The Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music

Items appearing in JSCM may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form and may be shared among individuals for all non-commercial purposes. For a summary of the Journal's open-access license, see the footer to the homepage, https://sscm-jscm.org. Commercial redistribution of an item published in JSCM requires prior, written permission from the Editor-in-Chief, and must include the following information:

This item appeared in the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music (https://sscm-jscm.org/) [volume, no. (year)], under a CC BY-NC-ND license, and it is republished here with permission.

Libraries may archive complete issues or selected articles for public access, in electronic or paper form, so long as no access fee is charged. Exceptions to this requirement must be approved in writing by the Editor-in-Chief of JSCM.

Citations of information published in JSCM should include the paragraph number and the URL. The content of an article in JSCM is stable once it is published (although subsequent communications about it are noted and linked at the end of the original article); therefore, the date of access is optional in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Noel O’Regan, “Asprilio Pacelli, Ludovico da Viadana and the Origins of the Roman Concerto Ecclesiastico,” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 6, no. 1 (2000): par. 4.3, https://sscm-jscm.org/v6/no1/oregan.html.

Copyright © Society for Seventeenth-Century Music.

ISSN: 1089-747X

Volume 2 (1996) No. 1

Passacaglia and Ciaccona: Genre Pairing and Ambiguity from Frescobaldi to Couperin**

Alexander Silbiger*

ABSTRACT

The simultaneous survival of such closely similar genres as the ciaccona and the passacaglia can be best understood by considering them as a genre pair. The distinctions between them are subtle, involving surface features more readily perceptible by ear than by score-based analysis, while the shared features not infrequently give rise to ambiguity between members of the pair. Some composers, notably Girolamo Frescobaldi and François Couperin, seem to have been fond of playing with this ambiguity within a composition, switching back and forth between genre characteristics, or even effecting a gradual metamorphosis from one genre to the other.

1. The Problem of the Passacaglia-Ciaccona Distinction

2. Three Phases in the History of the Passacaglia and the Ciaccona

5. Frescobaldi Redefines the Passacaglia and the Ciaccona

6. Comparison of a Passacaglia and a Ciaccona by Frescobaldi

7. Other Passacaglias and Ciacconas in Frescobaldi's Works

In memory of Tom Walker, the first to shed light on this murky area. His light shall continue to shine.

1. The Problem of the Passacaglia-Ciaccona Distinction

1.1 The search for a universal distinction between the passacaglia and the ciaccona has remained elusive, and many have come to agree with Manfred Bukofzer's conclusion, voiced half a century ago, that "composers often used the terms chaconne and passacaglia indiscriminately and modern attempts to arrive at a clear distinction are arbitrary and historically unfounded." (note 1) But why then did pieces called passacaglia and ciaccona continue to exist side by side through a good part of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with the two designations even appearing in a few instances over consecutive segments of the same piece? (note 2) It seems unlikely that two distinct terms would have been employed almost equally often by the same people, within the same contexts, and over such a long period of time, unless they were considered to have at least subtle differences in meaning. Are there some hidden cues that we have been missing all this time?

1.2 I will argue here that many seventeenth- and eighteenth-century composers did indeed conceive the passacaglia and the ciaccona as different, even if similar. Earlier generations of musicologists mostly failed to recognize those differences because of the prevailing analytical perspectives, which set up the masterworks of the European canon as the measure of all things and which privileged formal macro-structure over surface gesture or affect. A contributing factor may have been that the specific nature of the differences between the two genres was subject to much fluctuation, which is hardly surprising, considering the time span and geographic spread involved; nevertheless, certain aspects of the original distinctions continued to be preserved or revived. But perhaps more important than the particular nature of the distinguishing features was the idea of co-existing sameness and difference associated with the ciaccona/passacaglia pair. The compositional possibilities afforded by their peculiar close relationship may well have been a significant factor in the attraction the pair exerted on certain composers, even if this fascination was not shared by all.

2. Three Phases in the History of the Passacaglia and the Ciaconna

2.1 The earliest reports on the passacaglia and the ciaconna, from around the turn of the seventeenth century, appear mostly in Spanish literary sources, which tell us little about their musical character. (note 3) However, shortly thereafter both began to make appearances as chord strumming formulas in Italian guitar tablatures, and during the 1630s a second phase set in with an outburst of passacaglias and ciaconnas in all types of Italian instrumental and vocal music. Eventually their popularity spread through the rest of Europe, as they displayed a dazzling variety of forms that appears to defy all attempts at generalization. The eighteenth century saw a gradual decline, but there have been occasional revivals in the works of late nineteenth- and twentieth-century composers, which form a third phase in the history of these genres.

3. The post-Bach Phase

3.1 For composers of this third period, Bach no doubt provided the models, first of all with the C-minor passacaglia for organ (BWV 582), and, perhaps to a lesser extent, with the chaconne from the D-minor partita for unaccompanied violin (BWV 1004). Both were seen as varieties of the familiar form of "theme and variations," and the passacaglia specifically as an example of the ground bass variation. The Bach association also provided the genres with a sense of gravity, in line with the nineteenth-century image of that composer, which was further reinforced by his passacaglia's association with the organ.

3.2 Not just composers, but also musicologists formed their conceptions of these genres from the Bach models, as they tended--sometimes still tend--to take their norms from the canonic works of the post-1700 (and mostly German-Austrian) repertory. This is a more problematic habit; strong composers like Bach or Beethoven often profoundly redefined the traditional genres they inherited from their predecessors, and as a consequence earlier examples appear in retrospect to be primitive or immature if not wrong-headed. Compounding the problem for the case of the passacaglia and the ciaccona was the fact that Bach stood near the end of a long tradition and perhaps closer to a tributary than to the mainstream of that tradition.

4. The pre-Frescobaldi Phase

4.1 In the 1960s Tom Walker and another young scholar, Richard Hudson, independently tried to track down the origins of the passacaglia and ciaccona, and this took them far from those solemn and sublime German variation sets. (note 4) They discovered that by the early seventeenth century both genres were well entrenched into the oral traditions of Spanish popular culture, but other than that had little to do with each other. The ciaccona was a rather wild and exuberant dance song imported from the colonies; it frequently provoked censure. The passacaglia was neither a song nor a dance, but a brief instrumental introduction or ritornello--a kind of vamp. Their earliest traces in musical notation are in rasgueado guitar tablatures: brief chord sequences to be strummed back and forth, usually beginning on a tonic chord and ending on a dominant or full cadence. They are presented in those tablatures largely for teaching purposes, and sometimes appear to be little more than exercises for learning to strum standard chord progressions in different keys.

4.2 Richard Hudson attempted to address the differences between the passacaglia and ciaccona by comparing the harmonic bass progressions in these tablatures. (note 5) He found that their progressions form in fact two fairly distinct types; that of the ciaccona, whose formulas often commence with a I-V-VI sequence, is especially well-defined. But when Hudson cast his net wider over the ciaccona and passacaglia repertory, he encountered for each genre a wide range of variants. (note 6) The differences within each type are often as significant as those between them, to the point that the only common denominator for each seems to be the move from I to V. Hudson tried to deal with these variations by constructing elaborate hierarchies of formulas and sub-formulas from which players presumably selected patterns when constructing a passacaglia or a ciaccona, (note 7) but more likely those players simply helped themselves to the various possibilities allowed by the harmonic idiom of the period. The search for a consistent distinction based merely on harmonic bass structures is unlikely to be productive.

5. Frescobaldi Redefines the Passacaglia and the Ciaccona

5.1 Of course, for the players themselves the distinction was not likely to have been an issue as long as the contexts of performance of the two remained different. It is only when passacaglia and ciaccona start appearing together in the written repertory, in the form of fully worked-out compositions scored for various instrumental and vocal combinations, that the question would arise. The first composer to place them side by side in this manner appears to have been Girolamo Frescobaldi, who in his second book of keyboard toccatas of 1627 included both a passacaglia and a ciaccona. (note 8) In his subsequent publications it becomes clear that he enjoyed exploring the possibilities of their relationship--that is, their potential as a genre pair--and also that, in effect, he had redefined these genres for the "high art-music" tradition. (note 9) Thus he initiated the second phase in the history of the passacaglia and the ciaccona, and his conceptions of these genres would leave traces throughout that phase.

5.2 A genre pair is formed by two genres that are similar and in some way associated with each other, and yet remain clearly distinguishable. Straightforward examples from the period are the passamezzo moderno and antico and the pavan and galliard, but the relationship may be more subtle. Generally, the two genres can be identified as members of the pair by a set of shared characteristics, while a set of distinguishing markings serves to tell them apart. When a composer brings together two pre-existing genres to form a pair he usually will accept some of their traditions, but modify others to suit his purposes. A later composer may take over that pair but change the formula a bit; composers are always reinventing genres, and just as much their relationships.

5.3 Genre pairing seems to have held a special fascination for Frescobaldi. He also brought the romanesca and the ruggiero into one another's company, creating pairs for keyboard, solo voice, and instrumental ensemble. (note 10) We shall see that with the passacaglia and the ciaccona he went a step further, but first let us look at how he conceived these two genres and their differences.

5.4 A listener exposed to a number of Frescobaldi's passacaglias and ciacconas will quickly begin to perceive a marked difference between the two genres and before long will be able to identify the type almost as soon as the piece starts--the identification can readily be made without having to hear the whole work to determine its structural scheme. Comparison comes to mind with the Blues: listeners don't have to identify the twelve-bar textbook form to know they are hearing one (indeed, some Blues don't stick to that form, and some pieces that do aren't Blues). Even though, as with the Blues, structural schemes do play a role in the passacaglia and the ciaccona, the immediately audible distinction is conveyed by local and surface features. (note 11)

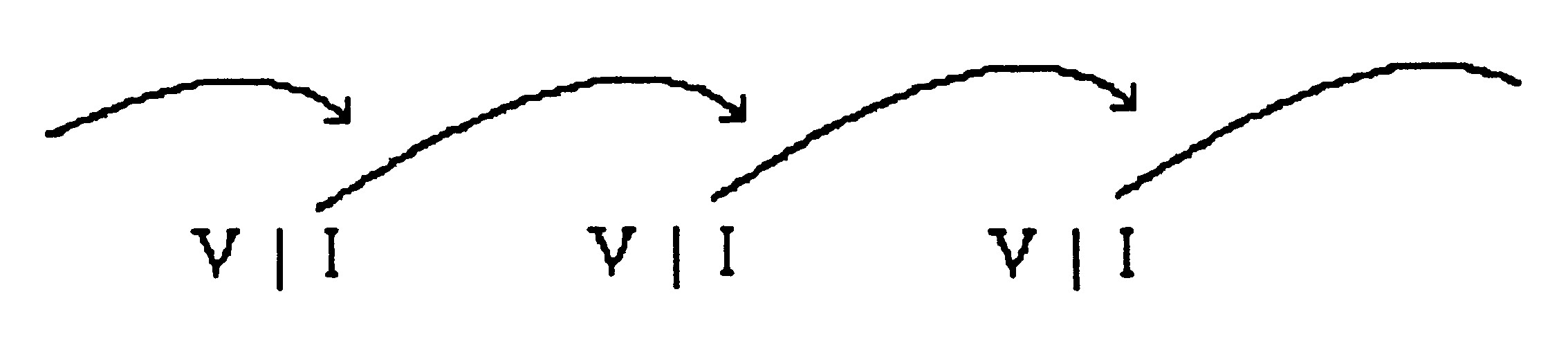

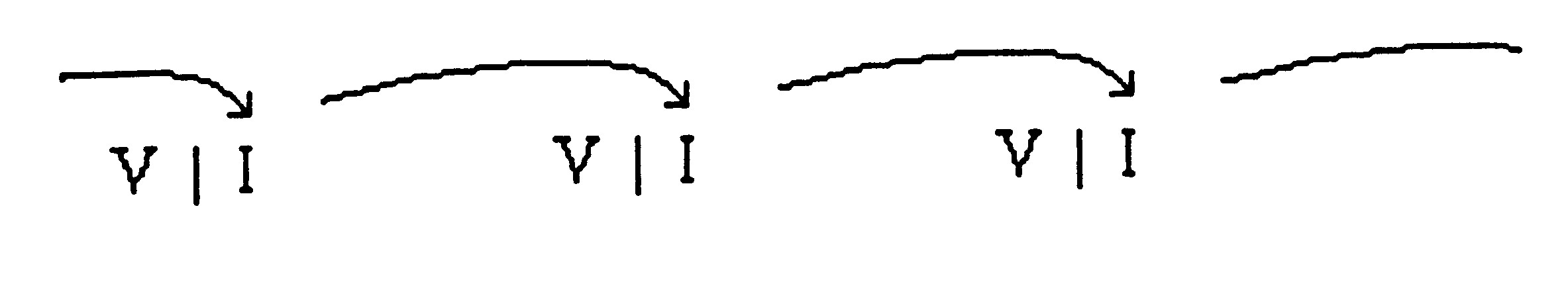

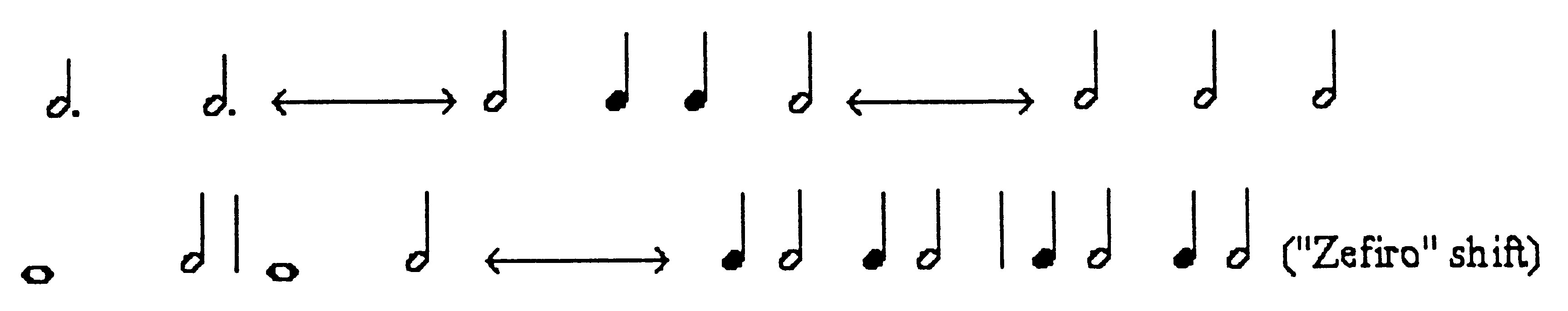

6. Comparison of a Passacaglia and a Ciaccona by Frescobaldi

6.1 To identify some of these features, let us compare a brief representative of each genre (example 1/figure 1/mp3 1 and example 2/figure 2/mp3 2). (note 12) Most of the common elements are obvious, such as a triple beat, a dance character, and a structure composed of brief cycles of equal length, articulated by V-I cadences (see Table 1). (note 13) There is a strong linkage between successive cycles, accomplished by overlapping the end of one and the beginning of the next cycle, or by ending one cycle on a strong beat and commencing the next on the following weak beat (both may be happening in different voices), or sometimes by ending one cycle on the dominant and beginning the next on the tonic. This continuous linking of cycles is the feature that most strikingly sets these genres apart from older cyclic forms of the time like the passamezzo and romanesca variations; probably it is also responsible for their quickly rising and long enduring popularity. It produces an almost irresistible momentum that can sustain such pieces over seemingly endless successions of cycles.

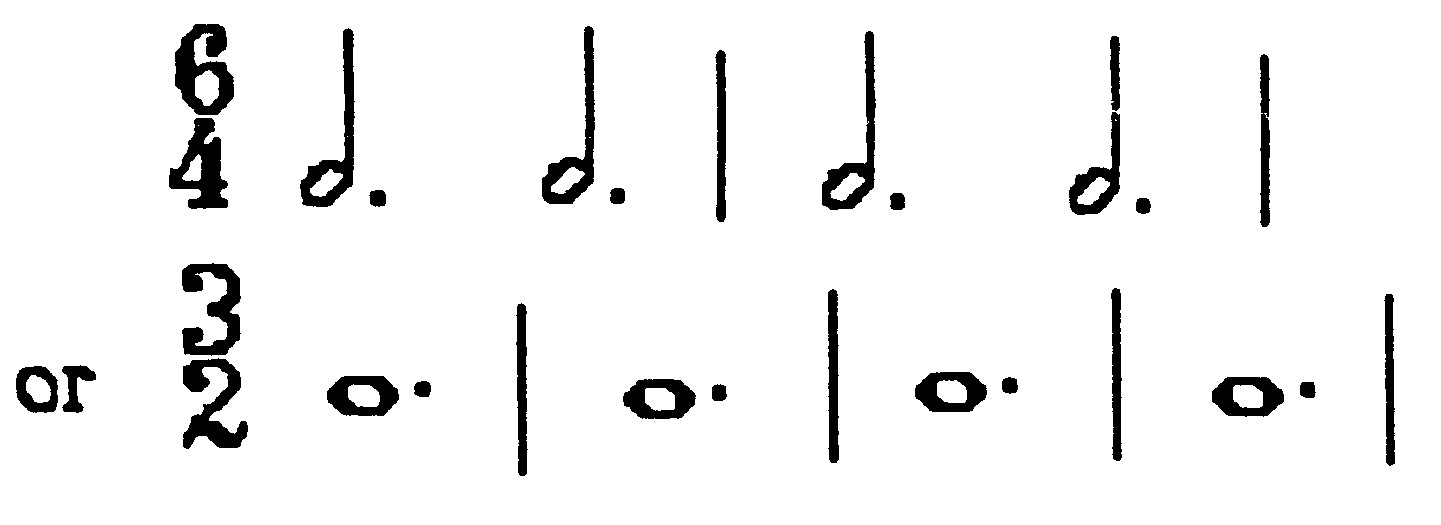

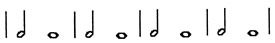

6.2 There is, however, a notable difference in character between the two pieces. The passacaglia has a gentle rocking feeling, perhaps with a touch of melancholy, whereas the ciaccona strides forward in a joyful, up-beat manner. The passacaglia achieves its character by smooth, oscillating melodic motion and, of course, its minor mode, whereas the ciaccona is in major and has strongly directed melodic lines with frequent skips. Meter and rhythm support the character differentiation: the ciaccona gets through a cycle after only two groups of three beats; the passacaglia takes more time to go about its business, not reaching the end of a cycle until after four groups of three beats. Also note that the passacaglia tends to stress the second beat of each group (which momentarily restrains forward motion) and the ciaccona the third beat (which helps it glide along). Finally, the passacaglia has a much higher incidence of dissonances on strong beats than the ciaccona, especially as downbeat suspensions. (note 14)

6.3 What about the overall forms of these pieces: are they ground bass variations or perhaps some other type of "theme and variations"? The bass line of this passacaglia certainly hints at a recurring bass pattern of a descending tetrachord E to B, but the pattern is not foregrounded, as is the ostinato phrase of Bach's organ passacaglia, which is formally introduced as a pedal solo and later made into the subject of a grand closing fugue. In fact, in Frescobaldi's passacaglia the pattern is not rigidly adhered to, and in his longer sets the departures are more radical. The bass of the ciaccona, reminiscent of Monteverdi's well-known "Zefiro" ground, is treated more freely, although certain elements keep recurring. In either piece the sense of a "theme" subjected to variations, is not really present, the way it is, for example, in Bach's violin chaconne.

6.4 Although the two genres may now appear solidly differentiated, the distinction is in fact quite fragile; as little as the shift of a single accent or the change of a single interval may cause a momentary ambiguity. From the quite similar rhythms of the bass lines in the examples it is clear that the generic distinction depends on whether the fourth or fifth quarter-note beat is accented. In much triple-meter music of the period, metric regroupings, either in individual voices or in the entire texture, are an almost constant recurrence, especially near cadences--and in passacaglia and ciaccona, cadences are rarely more than a few beats away. Thus the rhythmic distinction is in constant danger of being subverted. The melodic and harmonic distinctions are hardly more reliable. Raising the second note of the ciaccona bass pattern by a third, as at the beginning of the second cycle, is enough to suggest the passacaglia's descending tetrachord, and chromatic alterations, likely to appear sooner or later in any Frescobaldi composition, may destabilize the major or minor mode. But far from trying to suppress these ambiguities, the composer clearly delights in such genre bending and begins to experiment with how far it can be pushed before the genre begins to lose its identity. Eventually, he will push farther.

7. Other Passacaglias and Ciacconas in Frescobaldi's Works

7.1 Table 2 lists the passacaglias and ciacconas in Frescobaldi's published works. One can observe a clear development in his conception of each genre, from the original pair of 1627, which was withdrawn from a subsequent edition of the volume, through the vocal settings of 1630, which introduced mode and key switching, to the cornucopia of passacaglias and ciacconas in the Aggiunta, the 1637 supplement to the First Book of Toccatas. (note 15) However, tracing that development must remain the subject of another article. (note 16) I do want to note the differences in the texts and their affects in the 1630 settings: in the ceccona for two tenors, the poet with light-hearted pastoral banter tries to seduce a shepherdess to join him, whereas in the passacaglia for soprano he (the persona clearly is male) plays the scorned lover and assumes a bitter, mocking stance.

7.2 The passacaglia and ciaccona occupy a central place in Frescobaldi's Aggiunta, his last publication. Distributed over five sets are a total of one hundred passacaglia and fifty-four ciaccona cycles, among them those shown in examples 1 and 2. By and large the other cycles in the Aggiunta exhibit the characteristics and differences observed earlier for that pair. The minor mode remains the norm for the passacaglia and the major for the ciaccona--as they will continue to do during the further history of the pair--but the possibility of switching the modes is demonstrated right away. (note 17) Note the symmetry in the order of presentation: the E-minor passacaglia is followed by one in B flat major, and the G-major ciaccona by one in A minor. (note 18) The two sets frame the Cento partite sopra passacagli, an extended essay in genre crossing, encompassing several cycles of passacaglias and ciacconas as well as a corrente. (note 19)

7.3 The Cento partite is an astounding composition whose messages we have barely begun to understand. Among other things it is a study in transformations. There are transformations of meter as we pass through a variety of signatures and notational forms; transformations of key (see Table 2); and finally, transformations of genre. Although the beginnings of different genres are marked in the score, most transitions are smoothly accomplished by what one might call genre modulation. Often these will exploit the potential ambiguities of various distinguishing markings to effect a gradual shift.

7.4 A particularly nice move from a passacaglia to a ciaccona is shown in example 3/figure 3/mp3 3. (note 20) At the beginning of the excerpt, which follows a 3/2-6/4 meter shift, the passacaglia character is clear: note the four groups of three quarter-note beats with emphasis on the second beats, the leaning toward C minor and relatively smooth melodic motion. By m. 178 listeners will have little doubt that they are hearing a ciaccona, although they may not be quite sure how they got there. The accent shift from the fourth to the fifth quarter-note beat is firmly established, and similarly the major mode, after much back-and-forth flirtation, is no longer in question. The actual transition marked in the score, at m. 174, passes by almost imperceptibly, although hints of the ciaccona bass were dropped well before that point.

7.5 Each of the transitions is handled slightly differently; example 4/figure 4 show one from a ciaccona to a passacaglia that happens much more abruptly, with simultaneous shifts in key and in note values. (note 21) In m . 148 one still hears a typical ciaccona cycle--note the bass and the metric pattern--but in the next, modulatory cycle the upper voice performs a 4 X 3 pattern, clearly anticipating that of the following passacaglia cycle.

8. After Frescobaldi

8.1 Frescobaldi no doubt based his own formulas and characteristics--if not the idea of pairing--on earlier forms of the genres. Because of his fame and authority, his examples soon drew wider attention to the genres and came to serve as prototypes throughout much of Europe. (note 22) Other composers took over the idea of treating the ciaccona and passacaglia as a pair, juxtaposing examples of each within a collection. The differences these show don't necessarily coincide with those introduced by Frescobaldi and are not always as striking. Nevertheless, almost from the time of Frescobaldi's 1637 publication until at least a century later, several of the distinctions outlined in Table 1 continue to recur in one form or another, both in Italy and elsewhere. I do not claim that all composers who wrote passacaglias or ciacconas during this period were interested in the pairing relationship--or were even aware of it--and several, in fact, seem to have preferred to stick to one term or the other. (note 23) But whenever a composer used both terms in close proximity, my (admittedly provisional) survey suggests that one or more traditional distinctions were operative, whether they be minor/major key contrast, prevalent conjunct/disjunct motion, calmer/livelier tempo or character, (note 24) or contrasting bass formulas similar to those that opened the two Frescobaldi examples. (note 25) Comparative descriptions of the genres in contemporary sources are scarce, but usually mention a minor-major contrast and sometimes also a tempo difference; Brossard in 1703 writes that in the passacaille "the tempo is ordinarily slower than that of the chaconne, the melody more gentle, and the expressions less lively." (note 26)

8.2 Some composers used the ciaccona and the passacaglia as topics (topoi) or employed their bass formulas as signs, sometimes just in passing reference(note 27); see for example Massimo Ossi's fine article on Monteverdi's Zefiro torna and related pieces, Geoffrey Burgess' interesting work on Lully's use of the chaconne, and, of course, Ellen Rosand's classic study on the descending tetrachord as emblem of lament (although it is still not clear to what extent the seventeenth century identified the descending tetrachord ostinato with the passacaglia dance-genre). (note 28) Whether the polarity implied by the pairing has itself been used as a sign is a subject that remains to be studied, but Ossi provides a suggestive example in an aria attributed to Monteverdi, "Voglio di vita uscir," in which the ciaccona bass and the lament bass underline the text in symbolic contrast. (note 29)

9. Germany, France, and Spain

9.1 A few more words about the later non-Italian traditions. The two genres followed rather different courses in Germany and in France. The German organists created a tradition of majestic ground-bass compositions that were given shape and cohesion by increasingly brilliant figurations. (note 30) Although the earliest known example, a pair by the Roman-trained Viennese organist Johann Caspar Kerll (1629-93), uses traditional ground-bass formulas for both his passacaglia and his ciaccona, (note 31) later composers like Pachelbel and Buxtehude introduce formulas of their own devising, and relationships to the genres' origins became increasingly tenuous. (note 32)

9.2 This also would become true to some extent in France, where past mid-century the genres enjoyed unprecedented popularity, both in music for intimate chamber settings and for the public stage, and where characteristically French varieties were created which differed both from the improvisatory and occasionally rambling Italian cycles and the climactic ascents of the German ones, relying instead on orderly and well-balanced structures like the couplet-and-refrain scheme. Lully's grandiose instrumental and vocal production numbers continued to be emulated in the eighteenth century by Rameau and Gluck, and Mozart still includes an orchestral chaconne in the ballet for Idomeneo, which is altogether innocent of the German variation tradition. (note 33)

9.3 We must not fail to mention the traditions of the homeland of these genres; in Spain passacalles and chaconas continued to flourish well into the eighteenth century. Often the passacalles are in duple time, (note 34) suggesting roots that predate the Italian appropriation and redefinition of the genres.

10. Couperin's Contributions

10.1 As a pair, our two genres may have enjoyed their last flowering in the works of François Couperin le Grand, a composer, like Frescobaldi, much interested in the interplay of styles and genres. In the first suite of Les Nations,(note 35) a collection of chamber music from 1726, there is a piece entitled "Chaconne ou Passacaille." (note 36) Did Couperin choose this title to flaunt his indifference to the distinction? But why then did he include in the second and third suites of Les Nations (1726) respectively a passacaille and a chaconne,(note 37) the former suitably in minor and marked noblement, the second in major with a bass strongly reminiscent of the old ciaccona formulas? (note 38) A look at the "Chaconne ou Passacaille" shows that Couperin too may be playing a game of pairs; see example 5. At the beginning, marked "Moderément," a descending bass supports smooth four-bar phrases with suspensions, but the 9th cycle at m. 41 is marked "Vif, et marqué," corresponding to a sudden switch of tempo and character: melodic direction now changes quickly, the phrase is broken in two with a V-I root progression, and the bass begins with the descending fourth that once was the hallmark of the ciaccona. Evidently Couperin had so much fun with his game, and perhaps with the consternation it may have caused, that two years later he decided to play it again in his Pièces de Violes,(note 39) this time with a "Passacaille ou Chaconne"; see example 6. He starts clearly enough in chaconne character: short two-bar phrases and a bass that moves immediately to V, but there is a second section in minor, which commences with a four-bar descending tetrachord. Whether or not my explanation of the title is the right one (at this point it seems as good as any), Couperin's exciting composition is a worthy apotheosis of the two genres, recapturing the high spirits that accompanied them during their early days. Vida vida; vida bona; vida bamanos a chacona!

Return to beginning of article

References

* Alexander Silbiger (LexSilb@acpub.duke.edu) teaches at Duke University. His publications include Italian Manuscript Sources of Seventeenth-Century Keyboard Music, Frescobaldi Studies; and Keyboard Music Before 1700, as well as editions of music of Nicola Vicentino and Matthias Weckmann, and the Garland Series of facsimiles, Seventeenth-Century Keyboard Music. He is currently working on a book on the beginnings and early history of keyboard music notation. Return to text

** An earlier version of this article was presented at the Fourth Annual Conference of the Society for Seventeenth-Century Music at Wellesley College, April 18-21, 1996. The author is working on a larger study of the passacaglia (passacaille) and the ciaccona (chaconne), and welcomes comments and information on the subject. He hopes to incorporate results of this work in his "Chaconne" and "Passacaglia" articles for the revised edition of the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians and in a detailed study of Frescobaldi's Cento partite sopra passacagli. Return to text

1. Manfred Bukofzer, Music in the Baroque Era (New York: Norton, 1947), 42. A classic example of such an attempt--if not ultimately successful--is the wide-ranging and still useful survey by Kurt von Fischer: "Chaconne und Passacaglia: ein Versuch," Revue belge de musicologie, 12 (1958): 18-34. Return to text

2. An example of this, in addition to that of the Frescobaldi's Cento partite discussed below, is a chaconne in La Lande's Mirtil et Mélicerte (1698); the minor section is marked "Passacaille," and the return to major "Chaconne" (ed. in Richard Hudson, The Folia, the Saraband, the Passacaglia, and the Chaconne, 4 vols., Musicological Studies and Documents, 35 [Neuhausen-Stuttgart: American Institute of Musicology, 1982], 4: 119-24). Return to text

3. For the early history of the passacaglia and ciaccona, see Thomas Walker, "Ciaccona and Passacaglia: Remarks on Their Origin and Early History." Journal of the American Musicological Society 21 (1968): 300-320 and Richard Hudson, " Further Remarks on the Passacaglia and Ciaccona." Journal of the American Musicological Society 23 (1970): 302-14. Hudson concerned himself with the two genres in several other important studies; particularly valuable is Hudson's study cited in the previous note, which includes a comprehensive anthology of each, covering their history to the middle of the eighteenth century. I shall refer to items in vol. 3 of that anthology (The Passacaglia) as HP followed by their numbers, and to items in vol. 4 (The Chaconne) as HC, followed by their numbers. Return to text

4. Walker, "Ciaccona and Passacaglia" and Hudson, "Further Remarks." Return to text

5. Hudson, "Further Remarks," especially pp. 310-14. Return to text

6. Example 5 in Hudson, "Further Remarks" shows six forms for the passacaglia, three forms for the ciaccona, and three "neutral" forms which could serve either type (p. 312). Return to text

7. See also Hudson, The Folia, 3: xiv-xxxi and 4: xiv-xxix. Return to text

8. Girolamo Frescobaldi, Il secondo libro di toccate (Rome: Borbone, 1627), 87, 88; mod. ed. in Girolamo Frescobaldi, Opere complete 3: Il secondo libro di toccate, ed. Etienne Darbellay, Monumenti musicali italiani, 5 (Milan: Suvini Zerboni, 1979), 114-19. Return to text

9. By "high art-music tradition" I mean (at least for this period) the tradition in which musical compositions are preserved and disseminated in the form of carefully notated scores. Return to text

10. Respectively in Toccate e partite ... primo libro (Rome: Borbone, 1615), 41, 46; Arie musicali, 2 vols. (Florence: Landini, 1630), 1: 17, 2: 16; and Canzoni da sonare (Rome: Vincenti, 1634), 53, 54. Return to text

11. Whether in the seventeenth century unnotated nuances of performance contributed to the distinction, will have to remain a matter of speculation. Return to text

12. Girolamo Frescobaldi, Toccate d'intavolatura..libro primo (Rome: Borbone, 1637), 70 [example 1/figure 1/mp3 1] and 91 [example 2/figure 2/mp3 2]; mod. ed. in Girolamo Frescobaldi, Opere complete 2: Il primo libro di toccate, ed. Etienne Darbellay, Monumenti musicali italiani, 4 (Milan: Suvini Zerboni, 1977), 89 and 119 respectively. Return to text

13. I shall use "cycle" to refer to an individual variation or unit, and "set" for the entire piece. Return to text

14. Tim Carter drew my attention to the role of these suspensions in avoiding parallels when the bass descends by steps, as in m. 4 of the passacaglia. At the beginning of the ciaccona, where the bass descends by fourths followed by ascents by steps, such suspensions are not necessary, but they appear in m.4, after a descent by step. Clearly there is a close connection between the character of the bass line and that of the contrapuntal texture. Return to text

15. Frescobaldi, Toccate ... libro primo, 69-94. Return to text

16. Such a study might also take account of the passacaglias and ciacconas during the preparatory, pre-publication stages of the Aggiunta, about which thanks to Etienne Darbellay's work we are now fairly well informed; see his Le toccate e i capricci di Girolamo Frescobaldi: Genesi delle edizioni e apparato critico, Girolamo Frescobaldi, Opere complete, suppl. to vols. 2-4 (Milan: Suvini Zerboni, 1988), 56-60 and "Le Cento partite di Frescobaldi: metro, tempo e processo di composizione 1627-37," in Girolamo Frescobaldi nel IV centenario della nascita, eds. Sergio Durante and Dinko Fabris, 359-73 (Florence: Olschki, 1986). Return to text

17. That Frescobaldi regarded the association of the passacaglia with minor and the association of the ciaccona with major as the norm is evident from the way each begins and ends in their appearances in the 1627 and 1630 publications, as well as from their initial appearances in the Cento Partite. Later composers, too, when presenting an example of each in the same context (e.g., publishing them in the same collection), will usually observe this distinction, although not necessarily when one or the other is presented by itself. As with Frescobaldi, this distinction never precluded internal excursions to the other mode, which in France became almost the rule. Return to text

18. In its final version, the B-flat major passacaglia consists of fourteen cycles in B flat followed by five cycles, marked "altro tuono," in G minor; according to Darbellay the G-minor portion was a later addition, and originally formed part of an early version of the Cento Partite; see Darbellay, Le toccate e i capricci, 59. Return to text

19. Frescobaldi, Toccate, 74 and Opere complete, 2: 96 Return to text

20. Frescobaldi, Opere complete, 2: 104-05, mm. 164-82. Return to text

21. Frescobaldi, Opere complete, 2: 103-04, mm. 146-56. Return to text

22. The 1637 editions of the two books of toccatas received unusually wide circulation, and copies still survive in many parts of the world. Return to text

23. Of Bernardo Pasquini, for example, only passacaglias survive among the keyboard works, and of Pachelbel only ciacconas. Instances of a composer's changing the designation when recycling a piece are very rare (and, in any case, could mean that the composer changed his mind about which term was more appropriate rather than that he was indifferent). Georg Muffat reworked a "passacaglio" from a sonata into a "ciacona" for a concerto grosso, but with a meter change from 3/2 to 3/4 (cited in Fischer, "Chaconne," 30), and Gluck renamed a "Passacaille" from Iphigénie en Aulide"Chaconne" when reusing it in Paride et Héléna (Fischer, "Chaconne," 33). Return to text

24. Slower tempo for the passacaglia is sometimes suggested by a meter based on larger note values (e.g., 3/2 rather than 6/4 or 3/4), or higher levels of sub-divisions of the beat (e.g., sixteenth-note divisions rather than eighth-note divisions of a quarter-note beat); for examples of the former, compare HP 59 and HC 84 (Falconiero, 1650), for the latter, HP 67 and HC 93 (Mazzella, 1689). Both the Mazzella pieces are in 3/4, but the passacaglia is marked "largo" at its beginning, whereas the ciaccona is marked "presto"; furthermore, each has subsequent sections crossing over into the opposing tempo, analogous to the mode switching mentioned in n. 17. Return to text

25. For examples, see HP 50 and HC 74 (Piccinini, 1639); HP 59 and HC 84 (Falconiero, 1650); HP 65 and HC 91 (Vitali, c. 1680); HP 66 and HC 92 (Vitali, 1682); HP 67 and HC 93 (Mazzella, 1689); HP 80 and HC 111 (Marais, 1701); HP 85 and HC 118 (Campion, 1731); HP 87 and 119 (Fischer, c. 1738); as well as Bernardo Storace, Selva di varie compositione (Venice, 1664), Johann Caspar Kerll, Modulatia organica (Munich, 1686) [see n. 31 below]; Jean-Baptiste Lully, Acis et Galatée (1687); Nicolas-Antoine Lebègue,Second livre de clavessin (Paris, 1687); Jean-Henry d'Anglebert, Pièces de clavecin (1689); Georg Muffat, Apparatus musico-organisticus (Salzburg, 1690); Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Médée (1694). The scarcity of German examples may in part derive from the fact that most seventeenth-century keyboard music from that region survives in manuscript anthologies rather than in printed, composer-prepared collections. Return to text

26. "...le mouvement en est ordinairement plus grave que celuy de la Chacone, le Chant plus tendre, & les expressions moins vifves;" Sebastien de Brossard, Dictionaire de musique (Paris: Ballard, 1703), s. v. "PASSACAGLIO, veut dire, PASSACAILLE"; see also the English translation by Albion Gruber (Musical Theorists in Translation, vol. 12 [Henryville: Institute of Mediaeval Music, Ltd., 1982], 76). Johann Mattheson, writing somewhat retrospectively (as well as disparagingly) about the "Ciacona, Chaconne, with its brother, or its sister, the Passagaglio, or Passecaille," claims that the passacaglia ought to go faster than the ciaccona ("and not the other way around"), because, he asserts, it is only used for dancing (!), whereas the ciaccona is also used for singing (Der Vollkommene Capellmeister [Hamburg: Herold, 1739; R/Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1954], part 2, chap. 13, sect. 133-135; see also the English translation by Ernest C. Harriss [Studies in Musicology, no. 21; Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1981]). Return to text

27. A nice example of the latter can be heard in Act I, Scene 6 of Monteverdi's L'Incoronazione di Poppea, when Valletto warns Ottavia that Seneca's pompous advice is nothing but songs; as he holds the final syllable of "canzoni," the continuo bass quickly plays twice through the ciaccona bass (in Monteverdi's favorite, "Zefiro" version). Return to text

28. Massimo Ossi, "L'armonia raddoppiata: on Claudio Monteverdi's Zefiro torna, Heinrich Schütz's Es steh Gott auf, and Other Early Seventeenth-Century Ciaccone," Studi musicali 17 (1988): 225-53; Geoffrey Burgess, "Chaconne and Passacaille in the tragédie en musique from Lully to 1750" (unpublished paper); Ellen Rosand, "The Descending Tetrachord: An Emblem of Lament," Musical Quarterly 65 (1979): 346-59. Return to text

29. Ossi, "L'armonia raddoppia, 240-53. Return to text

30. A few modest examples of this format also show up in late seventeenth-century Italy; see for example the Passacallo (1691) by Bartolomeo Laurenti, HP 68. Return to text

31. Johann Caspar Kerll, The Collected Works For Keyboard, ed. David C. Harris (New York: The Broude Trust, 1995), 1: 113, 118. The ciaccona and the passacaglia appear side-by-side in the two principal sources for his keyboard music (see the Critical Report in the Harris edition) as well as in the thematic index of his work appended by the composer to his Modulatia organica ("Subnecto," p. 6). Although the claim that Kerll studied with Frescobaldi is probably without foundation (he would have been only 16 when the older master died), Frescobaldi's pervasive influence on his works is evident. His archetypical pair, the passacaglia in D minor on a descending tetrachord bass, and the ciaccona in C major on a I-V-vi-IV-V formula, may have brought the potential of these two genres to the attention of German keyboard players and, at the same time, provided a model for the characteristic German addition of virtuoso figurations. Return to text

32. On Pachelbel, see n. 23. We cannot tell whether the passacaglia and two ciacconas of Buxtehude preserved in the Andreas Bach Book (BuxWV 159-161)--the only keyboard examples by this composer except for a "ciacona" section in the Prelude in C (BuxWV 137)--had a common origin. The three works are very similar in construction, all three are in minor keys and have four-bar ostinatos with long-short rhythms; however, the passacaglia is written in 3/2 meter suggesting a slower tempo than the 3/4 of the ciacconas; I hear some other differences in character, but whether those are meaningful is difficult to assess with such a small sample. There is little question about the "ciaccona" character of the section in BuxWV 137. Return to text

33. Many earlier German chaconnes and passacailles owed as much to French as to Italian models, as was true of much eighteenth-century German music. Return to text

34. See, for example, HP 75a (Guereau, 1694); HP 81 (Fernandez de Huete, 1702); HP 83a (anon. Spanish, 1707); HP 86a (de Murcia, 1732), as well as several examples by Juan Cabanilles (see his Opera omnia 2, ed. Higinio Anglés [Barcelona: Institut d'estudis Catalans, Biblioteca de Catalunya, Sección de musica, 1933], 43-55). Return to text

35. Les Nations: Sonades et suites de simphonies en trio (Paris: by the author, 1726); mod. ed. in Œuvres complètes, 9, ed. Amédée Gastoué (Paris: Éditions de l'Oiseau-Lyre, 1933), 49. Return to text

36. The title has a precedent in a keyboard piece by Couperin's uncle Louis Couperin, which in the posthumous Bauyn MS is called "Chaconne ou Passacaille," although it appears in its only other (also posthumous) source, the Parville MS, as simply "Passacaille"; see Louis Couperin, Pièces de clavecin, ed. Davitt Moroney (Monaco: Éditions de l'Oiseau-Lyre, 1985), 146-47 and 216-17. It is not clear what Louis meant by the title (if indeed it was his), since his chaconnes are generally quite distinct from his passacailles (including the tendency--not uncommon in France--to use rondeau forms as opposed to variation forms), and this one, unlike the one by François, appears to be a straightforward chaconne. Return to text

37. Œuvres complètes, 9: 123 and 204. Return to text

38. Most of Couperin's other passacailles and chaconnes conform to the traditional opposition, including stately passacailles for harpsichord (in the Huitiéme ordre [1717] and in the Vingt-quatriéme ordre [1730]--the latter one marked "noblement") and light-hearted chaconnes for instrumental ensemble (Troisiéme concert [1722] and Treiziéme concert [1724]--both marked "Chaconne leger"), although his first book of Pièces de clavecin (Paris, 1713) contains an altogether anomalous chaconne in duple time: "La Favorite, chaconne a deux temps." Return to text

39. Pièces de violes avec la basse chifrée (Paris: Boivin, 1728); mod. ed. in Œuvres complètes, 10, ed. Amédée Gastoué (Paris: Éditions de l'Oiseau-Lyre, 1933), 129-39. Return to text

Tables

N.B.: Alternative, pre-formatted views of the following tables are available for users accessing the JSCM with a WWW browser that does not support formatted tables of graphics. Select from Table 1 or Table 2.

Table 1: Frescobaldi's Passacagli and Ciaccone in the 1637 Aggiunta

| Common Elements |

| triple beat | |

| dance character | |

| cyclic structure (cycles marked by V-I cadences) | |

| linking of cycles | |

end of one cycle coincides with beginning of next: |

|

|

|

|

cycle ends on strong beat: |

|

|

|

|

cycle begins on tonic and ends on dominant: |

|

|

|

|

cross-rhythms: |

|

|

|

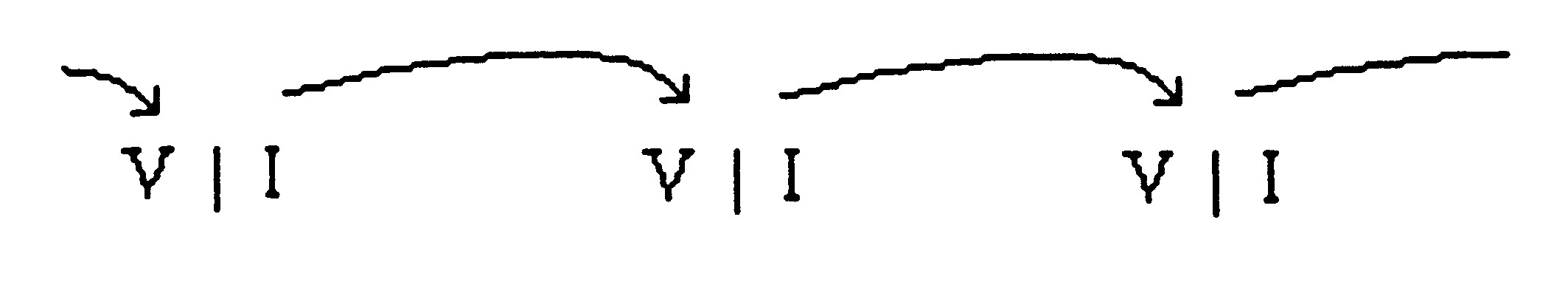

| Contrasting Elements |

| Passacaglia | Ciaconna | |

| rocking, restrained | stepping, lively | |

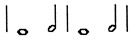

| at beginning of cycle bass moves: | ||

by scale steps |

by descending fourths |

|

| upper voices: | ||

conjunct and oscillating |

disjunct and directed |

|

| minor mode | major mode | |

| frequent dissonances, especially dissonant suspensions on strong beats | fewer dissonances | |

| 4 groups of 3 beats: | 2 groups of 3 (subdivided) beats: | |

|

|

|

| predominant pattern: | ||

|

|

|

Return to paragraph 6.1/paragraph 8.1

Table 2: Passacagli and Ciaccone in the works of Frescobaldi

| Il secondo libro di toccate (1627) | ||||

| Partite sopra CIACCONA | ||||

| 15 cycles: C | ||||

| Partite sopra PASSACAGLI | ||||

| 33 cycles: d | ||||

| Arie musicali (1630) | ||||

| Aria di PASSACAGLIA [a canto solo]: "Così mi disprezzate?" | ||||

| 25 cycles: d - F - d - recitative - G [ciaccona?] - e - recitative - d | ||||

| CECCONA a due tenori: "Deh, vien da me pastorella" | ||||

| 22 cycles: C - G - recitative - G - F - C - recitative - G - C | ||||

| Il primo libro di toccate, Aggiunta (1637) | ||||

| PASSACAGLI (preceded by Balletto and Corrente del Balletto) | ||||

| 6 cycles: e | ||||

| PASSACAGLI (preceded by Balletto and Corrente del Balletto) | ||||

| 19 cycles: B flat - g | ||||

| CENTO PARTITE SOPRA PASSACAGLI | ||||

| 113 cycles: d - corrente - passacagli - F - ciaccona - C/c - passacagli - a - passacagli - ciaccona - d - passacagli - a - e | ||||

| CIACCONA (preceded by Balletto) | ||||

| 8 cycles: G | ||||

| CIACCONA (preceded by Corrente) | ||||

| 8 cycles: a - e - a | ||||

List of Audio Examples

(performed by Andrew Unsworth on a Yamaha TG77 synthesizer at the Duke University Electronic Music Studio)

[Editor's Note, November 22, 2016: While we have converted the original MIDI files to mp3 format, they retain their synthesized sound.]

mp3 1. Girolamo Frescobaldi, Passacagli, Toccate ... primo libro (1637), 70

mp3 2. Girolamo Frescobaldi, Ciaccona, Toccate ... primo libro (1637), 91

mp3 3. Girolamo Frescobaldi, Cento partite sopra passacagli, mm. 164-82, Toccate ... primo libro (1637), 79

List of Music Examples

(set in Finale® by Igor Pecevski)

Example 1. Girolamo Frescobaldi, Passacagli, Toccate ... primo libro (1637), 70

Example 2. Girolamo Frescobaldi, Ciaccona, Toccate ... primo libro (1637), 91

Example 3. Girolamo Frescobaldi, Cento partite sopra passacagli, mm. 164-82, Toccate ... primo libro (1637), 79

Example 4. Girolamo Frescobaldi, Cento partite sopra passacagli, mm. 148-56, Toccate ... primo libro (1637), 79

Example 5. François Couperin, Chaconne ou Passacaille, mm. 1-5 and 41-45, Premier ordre: La Françoise, Les Nations (1726)

Example 6. François Couperin, Passacaille ou Chaconne, mm. 1-4 and 73-76, 1ere Suite, Pièces de violes (1728)