Zwickau and Chemnitz near the border with Bohemia.[53] All three also date securely from the 1630s, most likely from early in the decade.

5.4 Though published in 1637, Michael’s concerto probably originated several years earlier. Like many printed collections of the time, both volumes of the Musicalische Seelenlust are a hodgepodge of works composed over several years and subsequently gathered for publication. The music in both volumes likely dates from the first half of the 1630s, especially since Michael’s preface mentions a paper shortage that delayed the second volume. Yet his concertos probably do not date from before 1631, since Michael apparently did not have musical duties before his appointment as Thomaskantor in Leipzig.[54]

5.5 That appointment raises the possibility of a direct tie between Tobias Michael’s Psalm 83 setting and the Leipzig Convention. Still, only circumstantial evidence puts Michael in Leipzig during the convention. He was appointed as Schein’s successor as city music director in late December 1630, Schein having died in November, and he officially took up that post in June 1631.[55] By late 1630, Michael apparently did not have clear duties at his earlier post at Sondershausen to keep him occupied. He also already had good connections with the city of Leipzig, chiefly through his brother Samuel, organist at the St. Nicholas Church since 1628.[56] Tobias was known well enough to the city council that they decided to forgo the regular audition and simply appoint him.[57] Moreover, by the time of the Leipzig Convention, Tobias already knew that he would soon take up his new post as city music director, the council having informed him of his duties, pay, and housing in late December 1630.[58] These clues leave open the possibility that Michael was in Leipzig and wrote music for the convention.[59]

5.6 While Michael’s concerto can be dated only approximately, the anonymous motet dates securely from early 1631. It survives in a single source, an incomplete set of manuscript partbooks in very poor physical condition once belonging to the city church in Schwarzenberg, since 1899 housed in Dresden (D-Dl Mus Schw 41).[60] The psalm is the sixteenth in a set of nineteen motets mostly for eight voices. Between 1612 and 1631, several Schwarzenberg copyists, including the cantor Matthäus Jahn, gradually assembled the partbooks, often dating the works as they progressed. The last few all date from the spring of 1631. No. 14 bears the date of April 7, 1631. No. 16, the Psalm 83 motet, was clearly entered sometime after this. (The alto part bears the year 1631, although the exact day and month, if written at all, are now illegible.[61]) Though the piece was presumably composed before being merely copied in Schwarzenberg, its style suggests a relatively recent work. While many of the other pieces in the set are in an older contrapuntal or polychoral style, the Psalm 83 setting alternates homophonic tutti ritornellos with concerted trios, a style increasingly common by the later 1620s.

5.7 The piece has sometimes been attributed to Georg Engelmann the Elder, apparently on the questionable basis of the preceding piece in the manuscript, which is securely attributed to Engelmann.[62] Engelmann was the St. Thomas Church organist, a musician whose ties to the Leipzig Convention and its opening service are stronger than those of any other musician outside the Dresden court chapel. Yet there is no pattern in these partbooks supporting such an attribution.[63] Moreover, the piece securely attributed to Engelmann is a motet in an older polychoral style, offering little common ground with the concerted sections in the Psalm 83 setting. Another candidate might be Heinrich Grimm, who worked in Magdeburg up until the city’s destruction in May 1631. Steude showed two other unattributed motets in the partbooks to be by Grimm (nos. 13 and 17). Both were copied around the same time as the Psalm 83 setting, raising the possibility that Grimm wrote this work, too. Yet either of these attributions would be purely speculative, and neither is supported by surviving inventories of Engelmann’s and Grimm’s works.

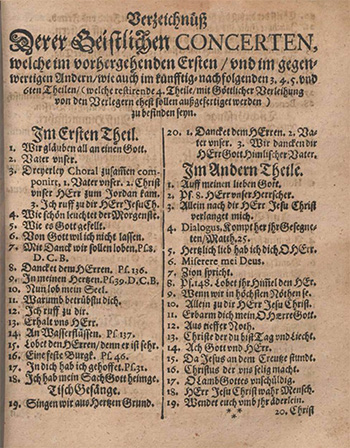

5.8 The third setting, by Samuel Scheidt, offers a different challenge since it no longer survives. But we can piece together enough information to suggest that it, too, probably dates from the early 1630s. It should have appeared in the fifth volume of Scheidt’s Geistliche Concerten, but the volume never made it to print.[64] We know of it because of an index of the complete series, including forthcoming volumes, which Scheidt included in the second volume from 1634.[65] A setting of Psalm 83 appears as no. 18 in the table of contents to volume five (see Figure 1, page three, right-hand column).

Of course, sometimes composers will advertise music they have yet to compose, but in this case, it seems that Scheidt actually composed this psalm by 1634 rather than merely planning it. The index for volume five offers an almost random assortment of pieces: the first fourteen are chorales organized alphabetically, followed by psalms, then Latin liturgical music. After this, clear organization breaks down. Had he structured the volume around the church year as he did for volume three, Scheidt easily could have drawn up this index before composing any of the music. As it stands, however, Scheidt’s index makes the most sense if we suppose he drew upon an already existing fund of miscellaneous works. A note at the end of his 1634 index (see the last page of Figure 1, above) seems to confirm this:

These sacred concertos listed here, which can be performed with a few vocal parts [i.e. as published], I have also composed for many parts in various sections, namely with 8 [and] 12 parts, two, three, four choirs, with symphonies, and all kinds of instruments, and also many tablatures to be used on the organ. Whoever desires to publish and print such works for the glory of God can have them from me anytime. Farewell.[66]

These works, presumably including those in the forthcoming volumes, were thus advertised as available in 1634, and it was probably a matter of seeing them to print. Volumes three and four, both of which ended up in print after being advertised in 1634, confirm this. In each case, the content of the published book matches the advertised index with only minor exceptions. All this suggests that Scheidt did not merely plan to write a setting of Psalm 83 but actually had one on hand by 1634, even if it never made it out of his personal library.[67]

5.9 Yet Scheidt’s original plan for the series, as advertised in volume one from 1631, did not include volumes five and six. Between late 1630—when volume one was already in press—and 1634, he must have decided to add two more volumes, one of which included a setting of Psalm 83. This timing, I think, is telling. It means that in the years or even months following the Leipzig Convention in early 1631, Scheidt thought it appropriate to add a setting of Psalm 83 to his expanding series. Unfortunately, too little is known of Scheidt’s whereabouts in early 1631 to connect him and his concerto to the Leipzig Convention.[68]

5.10 Besides these clues, the piece’s other features remain unclear, and we cannot know how many verses Scheidt set. Its scoring likely resembled the other pieces in his Geistlicher Concerten series: a concerto for up to six voices with basso continuo but without any other obbligato instruments (though as Scheidt himself advertised, he also composed added parts and ritornellos for some of these concertos). In any case, on stylistic grounds, this concerto is not likely to be the anonymous setting preserved in the Schwarzenberg collection discussed above. That motet does feature modern concerted duets, but the duet writing there is uniformly homophonic whereas Scheidt (in his surviving works) consistently introduces imitation. That the Schwarzenberg partbooks also preserve no other music attributed to Scheidt also speaks against his authorship.

6. The Hazards of Linking Music to Specific Occasions

6.1 Following Steude’s methodology, these points taken together apparently make a case for one of the Psalm 83 settings to have been performed at the Leipzig Convention. Yet that methodology is founded on a faulty assumption: that a piece of music whose text was also read, cited, quoted, or otherwise paraphrased prominently at an event was likely to have been performed at that event. This reasoning invites us to peruse liturgical books, prayers, sermons, and other documents surrounding a service, looking for references or quotations that match the musical repertoire. A motet whose text matches the Introit for the third Sunday after Trinity, the argument goes, must belong to that day, likely substituting for the chanted Introit.

6.2 In fact, we cannot assume that Lutherans or Catholics of this time chose music for a service because it matched one of the day’s prescribed scripture readings or liturgical texts. In practice, as David Crook has shown, they engaged in considerable exegetical creativity when deciding where in the liturgy to perform motets. Crook examined Johannes Rühling’s Tabulaturbuch (Leipzig, 1583), which assigns various motets to specific occasions in the liturgical calendar, sometimes contradicting the assignments by modern scholars. Crook’s conclusion is worth quoting at length:

Rühling made use of some motets for which modern editors could provide no liturgical assignment and … some of his assignments contradict information they provided. It demonstrates, in other words, that liturgical assignment did not govern his selection of particular motets for particular occasions. It also reveals that our relationship to these texts differs fundamentally from [Rühling’s]. When confronted with a motet text, we search through liturgical sources until we locate a text—or a combination of texts—that matches the motet text, and then we record where we found it. We engage, that is, in a process of labeling and classification…. For Rühling, the process was different. He read his texts, contemplated their meaning, and determined how he might use them to gloss, amplify, and contextualize the principal themes of the liturgy. His primary concern was not with the provenance of texts but with their exegetical potential.[69]

6.3 We can support Crook’s findings by turning to specific orders of service recorded in Dresden during Schütz’s tenure. In several prominent cases, the music performed at these services never matches the words of the prayers, readings, or sermons that surrounded it. The best example is the 1632 anniversary celebration of the Battle of Breitenfeld in the Schlosskirche in Dresden, the occasion for a performance of Schütz’s Saul, Saul was verfolgst du mich? Thanks to a manuscript order of service recovered in 2008, we know that a concerto with this incipit appeared after the Magnificat at vespers on the day of the celebration. But without that source, the concerto would be impossible to pin to the event by finding a reference to its text (Acts 9) elsewhere in the services. The sermons, prayers, and official printed orders of service never quote, cite, or otherwise even allude to Acts 9. At the same time, as I have suggested elsewhere, Schütz’s Saul makes perfect sense at the celebration from an exegetical standpoint, providing a gloss on the festival’s main themes.[70]

6.4 In other cases, we know that a biblical passage was given great prominence in a service as a sermon text or reading, but the musicians still did not perform anything based on that text. The 1631 Landtag again makes an excellent case. Despite being read in its entirety and then quoted at length at the end of Hoë’s sermon, Psalm 85 did not number among the pieces of music performed that day. Instead, Schütz performed a concerto on Es stehe Gott auff.[71] We might even speculate that in such cases, when a biblical text already appeared in prominent places in a service, musicians had greater incentive to choose a different text for the sake of variety.

6.5 The lesson, then, is that when trying to link music to events or the liturgy in general, we need to treat the official prayers, sermons, and scripture readings with caution. Because Lutherans chose music based on exegetical grounds, the other words read or sung during a service might not match those in the music exactly. If we want reliable evidence for music heard on a specific date and time, we must turn to other kinds of documents such as orders of service or eyewitness accounts, and in the early modern era, that kind of proof unfortunately almost never turns up. In the case of the Leipzig Convention, the main chronicles and archival documents associated with the event have been raked over for years without getting much closer to the exact music heard by the Empire’s Protestants assembled there in early 1631.

6.6 While this loss is lamentable, if hardly surprising, my own answer has been to take a different approach to working with this repertoire. Whether or not we can identify the occasions on which Schütz and his contemporaries performed particular pieces of music, we can certainly profit from exploring the meaning invested in those pieces. To do this, we can look at the broader contexts in which Lutherans used the biblical texts that were set to music—not only in the regular liturgy but in a variety of situations: theological, devotional, polemical, and political. Here, for example, Hoë’s sermon opening the Leipzig Convention provides a window into the contemporary political significance of Psalm 83; that significance might in turn be applied broadly to musical settings composed for a variety of purposes and occasions around that time. In the same vein, we might look at the contexts in which Schütz’s contemporaries used Psalm 85, not to document when he performed his concerto but to elucidate its contemporary significance. In short, although we may never know when Schütz and his contemporaries performed most of their music, we can still begin to gauge the music’s significance to its earliest listeners, and this can prove rewarding and illuminating.

Acknowledgments

I owe many thanks to Joshua Rifkin for thoughtful discussions related to this subject; to the staff at the Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden, especially Dr. Karl Wilhelm Geck; and to the staff at the Stadtarchiv and Universitätsbibliothek Leipzig. Portions of this article were presented at the annual meeting of the American Musicological Society in 2013.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Psalm 85: text and translation

Appendix 2. Closing prayer of the Leipzig Convention

Appendix 3. Psalm 83: text and translation

Figures

Figure 1. Scheidt, Geistlicher Concerten … Ander Theil: multi-volume index

Tables

Table 1. Settings of Psalm 83 from early seventeenth-century Saxony