The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Positioning the references: References may appear either at the right-hand side or at the foot of the screen. Readers can change the position of the references by changing the width of the window. To change the width, either drag the edge of the window or adjust the magnification (Ctrl+ or Ctrl- on PC, Cmd+ or Cmd- on Macintosh).

Reading the references: Use the note numerals to move back and forth between the main text and the references. The links work in both directions. The linked object will move to the top of its frame.

Opening linked files: In recent issues of JSCM, most examples, figures, and tables, along with their captions, open as overlays, covering the text until they are closed. Nevertheless, readers have choices. In most browsers, by right-clicking the hyperlink (PC or Macintosh) or control-clicking it (Macintosh), you can access a menu that will give you the option of opening the linked file (without its caption) in a new tab, or even in a new window that can be resized and moved at will.

Printing JSCM articles: Use the “print” link on the page or your browser’s print function to open a print dialog for the main text and endnotes. To print a linked file (e.g., an example or figure), either use the “print” command on the overlay or open the item in a new tab (see above).

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © 1995–2025 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 26 (2020) No. 1

Protestantism, Patriotism, and the Idea of Germanness in a Seventeenth-Century Singspiel: Neu erfundenes FreudenSpiel genandt Friedens Sieg (1642)

Hannah Spracklan-Holl*

Abstract

This article explores the idea of Germanic identity in the mid-seventeenth century as expressed in the Singspiel Friedens Sieg, performed at the ducal palace in Braunschweig (Brunswick) in 1642, with text by Justus Georg Schottelius and music by Duchess Sophie Elisabeth of Braunschweig-Lüneburg. Ideas of Germanness are particularly evident in works by members of the German literary societies of the time. These works include peace dramas, plays that used the Thirty Years War as their subject matter to espouse patriotic values. In the peace drama Friedens Sieg, Schottelius’s moral messages are supported and enhanced by Sophie Elisabeth’s music.

2. Literary Societies and Seventeenth-Century German Patriotism

3. The Peace Drama of the Mid-Seventeenth Century

4. Anti-Foreign Sentiment as an Aspect of German Patriotism

5. The Politics of Performance

6. Friedens Sieg: Fiction as Reality

1. Introduction

1.1 The Thirty Years War was one of the most devastating conflicts in early modern Europe. In addition to its social, economic, and artistic consequences, the war and its outcomes played a significant role in the consolidation of seventeenth-century German patriotism. At least at first, it was a Germanic war between Protestants and Catholics who strove to enforce their own interpretations of the Peace of Augsburg of 1555, which allowed rulers to choose either Lutheranism or Roman Catholicism as their official confession and that of their subjects under the principle of cuius regio, eius religio (the religion of the ruler is the religion of the realm). Confessional issues were thus an important aspect of the war, and they remained a potent issue after it ended. For German-speaking members of the Protestant nobility, the close relationship between their confession and their patriotism was reflected partly in their promotion of the standardized and widespread use of German as a national language, which was evident in the formation and activities of German-language literary societies. In the Duchy of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, an early end to the Thirty Years War was marked by the signing of the Treaty of Goslar in 1642 by the Guelph duke, August the Younger. August had received his dukedom in 1634 after the death of his predecessor Friedrich Ulrich, the last member of the line of the Middle House of Brunswick; however, August was unable to take up residence in the duchy’s capital, Wolfenbüttel, due to the war—in particular the occupation of Wolfenbüttel by an imperial garrison starting in 1638.[1] In order to regain possession of Wolfenbüttel, August signed the Treaty of Goslar, which allowed him to return to his capital on the condition that the Guelphs reduce the size of their armies and cease negotiations with Sweden.[2]

1.2 The garrison did not leave Wolfenbüttel until September 1643; nevertheless, in 1642 the treaty was celebrated at the Dankwarderode palace in Braunschweig with a performance of Neu erfundenes FreudenSpiel genandt Friedens Sieg (The Triumph of Peace), a Singspiel with text by Justus Georg Schottelius and music by Duke August’s wife, Duchess Sophie Elisabeth of Braunschweig-Lüneburg. It comprises three acts, separated by Zwischenspiele (interludes) that reiterate the moral message of the preceding act. Sophie Elisabeth’s music—mainly strophic songs—appears in the two Zwischenspiele and in Act 3.[3] This article aims to show how Protestantism and patriotism intersected in seventeenth-century German cultural narratives and helped to reinforce political power in the immediate aftermath of the Thirty Years War, with particular reference to the characterization of August and Sophie Elisabeth in this Singspiel’s musical sections.

1.3 In the seventeenth century the present-day conception of a geographically unified “Germany” did not exist. Rather, the German-speaking lands consisted of a large number of distinct domains, including imperial free cities, duchies, principalities, and bishoprics, among others. However, as this article discusses the idea of Germanness, I will use the terms “German” and “Germany” to describe people and territories within the German-speaking lands. I am not including discussion of Catholic territories here, as the idea of Germanness I am drawing on in this specific era included Protestantism as an essential characteristic. For Benedict Anderson, nationalism is defined as the devotion to the interests of a particular nation, while the nation is “an imagined political community” whose members “will never know most of their fellow-members … yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.”[4] Anderson makes particular reference to the eighteenth century as a pivotal period in the emergence of nationalism focused on nation states, and as we have seen, in the seventeenth century, there was no German nation state to which nationalists could devote themselves. Nevertheless, the German Protestants were certainly a “nation” as Anderson defines the word, and it will become clear that some sentiments expressed in Friedens Sieg have much in common with his theory of nationalism. In any case, I have chosen instead to use the words “patriotic” and “patriotism” to describe these sentiments.[5]

1.4 In order to interpret Friedens Sieg as a tool for promoting an ideal of Germanness, it is important to understand the contexts from which this ideal originates. First, I will discuss the emergence of German-language literary societies and the views of their members regarding the values and characteristics of an ideal German. Following this, I will assess the characteristics of what Leon Stein calls “peace dramas,” often written by members of literary societies, and the role they played in espousing these values.[6] Finally, I will examine how moral messages are highlighted in Friedens Sieg through its use of music and how this music contributed to an overall endorsement throughout the Singspiel of Duke August’s leadership of the Duchy of Braunschweig-Lüneburg.

2. Literary Societies and Seventeenth-Century German Patriotism

2.1 Seventeenth-century Protestant Germany, despite geographical division and ideological disjunction between Lutherans and Calvinists during wartime, was linked by a desire for political and ideological bonds between territories that were determined, first and foremost, by their confession.[7] These ideas had been prominent in the German-speaking lands since the beginning of the Reformation; however, they found particularly strong expression in the works of members of German literary societies. The largest of these societies, the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft (Fruitbearing Society), was founded on August 24, 1617, almost one hundred years after Luther’s proclamation of his ninety-five theses on indulgences.[8] While this connection may be pure coincidence, it is clear that from the beginning of the seventeenth century the ideas and aims of literary societies had a strong, Lutheran theological foundation. As Koppel Pinson recognized, qualities of Lutheran pietism, including “strong emotional fervour, moral purity … and the cultivation of the German language,” transferred to late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century German nationalism.[9] The connection between Protestant theology and ideas of German nationhood has also been noted by Ulinka Rublack, who pinpoints its origin in the nineteenth-century writings of Leopold von Ranke, which view the rise of Prussia as an opportunity to “create a politically unified, strong, united Protestant state.”[10] Neither Pinson nor Rublack, however, pays close attention to the noteworthy presence of these ideas in the work of members of seventeenth-century literary societies.

2.2 The connection between literary societies and seventeenth-century patriotism is particularly clear toward the end of the Thirty Years War. As patriotic sentiment intensified in the last decade and early aftermath of the war, the religious and moral underpinnings of literary societies such as the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaftbecame more strongly linked to an ideal of Germanness. The clearest evidence for this is the formation of two new literary societies in the last decade of the war, the Deutschgesinnte Genossenschaft (German-minded Cooperative), founded in 1643 by Philipp von Zesen, and the Pegnesischer Blumenorden (Order of the Flowers of Pegnitz), founded in 1644 by Georg Philipp Harsdörffer and Johann Klaj, and revived after 1658 by Sigmund von Birken.[11] These two societies joined the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft, which by this time was flourishing and would, at its peak, have 890 members.[12] While the Deutschgesinnte Genossenschaft and the Pegnesischer Blumenorden eventually counted both men and women among their members, the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaftwas a men-only society for the duration of its existence. Its establishment in 1617 was thus the catalyst for the formation of two women-only societies, in 1617 and 1619: the Güldene Palm-Orden (Order of the Golden Palm, also known as the Noble Académie des Loyales), which posited itself as a sister society to the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft, and the Tugendliche Gesellschaft (Virtuous Society).[13] The poets, scholars, princes, princesses, theologians, and noble men and women who were members of these societies—including Duke August, Duchess Sophie Elisabeth, and the playwright Schottelius—imagined an ideal of Germanness characterized by its place at the intersection of religious and moral regeneration and linguistic and cultural unity.

2.3 In their imagination of an ideal of Germanness, patriotic members of literary societies also rejected foreign influence, which they saw as being partly responsible for the widespread destruction caused by the war.[14] In the view of these patriots, however, the German people—a group that included the patriots themselves—were also to blame for the effects of war. They were seen as weak-willed, for rather than defending themselves against the threat of foreign invasion, they allowed this invasion to occur. This was particularly pertinent in Wolfenbüttel, where the actions of August’s predecessor, Friedrich Ulrich, led to the establishment of an imperial garrison in the town. The writings of Schottelius and other members of the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft reflect this sentiment. In Schottelius’s Der nunmehr hinsterbenden Nymphen Germaniae elendeste Todesklage (Dirge for the Dying Nymph Germania, 1640), for example, the allegorical figure of Germany appears as a haggard queen who laments the presence of foreigners on her land and the introduction of their words into the German language.[15] Similarly, in Johann Rist’s Das friedewünschende Teutschland (The Peace-loving Germany, 1648), Germany is “wretched and miserable” and “laments its broken state.”[16] Even after the Treaty of Goslar was signed, Schottelius still saw contemporary Germany as immoral, writing in the preface to Friedens Sieg: “In our time the world is overflowing with the sinfulness of evil, and it is not getting better.”[17]

3. The Peace Drama of the Mid-Seventeenth Century

3.1 Friedens Sieg fits broadly into the patriotic German literature of the seventeenth century, which found expression in both theatrical and poetic forms and is characterized by generally anti-foreign and consciously German sentiment. Many of the works that contribute to a body of seventeenth-century patriotic German literature were written by members of the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft: for example, the 1620 poem Ein Gebet/ daß Gott die Spanier wiederumb von Rheinstrom wolle treiben (A Prayer that God will again drive the Spaniards from Rheinstrom) was written by Martin Opitz (1597–1639), and the 1636 sonnet Threnen des Vatterlandes (Tears of the Fatherland) by Andreas Gryphius (1616–54).[18] Both men were members of the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft, with the society names “Der Gekrönte” and “Der Unsterbliche,” respectively.[19]

3.2 For members of the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft who contributed to this body of literature, artistic and intellectual resistance to foreign invasion was concentrated on the simultaneous “[purification] of [both] the German language and morals.”[20] Peace dramas such as Friedens Sieg and Das friedewünschende Teutschland dealt specifically and explicitly with the Thirty Years War, using their subject matter to espouse moral messages about its effects on Germany, German language, and culture, in line with the aims of the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft. One way in which patriotic writers of peace dramas aimed to do this was by presenting an image of an idealized past in their works to contrast with what they perceived as the shameful present. In Friedens Sieg, “the personification of former German glory” is the historical character Arminius.[21] At the Battle of Teutoberg Forest in AD 9, Arminius led 10,000 Germanic soldiers in their defeat of the 20,000-strong Roman army, halting Roman expansion along the Rhine and keeping these territories solely Germanic. For Schottelius, Arminius’s virtuous bravery was an ideal cornerstone of Germanness and thus served as an example to his audience. Arminius is first escorted into the action of Friedens Sieg by Mercury, who calls him a “strident war hero” and the “golden head and immortal ornament of all German dukes,” positioning him as a Germanic ideal to which Schottelius expected his audience to strive.[22] It is thus no coincidence that Arminius features in a Singspiel written to celebrate another instance of Germanic wartime success: in this case, the driving out of Catholic imperial troops from a Protestant duchy.[23] As Roger Christian Skarsten points out, the theatrical use of the historical figure and character of Arminius is not unique to Friedens Sieg.[24] Arminius appears in musical-theatrical works from the seventeenth to the twenty-first centuries, often as a device for promoting a German national identity. Friedens Sieg represents the first use of Arminius in this way; however, his presence is only one aspect of the patriotic rhetoric evident in the work.

3.3 In Friedens Sieg, Arminius is particularly linked with faith and piety. Schottelius makes strong connections between Arminius’s bravery and his religious virtue, stressing his position as a Christian defender of Germany who praises the “immortal gods” and values “heavenly rest.”[25] As Sara Smart points out, both courage and faith were associated with peace in seventeenth-century Germany, for they played a significant role in establishing Germany’s former position as the head of Christendom.[26] By characterizing Arminius as the representative of Germanness in Friedens Sieg, Schottelius urges his audience to recognize that in order for Germany to be restored to its former glory in the aftermath of the Thirty Years War, its people must have strong faith and morality, in addition to military might.

4. Anti-Foreign Sentiment as an Aspect of German Patriotism

4.1 Peace dramas by Johann Rist and Sigmund von Birken, also members of the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft, echo this sentiment and tend to follow the same dramatic structure as Friedens Sieg. Beginning with a prologue that emphasizes the author’s patriotic and religious aims, peace dramas continue to tell the story of a Germany that has been destroyed by war, which, with the encouragement of old heroes appearing as defenders of German identity and liberty, undergoes a conversion. Following this rebirth, peace, unity, and harmony are revived, leaving the drama’s audience with an overall message of both cultural and spiritual redemption. Along with the idea that Germany could be renewed through the purification of morals and language was the denouncement of other cultures and languages, particularly French. Leon Stein claims that anti-French sentiment in peace dramas indicates a rejection of courtly customs among members of the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft. However, the society’s origins and strongest centers were at Protestant courts, and the majority of its members, including Schottelius, Rist, and Birken, were noble themselves or closely associated with courts, often as employees such as court tutors.[27] Many peace dramas, including Friedens Sieg, were performed at court, both by and for a courtly audience. It thus appears that patriotic expression in these works was more indicative of a desire for courts with a robustly Germanic cultural foundation, rather than a desire to renounce court society and culture completely.

4.2 It is useful to note here that while the ideas shared by Schottelius and other members of literary societies regarding the nature of Germanness found increased expression in the aftermath of the Thirty Years War, they have a much longer history. In many of his works, Schottelius drew on the observations of the Roman senator and historian Tacitus in Germania, which was written around AD 98 but did not reappear until 1425.[28] In Friedens Sieg Schottelius uses two conceptions of Germanness that are prominent in Germania to promote the past and criticize the present: the idea of a self-contained German nation and people, and the Arminius narrative. In Germania, the German people are described as “entirely unalloyed by admixture with immigrant tribes” and thus have “precisely the same physical characteristics” as each other.[29] This idea is reflected in the staunch anti-foreign sentiment clearly present in the first act of Friedens Sieg. Here Schottelius contrasts the German people with the French, the Spanish, and the Turkish in those other cultures’ worship of the goddess Fortuna, whose “fickleness and omnipotence in worldly affairs” Schottelius sees as the catalyst for war.[30] While the French, Spanish, and Turkish hope to expand their empires by praising Fortuna, whom Schottelius characterizes as lecherous and ridiculing, the German remains independent.[31] He acknowledges that he has been swayed by Fortuna in the past—reflecting Schottelius’s criticism of the German people’s role in the Thirty Years War—but refuses her gifts and promises of victory and instead blames her for the devastation caused by the war.[32] For Schottelius, the worship of the goddess Fortuna and the worldly, irreligious vanity she represents was the root cause of destructive conflict.

4.3 As for the Arminius narrative, its focus on a Germanic ideal strongly resonates with Schottelius’s anti-foreign sentiment in Friedens Sieg with regard to the German language. For Schottelius, the first step to regaining the glory of the past was the restoration of widespread use of German, unfettered by foreign words. The centrality of language restoration to the seventeenth-century German nationalist cause and its close relationship to religion cannot be overstated. To those at the center of this movement the German language became not only the cornerstone of the renewal of German culture and an important tool with which to combat foreign influence but the “embodiment of national virtue and character.”[33] This was in line with the belief of the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft in linguistic reform, and had a particularly strong connection to the cultural aspirations of the Wolfenbüttel court, at which Schottelius worked in varying roles from 1638 until his death in 1666.[34] Duke August, known in the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft as “The Liberator” (“Der Befreiende”), assisted with the revision of several of Luther’s translations of Bible Gospels and Epistles, using grammatically and stylistically reformed German in order to make these passages properly understood and thus promote piety throughout his court through their reading and recitation.[35]

4.4 In several of his writings Schottelius clearly links the German language with military might, valor, and upstanding morality, values also seen in the Arminius narrative. At the beginning of Der teutschen Sprach Einleitung (1643), for example, Schottelius describes how the influence of the German language was synonymous with the success of the German-speaking lands in military conflicts, making reference to the choice of Charlemagne and Rudolf I to use German in official matters of state.[36] In Friedens Sieg, Schottelius promotes the German language through the experiences of Arminius and his compatriot Heinrich der Finkler, who was the king of East Francia from 919 until his death in 936. Both figures are dressed in Germanic clothes, highlighting their roles as warriors and leaders: Arminius wears bucket-top boots, a winged helmet, and what appears to be an animal skin wrapped around his shoulders as a cloak, while Heinrich wears a crown, cloak, and carries a scepter (Figure 1).

When these figures arrive in Germany in the second act of Friedens Sieg, the allegorical figure of Righteousness (Gerechtigkeit) endorses them as chivalrous heroes, known and loved by the gods for their heroic and victorious deeds during wartime. As they acclimatize themselves in a war-torn Germany they find unrecognizable, Arminius and Heinrich are greeted by Bolderian, a “cavalier” whose German speech is peppered with French words, and whose feathered hat, boots, and stance indicate his preoccupation with appearance and adherence to contemporary trends, in clothing and in speech (see Figure 1 above).[37] While Bolderian’s visual difference from Arminius and Heinrich is striking, it is his use of language that the two patriotic Germans find most difficult to understand. Schottelius’s portrayal of Bolderian is a comment on the influence of foreign culture and language in the German-speaking lands and, more specifically, a critique of the rising Frenchified courts. For Schottelius, the adoption of aspects of French language and culture by these courts was seen as “an abuse encouraged by the presence of foreign armies on German soil” and was synonymous with irreligion, immorality, and egocentricity.[38] Similarly, Arminius and Heinrich are perplexed by the speech of other contemporary Germans, including a peasant; again this demonstrates Schottelius’s dismay at the lack of linguistic unity among seventeenth-century Germans.

4.5 Other peace dramas written by members of literary societies express similar sentiments to those Schottelius conveys in Friedens Sieg. Rist’s Das friedewünschende Teutschland provides an example of the shared patriotic stance among members of literary societies, and how this was commonly expressed to a wider audience. Rist’s drama, like Friedens Sieg, features Arminius, this time confronted with the allegorical figure of Germany as a queen dressed in foreign fashions and speaking a hybrid form of German full of foreign phrases.[39] As in Friedens Sieg, Germany is eventually converted to Protestant piety and the proper use of the German language. Both dramas, written before the end of the Thirty Years War, demonstrate the didacticism of much mid seventeenth-century German theater. Schottelius, in particular, saw the stage as an ideal means by which to communicate Christian morality.[40] In the preface to Friedens Sieg he speaks to the usefulness of the peace drama in educating an audience about their role in the terrible state of the world as well as their potential to improve it, writing that “theatrical dramas are known as an imitation of life, a mirror of the habits and manners of the world and of the truth that is to come.”[41] Friedens Sieg is set apart from other peace dramas, however, by its overall endorsement of a specific ruler, August, who played an important role in signing the Treaty of Goslar, had a strong association with communities of Protestant nationalists, and was described within those communities as “The Liberator.” Throughout Friedens Sieg, but particularly in its musical interludes, the duke is thus depicted as a model leader and an example of ideal Germanness in the aftermath of war.

5. The Politics of Performance

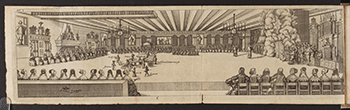

5.1 I now turn to how the depictions of August and Sophie Elisabeth in Friedens Sieg consolidated their status within the court’s hierarchy and in a wider context by promoting a distinctively German court culture at Wolfenbüttel, characterized by its Protestant faith and patriotic leanings. Every element of the Singspiel’s production contributed to the portrayal of the ducal couple. As has been noted in numerous studies of seventeenth-century theatrical productions, the physical placement of the duke and duchess in the audience was highly significant.[42] While in some instances the ruler’s position above his subjects is obvious from his place in the seating arrangement—for instance, Ferdinand III’s central, raised throne in the audience for La Gara, performed in Vienna in 1652—in Friedens Sieg August and Sophie Elisabeth are seated on the same level as both fellow audience members and the performers, but in the best seats directly opposite the actors’ entrance. Alongside the duke and duchess are important court members and guests, including Julius Heinrich of Saxony (r. 1656–65), Friedrich Wilhelm of Brandenburg-Prussia (r. 1640–88), August’s heir Rudolf August (r. 1666–1704), and the ducal couple’s other children. The other audience members are arranged along the two other walls of the hall, with those of higher rank seated closer to the duke and duchess (Figure 2).

5.2 This seating arrangement, while providing an example of how the court’s hierarchical structure extended into court entertainment, becomes particularly significant in the interludes between the Singspiel’s acts, called Zwischenspiele. The first act of Friedens Sieg features a grand entrance speech by Fortuna, in which she proclaims herself the “queen regent of the entire world” after addressing her audience as “mortal men, miserable scoundrels of the earth.”[43] Mars enters, followed by a Spaniard, a Turk, and a Frenchman, who are assured of Fortuna’s favor by Mars and grovel before Fortuna. A German, on the other hand, accuses Fortuna of the horror that has befallen his homeland, and begs to be released from the oppression of Fortuna and Mars, favoring virtue and peace over the fickleness of Fortuna and the wanton destruction of Mars.[44] In the first Zwischenspiel, the then six-year-old Ferdinand Albrecht, son of August and Sophie Elisabeth, takes the role of Cupid. He flies into the scene pushing a large globe, taking up his position in front of the Singspiel’s most distinguished audience members, and, during the introduction to his song, pulls objects with which he is associated—the bonds of love, hearts, arrows, and his bow—from the globe.[45] During the song, sung by one of the court’s Kapellknaben, Ferdinand Albrecht as Cupid aims his arrows at the women, including Sophie Elisabeth, Duchess Anna Sophia, who was the widow of the last member of the Wolfenbüttel line of the House of Guelph and is also Friedens Sieg’s dedicatee, and Anna Sophia’s sister Catharina, who was married to the pro-imperial Prince Franz-Karl of Saxe-Lauenburg (who converted to Catholicism in 1637).[46] Each of the seventeen strophes of Cupid’s song describe his actions as well as the qualities of his arrows. The attributes of each of these arrows—for example, the gold arrow brings joy, the lead arrow brings pain, and another is devoid of loyalty and love—make a comment on love’s varying fortunes while the Liebesband that ultimately unites all hearts emphasizes Cupid’s control over love.

5.3 While the aspect of audience participation in this Zwischenspiel gives it a lighthearted feeling, the engraving that accompanies it highlights the interactive relationship between Friedens Sieg and its intended audience. This takes place on two levels. Firstly, Cupid’s actions draw attention to the marriage alliances between dynastic houses. Secondly, the casting of Ferdinand Albrecht as Cupid, as the first son born to both August and Sophie Elisabeth, draws particular attention to the success of the marriage between the ducal couple as compared to the marriages of their noble visitors. This is particularly pointed, given Franz-Karl of Saxe-Lauenberg’s recent conversion to Catholicism. More than twenty-four years after Friedens Sieg’s first performance, Ferdinand Albrecht and his elder brothers Rudolf August and Anton Ulrich would squabble over the dukedom after August’s death in 1666. This conflict resulted in Ferdinand Albrecht receiving the secundogeniture of Braunschweig-Bevern and thereby waiving his right to rule within Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel. These events could not have been known in 1642, however, and his role in Friedens Sieg’s first Zwischenspiel nevertheless affirms to Friedens Sieg’s audience the “inner continuity of ancestry within the larger duchy,” consolidating his parents’ leadership role as well as pointing towards his own future position as a leader.[47]

5.4 Immediately following Cupid’s song is a quartet featuring two shepherds and two shepherdesses: Aritoson and Sylvosa, who are devoted to Virtue, and Eutychas and Strephone, who praise Fortune. The two pairs sing against each other antiphonally for seventeen strophes, each defending Virtue and Fortune respectively. Finally, after Aritoson and Sylvosa sing a strophe alone, Eutychas and Strephone are converted to the merits of Virtue and the four shepherds sing a final verse praising morality and peace, declaring that they will be celebrated with a little song accompanied by pipes. The use of shepherds as the quartet here and the use of pipes to accompany and characterize them is significant, as it allows Schottelius and Sophie Elisabeth to demonstrate the extent to which immoral worship of Fortuna has permeated all social classes in Germany, not only the nobility for which the Singspiel was performed.

5.5 The second act centers on Arminius and Heinrich der Finkler and their experiences in a Germany that is, to them, unrecognizable. The Zwischenspiel following this act thus focuses on restating the widespread sorrow throughout Germany caused by the Thirty Years War, in which the German people themselves played a part. This is highlighted by two songs: the first is sung in a “pitiful voice” by the forest nymph Friedeguld, played by a member of the Wolfenbüttel Kapellknaben, lamenting the poverty, famine, death, and injustice cause by the war.[48] The allegorical figures of each of these are then announced with a trumpet fanfare and process onto the stage accompanied by Mars before singing a quartet about their individual and collective roles in the war. After singing they are led away by Mars, and Friedeguld closes the Zwischenspiel with ten short strophes begging for peace.

5.6 The splendor of Friedens Sieg is best illustrated in its third act, when the goddess Peace, another role assumed by Ferdinand Albrecht, is the focus of a magnificent procession (Figure 3).

It is led by the allegorical figure of True Reason, who is dressed in a costume covered in crystals and mirrors—evoking Schottelius’s idea of peace dramas as “a mirror of the … truth”—while Peace is dressed entirely in golden robes and rides a chariot.[49] True Reason introduces the other members of the procession who surround Peace’s chariot: the allegorical figures of Justice, Virtue, Piety, Unity, and Fortitude; the nine Muses; Ceres, the goddess of fertility and prosperity; and Arminius and Heinrich der Finkler, whose pleas for peace in Act 2 have been answered by Peace’s arrival. Act 3 contains seven musical numbers sung by the Muses, played by members of the court Kapelle. In the song “Güldene Friede,” for example, the Muses Euterpe, Calliope, Melpomene, and Thalia compare the effects of war and peace in each strophe. The song finishes with a strophe about peace alone, in which the Muses proclaim that peace brings “well-being, celebrations, honor, joy, and salvation” to the court.[50]

5.7 Act 3 can be seen as an altered mirror image of Act 1: the procession of Fortuna from the first act is replaced by a procession of Peace in the third, and the accompanying allegorical figures are also replaced.[51] Act 3, however, is very different in character and tone from the first and second acts. Its grandiosity and magnificence are emphasized both by the contrast between the acts that bookend Friedens Sieg and by Act 3’s musical content. Prior to the third act, music is present only in the Zwischenspiele and not in the acts themselves.

5.8 Moreover, the use of music in this specific dramatic location creates a parallel between the action of the Singspiel and the progress of Wolfenbüttel’s actual court life—i.e., the role of the arts at the court from the end of the sixteenth century until the 1640s. Duke Heinrich Julius, who was Wolfenbüttel’s reigning duke from 1589 until his death in 1613, paid considerable attention to the relationship between the court’s artistic and intellectual life and its political position. While the Thirty Years War certainly affected Wolfenbüttel’s music and arts, these were declining even before the war during the reign of Heinrich Julius’s successor, Duke Friedrich Ulrich, who held leadership from 1613 until 1634. Whereas Heinrich Julius employed Michael Praetorius as his Kapellmeister, wrote eleven plays, and had a close relationship with the Jacobean theater troupe Worcester’s Men, Friedrich Ulrich’s reign was dominated by wartime concerns. Friedens Sieg’s initial performance, therefore, heralds the beginning of a new phase in Wolfenbüttel’s artistic and intellectual life as well as its political, linguistic, and moral life. As Germany is restored to its former glory within the action of Friedens Sieg, so too is Wolfenbüttel, through the Singspiel itself and the role of August and Sophie Elisabeth in its production.

6. Friedens Sieg: Fiction as Reality

6.1 To illustrate that last point, I will first outline the role of Sophie Elisabeth’s music in the Zwischenspiele and then turn to the third act as the Singspiel’s culmination of political spectacle. Two aspects of Sophie Elisabeth’s music promote the patriotic, Protestant ideas expressed in Schottelius’s text and the characterization of August as an ideal Germanic leader: the type of musical setting—in general either declamatory or dance-like—and the location of these different settings within the play. .

6.2 The music in Friedens Sieg’s two Zwischenspiele is scored only for voice (or voices) and basso continuo. The single-voice strophic continuo songs in particular bear a resemblance to those in other peace plays written by members of literary societies, for instance Rist’s Das friedewünschende Teuschland, discussed above, and his Das friedejauchende Teutschland (1653).[52] Most of Sophie Elisabeth’s settings conform to the natural stresses of the German language and use easily memorable tunes, thus “[fitting] the means and ends of Luther’s prescriptions for music.”[53] Yet her single-voice settings in the second Zwischenspiel go further than that. In “Angst und Qual,” sung by the nymph Friedeguld, for instance (where, as Karl Wilhelm Geck has observed, six-line strophes in trochaic tetrameter offer “considerably more scope” for expression than those songs with two- and four-line strophes),[54] Sophie Elisabeth uses suspiratio figures and an echo device as part of her construction of a lament. These devices are also evident in “Ich der hässlich bleiche Tod,” for four voices and continuo, and “Auf Echo und sprich mir nach,” both also in the second Zwischenspiel. In “Angst und Qual” (Example 1), as Geck observes, Sophie Elisabeth uses suspiratio figures twice, in bar 1 and bars 7 and 8[55]—sighs expressed by rests that fall on the beat, resulting in a displacement of the vocal part. Along with these figures, she uses chromatic alteration of the melody line (particularly in bars 8, 9, 16, and 17), which Geck describes as a passus duriusculus. Together, these two musical-rhetorical figures, along with the echo effect at the end of the refrain, create a musical affect that parallels Schottelius’s text.[56]

As we have seen, the songs in the second Zwischenspiel reiterate the moral message of the second act, in which the old Germanic heroes Arminius and Heinrich der Finkler despair over the war-torn Germany in which they find themselves. Sophie Elisabeth’s settings thus represent the negative effects of war, which, the play contends, is the embodiment of “lust and sin” and is caused by worldly vanity.[57]

6.3 The importance of the moral messages conveyed in Friedens Sieg’s Zwischenspiele provides a useful link between Sophie Elisabeth’s affective settings and ideas regarding music in Protestantism. Luther’s prescriptions for music suggest that, while “all the notes and melodies [should] center on the text” (a quote included in Praetorius’s Syntagma Musicum, part 1, of 1615), music plays an active role in “[bringing] the text to life” through settings that not only support but also enhance the text.[58] Luther goes further in his preface to Joseph Klug’s Begräbnislieder (1542): “The addition of the singing voice [to the text] results in song, which is the voice of the affections. For just as the spoken word is understood intellectually, it is affectively perceived through song.”[59]

6.4 As Leon Stein points out, in peace dramas music functions as the “handmaiden of pietism and protonationalism.”[60] Sophie Elisabeth’s adoption of Protestant principles regarding music in her settings in the second Zwischenspiele certainly fulfill Stein’s observation. Moreover, they demonstrate her connection to the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft and its aims. While this society was for men only, a kind of honorary membership—called “observer status” by Geck—was made available to certain women who were married to male members of the society.[61] Sophie Elisabeth was granted this membership sometime after 1645; before this date, her Hofmeister, Carl Gustav von Hille, refers to her in correspondence as “Sophie Elisabeth” rather than by the society name she was granted, “Die Befreiende,” the female form of August’s society name.[62] This is not to suggest that Sophie Elisabeth was granted honorary membership to the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft because of her work on Friedens Sieg. Rather, I contend that her text settings in the piece demonstrate that she strove towards the society’s aims to promote an idea of Germanness through the cultivation of the German language by adhering musically to its natural stresses and adopting Protestant principles of music composition. Geck notes that Sophie Elisabeth was particularly proud of her relationship to the society, observing that even though she had the society names “Die Fortbringende” and “Die Gutwillige” in the Académie des Loyales and Tugendliche Gesellschaft, respectively, she chose to put the pseudonym “Die Befreiende” to her work.[63] Her music for Friedens Sieg projects an image of the Wolfenbüttel court as a center for the patriotic Protestantism championed by the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft to the play’s audience of high-ranking guests, who are seen and named in Conrad Buno’s engraving of Cupid’s song in the first Zwischenspiel. In this image of the court, both August and Sophie Elisabeth are depicted as representatives of an ideal of Germanness; this becomes particularly clear in Friedens Sieg’s third act.

6.5 The allegorical figures present in Act 3—particularly Justice, Virtue, Piety, Unity, and Fortitude—stand in stark contrast to those in the first and second acts and in the Zwischenspiele, including Fortuna, Mars, Injustice, Poverty, Famine, and Death, all of whom have been driven away from the stage by the beginning of Act 3 and Peace’s arrival. In the third act it is thus clear that the stage has become a microcosm of an ideal Germany. The act contains seven musical numbers sung by the Muses, almost double the number in the two Zwischenspiele combined. All of them celebrate Peace (Friede) and the cultural, moral, and linguistic regeneration she represents. In addition, unlike the music in the two Zwischenspiele, Sophie Elisabeth’s music in Frieden Sieg’s third act uses a large range of instruments (as illustrated by Conrad Buno’s accompanying engravings), in addition to continuo, to express triumph and celebration.

6.6 The importance of music to the celebration of the victory of peace is made explicit in the final vocal song in Friedens Sieg, “Ofnet die Tühre,” which was performed as Peace’s triumphal procession exited the stage but before the two concluding instrumental dances.[64] Schottelius’s text for “Ofnet die Tühre”—in dactylic tetrameter—draws attention to the function of music here. The first strophe, for instance, reads as follows:

Ofnet die Tühre/ macht weiter die Tohre/

Jauchtzet und singet/ jauchtzet und singet/

Samlet versamlet/ die lieblichen Chore/

Tantzet und springet.(Open the doors, make the gates wider, exult and sing, exult and sing, assemble together the sweet choir, dance and leap.)

Sophie Elisabeth’s homophonic five-part setting (one vocal and four instrumental) emphasizes the musical nature of Schottelius’s text. Here she uses sarabande-like rhythms, the momentum of which, Geck notes, is strengthened by the numerous dotted rhythmic figures (Example 2).[65]

Similar rhythms also appear in the duchess’s setting of “Lobet ihr Schwester,” the opening song of Act 3, which is scored for one singer and five instrumentalists (Example 3).[66] Schottelius’s text for this song is again in dactylic tetrameter and, like that for “Ofnet die Tühre,” refers to the musical nature of praise and celebration:

Lobet ihr Swester/ ja lobet mit Singen/

Lasset die frölige Stimmelein klingen/

Lasset die reineste Seite wol klingen/

Lobet ihr Swester den Herrn mit Singen.(Praise, sister, yes, praise with singing, let the joyful voice ring out, let the purest side ring out! Sister, praise the Lord with singing.)

These two songs, which bookend the third act, play an important role in establishing and affirming its character. The texts of both highlight the centrality of music to the act, and Sophie Elisabeth’s homophonic, dance-like settings emphasize the musicality of Schottelius’s text.

6.7 The procession of Peace (Friede) and the use of music throughout the third act contribute to the consolidation of August’s political power in two ways. Firstly, the grandeur of the spectacle, from the costumes and props to the musical performance itself, was undoubtedly an expensive affair, drawing attention to the court’s and, by extension, August’s intellectual and artistic power. This grandeur is heightened by Sophie Elisabeth’s position as the composer of the Singspiel’s music. Her role was clear to the audience; Schottelius writes in Friedens Sieg that “all musical pieces” were composed by the duchess.[67] Coupled with the characterization of August, both in the Singspiel itself and in its lavish spectacle, Sophie Elisabeth’s compositional skill makes a significant contribution to the overall sense of the ducal couple’s cultural prestige. Secondly, as the third act progresses, it becomes increasingly clear that music is the vehicle for blurring the line between entertainment and reality in Friedens Sieg. The most striking moment of this ambiguity is the performance of the song “Auf ihr Schwester” by the Muses Euterpe, Calliope, Melpomene, and Thalia. This song is performed twice. The first time, the Muses weave garlands made of “the art of peace” and “the favor of heaven,” presenting these first to the heroes on stage, Arminius and Heinrich der Finkler, and then to August, Friedrich Wilhelm of Brandenburg, and Julius Heinrich of Saxony, calling the real-life August a “friend of virtue,” an “enemy of war,” and the “father of peace.”[68] In strophes 6 and 7, the four Muses alternately “[call] upon [the assembled princes] to lead the movement towards the reestablishment of peace,” using the words “flourish,” “blossom,” and “prosper,” and describing the present-day heroes as “resplendent,” “princely,” and “powerful.”[69] Here Sophie Elisabeth uses sarabande and galliarde rhythms,[70] which again emphasize the inherently musical nature of triumph and celebration as they are presented in Friedens Sieg. When the same song is repeated, more peace garlands are presented, this time to Sophie Elisabeth and the other noblewomen present; in this instance, Sophie Elisabeth is called “our princess,” the beautiful embodiment of virtue, and the “mother of the country.”[71] It is clear here that entertainment has spilled over into reality, with this presentation projecting an ideal leadership characterized by the allegorical figures of Peace, Justice, Unity, Virtue, and Piety, and embodied by Duke August and Duchess Sophie Elisabeth.

7. Conclusion

7.1 Schottelius viewed peace dramas as reflections of real life. While in a sense this is true of Friedens Sieg—the Singspiel’s audience is a witness to the horrors of war and the eventual triumph of peace (although peace was not widespread at the time of its first performance)—the reality reflected on stage is somewhat distorted, just as a mirror does not exactly replicate the image in front of it. The Singspiel maintains a patriotic, peaceful stance and places August at the center of this; however, this peaceful patriotism relies on the not-so-peaceful rejection of anything foreign and the idea that Germany must be kept solely for Germans. What Friedens Sieg testifies to, therefore, is an imagined ideal of Germanness and of Germany prevalent among seventeenth-century Protestant intellectuals, which, while only an idea, provides a revelatory lens through which to view the kind of courtly society that was developing at Wolfenbüttel in response to the Thirty Years War.

Acknowledgments

The research for this paper was partly undertaken during my time as a doctoral research fellow at the Herzog August Bibliothek, for which I was supported by the Dr. Günther Findel Foundation. Other stages of the research were generously supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, and a Norman Macgeorge Scholarship.

Figures

Figure 1. Arminius, Heinrich der Finkler, a peasant, and Bolderian. Friedens Sieg, 58.

Figure 2. Seating arrangement at a performance. Friedens Sieg, 1.

Figure 3. The procession of Friede. Friedens Sieg, 148.

Examples

Example 1. “Angst und Qual,” first strophe. Friedens Sieg, 92 (text), 100 (music).

Example 2. “Ofnet die Tühre,” first strophe. Friedens Sieg, 148–50.

Example 3. “Lobet ihr Schwester,” first strophe. Friedens Sieg, 106–7.